Presence and magnitude of the inguinal nodal metastases are the most important determinants of oncologic outcome in patients with squamous carcinoma of the penis (SCP). Surgical removal of the inguinal lymph nodes provides an important staging and therapeutic benefit to SCP patients, while the methodology of appropriate patient selection for lymph node dissection continues to evolve. Compliant, motivated, and reliable patients with low risk of harboring metastatic inguinal lymph nodes can be managed with careful inguinal surveillance. In SCP patients whose primary tumors demonstrate pathologic features of aggressive disease, modified bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection should be performed and converted to classic ilioinguinal lymph node dissection if metastatic disease is confirmed on frozen sections. Patients with bulky inguinal metastases are unlikely to be cured by surgery alone. Integration of systemic therapy, especially in a presurgical setting, is an attractive strategy for management of patients with advanced SCP, and is currently being studied prospectively.

Presence and magnitude of the inguinal nodal metastases are the most important determinants of oncologic outcome in patients with squamous carcinoma of the penis (SCP). At the initial presentation, clinically palpable inguinal lymphadenopathy is present in up to 60% of patients with SCP, and up to 85% of these patients will be found to harbor metastatic SCP. By contrast, up to 30% of patients with no clinical evidence of enlarged inguinal lymph nodes are found to have occult inguinal micrometastatic disease. Understanding of the unique features of SCP is paramount for thoughtful management of inguinal lymph nodes in patients diagnosed with penile cancer. (1) SCP demonstrates a prolonged locoregional phase, with lymphatic involvement occurring before systemic metastatic progression. (2) Metastatic lymphatic spread of SCP occurs by a predictable and well-characterized anatomic route, initially affecting the superficial inguinal nodal chain, with subsequent dissemination to deep inguinal and pelvic lymph nodes. (3) Unlike many other urologic malignancies, where lymph node dissection provides important staging and prognostic information, in patients with SCP, appropriately performed lymphadenectomy positively impacts the natural history of SCP and has a curative potential in appropriately selected patients. (4) Current clinical staging criteria (physical examination and/or radiologic imaging) are inadequate for accurate detection of micrometastatic nodal involvement and cannot be used to differentiate inflammatory nodal enlargement from metastatic involvement.

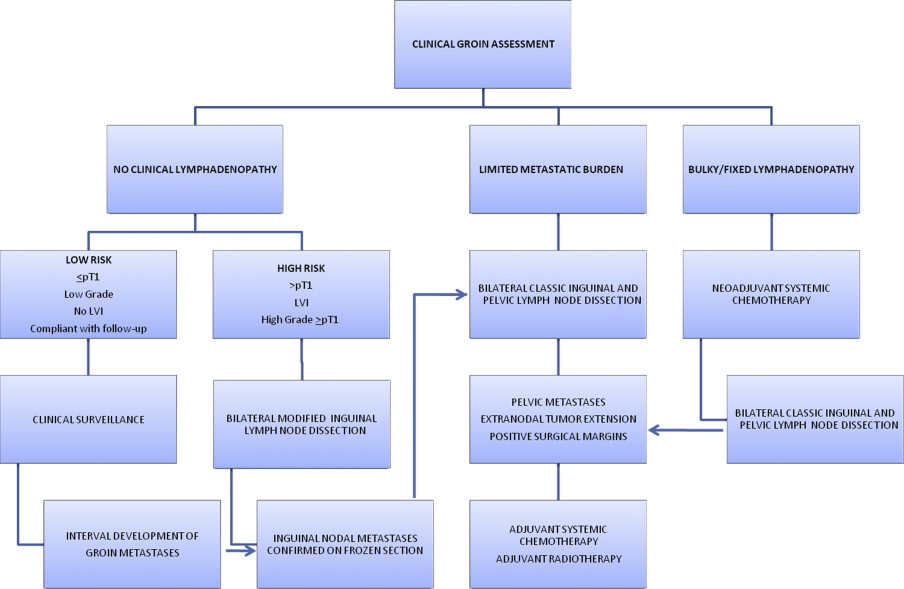

Within this framework, the ensuing discussion focuses on the management of patients with no clinical evidence of regional nodal enlargement at SCP diagnosis, individuals with clinical lymphadenopathy at the time of SCP diagnosis, and patients who develop inguinal lymphadenopathy at an interval after management of the primary lesion ( Fig. 1 ).

Penile lymphatic drainage: anatomic and prognostic considerations

Lymphatic drainage of the penis has been traditionally divided into superficial and deep nodal groups of the inguinal region. The superficial nodes are located under the subcutaneous fascia and above the fascia lata within the femoral triangle. Five anatomic groups of superficial inguinal lymph nodes have been described by Daseler and colleagues: (1) central nodes of the saphenofemoral junction, (2) superolateral nodes of the superficial circumflex vein, (3) superomedial nodes of the superficial external pudendal and superficial epigastric veins, (4) inferolateral nodes of the lateral femoral cutaneous vein, and (5) inferomedial nodes around the greater saphenous vein. The deep nodes lie in the region of the fossa ovalis where the greater saphenous vein drains into the femoral vein through perforating the fascia lata, mainly medial to the femoral vein. The node of Cloquet represents the most cephalad extension of the deep inguinal nodal group. Finally, the lymphatic drainage proceeds cephalad to the external iliac and obturator nodal chains.

Anatomic and clinical observations support orderly and predictable metastatic spread of SCP initially to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes, followed by the deep inguinal nodal group, and subsequently to the pelvic nodal chains. While no “skip” nodal metastases have been reported in the literature, bilateral inguinal nodal dissemination is the rule rather than the exception and has been reported in up to 80% of patients.

Five-year cancer-specific survival decreases from 100% to 90% in node-negative SCP patients to roughly 60% in patients with resected inguinal nodal metastases. Nonetheless, node-positive SCP patients represent a heterogeneous group and survival depends on the number of nodes involved, lymph node density, size of largest nodal deposit, presence of extranodal tumor extension, bilateral groin metastases, and involvement of the pelvic lymph nodes. Cumulative data suggest that patients with minimal nodal involvement (2 or fewer lymph nodes), no evidence of extranodal extension, or pelvic disease derive the most benefit from curative inguinal lymph node dissection, with 5-year cancer-specific survival approaching 80%. This figure decreases to 25% in patients with multiple (>2) lymph nodes involved or presence of extranodal disease, and to less than 10% in patients with pelvic nodal metastases. It is clear that management of ilioinguinal lymph nodes in patients with clinical and pathologic features of advanced nodal disease should be evaluated in the context of a multimodality treatment paradigm, integrating surgical resection with systemic chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy approaches.

No clinical evidence of ilioinguinal lymphadenopathy

Timing of an Intervention

As previously stated, up to 30% of SCP patients with clinically negative groins will harbor micrometastatic disease. It is precisely this group of patients that derives the maximum benefit from surgical removal of their inguinal nodal metastases. Although the morbidity of the inguinal nodal dissection in the modern era has decreased, subjecting all patients with SCP and no clinical evidence of inguinal lymphadenopathy to groin dissections would result in prohibitive rates of overtreatment. There is, however, a growing body of evidence that indicates significantly compromised survival in patients managed with clinical groin surveillance and node dissection at the time of disease progression, compared with patients treated with up-front inguinal lymph node dissection for occult nodal metastases. In a recent report of 40 patients with clinically negative groins after management of primary SCP, the 3-year cancer-specific survival was 84% for patients who underwent immediate lymphadenectomy and were found to have nodal metastases, compared with 35% in those subjected to delayed node dissection ( P = .002). Consequently, a logical approach to management of SCP with clinically negative nodes centers around accurate identification of patients at a high risk of harboring occult inguinal nodal metastases, while sparing the morbidity of inguinal node dissection in patients destined to have pathologically negative nodes. Several strategies designed to address these challenges are currently in practice or are in various stages of clinical development.

Patient Selection for Surgery

Risk stratification based on the primary tumor characteristics is a widely accepted strategy to select patients at high risk of harboring occult inguinal nodal disease for inguinal node dissection. Pathologic primary tumor stage, tumor grade, and presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) have been demonstrated consistently to correlate with the probability of metastatic nodal egress. Patients with primary tumor stage T1 or less, with no evidence of high-grade features or LVI have a less than 10% chance of metastatic nodal disease and are suitable candidates for clinical surveillance. Alternatively, presence of advanced pathologic stage (≥T2), high grade, or LVI are associated with greater than 25% risk of nodal involvement, mandating inguinal lymph node dissection. The current European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines stratify patients into 3 risk groups according to their probability of harboring metastatic lymphadenopathy, based on stage and grade of the primary tumor: low risk: pTis, pTa grade 1 to 2, and pT1 grade 1 tumors; intermediate risk: pT1 grade 2 tumors; high risk: pT2 or higher or grade 3 tumors. EAU guidelines recommend modified inguinal lymph node dissection for patients in intermediate- and high-risk categories (see Fig. 1 ). Recently, Ficarra and colleagues have developed a prognostic nomogram for individualized prediction of metastatic inguinal lymphadenopathy, based on 8 clinical and pathologic variables: tumor thickness, microscopic growth pattern, grade, presence of vascular or lymphatic invasion, tumor infiltration into the corpora cavernosa, corpus spongiosum or the urethra, and the clinical stage of groin lymph nodes. The prognostic accuracy of this model (concordance index 0.876) was superior to that of EAU risk grouping (concordance index 0.697).

The technique of dynamic sentinel node biopsy (DSNB) was developed and adapted for SCP, based on the concept of orderly lymphatic progression of metastatic cells from the primary tumor to the initial draining (sentinel) lymph node. The group at the Netherlands Cancer Institute, which pioneered the use of DSNB for staging of SCP patients, reports cumulative false-negative rate of 5% in 75 patients managed according to their latest DSNB protocol. Patients found to have metastatic involvement of their sentinel lymph node proceed with inguinal lymph node dissection, while patients with benign histology are spared the morbidity of a groin dissection. It should be noted that there is a significant learning curve associated with successful execution of DSNB and that this technique, so far, has been implemented only in a few centers with high volume of SCP patients. Moreover, the low false-negative rate of DSNB reported by the Netherlands Cancer Institute group has not been replicated by other investigators. Pending further standardization and independent validation, DSNB may become the cornerstone strategy for inguinal nodal staging in SCP patients without palpable lymphadenopathy.

Although traditional radiologic imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are unsuitable for detection of micrometastatic nodal involvement, several evolving functional imaging strategies merit further discussion. Tabatabaei and colleagues have recently reported on the utility of a nanoparticle enhanced MRI in a pilot study of 7 SCP patients, in whom they found sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 97% with a positive predictive value of 81.2% for diagnosis of metastatic involvement of the inguinal lymph nodes. Similarly, preliminary experience with 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT in 13 patients with SCP suggested sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 100% for detection of metastatic inguinal lymph nodes. It is clear that further prospective studies designed in the context of clinically node-negative SCP are needed to delineate the role of functional imaging in this setting.

Surgical Technique

Boundaries of classical inguinal lymph node dissection are denoted laterally by the medial edge of sartorius muscle, medially by the lateral edge of adductor muscle, inferiorly by the inferior edge of the fossa ovalis, posteriorly by the muscular floor of the femoral triangle, and superiorly by the inguinal ligament. Regardless of the incision used, skin flaps are developed in the plane just below Scarpa’s fascia, and the areolar tissue is dissected from the external oblique aponeurosis and the spermatic cord to the inferior border of the inguinal ligament, establishing the superior aspect of the nodal packet. The saphenous vein is identified and usually divided at the apex of the femoral triangle; however, in patients with minimal nodal burden, preservation of the saphenous vein may be feasible. The femoral artery and vein are identified at the apex of the femoral triangle (inferior aspect of the nodal packet), and dissected superiorly, controlling small perforators and dividing the saphenous vein if necessary at the saphenofemoral junction. Dissection is minimized lateral to the femoral artery to avoid injury to the femoral nerve and the profunda femoris artery. All of the lymphatic and areolar tissue overlying the femoral vessels and medial to the testicular cord is removed, including the deep inguinal nodes and the node of Cloquet at the femoral canal ( Fig. 2 ). The femoral canal is closed, if necessary, by suturing Poupart’s ligament to Cooper’s ligament, without obstructing the femoral outflow, and the sartorius muscle is mobilized from its origin at the anterior superior iliac spine and transposed medially to cover the femoral vessels ( Fig. 3 ). When pelvic lymph node dissection is indicated, an extraperitoneal approach is used and the common iliac, external iliac, and obturator lymph nodes are removed. When inguinal ligament-sparing incisions are used, care should be taken to completely remove all of the lymphatic tissue in the femoral canal, establishing continuity with the inguinal portion of the procedure.

Modified lymphadenectomy, as proposed by Catalona, has replaced the classic inguinal lymph node dissection as a staging procedure in a setting of clinically negative groins. If nodal metastases are identified on frozen sections after a modified dissection, the procedure is converted to a classic dissection on the affected side. The key points of the modified groin dissection are a shorter skin incision, limitation of the dissection to nodal tissue medial to the femoral artery, preservation of the saphenous vein, and omission of the sartorius transposition ( Fig. 4 ). All of the superficial nodal tissue as well the deep nodes located medial to the femoral vein, including the node of Cloquet, are removed and sent for pathologic examination. There is no proven role for pelvic node dissection in the setting of pathologically benign inguinal nodes. Nonetheless, the authors continue to advocate bilateral pelvic node dissection if metastatic SCP is found in the inguinal regions. Others have advocated pelvic lymph node dissection only if more than one inguinal lymph node is affected or if extranodal tumor extension is present, because the probability of pelvic involvement in these circumstances is 25% or more, compared with 0% to 5% in cases of solitary nodal metastasis. While the debate regarding the necessity and appropriate patient selection for the pelvic lymph node dissection continues, it should be noted that the extraperitoneal pelvic lymph node dissection contributes little to the morbidity beyond that of the inguinal lymph node dissection.

Preliminary experiences with laparoscopic and robot-assisted methods of inguinal node dissection have recently been described, driven by high complication rates associated with standard inguinal lymph node dissection and by overall increasing application of minimally invasive surgical technology in urologic oncology. Theoretical advantages of these minimally invasive surgical approaches include decreased local complication rates, and expedited patient recovery and convalescence. Tobias-Machado and colleagues recently reported comparative experience in 20 and 10 clinically negative groins managed with laparoscopic and open inguinal lymph node dissections, respectively. Mean operative time was 120 minutes for the laparoscopic and 92 minutes for the open procedures. There was no statistical difference in the number of nodes removed. Complications were observed in 70% and 20% of groins managed with open and laparoscopic approaches, respectively. No recurrences have been observed at a median follow-up of 33 months. With further experience, laparoscopic and/or robotic-assisted lymph node dissection undoubtedly will be incorporated into the surgical management armamentarium of SCP patients.

No clinical evidence of ilioinguinal lymphadenopathy

Timing of an Intervention

As previously stated, up to 30% of SCP patients with clinically negative groins will harbor micrometastatic disease. It is precisely this group of patients that derives the maximum benefit from surgical removal of their inguinal nodal metastases. Although the morbidity of the inguinal nodal dissection in the modern era has decreased, subjecting all patients with SCP and no clinical evidence of inguinal lymphadenopathy to groin dissections would result in prohibitive rates of overtreatment. There is, however, a growing body of evidence that indicates significantly compromised survival in patients managed with clinical groin surveillance and node dissection at the time of disease progression, compared with patients treated with up-front inguinal lymph node dissection for occult nodal metastases. In a recent report of 40 patients with clinically negative groins after management of primary SCP, the 3-year cancer-specific survival was 84% for patients who underwent immediate lymphadenectomy and were found to have nodal metastases, compared with 35% in those subjected to delayed node dissection ( P = .002). Consequently, a logical approach to management of SCP with clinically negative nodes centers around accurate identification of patients at a high risk of harboring occult inguinal nodal metastases, while sparing the morbidity of inguinal node dissection in patients destined to have pathologically negative nodes. Several strategies designed to address these challenges are currently in practice or are in various stages of clinical development.

Patient Selection for Surgery

Risk stratification based on the primary tumor characteristics is a widely accepted strategy to select patients at high risk of harboring occult inguinal nodal disease for inguinal node dissection. Pathologic primary tumor stage, tumor grade, and presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) have been demonstrated consistently to correlate with the probability of metastatic nodal egress. Patients with primary tumor stage T1 or less, with no evidence of high-grade features or LVI have a less than 10% chance of metastatic nodal disease and are suitable candidates for clinical surveillance. Alternatively, presence of advanced pathologic stage (≥T2), high grade, or LVI are associated with greater than 25% risk of nodal involvement, mandating inguinal lymph node dissection. The current European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines stratify patients into 3 risk groups according to their probability of harboring metastatic lymphadenopathy, based on stage and grade of the primary tumor: low risk: pTis, pTa grade 1 to 2, and pT1 grade 1 tumors; intermediate risk: pT1 grade 2 tumors; high risk: pT2 or higher or grade 3 tumors. EAU guidelines recommend modified inguinal lymph node dissection for patients in intermediate- and high-risk categories (see Fig. 1 ). Recently, Ficarra and colleagues have developed a prognostic nomogram for individualized prediction of metastatic inguinal lymphadenopathy, based on 8 clinical and pathologic variables: tumor thickness, microscopic growth pattern, grade, presence of vascular or lymphatic invasion, tumor infiltration into the corpora cavernosa, corpus spongiosum or the urethra, and the clinical stage of groin lymph nodes. The prognostic accuracy of this model (concordance index 0.876) was superior to that of EAU risk grouping (concordance index 0.697).

The technique of dynamic sentinel node biopsy (DSNB) was developed and adapted for SCP, based on the concept of orderly lymphatic progression of metastatic cells from the primary tumor to the initial draining (sentinel) lymph node. The group at the Netherlands Cancer Institute, which pioneered the use of DSNB for staging of SCP patients, reports cumulative false-negative rate of 5% in 75 patients managed according to their latest DSNB protocol. Patients found to have metastatic involvement of their sentinel lymph node proceed with inguinal lymph node dissection, while patients with benign histology are spared the morbidity of a groin dissection. It should be noted that there is a significant learning curve associated with successful execution of DSNB and that this technique, so far, has been implemented only in a few centers with high volume of SCP patients. Moreover, the low false-negative rate of DSNB reported by the Netherlands Cancer Institute group has not been replicated by other investigators. Pending further standardization and independent validation, DSNB may become the cornerstone strategy for inguinal nodal staging in SCP patients without palpable lymphadenopathy.

Although traditional radiologic imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are unsuitable for detection of micrometastatic nodal involvement, several evolving functional imaging strategies merit further discussion. Tabatabaei and colleagues have recently reported on the utility of a nanoparticle enhanced MRI in a pilot study of 7 SCP patients, in whom they found sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 97% with a positive predictive value of 81.2% for diagnosis of metastatic involvement of the inguinal lymph nodes. Similarly, preliminary experience with 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT in 13 patients with SCP suggested sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 100% for detection of metastatic inguinal lymph nodes. It is clear that further prospective studies designed in the context of clinically node-negative SCP are needed to delineate the role of functional imaging in this setting.

Surgical Technique

Boundaries of classical inguinal lymph node dissection are denoted laterally by the medial edge of sartorius muscle, medially by the lateral edge of adductor muscle, inferiorly by the inferior edge of the fossa ovalis, posteriorly by the muscular floor of the femoral triangle, and superiorly by the inguinal ligament. Regardless of the incision used, skin flaps are developed in the plane just below Scarpa’s fascia, and the areolar tissue is dissected from the external oblique aponeurosis and the spermatic cord to the inferior border of the inguinal ligament, establishing the superior aspect of the nodal packet. The saphenous vein is identified and usually divided at the apex of the femoral triangle; however, in patients with minimal nodal burden, preservation of the saphenous vein may be feasible. The femoral artery and vein are identified at the apex of the femoral triangle (inferior aspect of the nodal packet), and dissected superiorly, controlling small perforators and dividing the saphenous vein if necessary at the saphenofemoral junction. Dissection is minimized lateral to the femoral artery to avoid injury to the femoral nerve and the profunda femoris artery. All of the lymphatic and areolar tissue overlying the femoral vessels and medial to the testicular cord is removed, including the deep inguinal nodes and the node of Cloquet at the femoral canal ( Fig. 2 ). The femoral canal is closed, if necessary, by suturing Poupart’s ligament to Cooper’s ligament, without obstructing the femoral outflow, and the sartorius muscle is mobilized from its origin at the anterior superior iliac spine and transposed medially to cover the femoral vessels ( Fig. 3 ). When pelvic lymph node dissection is indicated, an extraperitoneal approach is used and the common iliac, external iliac, and obturator lymph nodes are removed. When inguinal ligament-sparing incisions are used, care should be taken to completely remove all of the lymphatic tissue in the femoral canal, establishing continuity with the inguinal portion of the procedure.