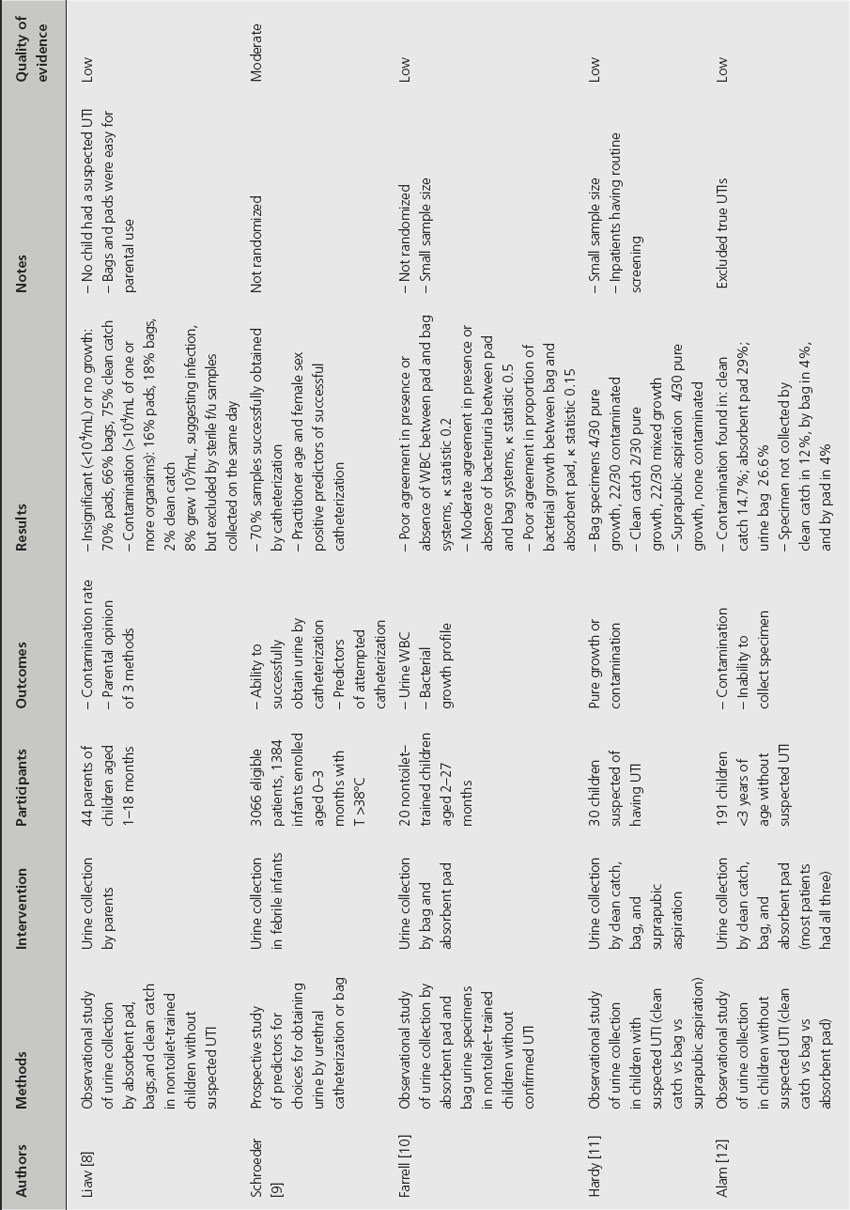

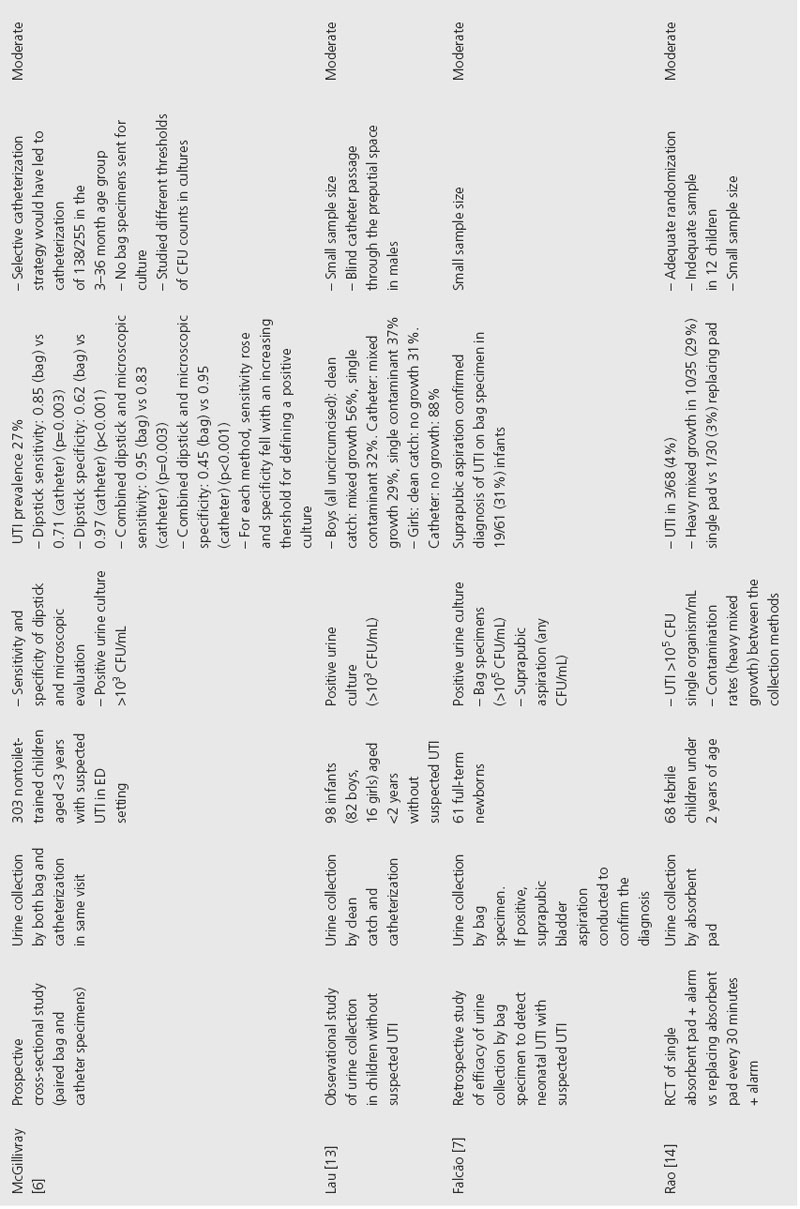

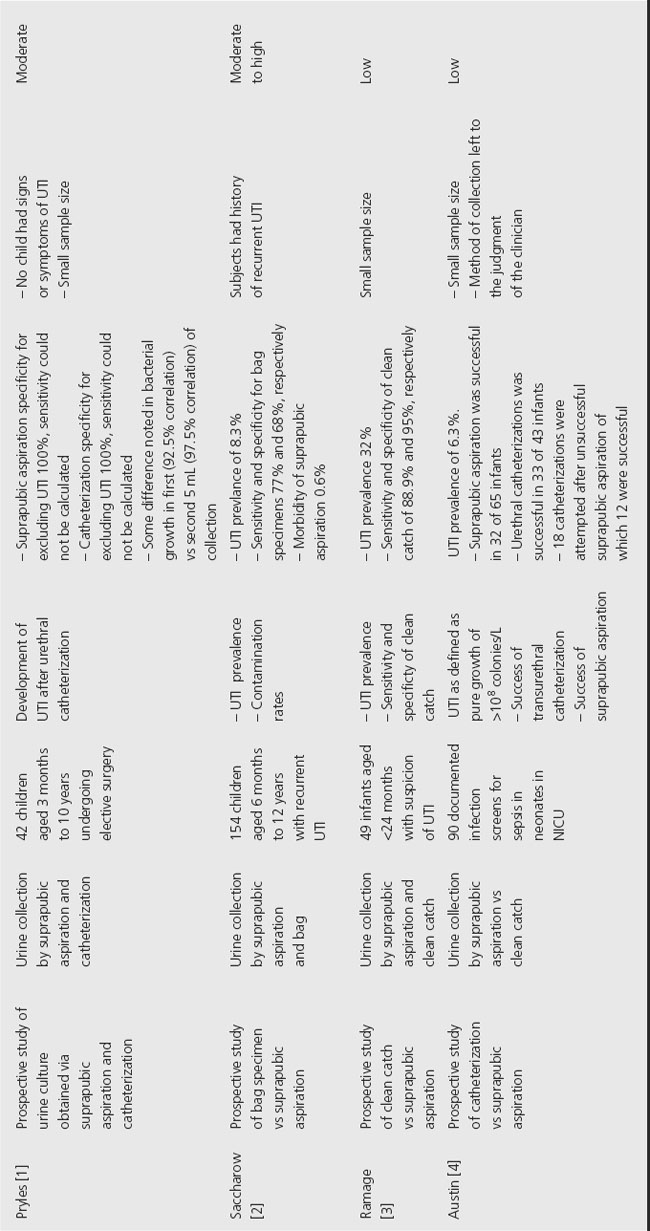

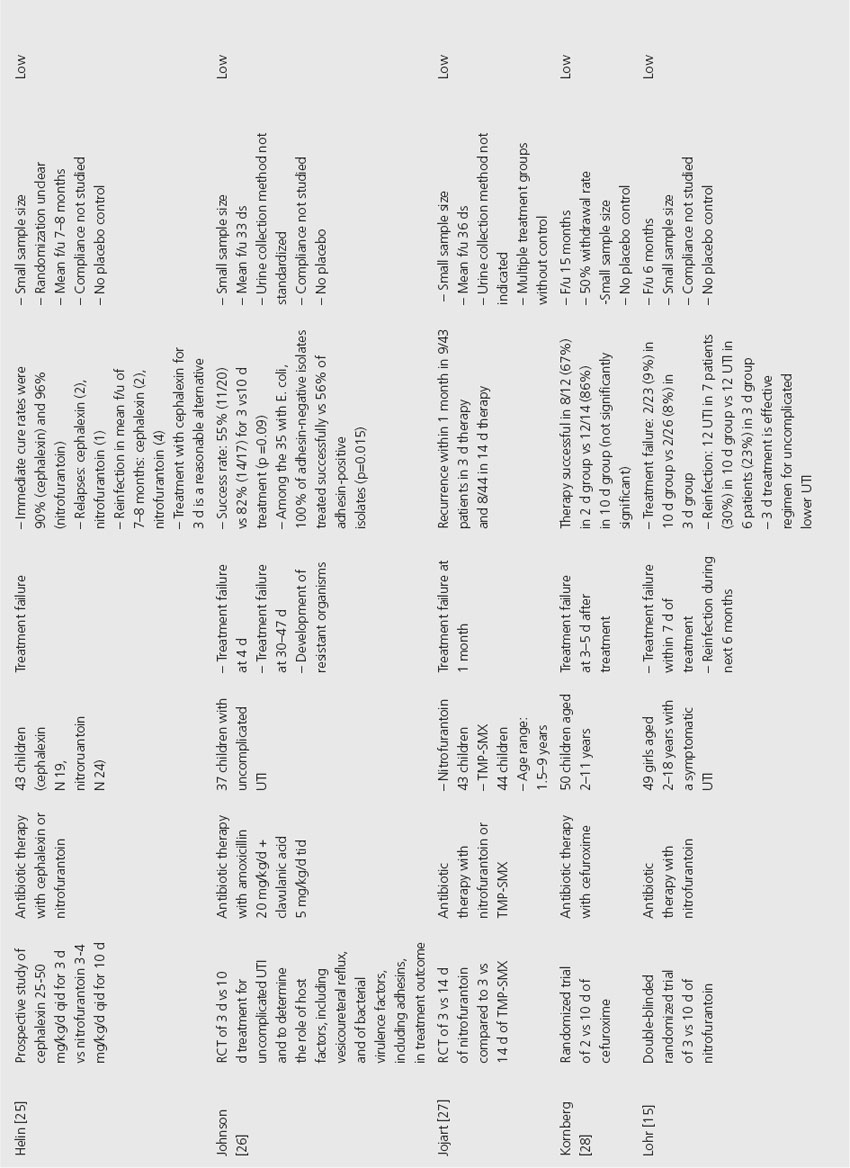

Table 38.1). These studies differ greatly in their design, with collection methods and the age of the cohort being the most variable. Upon examining the data from Pryles et al. [1], suprapubic aspiration approaches 100% specificity for excluding urinary tract infection. In this series, suprapubic aspiration was safe with complications of gross hematuria lasting less than 24 hours in 4/654 and bladder wall hematoma in 1/654, yielding a morbidity rate of 0.6%. Rare cases of bowel perforation and suprapubic abscess have been reported. The specificity of urethral catheterization for the exclusion of UTI approaches 100%. Potential complications include hematuria, catheter-induced UTI, and urethral trauma. Given the few reports documented in the literature, the rate of these complications is considered negligible. Ramage et al. [3] demonstrated that the specificity of clean-catch urine specimens can approach 95% for the diagnosis of UTI in infants. Higher contamination rates are seen in uncircumcised males versus girls. The specificity of bag urine specimen cultures range from 14% to 85% as demonstrated by Saccharow & Pryles [2], McGillivray et al. [6], and Falcão et al. [7]. Given that the sensitivity of a bag urine specimen is 100%, a negative specimen excludes the possibility of UTI.

Table 38.1 Analysis of urine collection techniques to diagnose UTIS

The definition of true infection versus contamination based on bacterial culture colony count remains controversial. The mode of urine collection is the primary factor in defining a significant colony count. The current American Academy of Pediatrics criteria [5] for the diagnosis of UTI in febrile infants and children by urine culture are:

- suprapubic aspiration: the presence of any gram-negative bacilli or more than a few thousand of gram-positive cocci (99% probability of infection)

- urethral catheterization: > 105 colony count (95% probability of infection)

- clean catch:

| male: | > 104 colony-forming units – infection likely |

| female: | 3 specimens ≥ 105 colony count (95% probability) 2 specimens ≥ 105 colony count (90% probability) 1 specimen ≥ 105 colony count (80% probability) 5 × 104 – 105 colony count – if suspicious, repeat 104 – 5 × 104 – if symptomatic, repeat: if asymptomatic, infection unlikely < 104 – infection unlikely |

The clinician must consider other factors before diagnosing a UTI, such as clinical status of the patient, the number of different bacteria species isolated, findings on urinalysis, and the identification of the bacteria isolated.

Comment

We make a strong recommendation that suprapubic bladder aspiration or urethral catheterization be used as the modality of urine collection for the diagnosis of UTI (Grade 1B). They should be considered in critically ill infants who require immediate antimicrobial therapy. These methods can be undertaken with little morbidity, but lack of clinician experience and parental angst may limit their use. In nontoxic-appearing, nontoilet-trained children, specimens obtained by bag collection or absorbent pad have a high contamination rate and should only be considered reliable when negative. If the urinalysis is positive, then urine should be obtained for culture by catheter or aspiration. Clean-catch specimens in toilet-trained children, particularly girls, are also prone to contamination and, likewise, must be interpreted with caution when positive.

Clinical question 38.2

Are there specific antibiotic duration treatment recommendations for acute urinary tract infections in children?

Background

Short-course antibiotic regimens ranging in duration from a single dose to 3 days are common practice in the treatment of uncomplicated UTI in adult women, but this practice has not been applied to the pediatric population. Concerns about renal scarring and pyelonephritis have prompted standard treatment recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics of 7–14 days of antibiotics for UTIs in children, although the optimal duration of treatment remains elusive [5].

Literature earch

A literature search was performed using the US National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health PubMed database. The search terms with imposed limits were as follows: urinary tract infection AND antibiotic AND treatment AND duration NOT reflux NOT neurogenic NOT chronic NOT prophylaxis NOT recurrent NOT abscess NOT bacteruria Limits: Entrez Date from 1920/01/01 to 2008/07/31, Humans, English, All Child: 0–18 years This search yielded a total of 82 articles which were reviewed to determine their relevance to our clinical question. There were 23 articles relevant to our clinical question.

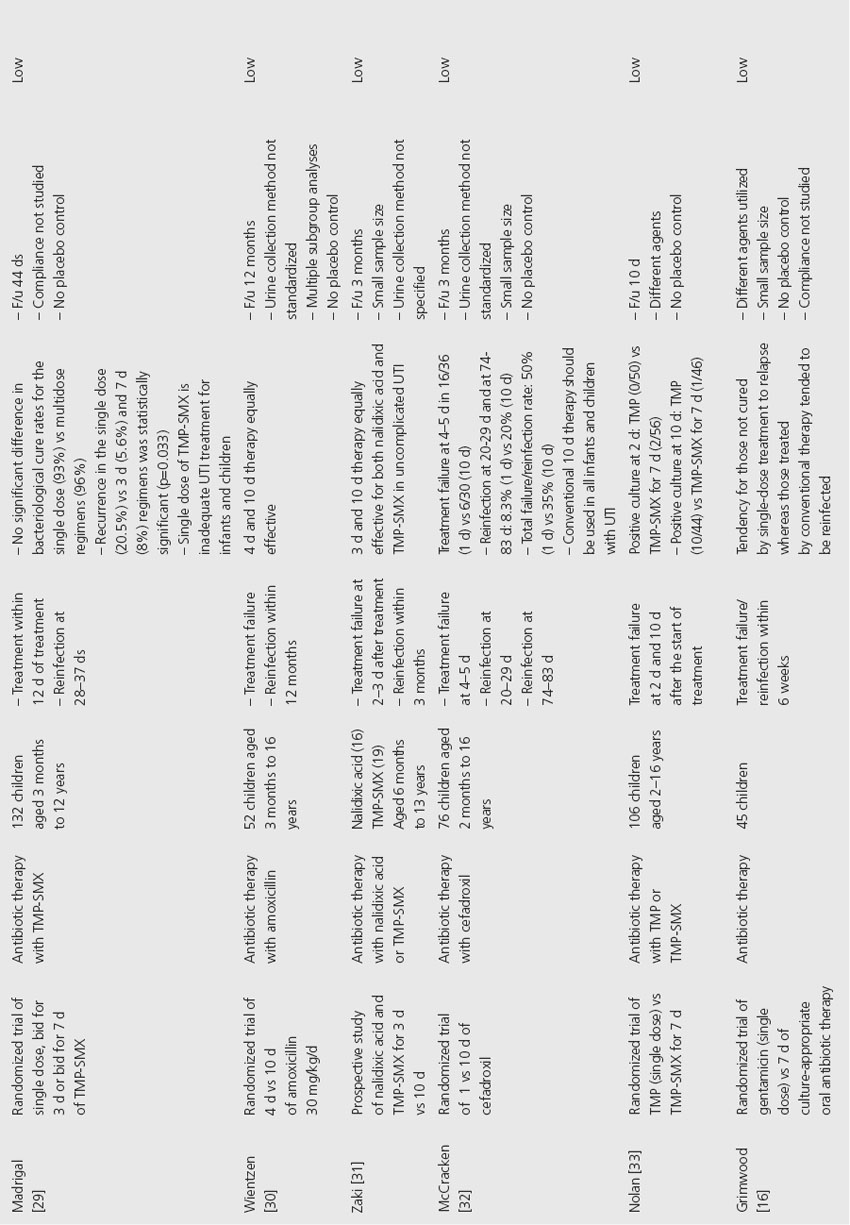

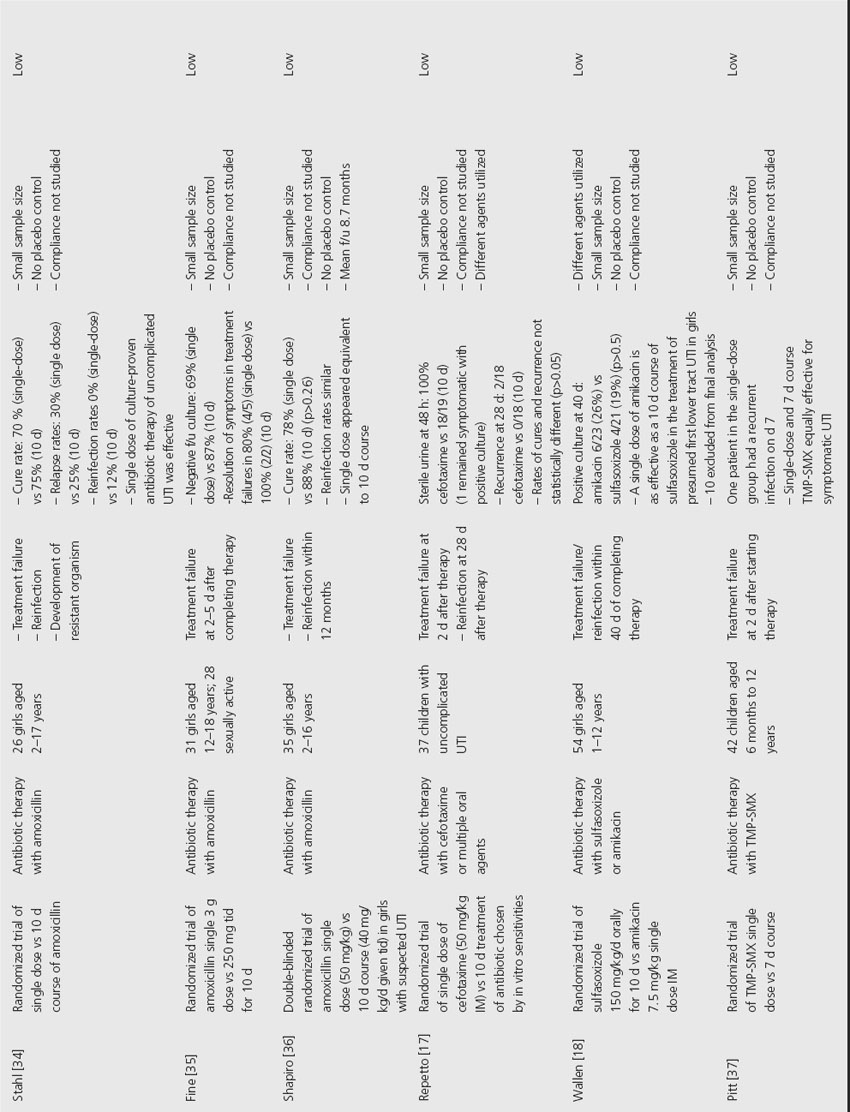

The evidence

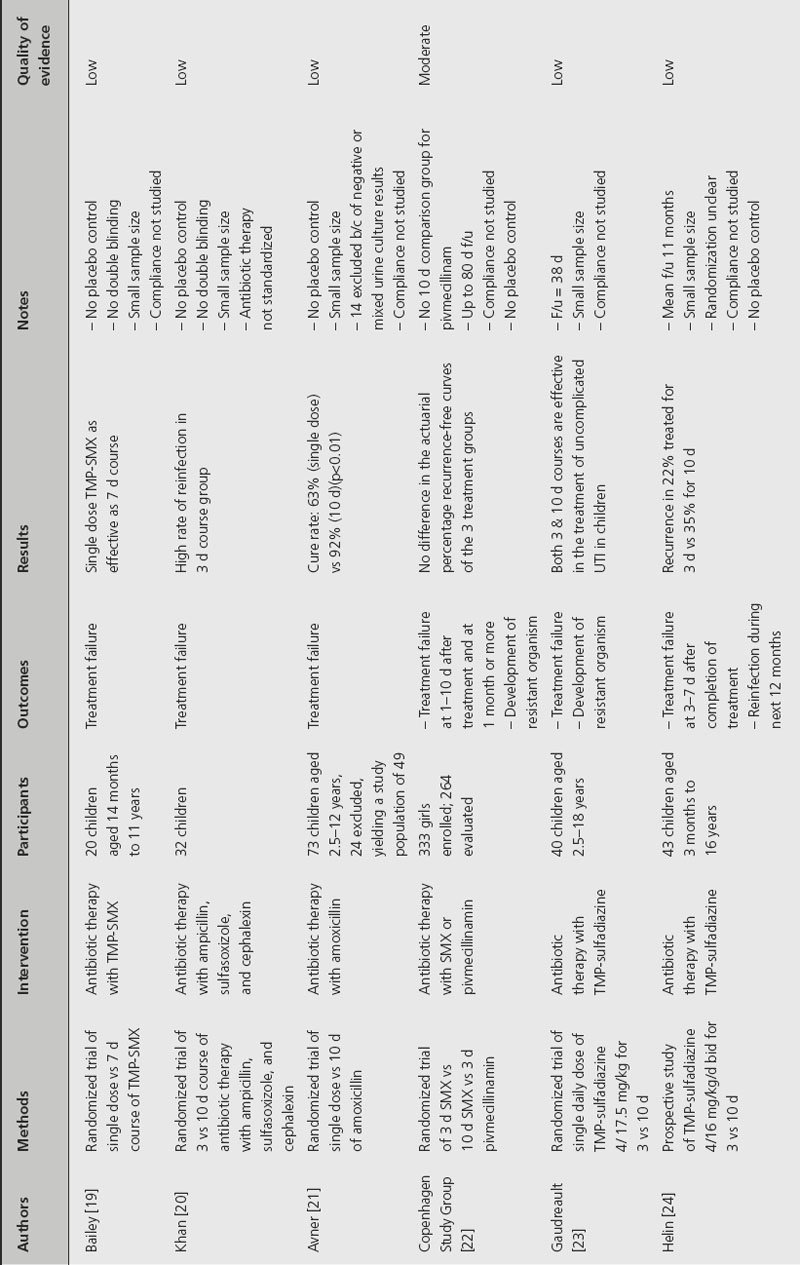

A total of 23 studies have examined the duration of antibiotic therapy for the treatment of acute UTI in children, excluding those which studied children with recurrent UTI (Table 38.2). The overwhelming majority of studies were confounded by poor design. Even considering the randomized controlled trials, the overall quality of the evidence is low. Allocation concealment was adequate in two of the trials while it was inadequate or unclear in the remaining studies. Lohr et al. [15] was the only double-blinded study in the cohort. In three of the studies [16–18], the design precluded blinding as the antimicrobials were administered via different routes. Finally, there is no mention of an intention-to-treat analysis in any of the studies.

Table 38.2 Analysis of antibiotic regimens to treat pediatric UTIs

Overall, the studies were very heterogeneous with regard to cohort age, gender, symptomatology (to differentiate cystitis from pyelonephritis), method of obtaining urine samples, and definition of treatment success. The choice of antibiotic choice and dosage was variable, and confirmation of patient compliance was often lacking. The follow-up periods were also highly variable. The definitions of treatment failure, relapse, and reinfection were not standardized, thus further hampering the ability to draw conclusions regarding adequate treatment.

Comment

In summary, there is no clear evidence available to recommend an optimal agent or duration of antimicrobial therapy for the treatment of pediatric UTI.

Clinical question 38.3

Do prophylactic antibiotics prevent recurrent urinary tract infections in children?

Background

Prophylactic antibiotics have long been a standard therapy for children with recurrent UTIs. However, the evidence supporting such practice is limited. The few reports examining prophylactic antibiotics are confounded by a paucity of controlled studies, variability in the agent used, inclusion of additional nonpharmacological interventions, and variability of host factors in subjects (anatomical anomalies, most specifically vesicoureteral reflux).

Literature search

The literature search was initiated with a review of the Cochrane database and utilization of the noted primary and secondary references. In addition, a PubMed search using the terms “prophylaxis,” “prophylactic antibiotics,” and “urinary tract infections” was conducted with no time frame restriction. Articles were then reviewed to determine which studies involved children (under age 18 years).

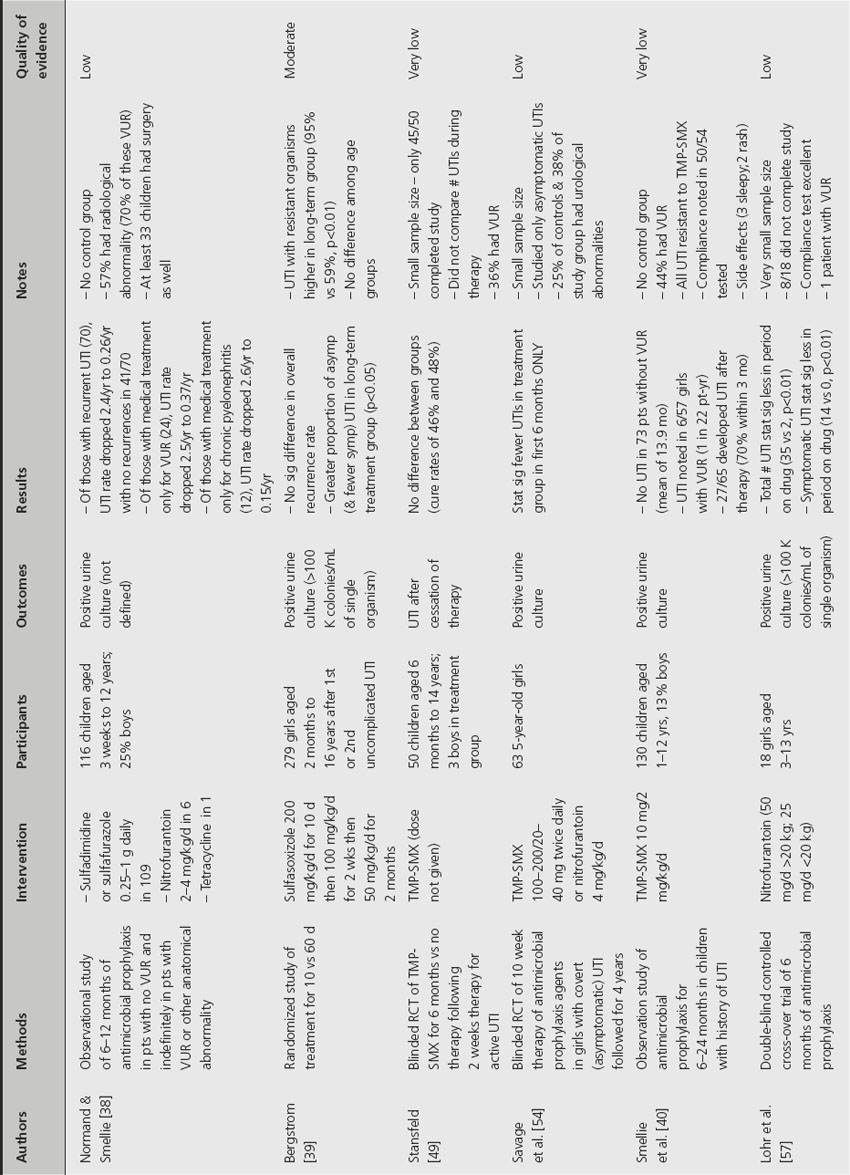

The evidence

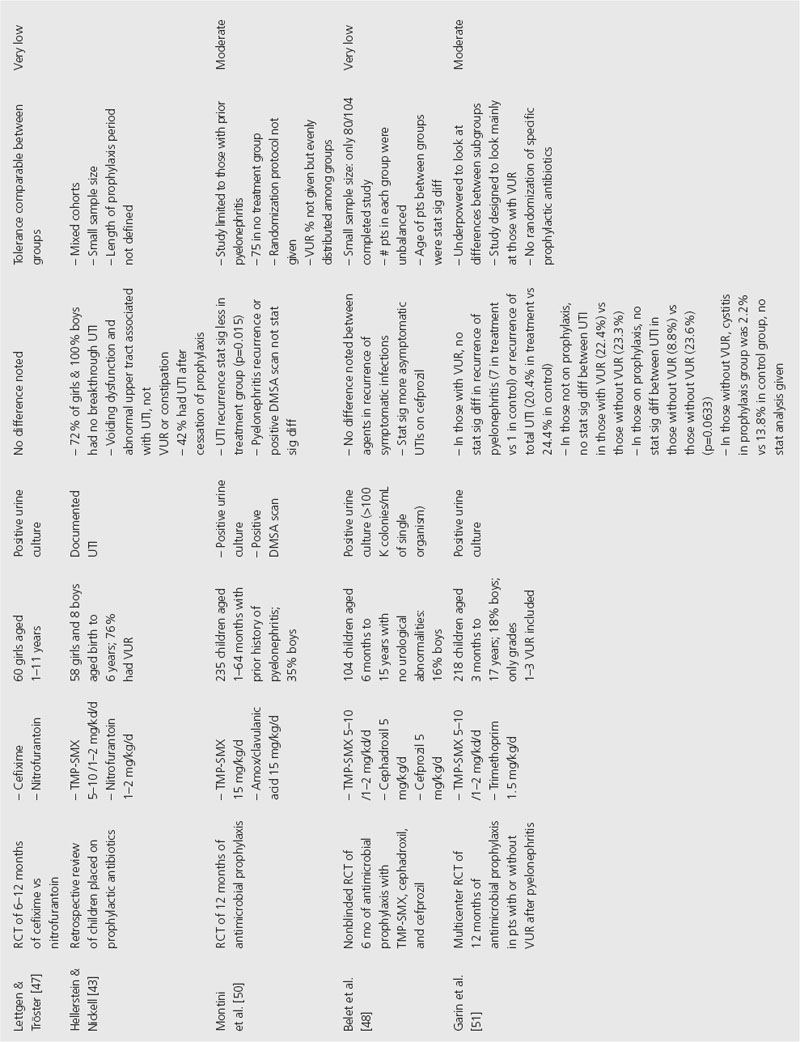

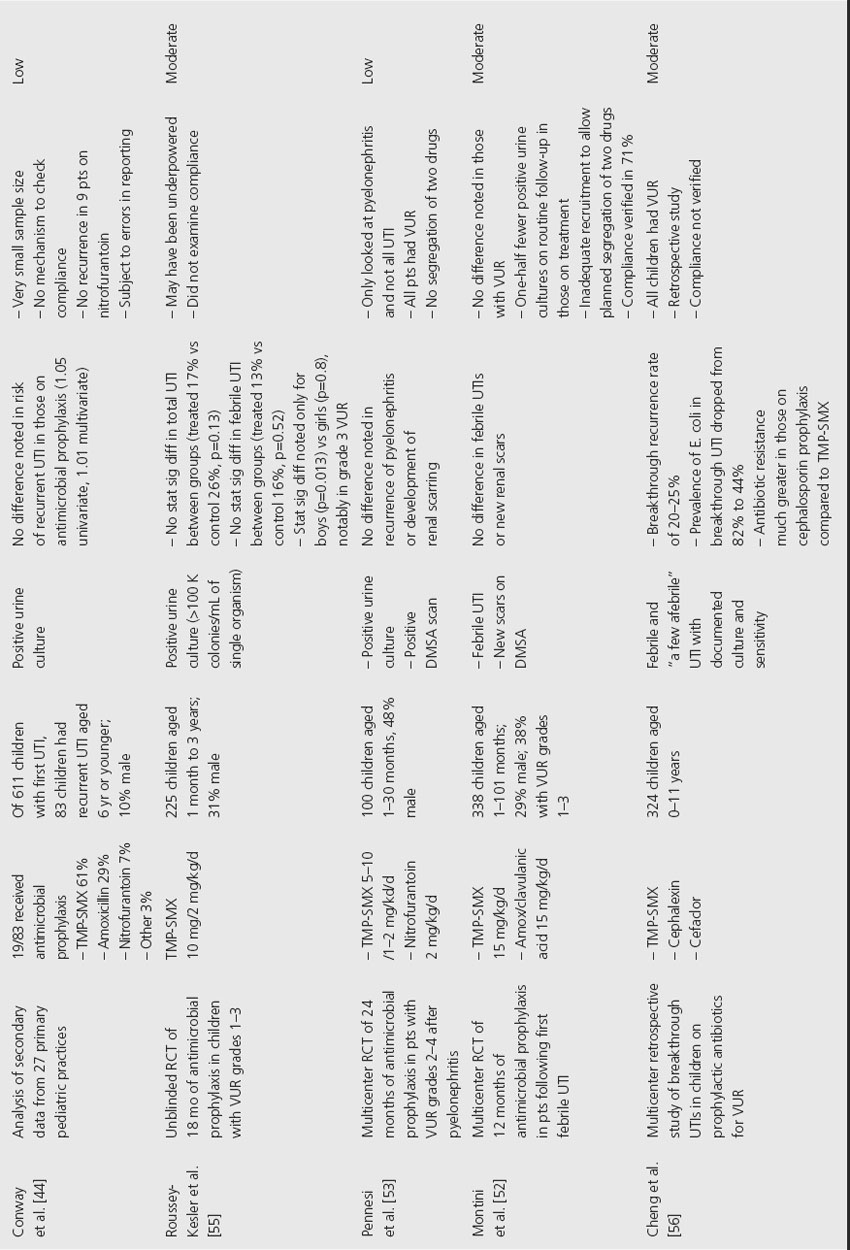

Twenty-one studies have assessed the effect of long-term antibiotic usage to prevent UTIs in children (Table 38.3); however, the studies are very heterogeneous. Although the majority of studies used trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) and/or nitrofurantoin (NF) for prophylaxis, a total of 12 antimicrobial agents were utilized in these 21 studies, and the prophylactic dosages of the antimicrobials were not consistent between studies. Few took measures to assess patient compliance with therapy.

Table 38.3 Analysis of antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent UTIs

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree