HGSC

CCC

EC

MC

LGSC

Genetic risk factors

BRCA1/2

Lynch syndrome

Lynch syndrome

None known

None known

Precursor lesions

Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma

Endometriosis

Endometriosis

Not known

Serous borderline tumor

Molecular abnormalities

P53, BRCA1, BRCA2, HR defectsa

PI3K, ARID1A, MMRb

PTEN, beta-catenin, ARID1A, MMRb

KRAS, HER2

BRAF, KRAS, NRAS

Stage at presentation

III

I

I

I

I–III

Response to platinum chemotherapy

Chemosensitive

Chemoresistant

Chemosensitive

Chemoresistant

Chemoresistant

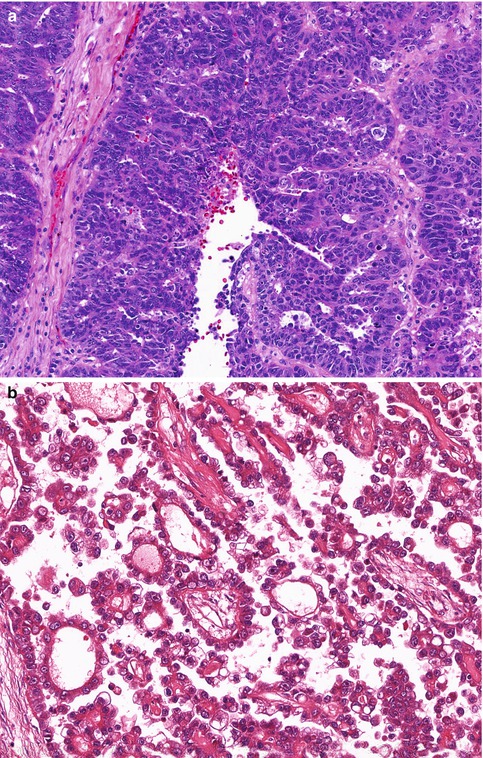

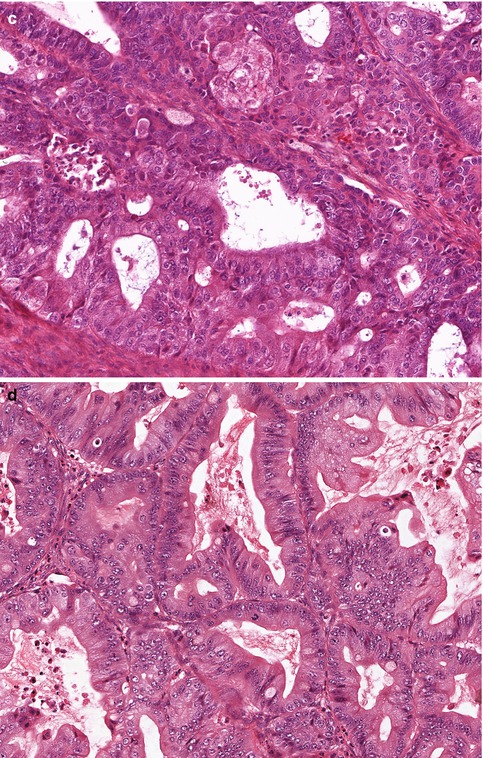

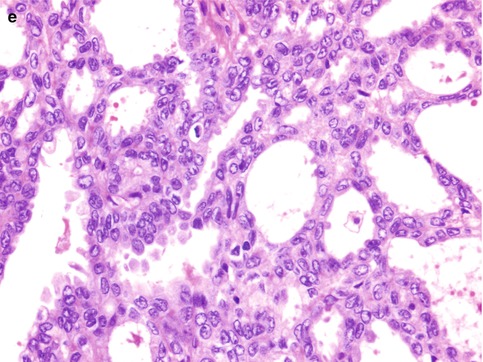

Fig. 25.1

The five subtypes of ovarian surface epithelial-stromal carcinoma. (a) High-grade serous carcinoma, showing stratification and tufting of markedly atypical cells. (b) Clear cell carcinoma, with prominent papillary architecture and cells with clear cytoplasm, (c) Endometrioid carcinoma, showing both glandular architecture and low-grade cytological features. (d) Mucinous carcinoma, with occasional tumor cells showing intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles (goblet cells). (e) Low-grade serous carcinoma, with uniform cells, showing less than threefold variation in nuclear size, and a low mitotic rate

Borderline Tumors

These epithelial neoplasms are characterized by atypia but, unlike the carcinomas, they lack invasion. The same cell types seen in ovarian carcinomas can be encountered as borderline tumors, but serous and mucinous types account for the large majority of borderline tumors. Borderline serous tumors (also referred to as serous tumors of low-malignant potential, or atypical proliferative serous tumors) are characterized by extra-ovarian implants in 20–40 % of cases [8]. If these implants show invasion, the behavior is identical to that of low-grade serous carcinoma. If there is no evidence of invasion in either the ovarian tumor(s) or extra-ovarian implants, a more indolent course can be anticipated, so careful histopathological examination for evidence of invasion is critical in accurate prognostication in these cases. Grossly, serous borderline tumors lack the hemorrhage and necrosis seen in high-grade serous carcinomas, and the papillary structures, whether projecting into cyst cavities or from the ovarian surface, have delicate uniform appearance. Mucinous borderline tumors are invariably stage Ia at presentation, and recurrences are rare. Borderline endometrioid and clear cell tumors are rare, and all reported cases to date have behaved in a benign fashion.

Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors

Adult-type granulosa cell tumors are the most common malignant tumor in this category. Other malignant sex cord-stromal tumors (Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor, fibrosarcoma, sex cord tumor with annular tubules) are very rare. Adult-type granulosa cell tumors, macroscopically, are typically smooth surfaced and confined to the ovary at presentation; on sectioning blood-filled cysts are common. Microscopically they consist of uniform cells with scant cytoplasm, resembling normal granulosa cells. A somatic activating point mutation in the FOXL2 gene is pathognomonic for adult-type granulosa cell tumors [9].

Germ Cell Tumors

More than 98 % of ovarian germ cell tumors are benign cystic teratomas. Malignant germ cell tumors fall into two general categories. The primitive germ cell tumors occur in young women (peak incidence in second and third decades), and can show a variety of histological patterns that are indistinguishable from their more common counterparts in the testis. These are all rare, and include dysgerminoma, yolk sac tumor (endodermal sinus tumor), choriocarcinoma, embryonal carcinoma, and mixed tumors [1]. The second category is malignancies arising in a benign cystic teratoma. These are a result of malignant transformation of one of the components of the teratoma, the peak incidence is in the sixth decade, and squamous cell carcinomas account for more than 90 % of such cases, with occasional cases of intestinal-type adenocarcinoma, thyroid carcinoma, melanoma or other malignancies encountered.

Other Tumors

Metastasis account for most other ovarian tumors, and consideration of any clinical history of prior malignancy is important in cases of unusual ovarian tumors [10]. Ovarian metastases may be the presenting finding, but more commonly are identified at the same time as the primary tumor, or thereafter. An extraordinarily wide range of tumor types, apart from those described previously, may be also be encountered as primary ovarian neoplasms, including tumor types more commonly encountered at other sites, such as lymphoma and melanoma, and rare ovarian tumors of uncertain histogenesis, such as small cell carcinoma of hypercalcemic type.

25.2 Uterine Corpus

Introduction

Cancers of the uterine corpus are predominantly derived from endometrial glandular epithelial cells (endometrial adenocarcinoma), with small number of cases derived from either endometrial stromal cells (endometrial stromal sarcomas) or smooth muscle cells (leiomyosarcomas). In the past, carcinosarcomas, high-grade biphasic tumors of endometrium showing both epithelial and stromal differentiation, were classified with the sarcomas, but based on molecular evidence they are best considered to be endometrial carcinomas with metaplastic (sarcomatous) growth [11].

Carcinomas

Endometrial carcinomas arise through two different pathways, and these are referred to as Type 1 and Type 2 carcinomas [12]. The Type 1 carcinomas account for approximately 90 % of cases and are associated with estrogen excess (obesity, infertility, estrogen producing tumors such as granulosa cell tumor, exogenous hormonal therapy) and the precursor lesion is atypical hyperplasia of the endometrium. Most Type 1 tumors are low-grade (grade 1 or 2) endometrioid carcinomas. Type 2 carcinomas arise in an estrogen independent fashion and the patients tend to be older and not obese, the precursor lesion is endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma, and the prototypical Type 2 tumor is serous carcinoma of the endometrium. It is now clear that these Type 1 and Type 2 designations, which were derived based on consideration of epidemiological data, refer to loose clinicopathological clusters and do not correspond to specific histopathological tumor types. As can be seen from Fig. 25.2, some serous carcinomas arise from low-grade endometrioid carcinomas, in patients with increased estrogenic stimulation of the endometrium, as a result of acquired mutations during tumor progression, while some arise de novo, from endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma, in a background of atrophic endometrium [13]. Gross Findings: Endometrial carcinomas present as exophytic masses projecting into the endometrial cavity. When large, they may prolapse through the cervical os. The tumor is typically friable and soft, and there may be extensive necrosis. Myometrial invasion, cervical involvement, serosal implants or extrauterine spread may be seen, and are more common in high-grade endometrial carcinomas. Microscopic Findings: Endometrial carcinomas, like other ovarian carcinomas, are subclassified based on cell type. Endometrioid, serous, and clear cell subtypes, and carcinosarcomas together account for almost all cases of endometrial carcinoma. Endometrioid carcinomas are composed of glandular epithelial cells resembling normal endometrial epithelium, but with significant nuclear atypia and increased mitotic activity. Squamous differentiation and mucinous metaplasia are common. Endometrioid carcinomas are graded based on the percent solid non-squamous growth as grade 1 (<5 % solid), grade 2 (6–50 % solid), or grade 3 (>50 % solid) [14]. Grade 1 and 2 tumors are considered low grade, account for most endometrioid carcinomas, and a majority are stage Ia at presentation. All serous carcinomas, clear cell carcinomas, and carcinosarcomas of the endometrium are considered high-grade [1]. Serous and clear cell carcinomas resemble their counterparts in the ovary, and most commonly show papillary or solid architecture, although glandular architecture is also commonly encountered. The tumor cell nuclei show high-grade features and there is a brisk mitotic rate. Carcinosarcomas have both a high-grade carcinoma and high-grade sarcoma component; the sarcoma can be homologous (i.e. composed of cell types normally found in the uterus, such as smooth muscle or endometrial stromal cells) or heterologous (e.g. malignant cartilage, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue etc.).

Fig. 25.2

While most endometrial carcinomas can be fit into either the Type 1 or Type 2 category (shown on the left and right, respectively), a significant number of cases fall somewhere in the middle, and based on clinical, pathological and/or genetic features are intermediate between typical Type 1 and Type 2 endometrial carcinomas (From McConechy et al. [13])

Sarcomas

Within the category of uterine sarcoma, there are (1) leiomyosarcomas, of smooth muscle origin, (2) endometrial stromal sarcomas, of endometrial stromal cell origin, and (3) high-grade undifferentiated sarcomas, which probably are a mixed group of cases, including poorly differentiated leiomyosarcomas and endometrial stromal sarcomas, in which morphological features of smooth muscle or endometrial stromal cell origin, respectively, have been lost, and poorly differentiated carcinosarcomas in which the carcinomatous component has been overgrown. Leiomyo-sarcomas show complex genetic abnormalities, and once cases of benign mimics of leiomyosarcoma are excluded (e.g. mitotically active leiomyoma, leiomyoma with bizarre nuclei, etc.) are aggressive neoplasms [15]. They consist of fascicles or bundles of spindle cells with markedly atypical nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm, that stain positively for markers of smooth muscle differentiation, such as desmin and h-caldesmon. There is no one feature that allows distinction between leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas, apart from metastasis, and a combination of infiltrative margin, mitotic activity, cytological atypia, and coagulative tumor cell necrosis are used in the diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma [16]. Rare tumors have morphological features intermediate between leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, and a designation of “smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential” (STUMP) can be used for those cases. Endometrial stromal sarcomas, unlike leiomyosarcomas, are characterized genetically by recurrent translocations. In low-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas the chromosomal translocation t7:17, bringing together the JAZF1 and SUZ12 genes, is the most common genetic abnormality in low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma [17], while high-grade stromal sarcomas are characterized by t10:17 translocations [18]. Endometrial stromal sarcomas are characterized by cells with scant cytoplasm, and prominent small blood vessels, resembling the spiral arterioles of the normal endometrium. Mitotic figures are present, being more common in the high-grade endometrial stromal sarcomas. The high-grade undifferentiated sarcomas consist of pleomorphic cells which often show differentiation along heterologous lineages, such as cartilage or skeletal muscle. Mitotic rates are high, and abnormal mitotic figures common.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree