Background

The classification and grading of papillary urothelial neoplasms have been a long-standing source of controversy (

5). There are numerous grading systems, most of which have poor interobserver reproducibility, with most cases falling into an intermediate category (

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13). The most commonly used grading systems for bladder tumors have been those proposed by the WHO. In 1973, the WHO system proposed that tumors be categorized into benign urothelial papillomas and three grades of carcinoma (grades 1, 2, and 3) (

8). A major limitation of the WHO (1973) grading system was its vague definition of the various grades and its lack of specific histologic criteria. The following statement is the sole description of the difference among WHO grades 1, 2, and 3 as written in the original WHO (1973) system: “Grade 1 tumors have the least degree of anaplasia compatible with the diagnosis of malignancy. Grade 3 applies to tumors with the most severe degrees of cellular anaplasia, and Grade 2 lies in between.” In December 1998, members of WHO and ISUP published the WHO/ISUP consensus classification of urothelial (transitional cell) neoplasms of the urinary bladder (

1). This new classification system arose out of the need to develop a more detailed classification system for bladder neoplasia and because many of the tumors classified as “transitional cell carcinoma, grade 1” had no potential for malignant behavior once completely excised. In 2004, WHO revised its classification of urothelial tumors, adopting the WHO/ISUP system, resulting in a unified grading system for urothelial tumors (

14). Because these systems are identical, in this text, the grading system is referred to as the WHO/ISUP system.

WHO/ISUP System

The WHO/ISUP system is a modified version of the scheme proposed by Malmström et al. (

11) One of the major contributions of the WHO/ISUP system is a detailed histologic description of the various grades, using specific cytologic and architectural criteria. These criteria are based on

the architectural features relating to the histology of the papillae and the overall organization of the cells. Cytologic features encompassed in the WHO/ISUP system include nuclear size, nuclear shape, chromatin content, nucleoli, mitoses, and umbrella cells. Papillary tumors may show heterogeneity of grade. Tumors are graded based on the highest grade exhibited, although it remains to be defined what percentage is minimally needed to place tumors in a higher category when the highest grade is focal (see “

High grade papillary carcinoma”). The terminology used in the WHO/ISUP system for carcinomas is consistent with that used in urine cytology.

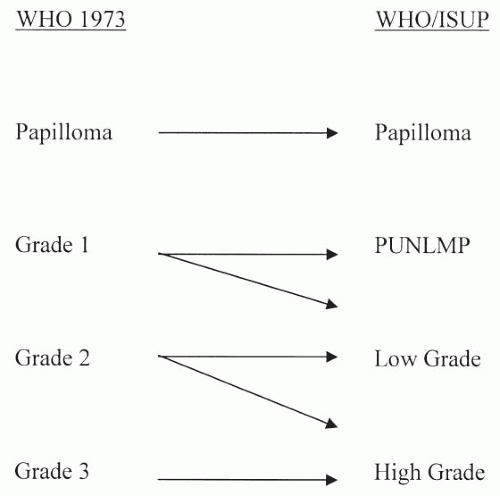

Relation of WHO (1973) to WHO/ISUP

A major misconception in the application of the WHO/ISUP classification is that there is a one-to-one translation between it and the WHO (1973) classification system (

Fig. 3.8). Only at the extremes of grades in the WHO (1973) classification does this one-to-one correlation hold true. Lesions called papilloma in the WHO (1973) classification system are also called papilloma in the WHO/ISUP system. At the other end of the grading extreme, lesions called WHO (1973) grade 3 are, by definition, high-grade carcinoma in the WHO/ISUP system. However, for WHO (1973) grades 1 and 2, there is no direct translation to WHO/ISUP classification system. Rather, lesions must be analyzed using the criteria of the WHO/ISUP classification system without regard to how they were diagnosed in WHO (1973) system. Lesions formerly called WHO (1973) grade 1, which upon review show no cytologic atypia and merely thickened urothelium with, at most, nuclear enlargement, would be called

papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential (PUNLMP). However, other WHO (1973) grade 1 lesions with definite yet slight cytologic atypia would be diagnosed in the WHO/ISUP system as low-grade urothelial carcinomas.

Within the WHO (1973) system, grade 2 is a very broad category. It includes lesions that are relatively bland, which, in some places, are diagnosed as WHO (1973) grade 1-2; these lesions in the WHO/ISUP system would be called papillary urothelial low-grade carcinoma. In other cases, WHO (1973) grade 2 lesions border on higher grade lesions and, in many institutions, are called WHO (1973) grade 2-3; these lesions in the WHO/ISUP classification system would be called high-grade carcinoma. In the old WHO (1973) system, a large percentage of patients with noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinomas were called grade 2, an ambiguous group that the urologists did not know how to treat. In the WHO/ISUP grading system, these grade 2 tumors can be segregated roughly equally into low- and high-grade cancers with correspondingly low and high risks of progression (

15,

16,

17). When WHO (1973) grade 2 tumors are reclassified as high-grade tumors, they show molecular aberrations usually associated with cancers of higher grade and poor outcome, further supporting that WHO (1973) grade 2 tumors form a heterogeneous group that can be subdivided into low- and high-grade cancers (

18).

There have been several studies comparing WHO (1973) and the current WHO/ISUP system. Most have demonstrated a superiority of WHO/ISUP in predicting recurrence and progression or interobserver reproducibility (

15,

19,

20,

21,

22). Whether routine ancillary studies such as immunohistochemical or molecular markers will aid us in better stratifying these tumors into distinct risk groups remains to be proven.

Others have reported no difference in interobserver reproducibility of WHO/ISUP compared to WHO (1973), although in some of these works, the WHO/ISUP grade was merely translated from the WHO (1973) grade, which, as described earlier, is inaccurate (

23,

24,

25). In another study comparing the two grading systems, there was no difference in survival, yet one would not expect a difference in survival as the vast majority of papillary urothelial neoplasms do not result in the death of the patient; the more appropriate endpoints to evaluate are progression (in grade or stage) and recurrence (

26).

Papilloma

Using the WHO (1973) system, some experts applied very restrictive criteria for the diagnosis of urothelial papilloma, in part based on the number of cell layers, and regarded all other papillary neoplasms as carcinomas. Others applied a broader definition of “urothelial papilloma” so as not to label all patients with papillary lesions with minimal cytologic and architectural atypia as having carcinoma.

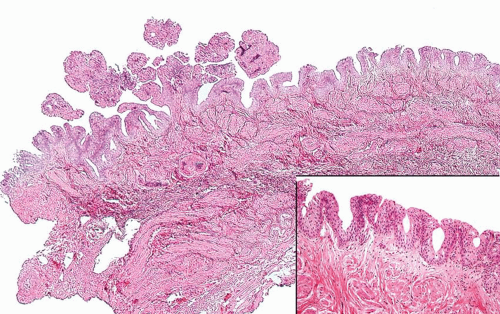

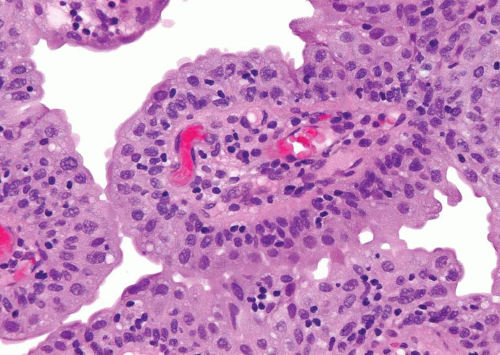

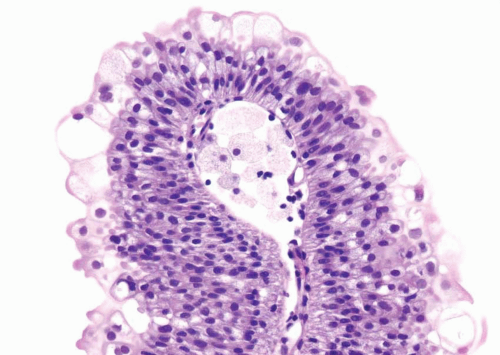

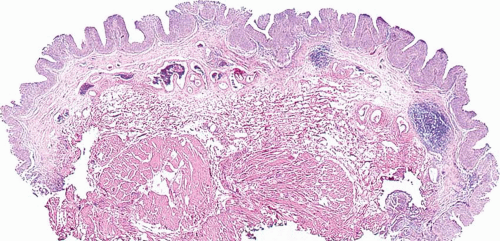

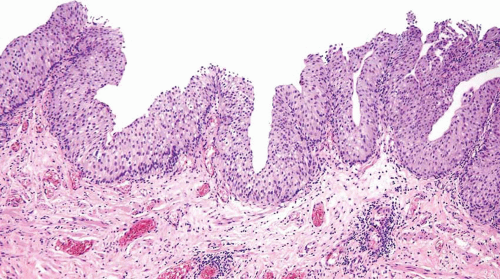

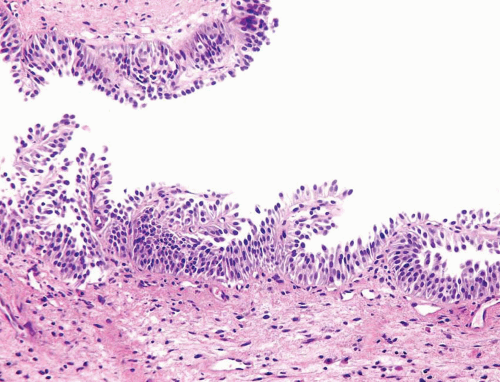

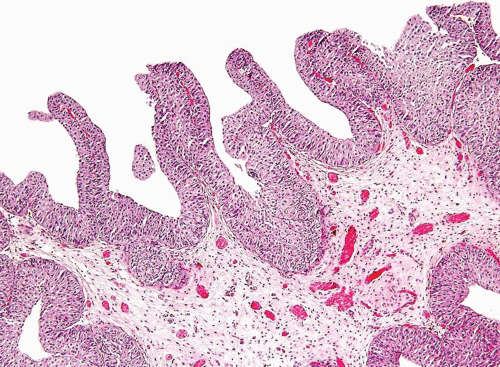

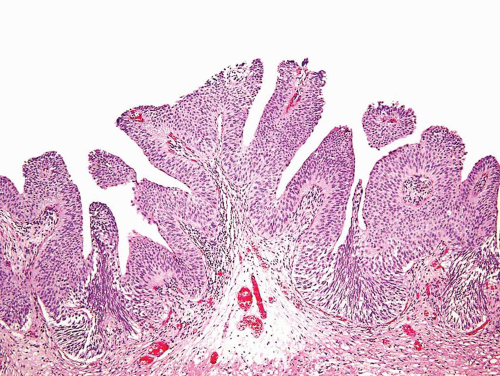

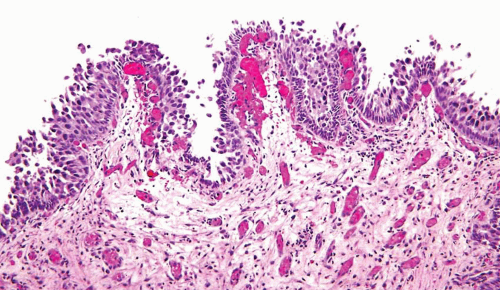

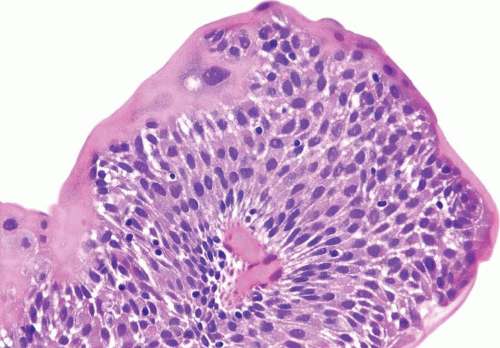

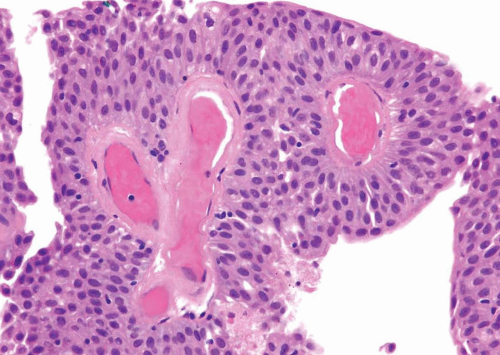

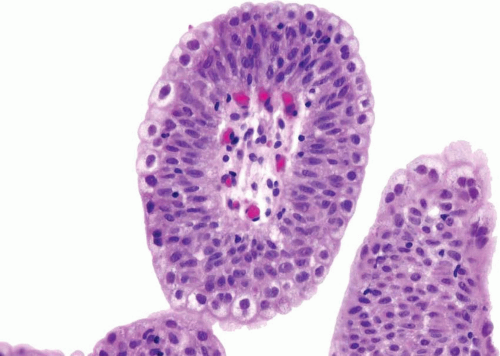

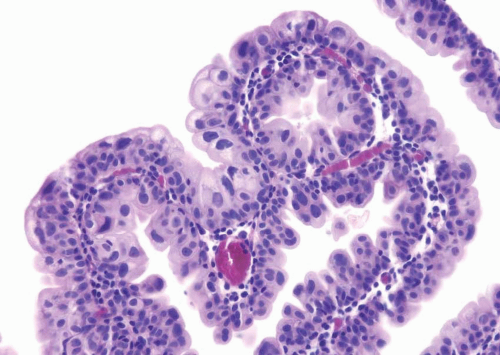

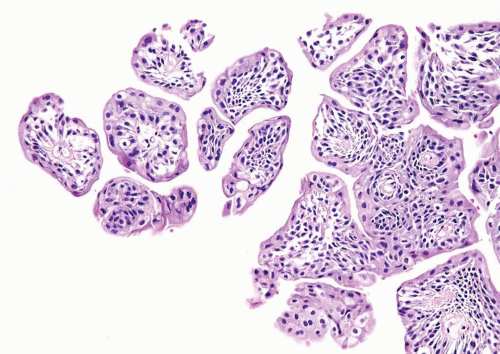

The WHO/ISUP system has very restrictive histologic features for the diagnosis of papilloma, requiring papillary fronds to be lined by normal

appearing urothelium (

Figs. 3.9,

3.10,

3.11,

3.12,

3.13 and

3.14) (efigs 3.10-3.45). Most papillomas present as single lesions that are relatively small. However, multifocal tumors and larger lesions may be seen.

Most papillomas have a simple nonbranching or minimally branching arrangement, slender fibrovascular stalks, and a predominantly exophytic pattern. In some papillomas, more complex anastomosing papillae, marked stromal edema within the papillae, and endophytic areas (areas of inverted papilloma) can be identified (

Figs. 3.15,

3.16).

Within the limits of normal urothelial thickness, there is some variability. Uncommon cases may be composed of only one to two cell layers of urothelium. There is no need to count the maximum number of cell layers, as long as it is not obviously thicker than the normal urothelial lining. In most cases, the urothelium is tightly cohesive, although in some cases, there may be the appearance of discohesion. Umbrella cells vary in their morphology from being inconspicuous to being cuboidal with slightly enlarged nuclei and paler cytoplasm to having a hobnail appearance with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Occasional cases of urothelial papilloma have an umbrella cell layer with prominent vacuolization. Single, enlarged umbrella cells may also drape themselves over several underlying urothelial cells, where the umbrella cell nuclei may demonstrate degenerative atypia. Urothelial atypia, other than that which can be seen in umbrella cells, excludes the diagnosis of papilloma. Mitotic figures are absent.

Papillomas are rare and typically, but not exclusively, occur in younger patients. Papillomas may occur in association with a prior or concurrent history of other urothelial tumors. However, if a papilloma is the first manifestation of urothelial neoplasia, only about 7% to 8% recur, typically within 5 years of the initial diagnosis (

16,

25,

27,

28,

29,

30). Lesions typically recur as papilloma and less commonly as PUNLMP or noninvasive low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. Of the three largest series on papillomas totaling 112 patients, only one patient experienced stage

progression; invasive urothelial carcinoma was found extending out of the bladder 4 years after the diagnosis of papilloma (

27,

28,

30). A caveat to this exceptional case is that the patient was immunosuppressed following renal transplantation.