CHAPTER 10 PANCREATIC AND PERIAMPULLARY RESECTION

GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND PREOPERATIVE APPROACHES

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS (See Chapter 1)

It is essential that the surgeon be familiar with the arterial variations to avoid injury and particularly to avoid hepatic ischemia in the jaundiced patient. The important variations are those of the right hepatic artery. The right hepatic artery usually crosses in front of the portal vein, but in a small percentage of cases, it passes behind the portal vein, raising a suspicion of an accessory or replaced right hepatic artery. This arises from the superior mesenteric artery and passes on the right and somewhat posterior to the common bile duct (see Chapter 1, Fig. 1-27). The difference between a true right accessory or replaced hepatic artery and a right hepatic artery passing behind the portal vein usually can be determined by palpation just above the duodenum, where a true ectopic artery will be felt.

In most cases, the right hepatic artery passes behind the bile duct, but a right hepatic artery passing in front of the common bile duct is common (Chapter 1) and should be identified during mobilization of the gallbladder and cystic duct. Unresectability is not defined by variant anatomy but rather by the local invasion of major vascular structures independent of their position. Thus the presence of an accessory or replaced right hepatic artery from the superior mesenteric artery does not preclude resection of the pancreatic head. Often the vessel will pass posteriorly and can be carefully dissected free.

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT OF RESECTABILITY

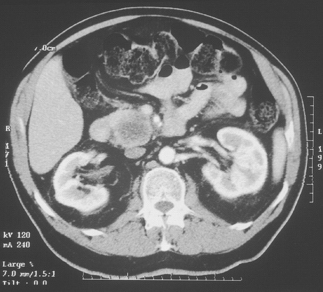

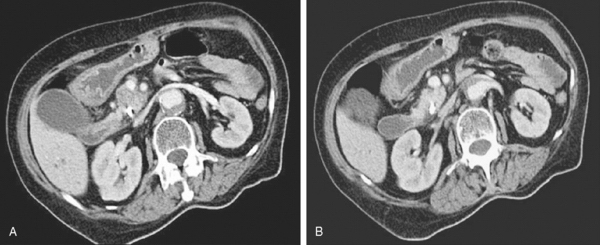

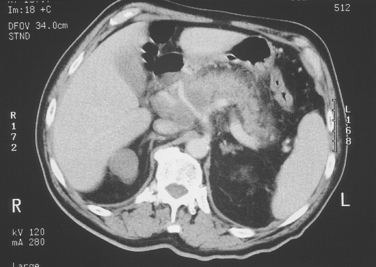

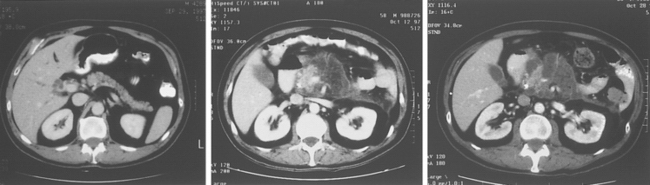

Computed tomographic (CT) scanning is the central investigation for the assessment of resectability in pancreatic cancer. Once metastatic disease has been excluded, the most important consideration as to resectability will be the degree of vascular involvement (Fig. 10-1). More subtle degrees of involvement can be suspected when the clear fat plane surrounding the celiac axis or the superior mesenteric artery is lost (Fig. 10-2).

Figure 10-1 Gross and obvious encroachment of the celiac and splenic arteries as seen on helical CT.

Arterial encroachment or encasement by adenocarcinoma of the pancreas precludes resection for cure. However, venous involvement of the superior mesenteric or portal vein does not necessarily preclude resection (Fig. 10-3). The presence of obvious enlarged varices on the CT scan almost always precludes any resection for cure. More subtle involvement of the superior mesenteric vein or the portal vein is more difficult to interpret. Nevertheless, any significant degree of venous involvement will almost always mean that there is some degree of extension of the tumor to the arteries, usually the superior mesenteric artery, by posterior encroachment behind the superior mesenteric and portal veins. Complete obstruction of the splenic vein does not preclude resection, but proximal splenic involvement raises the issue of involvement of the base of the celiac axis.

PREOPERATIVE BILIARY DRAINAGE

Prospective randomized studies have not shown a benefit to preoperative biliary drainage by the transhepatic or by the endoscopic route. Not only are these procedures not advantageous, but they may be harmful (McPherson et al., 1984; Blenkharn et al., 1984). The placement of indwelling stents inevitably contaminates the bile, produces a peripancreatic inflammatory response, and is on occasion accompanied by severe pancreatitis (Fig. 10-4) and often cannot be justified. A highly selective use of biliary drainage for those patients in whom the delay between diagnosis and resection may be prolonged is justified.

Figure 10-4 Severe pancreatitis following unnecessary endoscopic stenting for a small periampullary lesion.

ROLE OF SOMATOSTATIN

Octreotide, the octapeptide analog of somatostatin, is a powerful inhibitor of pancreatic exocrine secretion. Numerous randomized prospective trials have examined the role of prophylactic, perioperative octreotide and its impact on the outcome after pancreatic surgery (Büchler et al., 1992; Friess et al., 1995).

I believe that, as recommended by Büchler (2007) for all patients scheduled for pancreatic resections, prophylactic subcutaneous octreotide (Sandostatin), beginning with the first dose of 200 mcg given at induction, should be used. It is suggested that if the pancreas is considered high risk by the surgeon because of a soft consistency or a pancreatic duct size of less than 3 mm in diameter, the postsurgical regimen would be three daily doses of 200 mcg of octreotide for the next 5 days. Conversely, if the gland is firm with a relatively wide duct, each individual dosage would be 100 mcg.

CEPHALIC PANCREATICODUODENECTOMY (WHIPPLE OPERATION)

TECHNIQUE OF CEPHALIC PANCREATICODUODENECTOMY

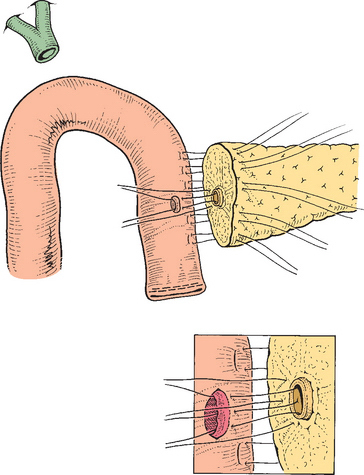

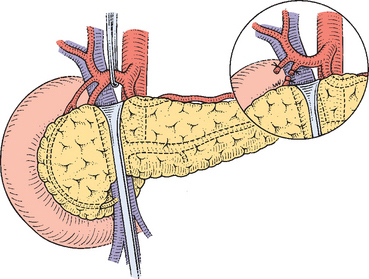

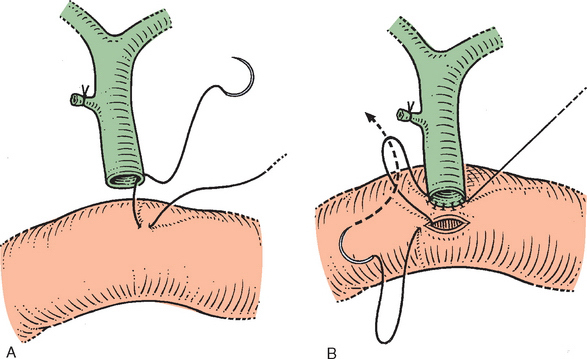

A technique in common use is described. However, I prefer the variations in technique of pancreaticojejunostomy and choledochojejunostomy, which are detailed in the following (see Figs. 10-16 and 10-17) and depicted in the videos.

Figure 10-16 A, Technique for end-to-side anastomosis of the bile duct below the hilus to the jejunum. The serosa of the jejunum is sutured to the full thickness of the bile duct. B, The jejunum is incised, and the suture is now developed as a continuous anterior layer. The posterior layer of the jejunal mucosa is not sutured directly to the bile duct mucosa. Several interrupted sutures may be inserted, however, before completing the anterior layer to approximate the mucosa. Anastomosis is now completed (see also Chapter 8).

Resection

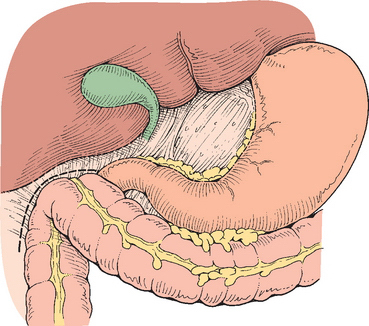

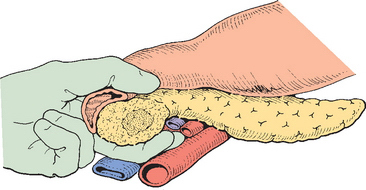

The lesion is then evaluated for resectability. The colon is mobilized (Fig. 10-5) and the inferior vena cava is dissected free of all tissue. The third and fourth part of the duodenum is reflected and the pancreas elevated so that a hand can be passed behind the pancreas to palpate the tumor mass (Fig. 10-6). This usually determines whether or not the likelihood of posterior extension to the superior mesenteric artery is present. Gross invasion of the superior mesenteric artery presupposes venous encasement and unless the artery is completely free, the procedure is terminated. The omentum is elevated and the lesser sac is entered. The omentum is detached from the colon and the inferior border of the pancreas identified. The anterior surface of the superior mesenteric vein is identified (see below), and the right gastro-epiploic vein divided and the anterior branch of the inferior pancreaticoduodenal vein ligated just below the pancreas. The middle colic vessels that drain into the superior mesenteric vein may be preserved but can be divided without consequence. The presence of any significant varices in the omentum or colonic mesentery should raise concern as to portal vein or superior mesenteric vein obstruction.

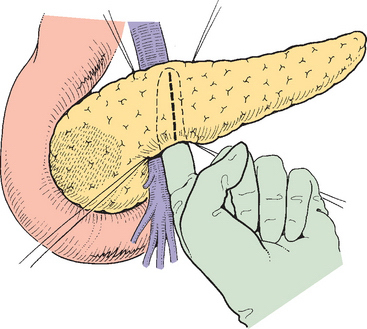

The pancreas is then elevated from the anterior surface of the superior mesenteric vein (Fig. 10-7). If this dissection plane is free and before completion of the dissection from below, attention is directed to the superior border of the pancreas, where the common hepatic artery is identified (Fig. 10-8).

The magnitude of the common hepatic artery pulsation is consciously examined to avoid a median arcuate ligament syndrome. The gastroduodenal artery is identified and if there is no adherence or encasement of the common hepatic artery, the gastroduodenal artery is doubly ligated and divided, as is the right gastric artery (see Fig. 10-8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree