Symptom

Points

Weight loss >10 %

8

Pain

5

Jaundice

4

Smoking

4

Total possible

21

Low MBSS: A

0–9

High MBSS: B

12–21

12.3 Obstructive Jaundice

Jaundice is often the first sign of pancreatic head cancer. Biliary stasis leads to a variety of secondary complications like disabling pruritus, relapsing cholangitis, anorexia, malnutrition due to malabsorption and coagulation disorders. Palliative drainage of the biliary system can be achieved by either surgical (bilio-digestive anastomosis) or nonsurgical means (endoscopic or percutaneous stent placement). For many years, stent placement has been preferred to surgical biliary diversion due to high morbidity and mortality rates associated to surgery reaching 56 and 33 %, respectively [9, 10]. During the last 20 years, improved surgical skills and facilities led to reduced postoperative complications following biliary diversion approaching the rate of established stenting procedures. Recent publications report 20 % morbidity and 4 % mortality rates after palliative biliary bypass surgery [6, 11, 12] (Table 12.2). Based on the actual data, there is still an ongoing debate concerning the best palliative treatment for malignant biliary obstruction.

Table 12.2

Morbidity and mortality of palliative bypass procedures for unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma in recent studies (after 2000)

Authors | Patients | Mortality (%) | Morbidity (%) | Length of hospital stay (days) | Median survival (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Isla et al. (2000) [18] | 56 | 0 | 35 | 14 | 6 |

Stumpf et al. (2001) [17] | 107 | 3.7 | 24 | – | 6.7 |

Urbach et al. (2003) [16] | 1,919 | 11.8 | – | – | 5.3 |

Mortenson et al. (2005) [15] | 84 | – | 25 | 12.3 | 6.2a |

Lesurtel et al. (2006) [12] | 83 | 4.8 | 26.5 | 16 | 9 |

Mukherjee et al. (2007) [14] | 108 | 6.5 | 15.7 | 11 | 6 |

Muller et al. (2008) [6] | 136 | 3 | 15 | 11 | 8.3 |

Hwang et al. (2009) [13] | 38 | 2.2 | 15.5 | 19 | 8 |

12.3.1 Nonsurgical Biliary Drainage

12.3.1.1 Percutaneous and Endoscopic Biliary Drainage

Beside numerous retrospective studies, which failed to show any difference in procedure effectiveness [19–21] between percutaneous and endoscopic biliary drainage, there are only two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the two procedures [22, 23]. One RCT [10] showed better jaundice resolution rates after endoscopic stent placement compared to percutaneous drainage (81 % vs. 61 %, respectively, p = 0.017). Moreover endoscopic drainage showed a favourable 30-day mortality rate of 15 % vs. 33 %, respectively (p = 0.016) [22]. In contrast, the second RCT documented better outcomes for biliary drainage by percutaneous stenting resolving jaundice in 71 % vs. 42 %, respectively (p = 0.03 %) [23]. In routine clinical practice, endoscopic stenting is primarily performed in conjunction with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) staging and biopsy. Endoscopic stenting offers some advantages for the patient as there is no external catheter to handle and thus less infectious risk. Percutaneous drainage constitutes an alternative, if endoscopic stenting is not feasible, but there is an increased risk of complications like biliary leakage and bleeding.

Plastic vs. Metal Stents

The incidence of recurrent jaundice following biliary stenting is highly dependent on the type of stent inserted [24]. There are two types of stents, plastic stents (polyethylene) and self-expandable metal stents. Plastic stents show a median patency rate of approximately 2–4 months [25], with early occlusion due to biofilm formation with aggregation of bacteria, protein and bilirubin. Self-expandable metal stents offer a superior median patency rate of 4–9 months [25], with intraluminal obstruction mostly due to tumour invasion. A RCT comparing plastic stent vs. metal stent placement for malignant biliary obstruction found recurrent jaundice in 43 % of patients after a median of 1 month following plastic stent insertion. In contrast, recurrent biliary obstruction after metal stent placement was reported in 18 % of cases after a median of 3.5 months [26]. Stent selection should be based on estimated overall patient survival to minimize re-interventions and hospital readmissions in the palliative setting. Additional costs for metal vs. plastic stents are balanced for patients surviving more than 6 months [27, 28].

Covered vs. Uncovered Stents

In order to reduce stent occlusion in the long term, several authors proposed during the 1990s a number of covered stents to prevent tumour invasion and intraluminal debris aggregation [29]. The advantages are referred to the anti-adherent whole wall cover of Gore-Tex, silicon and polyurethane materials. The initial results of patency rates and risk profile were encouraging, although not significantly superior compared to uncovered wallstents [30]. The efficacy of covered wallstents in the setting of unresectable malignant biliary obstruction has been assessed [31]. The reported 3-, 6- and 12-month patency rates comprised 90, 82 and 78 %, respectively [31]. A meta-analysis showed a significantly longer duration of patency for covered compared to uncovered stents [32]. To sum up, uncovered stents have a trend towards increased obstruction, when compared to their covered counterparts.

12.3.2 Surgical Drainage

12.3.2.1 Surgical Diversion Techniques

Recent publications mainly discuss four different bilio-digestive derivation techniques in the palliative setting: cholecystoduodenostomy (CCD), cholecystojejunostomy (CCJ), choledochoduodenostomy (CDD) and choledochojejunostomy (CDJ). CCD and CCJ can be easily performed laparoscopically using a linear staple device. However, compared with an anastomosis to the main hepatic duct, they are associated with higher rates of failure and recurrent jaundice [16, 33]. A direct comparison between CCJ or CCD and CDD showed superior drainage and a significantly lower recurrence rate of biliary obstruction (<8 %) for choledochal anastomosis [34, 35]. These results were explained by a tumour invasion of the hepatocystic confluence in 50 % of the cases [36]. Similarly, current literature suggests a threefold higher rate of re-interventions for CCJ compared to an anastomosis to the main hepatic duct [16]. Considering these results, diversion techniques with an anastomosis to the main hepatic duct should be preferred [34, 37]. Furthermore, CDJ or hepaticojejunostomy with a Roux-en-Y reconstruction offers an effective biliary drainage and a favourable recurrence rate (<13 %) [38].

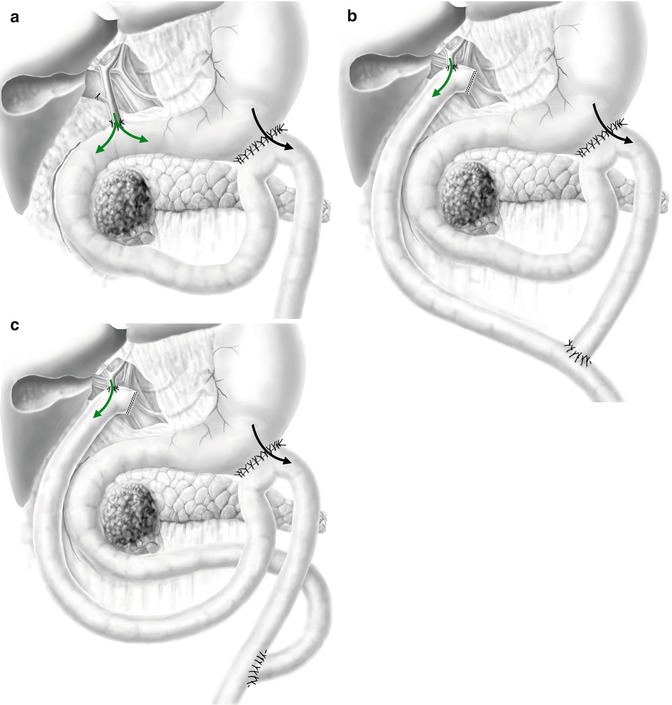

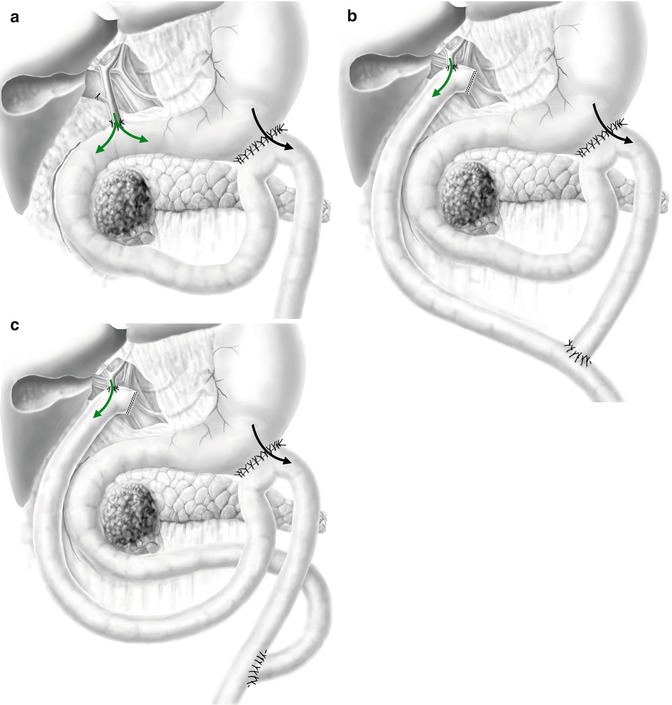

Finally, a CDJ is recommendable, if there is any risk for duodenal tumour obstruction or if mobilization of the duodenum does not seem feasible. Nevertheless, a classic CDD could also be performed in most cases (Fig. 12.1a–c).

Fig. 12.1

(a–c) The 3 main double bypasses performed for unresectable pancreatic head cancer described in the literature. (a) Choledochoduodenostomy (the duodenum needs to be mobile) + gastrojejunostomy 30 cm after Treitz’s angle. (b) Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy + gastrojejunostomy 30 cm after Treitz’s angle. (c) Hepaticojejunostomy and gastrojejunostomy on the same Roux-en-Y limb (green arrow, bile flow; black arrow, food passage) (The authors of this chapter would like to thank Stefan Schwyter for his help with these drawings)

12.3.3 Surgical Bypass vs. Stent Drainage

There are only three RCTs comparing the efficacy of surgical vs. plastic endoscopic drainage for obstructive jaundice [39–41]. Plastic stents were used in all the trials (Table 12.3) [39–41]. Initial successful drainage was achieved in 95 % of the cases with both methods. Only one study found a lower mortality rate after endoscopic stenting compared to surgical bypass (3 % vs. 14 %, respectively, p = 0.006) [39], although post-interventional complication rates were higher after surgery compared to endoscopic stenting (29 % vs.11 %, respectively, p = 0.02) [39]. Finally, re-interventions for recurrent jaundice were up to seven times [39] more frequent after endoscopy compared to surgery [39, 40, 42].

Table 12.3

Randomized controlled trials comparing endoscopic plastic stent placement with surgical derivation for obstructive jaundice in the setting of unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Sheperd et al. (1988) [40] | Andersen et al. (1989) [41] | Smith et al. (1994) [39] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Surgery | Stent | Surgery | Stent | Surgery | Stent | |

Patients | 25 | 23 | 19 | 25 | 101 | 100 |

Successful drainage (%) | 92 | 91 | 76 | 96 | 94 | 95 |

Median length of hospital stay | 13 | 8 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 19 |

Morbidity (%) | 40 | 22 | 26 | 36 | 29 | 11* |

Recurrent jaundice (%) | 0 | 43** | 16 | 28 | 2 | 36 |

30-day mortality (%) | 20 | 9 | 31 | 20 | 15 | 8 |

Median survival (weeks) | 18 | 22 | 14 | 12 | 26 | 21 |

Two retrospective analyses and one RCT compared surgical drainage with metal stent placement for obstructive jaundice [38, 43, 44]. Immediate success of biliary drainage between the two techniques was similar, ranging from 95 to 100 % [41]. Nevertheless, a tendency towards an increased early complication rate was found in the case of a surgical approach (p = 0.1) [43]. Furthermore, surgery led to a prolonged mean hospital stay (32 ± 4 days and 12 ± 1 days, respectively, p = 0.002). In contrast, late complications, including recurrence of jaundice, were more common after metal stent placement (42 and 10 %, respectively, p = 0.04) [43]. One retrospective study failed to show any significant difference in terms of complication rates but highlights a higher rate of hospital readmissions after stenting compared to surgical approach (40 % vs. 13 %, p < 0.05) [38]. Of note, total length of hospital stay ultimately favoured the surgical approach over stenting procedures (mean 34 vs. 10 days, p >0.05) [38]. A RCT assigned patients with biliary obstruction due to metastatic pancreatic cancer either to endoscopic metal stent or to surgical bilio-jejunostomy (n = 15 in each group) [44]. Of note, no sample size calculation was performed. There was no difference between the two groups regarding complication rates, readmissions for complications and duration of survival. In this specific population with metastatic disease, they found that the overall total cost of care that included initial care and subsequent interventions and hospitalizations until death was lower in the endoscopy group, when compared with the surgical group (USD 4,271 ± 2,411 vs. 8,321 ± 1,821, p = 0.0013). In addition, the quality of life scores were better in the endoscopy group at 30 days (p = 0.04) and 60 days (p = 0.05) [44].

In 2006, a meta-analysis of 21 studies summarizing 1,454 patients was published [24]. Similar to the previously discussed RCTs, they found an increased complication rate (RR = 0.6, p < 0.0007) and an 18-fold reduction of re-interventions (RR = 18.9, p < 0.00001) after surgical drainage, when compared to endoscopic stent placement. The authors concluded that endoscopic placement of a metal stent has the most favourable risk-outcome profile. Recurrent obstruction and the subsequent need of re-interventions were significantly reduced at 4 months and before death after surgical bypass compared to endoscopic stent placement (RR = 0.44 and RR = 0.52, respectively).

In summary, patients with an estimated survival of less than 6 months benefit more from interventional stent placement in terms of morbidity and length of hospital stay. On the other hand, patients whose life expectancy exceeds 6 months may benefit from a more lasting solution with a decrease need for re-interventions over time. In such a case, a surgical bypass procedure can be recommended, especially if the diagnosis of unresectability of the tumour is diagnosed at laparotomy.

12.4 Malignant Gastric Outlet Obstruction

12.4.1 Palliative Gastroenterostomy

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) is a common complication of advanced pancreatic cancer. Surgical management of duodenal or gastric tumour obstruction implies the creation of a gastrojejunostomy. However, the indication for preventive surgical treatment in the palliative setting is controversial, as not every patient develops GOO with disease progression. While only 20 % of patients initially present with symptoms of GOO, 30–50 % develop GOO during the course of their disease [3, 45]. If unresectability of the tumour is diagnosed at laparotomy, patients benefit from double bypass procedures in the long term, as this approach may reduce the incidence of GOO and obstructive jaundice [12]. Of note, a double bypass procedure including a gastrojejunostomy does not increase postoperative morbidity compared to biliary bypass alone [12, 46]. In contrast, a gastrojejunostomy performed in a second step with arising symptoms of GOO has a postoperative mortality risk of up to 22 % [47, 48].

Two RCTs and one prospective cohort study aimed at answering the question whether a prophylactic gastroenterostomy should be performed in asymptomatic palliative patients (Table 12.4) [46, 49, 50]. Lillemoe et al. [49] randomized 87 patients with unresectable periampullary cancers diagnosed upon laparotomy without impending risk of GOO to either retro-colic gastrojejunostomy (n = 44) or no gastrojejunostomy (n = 43). They reported no postoperative mortality and a median survival of 8.3 months in both groups [49]. Within the group without prophylactic gastrojejunostomy, 8 patients (19 %) developed late GOO requiring a therapeutic intervention compared to none in the prophylactic treatment arm. Postoperative morbidity (32 % vs. 33 %) and length of hospital stay (8.5 vs. 8 days) did not differ significantly between the two groups [49]. Similarly, 65 patients were randomized to receive either a single bypass (29 patients with bilio-digestive anastomosis) or a double bypass (36 patients with both bilio-digestive and gastroenteric anastomoses) at the time of intraoperative diagnosis of unresectable periampullary cancer [46]. To be included in the study, patients were required to present neither signs of GOO nor any endoscopic treatment for more than 3 months. Late GOO developed in two patients in the double bypass group (5.5 %) compared to 12 patients, who received a single bypass (41.4 %), p = 0.001 [46]. There was no significant difference in postoperative morbidity including delayed gastric emptying (17 % vs. 3 %, p = 0.12), median length of stay (11 vs. 9 days, p = 0.06), quality of life and median survival (7.2 vs. 8.4 months, p = 0.15) [46]. Finally, 66 patients with unresectable periampullary adenocarcinoma were prospectively enrolled to receive either a single bilio-digestive bypass (n = 22) or, in the presence of GOO, a double bypass (n = 44) [50]. The authors did not report any difference in postoperative morbidity and mortality. Of note, seven patients in the single bypass group (31 %) developed late GOO within 6 months after the bypass [50].

Table 12.4

Prospective studies comparing double bypass with single bilioenteric bypass for unresectable pancreatic cancer

First author (year) | Study design | Patients | Morbidity (%) | GOO (%) | Survival (months) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Double bypass | Single bypass | Double bypass | Single bypass | Double bypass | Single bypass | Double bypass | Single bypass | ||

Lillemoe et al. (1999) [49] | RCT monocentre | 44 | 43 | 32 | 33 | 0* | 19 | 8.3 | 8.3 |

Shyr et al. (2000) [50] | Prospective cohort trial | 44 | 22 | 11 | 14 | nd | 32 | 5 | 8 |

Van Heek et al. (2003) [46] | RCT multicentre | 36 | 29 | 11 | 8 | 6* | 41 | 7.2 | 8.4 |

Finally, a recent meta-analysis including the aforementioned studies summarized 218 patients in total [51]. The results confirmed a significant lower risk of late GOO after prophylactic double bypass compared with bilioenteric bypass only [51]. Again double bypass surgery did not add morbidity or mortality, when compared with single bypass or no bypass procedures. The authors did not find any increased rate of delayed gastric emptying after gastrojejunostomy, which is of special concern in this group of patients. They conclude that there is sufficient evidence to recommend prophylactic double bypass surgery for patients found to have unresectable periampullary malignancy diagnosed at laparotomy and who need a bilioenteric diversion [51].

Former gastroenteric diversion techniques for malignant GOO aimed at placing the anastomosis as far as possible from the actual tumour site. Therefore, gastrojejunostomy was usually performed mainly in an ante-colic fashion. However, there is now evidence that retro-colic gastrojejunostomy is associated with a lower rate of postoperative delayed gastric emptying [52]. Surgeons at the Johns Hopkins Hospital assessed the rate of postoperative delayed gastric emptying following gastrojejunostomy in the palliative setting [2, 53]. The first retrospective study compared complications of ante- vs. retro-colic gastrojejunostomies. The authors reported delayed gastric emptying in 6 % of the patients operated in a retro-colic fashion compared to 17 % in the group with ante-colic gastrojejunostomy [53]. Similarly a subsequent study evaluated 180 patients, who received a retro-colic gastrojejunostomy and showed a 9 % rate of delayed gastric emptying [2]. Finally, a RCT documented a 2 % rate of delayed gastric emptying in patients receiving a prophylactic retro-colic gastrojejunostomy after being diagnosed with unresectable disease upon laparotomy [49].

The outcome of three different types of gastrojejunostomies in patients with malignant GOO was compared in a RCT [54]. A total of 45 patients were enrolled. One-third received a gastrojejunostomy with an anastomosis located 20 cm distal to the Treitz’s ligament. The second group received the same intervention associated with duodenal partition with a linear stapler 1 cm distal to the pylorus. A reconstruction with a Roux-en-Y limb located 60 cm distal to the bilioenteric anastomosis was performed in the third group. Patients within the first group were more frequently symptomatic and showed prolonged postoperative gastric emptying [54]. “Food re-entry” was documented by upper gastrointestinal imaging in 21 % of the patients within the first group. Therefore, the authors proposed duodenal partition as an easy procedure to improve outcome after gastrojejunostomy 20 cm distal to the Treitz’s ligament [54].

12.4.2 Duodenal Endoscopic Stenting

At the beginning of the 1990s, after oesophageal stenting has been established, the first duodenal stents were placed for malignant outlet obstruction. First outcome reports of the new technique were encouraging. Obvious benefits comprised reduced invasiveness and faster recovery to oral intake [55]. Nevertheless, subsequent studies including a longer follow-up period reported stent-specific complications counterbalancing the initially appraised advantages [56].

Three RCTs compared duodenal stent placement with surgical gastrojejunostomy for malignant GOO (Table 12.5) [57–59]. These studies shared one shortcoming, which is a relatively small number of patients (n = 18, 27 and 39, respectively). Two RCTs (n = 18 and 27) favoured duodenal stenting over surgery because of a shorter length of hospital stay, shorter time to oral intake and decreased pain scores associated with stenting [57, 58]. A systematic review summarized two of the three RCTs with additional prospective and retrospective studies in order to compare endoscopic stenting with gastrojejunostomy [56]. The review evaluated 1,046 patients after a duodenal stenting procedure and 297 patients who underwent a gastrojejunostomy in the palliative setting [56]. A significant shorter time to oral intake and a shorter length of hospital stay favoured duodenal stenting compared to the surgery group (mean hospital stay 7 vs. 13 days, respectively) [56]. There was neither any difference between groups in terms of persistence of obstruction nor early and late major complications. Stent migration and stent obstruction by tumour ingrowth or food were frequent complications in the stenting group, whereas complications after gastrojejunostomy included anastomotic leakage and dysfunction. However, the re-intervention rate was significantly higher following duodenal stenting compared to surgery (18 % vs. 1 %, respectively). In conclusion, the authors recommended duodenal stenting in patients with a short life expectancy, because of the advantages in early time points, but they supported surgery for patients expected to live more than 2 months in order to avoid frequent re-interventions.

Table 12.5

RCTs comparing duodenal stent and gastrojejunostomy for malignant outlet obstruction in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer

First author (year) | Intervention | Patients | Success of intervention (%) | Resolution of GOO (%) | Length of hospital stay (days) | Morbidity (%) | Follow-up (months) | 30-day mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Fiori et al. (2004) [57] | oGJ | 9 | 100 | 89 | 10 | 22 | 3 | – |

Stent | 9 | 100 | 100 | 3.1* | 22 | 3 | – | |

Mehta et al. (2006) [58] | lapGJ | 14 | 93 | – | 11 | 62* | – | 23 |

Stent | 13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|