- Patients need to be given timely information about prognosis and quality of life, whether they are on dialysis, choose to stop or even choose not to start dialysis in the first place.

- Patients with stages 4–5 chronic kidney disease (CKD) often have slowly progressive disease and may survive many months or even years without dialysis. However, prediction of survival can be difficult and patients can deteriorate rapidly, have a slow steady decline in function or a decline punctuated by recurrent acute problems.

- In some patients dialysis may offer little or no significant survival rate improvement.

- There is increased recognition of a need for coordinated management of end-of-life care for patients with end stage renal failure (ESRF).

- For patients who choose not to dialyse, it is important to offer treatment for other aspects of CKD, e.g. erythropoietin therapy and phosphate control.

- Symptoms such as pain, dry skin, itching, nausea and vomiting, constipation, anorexia, muscle cramps, abdominal bloating, insomnia and fatigue all need to be considered and treated where possible.

- Collaboration with palliative care services may be appropriate.

Introduction

As with any major organ failure, severe renal disease (stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD) or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), or glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <15 mL/min) is associated with significant morbidity and increased mortality. Over the last three decades, long-term renal replacement with dialysis has become increasingly available to older people and those with greater comorbidity. However, it is now recognized that continuing or initiating dialysis may not always offer an improved quantity or quality of life; indeed, we run the risk of worsening patient outcome. In this context, palliative (also referred to as conservative, supportive or end-of-life) treatment options should be part of our management of renal failure. We need to offer realistic choices to patients with end stage renal failure (ESRF) but can only do so if appropriate services and support are in place.

Which Renal Patients Need Palliative Care?

Palliative care is important for many patients with ESRF. For the majority, if not all patients, end-of-life issues should be addressed prior to the introduction of renal replacement therapy. Dialysis is, after all, a treatment and not a cure. Recognizing the need for palliative care in patients with ESRF is challenging. This is largely due to unpredictable illness trajectories often influenced by comorbidities. Murray et al. (2005) suggest we ask the question, ‘would I be surprised if my patient were to die in the next 12 months?’ If the answer is no, the clinician should be considering if such a person has palliative care needs. Recent evidence has shown the question to be a more accurate predictor of prognosis than previously proposed variables, such as plasma albumin. In the United Kingdom, a general practice initiative called the Gold Standards framework can help both identify patients and then improve their care. This approach could apply to patients who are deteriorating despite dialysis, those who choose not to have dialysis or those who would not tolerate dialysis and are treated conservatively. Patients may also choose or be advised to stop dialysis, perhaps because of the development of intercurrent illness, which may make dialysis medically impossible, or there may be an acknowledgement of a failure to tolerate, or benefit from, dialysis treatment.

The Extent of the Clinical Need

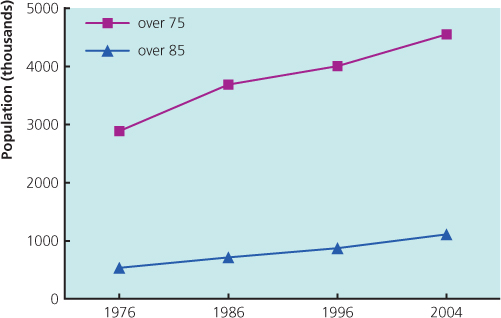

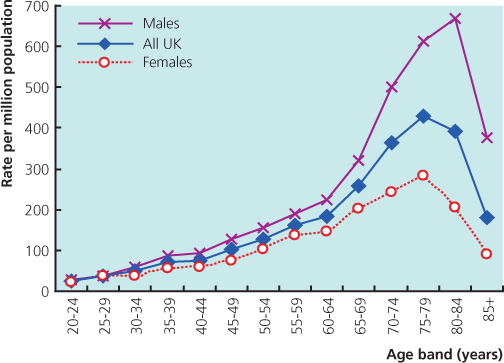

The number of patients requiring dialysis has increased steadily, and is predicted to continue to rise for the next 20 years. Older people receiving haemodialysis will constitute a major proportion of this increase due to the high incidence of renal failure in this group (Figure 9.1) and the increasing age of the population (Figure 9.2). The incidence of dialysis-requiring renal failure increases with age, peaking at 567 per million population (pmp) in males over 80 years of age. This compares with 45 pmp in men in their 20s. This may underestimate the true incidence of ESRF due to unrecognized or unreferred renal failure.

Figure 9.1 Renal replacement therapy (RRT) incidence rates by age and gender in 2009. The overall peak is in the 75–79 age band.

(Source: Cawskey et al. (2010) UK Renal Registry. See References

The older group of patients has a high level of comorbidity. Around 67% of patients over the age of 65 commencing dialysis have one or more significant comorbidities that may adversely affect survival. Age and comorbidity are strongly linked in dialysis candidates; comorbidity is one factor that contributes to high mortality rates on dialysis, with 28% of patients over 85 years old dying in the first 90 days of starting dialysis, and this in selected patients for whom it was thought dialysis would be beneficial.

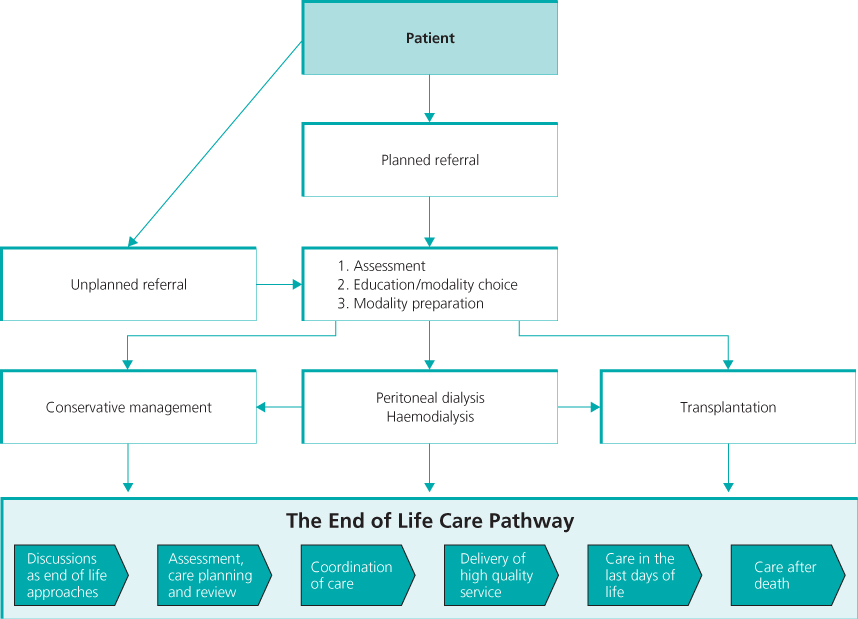

This need for coordinated management of end-of-life care for patients with ESRF has been recognized in the National Service Framework for Renal Services (Box 9.1). This has both acknowledged this important phase of patient care and set a series of standards for the delivery of end-of-life care to patients with renal disease (Box 9.2). In addition, the UK CKD guidelines recommend referral or discussion of all people who have stage 4 or 5 CKD to nephrology services for an assessment, even if it is thought that dialysis will not be appropriate (e.g. terminal malignancy, terminal cardiac or lung disease). More recently, the End of Life Care strategy (Department of Health 2008) stated that palliative care should be provided on the basis of need not diagnosis, followed by End of life care in advanced kidney disease: A framework for implementation (NHS Kidney Care 2009) which aimed to raise the quality of end-of-life care for kidney patients (Figure 9.3). These government guidelines have been important in the development of renal palliative services, recognizing the clinical need and incorporating emerging evidence.

Figure 9.3 The pathway for the management of advanced kidney disease recognizes the importance of an end of life care pathway for all ESRF patients regardless of treatment modality.

(Source: NHS 2009

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree