Fig. 25.1

Lytic lesion in the left proximal femur of a 40-year-old male. Note the bony destruction and lack of blastic response

Fig. 25.2

Proximal femoral metastatic deposit secondary to transitional cell carcinoma. The isolated lesser trochanter fracture is considered pathognomonic of a sinister cause

New presentations are advised to have a Technetium-99 bone scan. It will not necessarily determine primary lesions but can assist in identifying if a lesion is monostotic or polyostotic (Fig. 25.3). This can help look for other sites of potential disease and delineate those patients for whom curative resection may be intended. It also acts as a baseline for response to treatment. Surgeons must note that bone scans are only hot if osteoblastic activity is present. Some cancers can cause lysis without osteoblastic growth and will be cold. The classic example is myeloma. Renal cell tumours may also exhibit this behaviour.

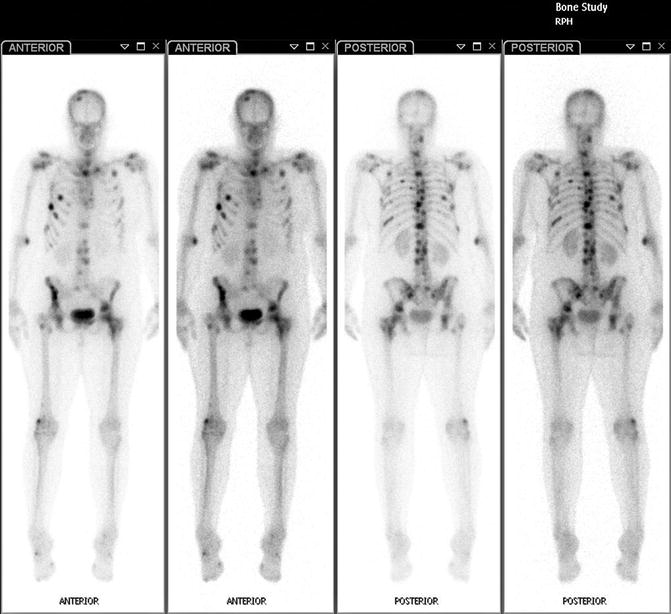

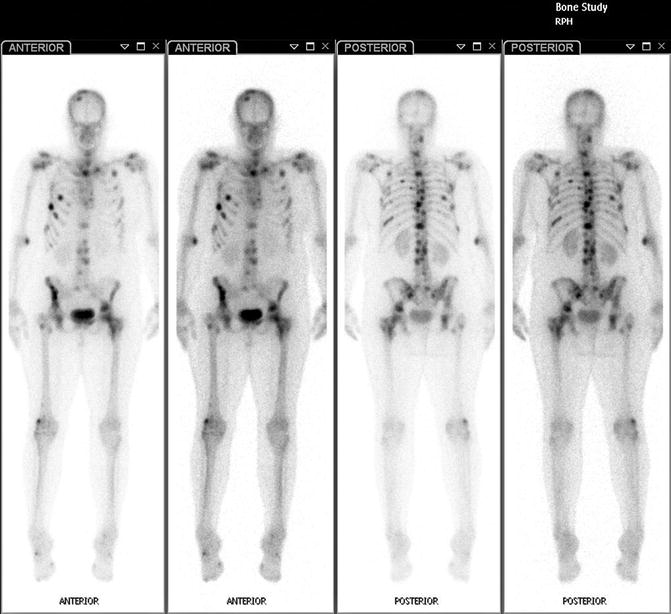

Fig. 25.3

Technetium-99 bone scan of a patient with breast cancer. The disease has metastasised throughout the skeleton

CT scanning of lesions is generally of little use in diagnosis, although it may help in surgical planning. Scanning of the viscera, however, is probably the single most high-yield investigation for determining primary lesions. CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis can detect the primary tumour in 85 % of cases [6] (Fig. 25.4). Importantly, if it fails to do so, then it is unlikely that further invasive investigation will assist.

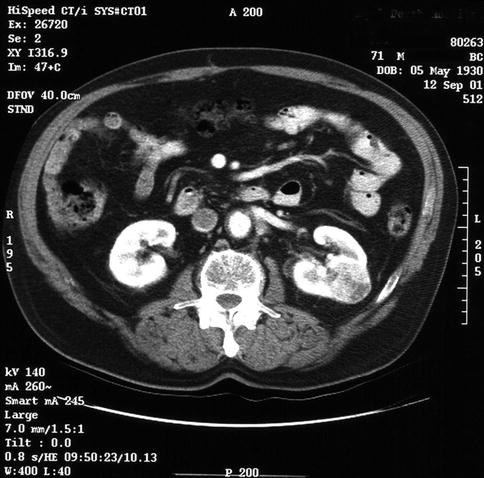

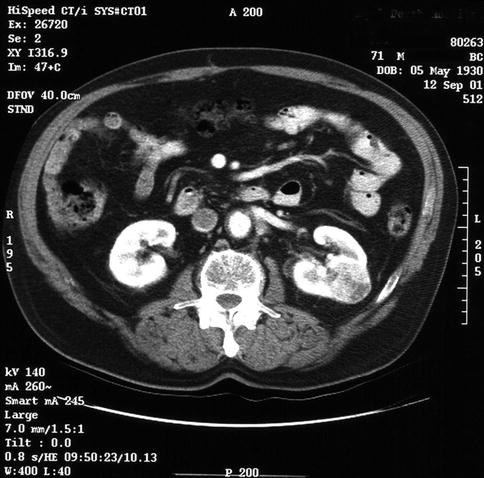

Fig. 25.4

Selected CT slice of a patient who presented with a lesion in the proximal humerus. Investigation revealed a mass in the left kidney. Subsequent biopsy demonstrated a renal cell carcinoma

Positron emission tomogram (PET) scanning has been examined recently to aid in this situation. It possesses greater diagnostic accuracy in locating small (5 mm) lesions. As such it is increasingly being used in lesions with unknown primary tumours. Its other use is determining patients for whom curative resection may be considered. It is generally only available in tertiary referral hospitals, limiting its use.

25.4.4 Biopsy

In cases where the diagnosis is unclear, a biopsy is the next step. Even if the diagnosis is clear, it is common practice to send operative material for histopathology to confirm the clinical suspicion.

We recommend discussion with an orthopaedic oncologist if the diagnosis is in doubt prior to performing a biopsy. It may not be necessary for the patient to be transferred but can prevent problems with subsequent treatment. Certain centres have radiology staff capable of performing biopsies under CT or US guidance.

The biopsy can be as simple as sending reamings from intramedullary (IM) nailing or as a separate procedure prior to planned reconstruction. When performing open biopsy the principles are based on the need to cause minimal contamination. If wide resection is subsequently needed, the biopsy tract must be excised with the lesion as it is considered contaminated with malignant cells.

Longitudinal incisions should be used violating as few compartments as possible. Neurovascular structures should be avoided and meticulous haemostasis is required. Drains should be placed at the inferior apex of the wound, if required.

Material should be sent for both histological analysis and bacterial culture and sensitivity. Prior discussion with a pathologist can aid in deciding what samples the medium should be transported in (i.e. fresh or formalin).

25.5 Management

Treatment for patients with MBD is primarily palliative, with the goals of limiting pain and rapidly restoring function. The aims for each patient will vary depending on the situation. Some patients will require surgery to facilitate community ambulation, whilst others simply need stability to allow nursing care.

The likely outcome and risks involved need to be clearly communicated to the patient and family.

Management of these patients can be divided into the preoperative optimisation, operative planning and intervention followed by postoperative rehabilitation and adjuvant treatment.

25.5.1 Preoperative Assessment

25.5.1.1 Medical Optimisation

Patients with MBD often suffer from other medical co-morbidities and the sequelae of their cancer. Malnourishment, anaemia, coagulopathy and hypercalcaemia can be present. The clinician should be alert to these possibilities. Early involvement of other medical disciplines and the anaesthetist may be required. Spinal anaesthesia may be favoured if lung function is compromised, though it is contraindicated if central metastases are present due to the risk of coning. Malignancy increases the risk of thromboembolic disease, and we recommend routine use of mechanical prophylactic devices, specifically intermittent pneumatic compression pumps. Chemical prophylaxis is indicated if it does not interfere with planned surgery or anaesthesia. Hypercalcaemia, whilst rare, increases the risk of adverse outcomes in the perioperative period. Correction can usually be achieved with intravenous fluid and bisphosphonate infusions.

25.5.1.2 Embolisation

Renal and thyroid carcinoma lesions may be highly vascular. Embolisation is advisable to decrease the risk of bleeding. This should be performed even if closed techniques such as intramedullary nailing are to be employed. CT angiography can provide an idea of the vascularity of the lesion. Embolisation should be performed within 48 h and preferably 24 h prior to surgery to provide optimal effect (Fig. 25.5a, b).

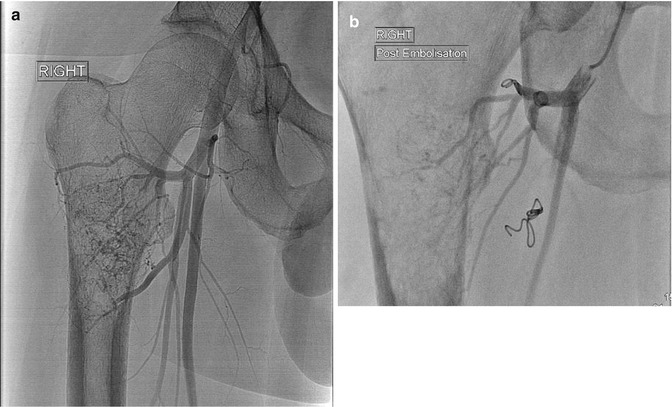

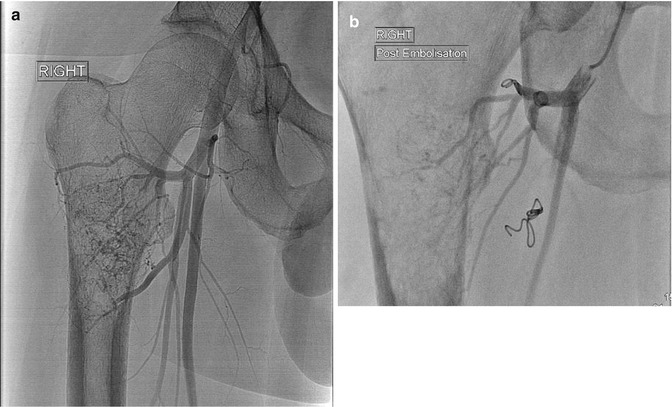

Fig. 25.5

(a, b) Pre- and post-angiography and coiling of a highly vascular renal cell carcinoma deposit in the right proximal femur. The coils and decreased flow can be seen

25.5.1.3 Adjuvant Treatment

The treating surgeon should be aware of the principles of adjuvant therapies. These include radiotherapy and chemotherapy including bisphosphonates. Radiation therapy is virtually always used postoperatively. It helps alleviate pain and “mops up” tumour cells dispersed through operation. The entire bone is included. A single course is usually all that is required. When operating through the skin that has previously been irradiated, it is important to know the dosage. Wound healing complications can be expected if cumulative dose was over 50 Gy; 60 or more Gy will almost guarantee wound breakdown.

Chemotherapy can impair wound healing. Surgery should be delayed until after the effects on neutrophils have ceased. Because of the variability between agents, surgeons should consult their oncology colleagues preoperatively.

25.5.2 Operative Planning and Surgery

There are several important principles in the surgical treatment of MBD. It is established that surgical stabilisation increases patients’ ability to ambulate, be discharged home and achieve pain relief. Decision-making needs to be individualised. The period of recovery or protected rehabilitation should not be longer than the anticipated life expectancy. Paradoxically, this often requires the use of more invasive surgical techniques to facilitate stability and early pain-free function. Surgeons should aim to undertake only one operation to stabilise a lesion.

Broad principles are outlined below [4]:

1.

Prognosis guides treatment. Patients with life expectancy less than 6 weeks should be treated with analgesia and radiotherapy. For a prognosis of 6 weeks to 6 months, internal fixation using osteosynthesis is recommended. If the patient is likely to live longer than 6 months, arthroplasty or endoprosthetic reconstruction should be strongly considered.

2.

All affected areas of the bone should be considered in the proposed reconstruction.

3.

Mechanical stability that allows immediate use and weight bearing must be obtained.

4.

Radiotherapy is administered post surgery. This reduces pain and helps to clear cancer cells disseminated locally by the surgery.

Determining the prognosis is one of the most difficult aspects of managing these patients, yet it is critical to outcome. Typically, clinicians have a tendency to underestimate the patients’ life expectancy. This has the potential to under-treat and place patients at risk for failure of fixation and further surgery (Fig. 25.6). Scoring systems are available to help, but often consultation with the patients’ oncologist or general practitioner may provide the most useful assessment. The following features are associated with a better prognosis:

Fig. 25.6

Example of fatigue failure of osteosynthesis. The patient had myeloma affecting the right proximal femur. Intramedullary nail with cement augmentation was used. The patient outlived the implant

1.

Primary tumour breast, prostate, myeloma or lymphoma

2.

Solitary skeletal metastasis

3.

Absence of visceral metastasis

4.

Absence of pathological fracture

Renal cell carcinoma is a tumour that is difficult to predict. Its biological activity can be highly variable as is the prognosis. We encourage surgeons to seek expert opinion when dealing with this tumour.

Management of long bone lesions varies with the anatomical site. The femur and the humerus are the most commonly affected bones. In the lower limb IM nailing is the treatment of choice. It carries the advantages of whole bone protection, minimally invasive insertion and resistance to axial loading. The decreased soft tissue insult and improved mechanical strength facilitate early weight bearing and rehabilitation. In the femur we advocate the use of long cephalo-medullary nails. These maximise the amount of bone protected and reduce the need for re-operation [7, 8].

The main disadvantage with IM nailing is the embolisation of tumour, fat and thrombus to the lungs with resulting potential cardiopulmonary compromise. This phenomenon is also seen in trauma surgery. However, the mortality rates are increased in the MBD population. It is thought to be due to increased permeability of the bone coupled with increased vascularity. The effect is magnified in bilateral disease and in the intact bone.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree