Open Bariatric Operations

J. Wesley Alexander

During the past two decades, there has been a major increase in the number of laparoscopic bariatric procedures compared to open procedures for the surgical treatment of morbid obesity. The advantages of the laparoscopic procedures have been improved cosmesis (lack of a long scar), a slightly decreased mortality rate (approximately 0.2% vs. 0.4% related somewhat to patient selection and characteristics) and a reduction in postoperative incisional hernias. However, the laparoscopic procedures have an increased leak rate, a higher rate of bleeding and small bowel obstruction and an increase in costs. The amount of long-term weight loss is similar for open vs. laparoscopic procedures as is improvement in co-morbidities and quality of life.

The selection of open vs. laparoscopic procedures depends in large part upon the experience of the surgeon and the desire of the patient. However, additional consideration for open procedures should be made in patients who are extremely obese (e.g., BMI >60), have had previous gastric procedures or prior operations in the central subdiaphragmatic region or with the need for additional intraabdominal operations or revision of prior bariatric procedures. Furthermore, there is sometimes a need for conversion of a laparoscopic to an open procedure. Therefore, it is mandatory that anyone who does laparoscopic bariatric procedures be qualified to do open procedures as well.

This chapter will discuss gastric bypass, biliopancreatic diversion, sleeve gastrectomy and revisions, but not various types of gastric banding as nearly all of these are done laparoscopically.

Indications for bariatric surgery should follow guidelines by the NIH and ASMBS which generally include a BMI >40 or >35 with significant co-morbidities.

Untreated coronary artery stenosis needs correction before any major surgical procedure, but hypertension, cardiovascular disease, severe sleep apnea, severe diabetes, advanced renal disease and thromboembolic disease should not themselves prevent the performance of needed bariatric surgery.

In patients who have had prior gastrointestinal surgery, obtaining and reviewing the operative report is essential.

In patients who have had prior bariatric procedures, an upper GI series and endoscopy are needed.

Preoperative endoscopy should be done in patients who have a history of reflux disease.

Some surgeons perform preoperative evaluations for the presence of H. pylori, but this is unnecessary in patients who have no history of reflux symptoms or ulcer disease.

Preoperative weight loss has been mandated in some programs to reduce liver size, but is unnecessary in open procedures.

To reduce skin organisms, the patient should shower with chlorhexidine the night before as well as the morning of operation.

A laxative is given the night before operation.

Preoperative oral neomycin/metronidazole is helpful in reducing both gastric and intestinal organisms.

All patients should undergo psychiatric evaluation, nutritional counseling, and physical therapy counseling preoperatively.

All patients should attend support groups preoperatively.

Positioning

Patient must be placed supine on the operating table being careful to avoid any pressure points to prevent rhabdomyolysis.

Place both arms out being careful to prevent any stretch on the brachial plexus.

Management of the Incision and Prevention of Wound Infection

All patients should receive preoperative systemic antibiotics. Cefazolin is used widely for this. The initial dose should be based on weight, giving 2 grams for patients under 300 pounds and 3 grams for patients weighing more than this, approximately 30 minutes before incision. A repeat dose should be given approximately 3 hours later in lengthy operations.

For skin preparation, scrubbing with a sponge saturated with 70% alcohol is used to remove grease, desquamated skin, dirt, and debri. After this dries, paint the skin with DuraPrep®. Wait until it dries completely and then apply Ioban®. Press firmly over the site of the incision since this has a pressure-sensitive adhesive, and lifting of the Ioban® from the skin edge will result in an increased incidence in wound infection. Evacuate all trapped bubbles. If the Ioban® adheres well to the skin edges, there is no possibility of contamination from the skin.

Make the incision from the xiphoid to just above the umbilicus. Incise the subcutaneous fat with a knife rather than electrocautery to minimize tissue damage. Electrocautery can be used to spot coagulate bleeders. Make the fascial incision in the center of the linea alba without cleaning off any of the attached fat.

Closure of the fascia at the end of the operation should be done with a running #2 Prolene starting at each end and tying the sutures together somewhere in the middle with six square tightly tied knots. The ends of the suture should be cut short to avoid sharp points. To avoid the “cheese cloth” type of hernias, the bites into the fascia should be placed approximately 1 cm from the edge and 1 cm apart, making certain not to pull the sutures excessively tight. It might seem intuitive to take larger bites into the fascia, but this actually increases tension at spots where the fascia is not as strong and promotes the development of the “cheese cloth” hernias.

The deep subcutaneous tissue is closed partly with a running suture of 3-0 Vicryl using a very large curved needle (XLH) so that the space, including the Scarpa’s fascia and down to the midline fascia, is basically obliterated. The skin is closed with a subcuticular stitch using 3-0 PDS starting at each end and burying the knot in the middle using vertical rather than horizontal dermal stitches. Steri-strips are applied to the wound immediately after closure.

Before dermal closure, place a drain from a Hemovac® into the subcutaneous space. After skin closure, infuse 20 to 80 mL of solution of gentamicin (320 μg/mL) or kanamycin (1000 μg/mL) and attach the tubing to the reservoir but do not activate suction, leaving the fluid to remain in the wound for 2 hours before removal by activation of the collection device. This allows for diffusion of the antibiotic into the tissues and will reduce the incidence of wound infections to <0.5%. The drain can be removed on the second postoperative day just before discharge.

Some surgeons use a left subcostal approach, but this may prevent doing a cholecystectomy, and it is important to do a thorough intraabdominal examination with the initial procedure.

If the patient has an umbilical or epigastric hernia, it should be repaired as part of the initial closure since this could be a site for a postoperative small bowel incarceration, and repair usually prevents the need for re-operation.

Cholecystectomy

A concurrent cholecystectomy may be performed if the patient has not already had one. This adds 20 to 30 minutes to the procedure, but is a safe cost-effective means to prevent the need for a subsequent cholecystectomy. An intraoperative cholangiogram is done if there are relative indications for doing so. It is important to address this since access to the duodenum by EGD is obviously not possible after GBP.

If common duct exploration is done, placement of a T-tube should be done using an additional length of the T-tube intraabdominally since it can be dislodged by excessive tension when the patient stands up because of an excessive abdominal wall thickness.

Gastric Bypass

Creation of the Enteroenterostomy

Before performing the enteroenterostomy, the entire bowel should be examined and adhesions from prior operations lysed using appropriate treatment for any pathologic lesions that are found (e.g., ovarian mass).

Next, the length of the alimentary, biliopancreatic and common channels limbs should be determined. A frequent choice is to make the biliopancreatic limb 80 to 100 cm and the alimentary limb 150 cm. This is sometimes modified if the mesentery is short, making it difficult to bring the end of the alimentary limb to the gastric pouch without tension. In our program, we have chosen to modify the length of the alimentary and biliopancreatic limbs to be longer as the patient’s weight increases (e.g., each limb 0.5 cm × patient’s weight in pounds). For a patient weighing 400 pounds, the alimentary limb would be 200 cm and the biliopancreatic limb 200 cm; for a patient weighing 500 pounds, both the biliopancreatic limb and alimentary limb would be 250 cm.

Once the site is selected, the bowel is divided with a GIA-55 stapler and the cut ends oversewn with 3-0 Prolene. The suture on the antimesenteric side of the closure of the distal limb is cut long so that it can be identified later as the proximal end of the alimentary limb.

The mesentery is then divided.

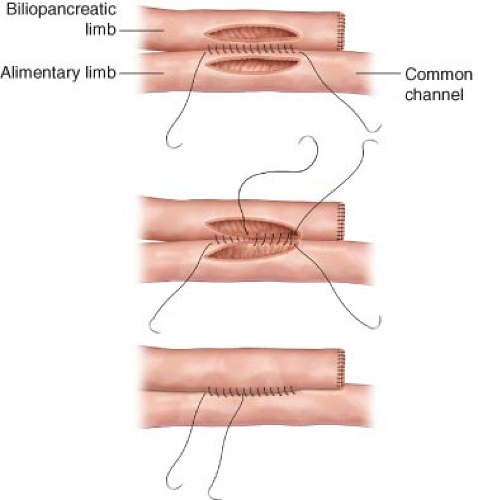

A side-to-side anastomosis is then made with the bilio-pancreatic limb using a hand-sewn anastomosis using an inner layer of 3-0 Maxon® and outer layer of 3-0 Prolene® (Fig. 28.1). After completion of the posterior outer suture line, opposing enterotomies are made with an electrocautery to form an orifice of approximately 5 cm. It is important

not to make the orifice too large as this can result in a sack that does not empty well and is prone to bacterial overgrowth. The inner suture line is placed and continued anteriorly so that there is only one knot, using a running lock stitch. This type of anastomosis is extremely stable. In approximately 1,000 patients, there has been only one patient who has had postoperative bleeding from this site, and there have been no leaks or obstructions. The mesenteric defect is closed with interrupted 2-0 silk sutures.

Creation of the Pouch

First, make sure the alimentary limb will reach the pouch without tension. Then, the upper fundus and cardio-esophageal junction are mobilized by blunt dissection behind the upper part of the stomach. The peritoneum on the right side can then be incised to mobilize circumferentially. Care should be used not to enter the stomach by keeping the blunt dissection posteriorly.

Bring an 18 French urinary catheter behind the stomach with the open end toward the right. Then thread the catheter onto the posterior anvil of a TA90B stapler and bring the anvil behind the stomach using the catheter as a guide (Fig. 28.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree