Online Chapter 1

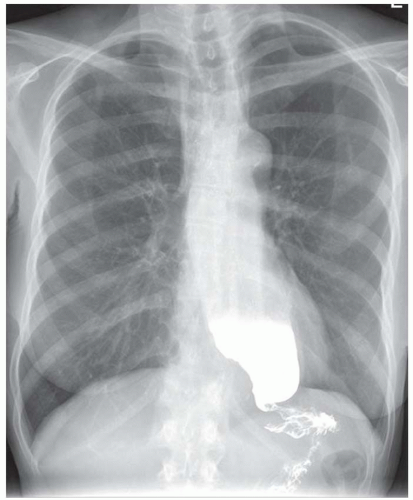

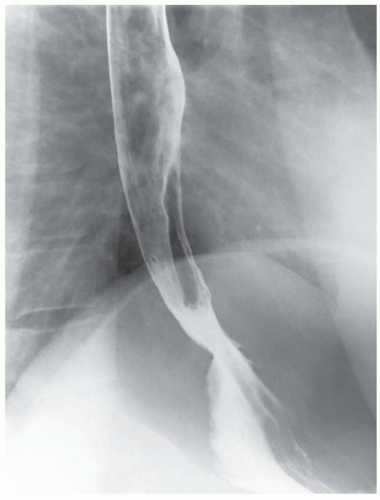

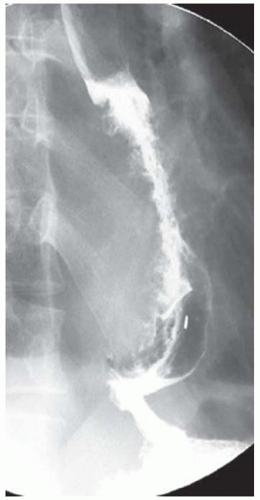

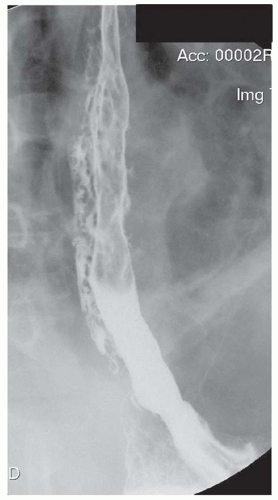

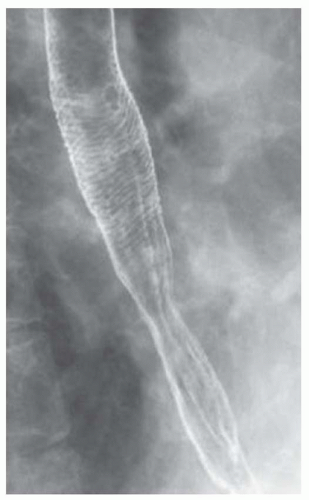

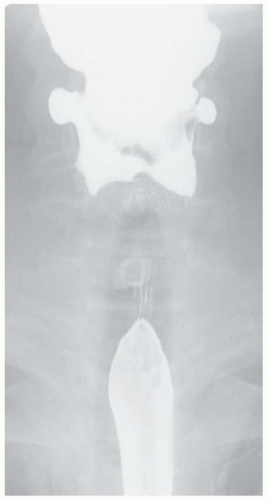

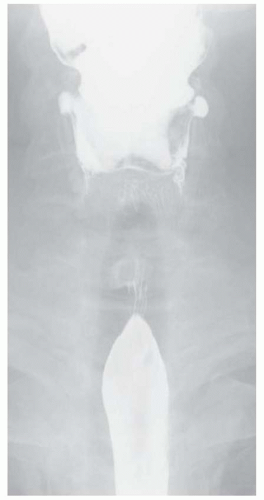

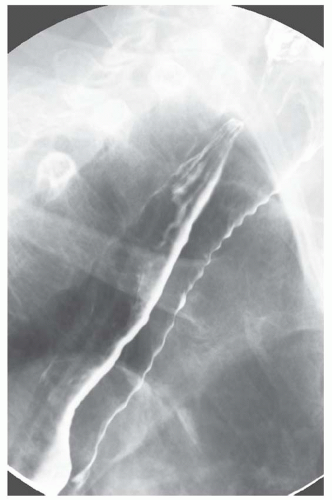

CASE 1.1 CLINICAL HISTORY 46-year-old man with dysphagia.

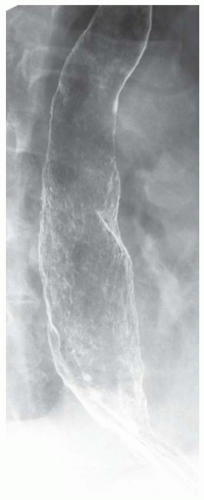

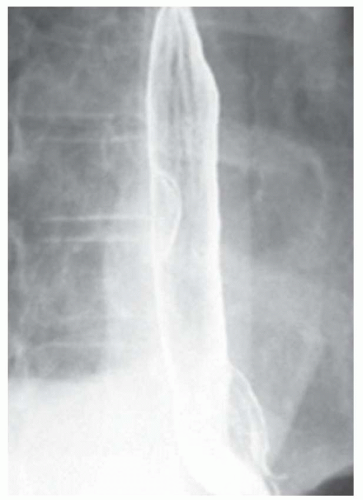

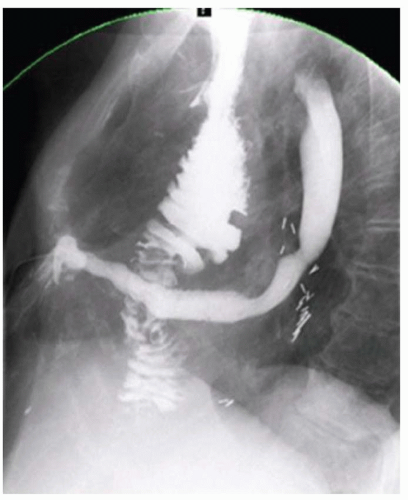

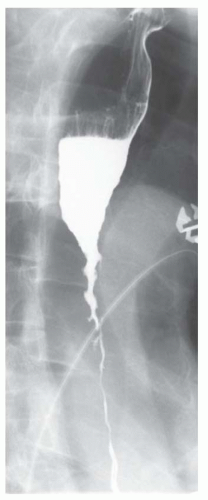

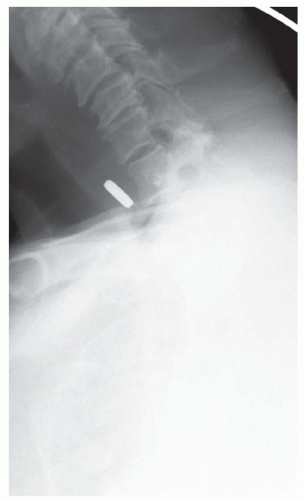

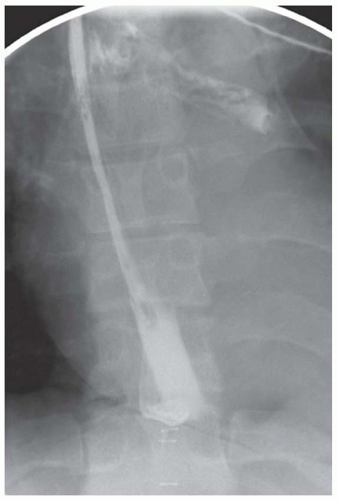

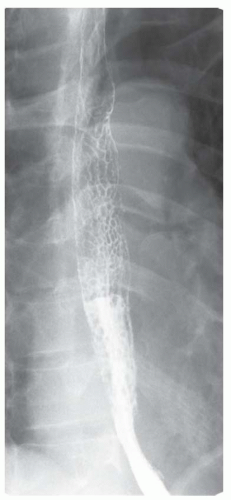

FINDINGS Frontal and lateral radiographs (A, B) obtained at the conclusion of a barium swallow demonstrate a dilated, patulous esophagus. Distally, the esophagus is narrowed. At real-time imaging, ingested contrast material appeared to slide down the walls of the esophagus without any real assistance from primary or secondary peristaltic waves. Ingested contrast material pooled in the distal esophagus and eventually slowly emptied into the stomach. At the conclusion of the study, a moderate amount of contrast material remained in the esophagus as seen in these radiographs.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Achalasia, distal esophageal cancer.

DIAGNOSIS Achalasia.

DISCUSSION Achalasia is a primary esophageal motility disorder characterized by the failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax. At barium swallow, the characteristic “bird-beak” or narrowed appearance of the distal esophagus reflects this failure of the distal esophageal sphincter to relax. At initial presentation, all patients in whom achalasia is suspected should undergo upper endos-copy to exclude a distal esophageal mass causing a pseudoachalasia appearance.

Early in the disease process, achalasia may be misdiagnosed as an isolated distal esophageal stricture. As the disease progresses, increasingly impaired peristalsis is noted due to progressively impaired function of neural networks in the smooth muscle of the distal esophagus. Large-volume food debris may be present in the esophagus at the time of barium swallow even if the patient has not consumed any food by mouth for many hours prior to the study.

A variety of treatment options are available for patients with achalasia (please see Question 2). At some centers, timed barium swallow is performed as a way to evaluate esophageal clearance pre- and post-treatment. Patients ingest 100 to 200 mL of contrast material (volume ingested should be recorded and repeated in follow-up studies), and upright left posterior oblique images are obtained 1, 2, and 5 minutes post contrast ingestion. The percentage of contrast material cleared at 5 minutes is estimated by comparing the computed area of contrast material (width × height of esophageal contrast column) in the 1- and 5-minute films.

Questions for Further Thought

1. What is the etiology of achalasia?

View Answer

1. The etiology of achalasia is unknown. Theories include a genetic, autoimmune, or infectious trigger that incites an inflammatory process that damages the neural networks in esophageal smooth muscle.

2. What are current treatment options for achalasia patients?

View Answer

2. At the present time there is no way to reverse the nerve damage that produces achalasia. Current treatments are aimed at relieving symptoms. Myotomy (via open or laparoscopic approach) or endoscopic balloon dilatation may be performed to dilate a distal esophageal stricture. Botulinum toxin injection via endoscopy can relax the lower esophageal sphincter and provide short-term symptom palliation. Medical management including calcium channel blockers or long-acting nitrates can provide short-term symptomatic relief because of their muscle relaxation properties. The last line treatment option for patients with a megaesophagus who do not respond to other treatments is esophagectomy.

Reporting Requirements

1. Suggest the diagnosis of achalasia.

2. Recommend esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) at initial presentation to rule out an obstructing mass resulting in pseudoachalasia.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. At initial presentation, achalasia can be difficult to distinguish from a distal esophageal malignant stricture.

2. At initial presentation, all patients with suspected achalasia based on barium swallow should undergo upper endoscopy to exclude a distal esophageal mass resulting in pseudoachalasia.

Answers

1. The etiology of achalasia is unknown. Theories include a genetic, autoimmune, or infectious trigger that incites an inflammatory process that damages the neural networks in esophageal smooth muscle.

2. At the present time there is no way to reverse the nerve damage that produces achalasia. Current treatments are aimed at relieving symptoms. Myotomy (via open or laparoscopic approach) or endoscopic balloon dilatation may be performed to dilate a distal esophageal stricture. Botulinum toxin injection via endoscopy can relax the lower esophageal sphincter and provide short-term symptom palliation. Medical management including calcium channel blockers or long-acting nitrates can provide short-term symptomatic relief because of their muscle relaxation properties. The last line treatment option for patients with a megaesophagus who do not respond to other treatments is esophagectomy.

REFERENCES

1. de Oliveira JMA, Birgisson S, Doinoff C, et al. Timed barium swallow: a simple technique for evaluating esophageal emptying in patients with achalasia. Am J Roentgenol 1997;169: 473-479.

2. Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:3406-3412.

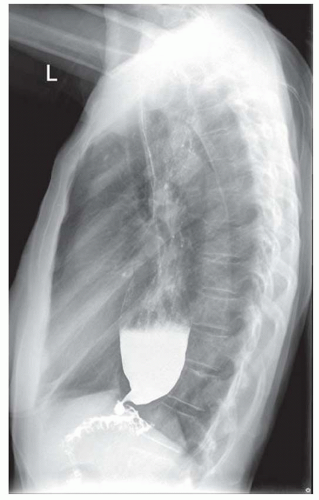

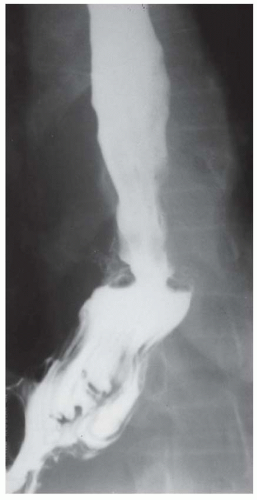

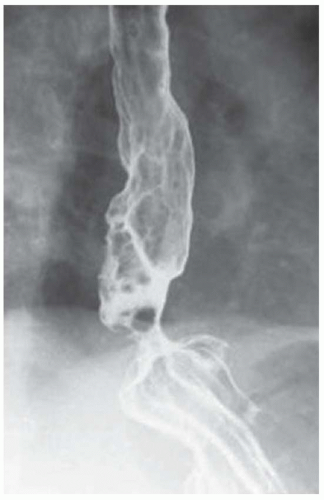

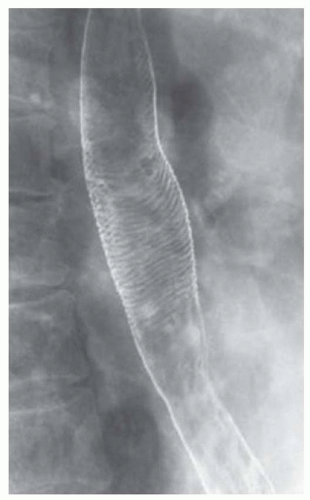

CASE 1.2 CLINICAL HISTORY 75-year-old woman with dysphagia.

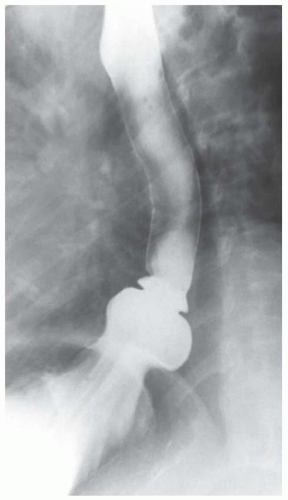

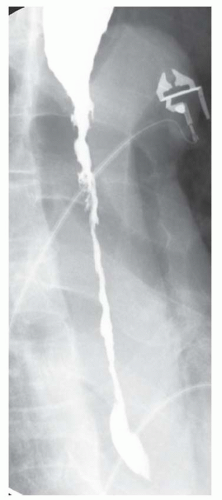

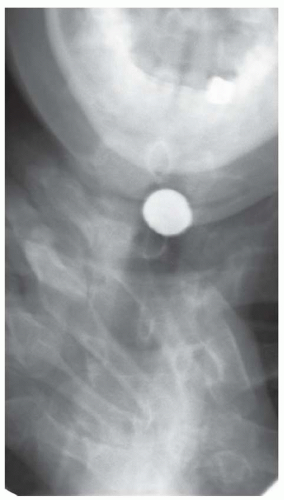

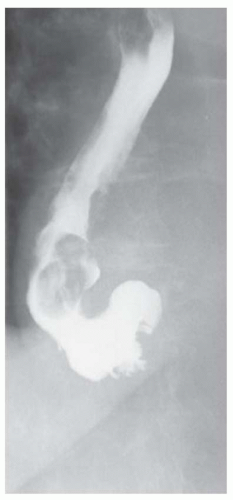

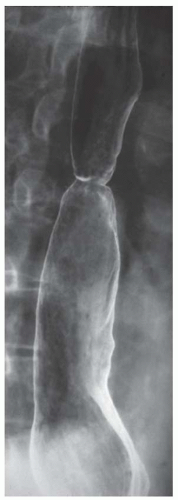

FINDINGS Barium swallow demonstrates intermittent, non-peristaltic esophageal contractions.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Diffuse esophageal spasm (“corkscrew esophagus”), nutcracker esophagus, presbyesophagus.

DIAGNOSIS Diffuse esophageal spasm.

DISCUSSION Diffuse esophageal spasm refers to simultaneous, nonperistaltic contractions of multiple portions of the esophagus resulting in a corkscrew appearance at barium swallow as demonstrated above. Chest pain or dysphagia may be the primary symptom in patients with diffuse esophageal spasm.

By comparison, barium swallow is often normal in patients with nutcracker esophagus. Nutcracker esophagus is a motility disorder diagnosed at manometry. Isolated high-pressure esophageal contractions greater than 180 mmHg are diagnostic of nutcracker esophagus. Such high-pressure recordings are generally recorded in a portion of the esophagus rather than the entire esophagus as with diffuse esophageal spasm. Chest pain or dysphagia also may be the primary symptom in patients with nutcracker esophagus.

Presbyesophagus refers to abnormal esophageal motility, which is more frequently seen in older patients. “Presby-” is a prefix that comes from the Greek word for old age and is present in a number of medical terms, including presbyopia (age-related difficulty focusing the eye on near objects) and presbycusis (age-related hearing loss). Age-related changes in esophageal motility include a weakened or absent primary peristaltic wave, often with tertiary contractions. These age-related changes may be asymptomatic or result in dysphagia.

Questions for Further Thought

1. Define primary, secondary, and tertiary peristalsis.

View Answer

1. The primary peristaltic wave is triggered by swallowing and propels the food or liquid bolus down the esophagus. The secondary peristaltic wave is triggered by stretch receptors and propels the remaining bolus not cleared by the primary peristaltic wave. Tertiary contractions are uncoordinated, nonpropulsive contractions seen with increasing frequency in elderly patients.

2. Define primary motility disorder and secondary motility disorder.

View Answer

2. Primary motility disorders are defined as isolated esophageal abnormalities of primary, secondary, and/or tertiary peristalsis (e.g., achalasia). Secondary motility disorders are those that are related to other illness (e.g., diabetes or scleroderma). A motility disorder related to an obstructing or near-obstructing esophageal malignancy is usually referred to as a secondary motility disorder.

Reporting Requirement

1. Report the presence of intermittent diffuse esophageal spasm.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. Report whether episodes of diffuse esophageal spasm correlated with patient symptoms of chest pain or dysphagia during the study.

Answers

1. The primary peristaltic wave is triggered by swallowing and propels the food or liquid bolus down the esophagus. The secondary peristaltic wave is triggered by stretch receptors and propels the remaining bolus not cleared by the primary peristaltic wave. Tertiary contractions are uncoordinated, nonpropulsive contractions seen with increasing frequency in elderly patients.

2. Primary motility disorders are defined as isolated esophageal abnormalities of primary, secondary, and/or tertiary peristalsis (e.g., achalasia). Secondary motility disorders are those that are related to other illness (e.g., diabetes or scleroderma). A motility disorder related to an obstructing or near-obstructing esophageal malignancy is usually referred to as a secondary motility disorder.

REFERENCES

1. Prabhakar A, Levine MS, Rubesin S, Laufer I, Katzka D. Relationship between diffuse esophageal spasm and lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction on barium studies and manometry in 14 patients. Am J Roentgenol 2004;183:409-413.

2. Tack J, Vantrappen G. The aging oesophagus. Gut 1997;41: 422-424.

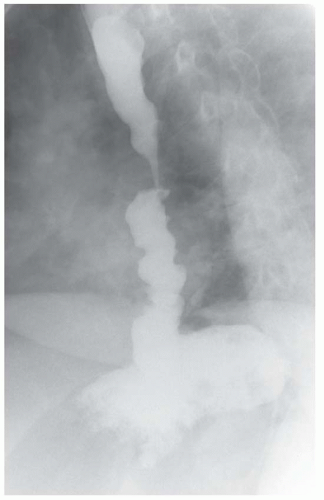

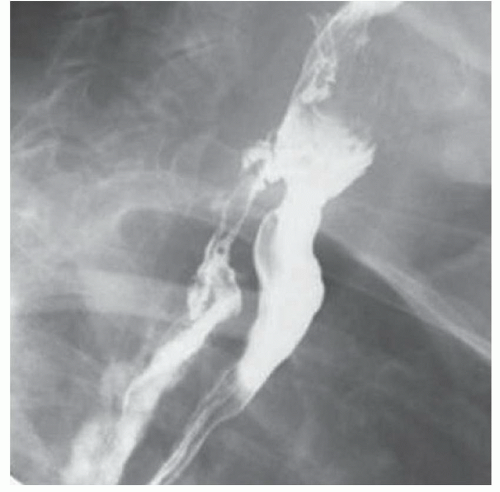

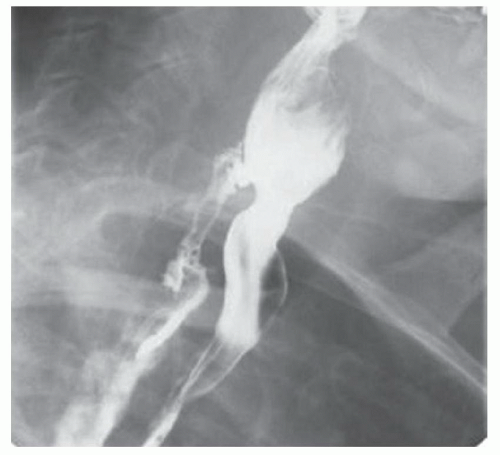

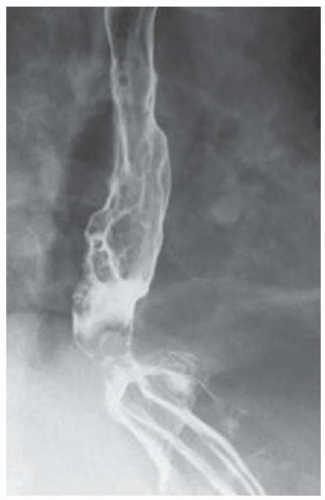

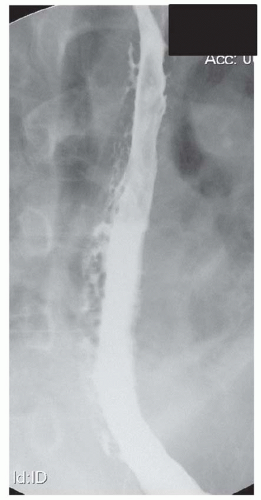

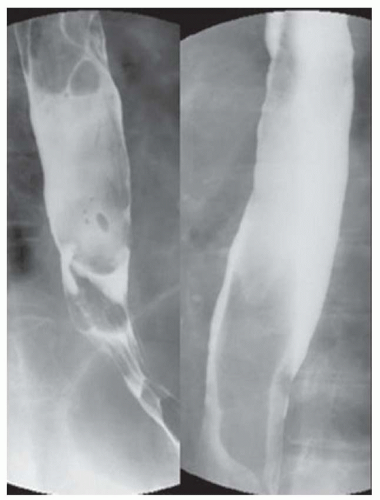

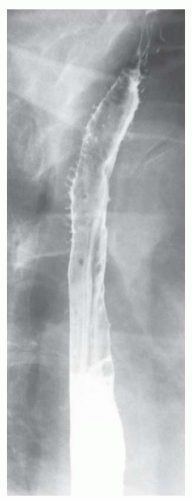

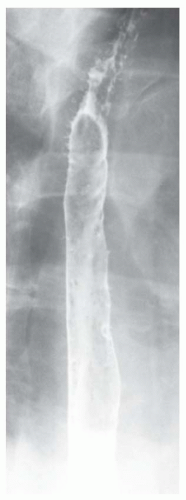

CASE 1.3 CLINICAL HISTORY 55-year-old man with dysphagia.

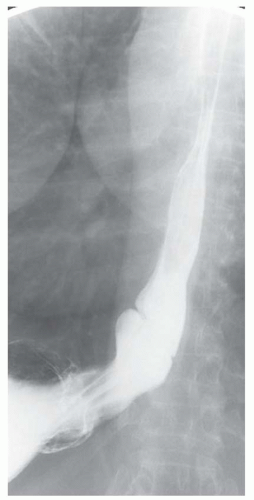

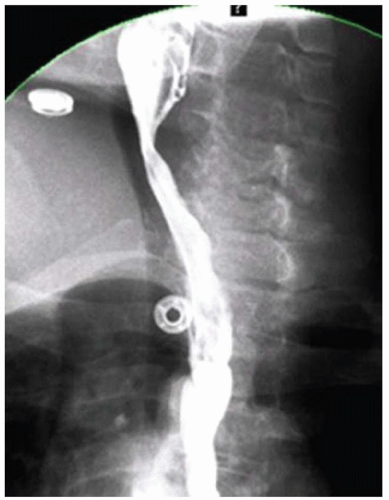

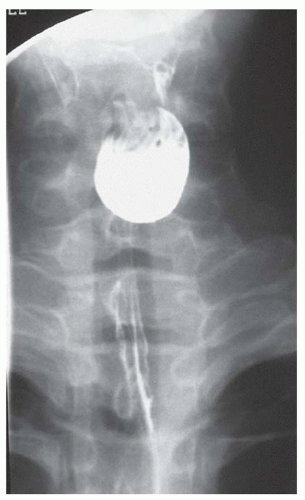

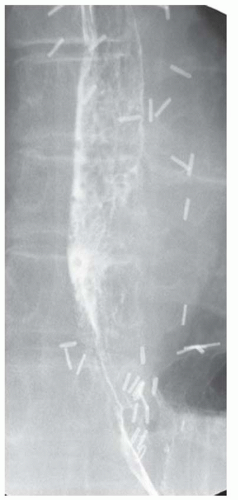

FINDINGS Air-contrast barium swallow (A, B) demonstrates linear, tubular filling defects running parallel to the longitudinal axis of the esophagus. These structures were intermittently visible during the barium swallow.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Normal longitudinal folds, varices, varicoid esophageal cancer.

DIAGNOSIS Varices.

DISCUSSION Esophageal varices are dilated submucosal veins within the wall of the esophagus. Varices most commonly occur in patients with portal hypertension and are prone to bleeding. Bleeding from esophageal varices is the cause of death in approximately one-third of patients with chronic liver disease and portal hypertension.

Esophageal varices are graded based on their appearance at endoscopy. Grade 1 varices are small, straight varices. Grade 2 varices are large, tortuous varices that occupy less than one-third of the esophageal lumen. Grade 3 varices are large, tortuous varices that occupy more than one-third of the lumen.

Fluoroscopy is a relatively insensitive test for the demonstration of varices. Meticulous attention to technique is necessary to demonstrate varices as they may be intermittently visible during barium studies as in the above case. For example, full-column barium may efface varices rendering them invisible. Varices also may change caliber depending on intrathoracic pressure. Placing the patient in a prone, right anterior oblique position can aid in the demonstration of varices by (1) increasing variceal distention due to gravity effects and (2) improving mucosal coating by slowing the transit of barium. Valsalva maneuver may increase the conspicuity of varices. Single small sips of barium may improve detection of varices as repeated peristalsis may efface varices.

Varicoid esophageal cancer is usually more irregular in appearance and a more fixed abnormality when compared with esophageal varices. However, when in doubt contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is a noninvasive way to rule in or rule out most varices.

The collapsed esophagus often demonstrates longitudinal folds. However, these folds generally run the entire length

of the esophagus and can be distinguished from varices that are usually isolated to the upper third or lower third of the esophagus (see below).

of the esophagus and can be distinguished from varices that are usually isolated to the upper third or lower third of the esophagus (see below).

Questions for Further Thought

1. Define uphill varix.

View Answer

1. Uphill varices occur in patients with portal hypertension and are usually confined to the lower third of the esophagus. These collateral pathways allow blood to bypass the liver and return to the heart via enlarged esophageal collateral vessels and the superior vena cava.

2. Define downhill varix.

View Answer

2. Downhill varices occur in patients with superior vena cava obstruction and are usually located in the upper third or middle third of the esophagus. These dilated esophageal collateral vessels allow blood to return to the heart via the portal venous system and the inferior vena cava.

Reporting Requirement

1. Report the presence of probable esophageal varices along the distal esophagus.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. Endoscopy is the gold standard test for diagnosing and grading varices.

2. CT and MR are more sensitive than barium swallow for the identification of varices.

Answers

1. Uphill varices occur in patients with portal hypertension and are usually confined to the lower third of the esophagus. These collateral pathways allow blood to bypass the liver and return to the heart via enlarged esophageal collateral vessels and the superior vena cava.

2. Downhill varices occur in patients with superior vena cava obstruction and are usually located in the upper third or middle third of the esophagus. These dilated esophageal collateral vessels allow blood to return to the heart via the portal venous system and the inferior vena cava.

REFERENCES

1. Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Diseases of the esophagus: diagnosis with esophagography. Radiology 2005;237:414-427.

2. de Franchis R, Primignani M. Natural history of portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis 2001;5:645-663.

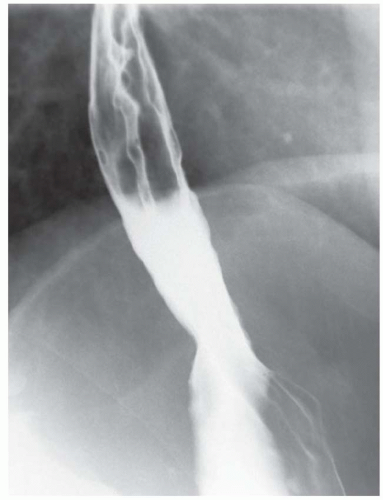

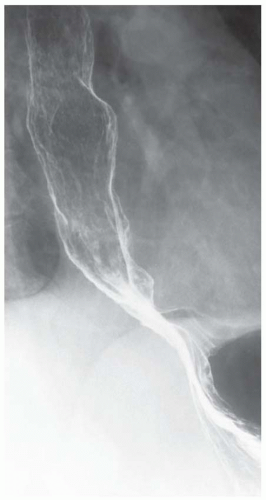

CASE 1.4 CLINICAL HISTORY 67-year-old man with dysphagia.

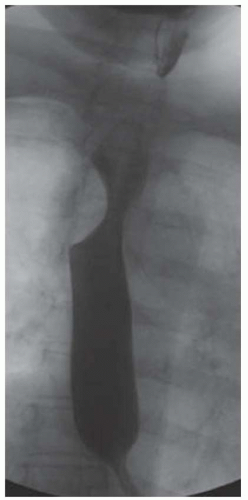

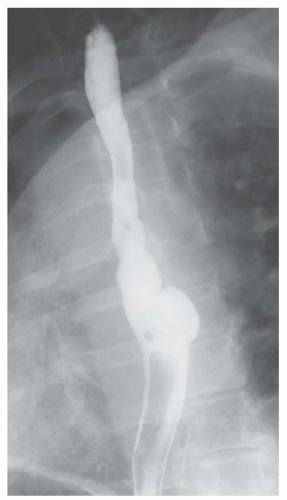

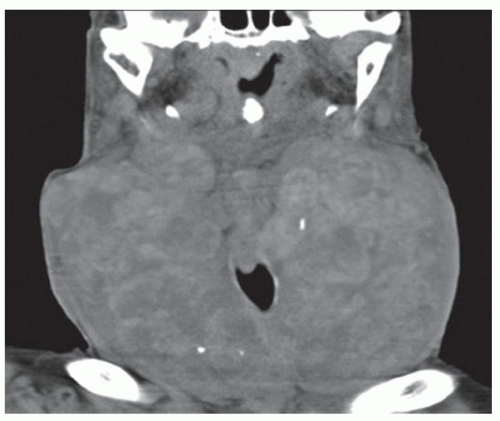

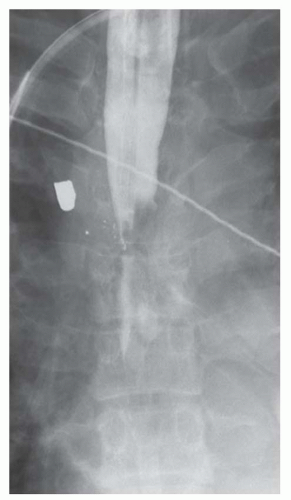

FINDINGS Image from a barium swallow demonstrates an approximately 5 cm in length area of circumferential narrowing of the distal esophagus extending to the level of the esophagogastric junction and also involving the proximal stomach. The esophageal mucosa is smooth.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Esophageal carcinoma, submucosal mass, extrinsic compression.

DIAGNOSIS Submucosal mass (lymphoma based on EUS-guided biopsy).

DISCUSSION The smooth appearance of the mucosa in this case makes esophageal carcinoma unlikely. The differential diagnosis in this case is therefore narrowed to a submucosal mass or an area of extrinsic compression. In the present case, the patient underwent EUS with tissue sampling, and a diagnosis of esophageal lymphoma (a submucosal process) was confirmed. CT imaging to evaluate for an extraesophageal mass resulting in extrinsic compression would also have been an appropriate next step.

Primary esophageal lymphoma is very rare. The esophagus is the least commonly involved portion of the GI tract in patients with extranodal GI tract lymphoma. The majority of lymphomas involving the GI tract are non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Esophageal lymphoid tissue is located in both the mucosal layer of the esophagus and the submucosal layer. Primary lymphomatous involvement of the esophagus therefore may manifest as an area of ulceration, a polypoid mass, or as an area of submucosal nodularity or thickening as in the above case.

Question for Further Thought

1. What location in the GI tract is most commonly involved by extranodal lymphoma?

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the location and extent of the abnormality.

2. Suggest EUS with possible tissue sampling or CT for further evaluation.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. This patient has an abnormal, mass-like area of distal esophageal narrowing which is suspicious for malignancy.

2. EUS with tissue sampling should be considered to establish the diagnosis.

3. Alternatively, CT could be performed to evaluate for a mediastinal mass resulting in extrinsic compression.

Answer

1. The stomach is the most common location for extranodal primary GI lymphoma.

REFERENCE

1. Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Pantongrag-Brown L, Buck JL, Herlinger H. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: radiographic findings. Am J Roentgenol 1997;168:165-172.

CASE 1.5 CLINICAL HISTORY 65-year-old woman, history withheld.

FINDINGS Images (A, B) from a swallow study demonstrate fixed narrowing of the cervical esophagus just above the thoracic inlet. Just above this level of narrowing, contrast material is seen extending posteriorly from the esophagus as well as within the esophageal lumen.

DIAGNOSIS Esophageal perforation.

DISCUSSION This patient sustained an esophageal perforation during attempted endoscopic stricture dilation. Clues to the diagnosis of an esophageal perforation include (1) continued accumulation of contrast material at the site of perforation and (2) absence of peristalsis of the leaked contrast material.

If esophageal perforation is suspected, water-soluble contrast material should initially be administered as water-soluble contrast material will be resorbed if it leaks into the mediastinum. By comparison, leaked barium will not be resorbed and can result in a mediastinitis.

The water-soluble study was positive for leak in this patient. In situations where the initial swallows with water-soluble contrast material are negative and a large leak is excluded, the patient should then ingest barium. Barium is more conspicuous at fluoroscopy and may better demonstrate small leaks. Additionally, as barium is less foul-tasting, patients may be able to swallow larger gulps of barium thereby resulting in increased esophageal distention and better demonstration of a leak. The study should immediately be terminated as soon as any leaked barium is confidently identified.

Question for Further Thought

1. What contrast agent should be used in patients with suspected aspiration or a tracheoesophageal fistula?

View Answer

1. Small sips of barium should be used in patients with suspected aspiration or a tracheoesophageal fistula. Water-soluble contrast material should be avoided as aspiration of water-soluble contrast material can result in pneumonitis. If a patient is observed to aspirate barium, he/she should be instructed to cough up as much as possible as aspiration of large amounts of barium can also result in a severe pneumonitis, especially in debilitated elderly patients.

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the presence of a leak arising from the proximal cervical esophagus.

2. Directly communicate these findings to the treating physician.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. The location of the leak.

2. The subjective size of the leak.

3. If the patient has a drain in place, report whether the drain is adequately draining the leaked contrast material.

Answer

1. Small sips of barium should be used in patients with suspected aspiration or a tracheoesophageal fistula. Water-soluble contrast material should be avoided as aspiration of water-soluble contrast material can result in pneumonitis. If a patient is observed to aspirate barium, he/she should be instructed to cough up as much as possible as aspiration of large amounts of barium can also result in a severe pneumonitis, especially in debilitated elderly patients.

REFERENCE

1. Franquet T, Gimenez A, Roson N, Torrubia S, Sabate JM, Perez C. Aspiration diseases: findings, pitfalls, and differential diagnosis. Radiographics 2000;20:873-685.

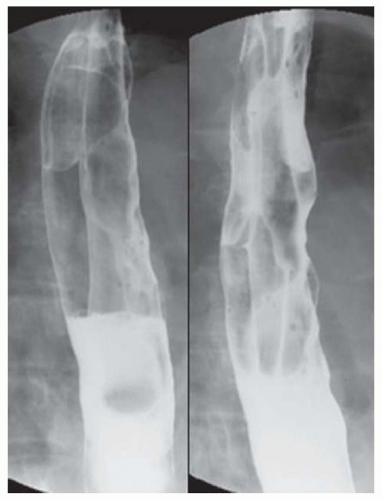

CASE 1.6 CLINICAL HISTORY 66-year-old woman with dysphagia.

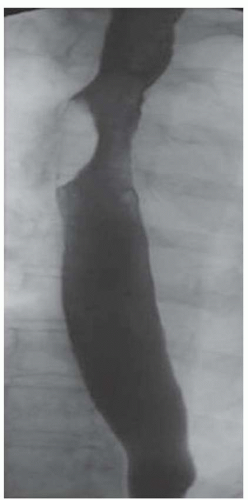

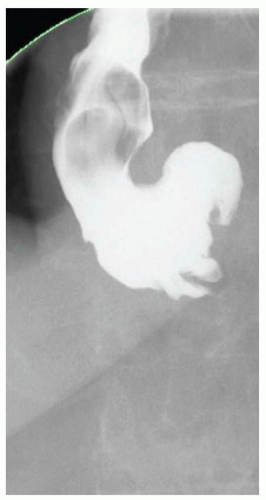

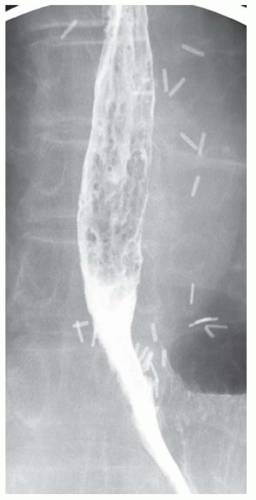

FINDINGS Air-contrast barium swallow demonstrates a large, approximately 7-cm segmental area of luminal narrowing and mucosal irregularity involving the distal third of the esophagus (A, B).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Neoplasm, severe inflammation caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

DIAGNOSIS Neoplasm (adenocarcinoma).

DISCUSSION An estimated 17,990 new cases of esophageal cancer were diagnosed in the United States in 2012, and 15,210 individuals died from the disease. In the United States, adenocarcinoma is the most common esophageal cancer subtype, the distal esophagus is the most common location, and GERD is the most common risk factor. Worldwide, squamous cell carcinoma is the most common subtype, the upper esophagus is the most common location, and alcohol and tobacco use are the major risk factors.

GERD results in chronic esophageal irritation and inflammation which can progress to esophageal metaplasia (also known as Barrett esophagus) and eventually to esophageal cancer. Patients with esophageal cancer often present with dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and odynophagia (painful swallowing). Raspy cough may also occur if the tumor involves the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Tumors are generally large by the time they become symptomatic which accounts for the poor prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer. Additionally, the esophagus lacks a serosal layer which normally serves as a barrier to extension of disease elsewhere in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Chemoradiation followed by esophagogastrectomy is the usual treatment for distal esophageal cancers. Palliative treatment includes the placement of metallic stents to palliate obstructing lesions.

The hallmark of esophageal malignancy at barium swallow is mucosal irregularity. Mucosal irregularity distinguishes mucosal lesions from submucosal and extrinsic lesions. Compare the mucosal irregularity seen in this case with the predominantly smooth appearance of the mucosa seen with the submucosal masses in other cases in this volume. Esophageal cancers can also appear as plaque-like or polypoid masses.

Question for Further Thought

1. What methods are used to stage esophageal cancer?

View Answer

1. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is used to determine the local extent of disease and sometimes nodal disease. CT and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT are also used to evaluate for nodal disease and to evaluate for metastases (e.g., liver and lung).

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the location of the abnormality.

2. Recommend EGD and tissue sampling to determine the diagnosis.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. This patient has a large esophageal mass that is highly suspicious for malignancy.

2. Further evaluation is required with tissue sampling.

3. Whether the mass is obstructing based on the transit of liquid barium and the 12.5-mm compressed barium tablet.

Answer

1. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is used to determine the local extent of disease and sometimes nodal disease. CT and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT are also used to evaluate for nodal disease and to evaluate for metastases (e.g., liver and lung).

REFERENCES

1. www.cancer.gov. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyren O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 1999;340:825-831.

3. Shaheen NJ, Richter JE. Barrett’s oesophagus. Lancet 2009;373: 850-861.

CASE 1.7 CLINICAL HISTORY 53-year-old woman with dysphagia.

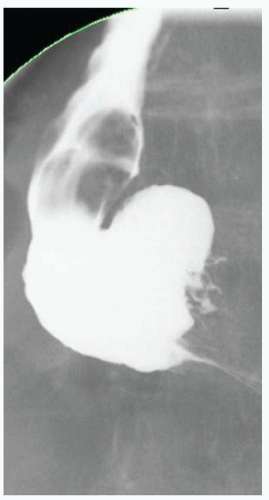

FINDINGS Air-contrast barium swallow (A, B) demonstrates an approximately 4-cm segmental plaque-like area of wall thickening and mucosal irregularity involving the distal esophagus.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Neoplasm, severe inflammation caused by GERD.

DIAGNOSIS Neoplasm (adenocarcinoma).

DISCUSSION The mucosal irregularity seen in this case indicates that this is a mucosal process. This abnormality is compatible with esophageal cancer, and EGD is needed for tissue confirmation. Distal esophageal cancers are most commonly adenocarcinomas. GERD is a major risk factor.

Staging of esophageal cancer often involves endoscopy, CT or PET/CT studies to evaluate local disease extent, nodal stations, and for the presence of distant metastatic disease. Since the esophagus lacks a serosal surface, there is not a significant barrier to prevent esophageal malignancies from directly extending into adjacent structures including the tracheobronchial tree and lung.

The esophagus contains an extensive lymphatic system with bidirectional flow and is unusual in its lymphatic drainage as the esophagus is drained by nodal stations located both above and below the diaphragm. The lymphatics of the upper third of the esophagus, in general, drain craniad with involvement of nodal stations including internal jugular and supraclavicular stations. The lymphatics of the distal third of the esophagus, in general, drain below the diaphragm to involve gastrohepatic ligament and celiac lymph nodes. However, because of bidirectional flow in the extensive esophageal lymphatic plexus distal cancers may result in supraclavicular lymph node disease and vice versa.

Location of hematogeneous metastases in decreasing order of frequency are as follows: liver, lungs, bones, adrenal glands, kidneys, and brain.

Questions for Further Thought

1. Describe the different morphologies of esophageal cancer seen at barium swallow.

View Answer

1. Esophageal cancers may appear as areas of mucosal irregularity, plaque-like lesions, or polypoid lesions.

2. What modality is recommended to determine the depth of tumor invasion?

View Answer

2. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is used to determine the depth of tumor invasion and is often used to evaluate for disease in regional lymph nodes.

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the location of the abnormality.

2. Recommend EGD and tissue sampling to determine the diagnosis.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. This patient has a large esophageal mass that is highly suspicious for malignancy.

2. Further evaluation is required with tissue sampling.

Answers

1. Esophageal cancers may appear as areas of mucosal irregularity, plaque-like lesions, or polypoid lesions.

2. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is used to determine the depth of tumor invasion and is often used to evaluate for disease in regional lymph nodes.

REFERENCES

1. www.cancer.gov. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Diseases of the esophagus: diagnosis with esophagography. Radiology 2005;237:414-427.

3. Sharma A, Fidias P, Hayman LA, Loomis SL, Taber KH, Aquino SL. Patterns of lymphadenopathy in thoracic malignancies. Radiographics 2004;24:419-434.

CASE 1.8 CLINICAL HISTORY 68-year-old man with history of GERD.

FINDINGS Air-contrast barium swallow (A, B) demonstrates an abnormal appearance of the distal esophageal mucosa with rounded and linear crevices filled with contrast material.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Barrett esophagus, esophageal adenocarcinoma.

DIAGNOSIS Barrett esophagus.

DISCUSSION At fluoroscopy, a reticular mucosal pattern with barium-filling thin grooves or crevices is a highly specific but insensitive sign of Barrett esophagus. Barrett esophagus is defined as metaplasia with columnar epithelium replacing the usual esophageal squamous epithelium. The squamocolumnar junction is displaced proximally in patients with Barrett esophagus. Diagnosis is made based on mucosal biopsies at EGD.

Barrett esophagus is considered to be a premalignant condition. This abnormality is found in approximately 10% to 15% of adults with GERD who undergo endoscopy. Barrett esophagus is found in the majority of patients with esophageal and gastroesophageal cancers in the United States.

Most major GI societies recommend endoscopic surveillance of patients with Barrett esophagus at 1- to 3-year intervals to include detailed inspection of the esophageal mucosa and systematic biopsies. Treatment of Barrett esophagus includes medical management of GERD and antireflux surgery (e.g., hiatal hernia reduction and Nissen fundoplication) for patients who do not respond to medical management.

Barrett esophagus is named after Norman Barrett (1903 to 1979), a thoracic surgeon who described the condition in 1950.

Questions for Further Thought

1. What percentage of patients with reflux esophagitis develop Barrett esophagus?

View Answer

1. Approximately 10% of patients with reflux esophagitis will develop Barrett esophagus.

2. What percentage of patients with Barrett esophagus develop esophageal cancer?

View Answer

2. Roughly 0.5% of patients with Barrett esophagus per year develop esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the location and approximate length of disease.

2. Recommend that EGD and possibly tissue sampling be performed.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. EGD with tissue sampling is needed to confirm the diagnosis of Barrett esophagus.

Answers

1. Approximately 10% of patients with reflux esophagitis will develop Barrett esophagus.

2. Roughly 0.5% of patients with Barrett esophagus per year develop esophageal adenocarcinoma.

REFERENCES

1. Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Diseases of the esophagus: diagnosis with esophagography. Radiology 2005;237:414-427.

2. Sharma P. Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med 2009;361: 2548-2556.

CASE 1.9 CLINICAL HISTORY 63-year-old woman with dysphagia.

FINDINGS Fluoroscopic images from a single-contrast barium swallow (A, B) demonstrate mass effect on the proximal esophagus resulting in greater than 50% luminal narrowing. The area of mass effect has smooth margins. Coronal reformation from a noncontrast CT examination (C) demonstrates that the area of mass effect is from a calcified mediastinal lymph node.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF A SMOOTH, INTRAMURAL,\\ OR EXTRINSIC ESOPHAGEAL MASS Mediastinal lymph node, -omas (lipoma, leiomyoma, neuroma, fibroma, and neurofibroma), enteric duplication cyst, vascular impression.

DIAGNOSIS Calcified mediastinal lymph node.

DISCUSSION The smooth appearance of the mucosa in the above case is characteristic of a submucosal mass or extrinsic process. The appearance of such masses is that of a “marble under a rug.” When an intramural or extrinsic mass is suspected, CT is helpful to distinguish between lymph nodes (as in this case), other solid masses, vascular structures, or fatty masses such as lipomas.

Additionally, EUS rather than basic EGD is usually performed when tissue sampling of a submucosal or extrinsic process is necessary. With EUS the endoscopist can rule out any large vascular structures in the needle trajectory prior to sampling. Additionally, submucosal or extrinsic processes with an overlying smooth mucosa may not be detectable with basic EGD which provides direct visualization of the mucosal layer only.

Question for Further Thought

1. Define dysphagia, dysphasia, and odynophagia.

View Answer

1. Dysphagia = difficulty swallowing; dysphasia = difficulty using or understanding language due to a brain injury; odynophagia = painful swallowing.

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the area of narrowing and estimate the degree of luminal narrowing.

2. Suggest that the mass may be submucosal or extrinsic and suggest CT as the next step for diagnosis.

3. Report whether patient’s symptoms are reproduced when a 12.5-mm compressed barium tablet lodges at or traverses the area of narrowing.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. A submucosal or extrinsic mass is suspected.

2. Suggested next steps for diagnosis (e.g., CT for an extrinsic mass, EUS for a submucosal or extrinsic mass, and EGD for a mucosal mass).

Answer

1. Dysphagia = difficulty swallowing; dysphasia = difficulty using or understanding language due to a brain injury; odynophagia = painful swallowing.

REFERENCE

1. Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Diseases of the esophagus: diagnosis with esophagography. Radiology 2005;237:414-427.

CASE 1.10 CLINICAL HISTORY 57-year-old man with no known past medical history presents with chest pain.

FINDINGS Air-contrast barium swallow demonstrates extensive mucosal irregularity of the mid- and distal esophagus with extensive ulcerations (A, B).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Candida esophagitis, reflux esophagitis, Crohn esophagitis.

DIAGNOSIS Candida esophagitis.

DISCUSSION Candida albicans is the most common etiology of infectious esophagitis. The earliest manifestation of Candida esophagitis is esophageal dysmotility. The esophageal mucosa may appear normal at barium swallow early in the disease. As esophageal candidiasis worsens in severity, mucosal plaques may be visible followed by erosions and ulcerations. The above image is from a patient with very advanced disease. Crohn esophagitis could have a similar appearance, and EGD with biopsy was required to confirm the diagnosis.

Patients who develop candidiasis usually have a predisposing condition including immunosuppression (e.g., due to human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], steroids, chemotherapy, or transplant patients) or patients who have delayed esophageal emptying (e.g., due to esophageal strictures, scleroderma, or achalasia). Treatment of esophageal candidiasis is with fluconazole or itraconazole.

Question for Further Thought

1. What would be the next step to establish the diagnosis?

View Answer

1. Endoscopy with possible tissue sampling would be the next step to establish the diagnosis.

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the location of the mucosal abnormality.

2. Suggest EGD for further evaluation and possible tissue sampling.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. The imaging findings, though markedly abnormal, are nonspecific and EGD is needed for definitive diagnosis.

Answer

1. Endoscopy with possible tissue sampling would be the next step to establish the diagnosis.

REFERENCES

1. Roberts L, Gibbons R, Gibbons G, et al. Adult esophageal candidiasis: a radiographic spectrum. Radiographics 1987;7: 289-307.

2. Pappas PG, Rex JH, Sobel JD, et al. Guidelines for treatment of candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:161-189.

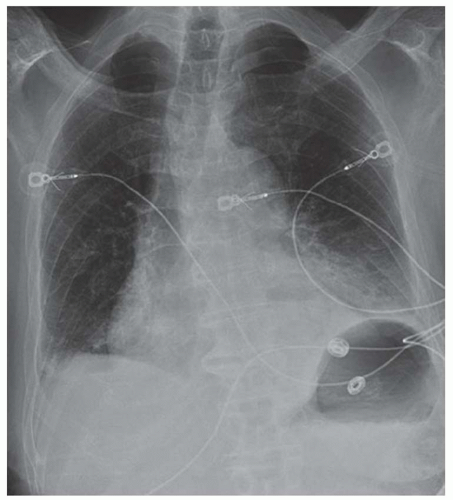

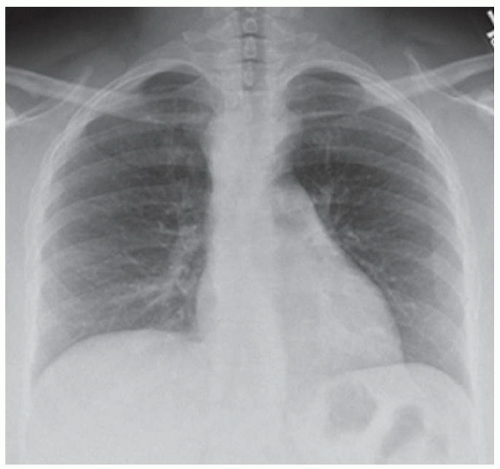

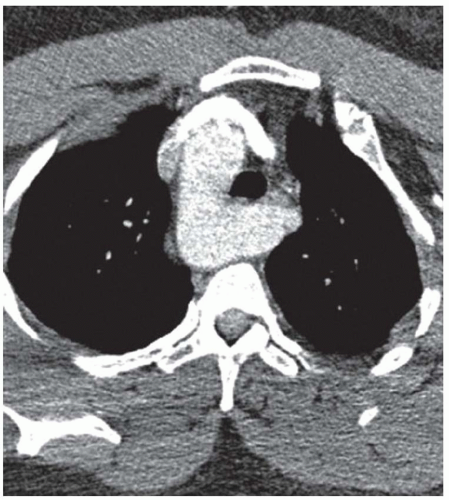

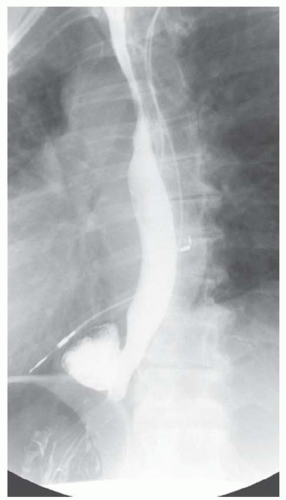

CASE 1.11 CLINICAL HISTORY 72-year-old man with chest pain following vomiting.

FINDINGS Initial chest radiograph (A) obtained in the emergency department demonstrates a retrocardiac air-fluid level. Differential diagnosis for this finding includes air-fluid level in a hiatal hernia versus in the pleural space due to esophageal rupture. A chest CT was performed (not shown) which demonstrated pneumomediastinum along with fluid and air in the left pleural space. Given CT findings and clinical history, there was a high level of concern for esophageal rupture. The patient underwent a swallow study which showed a somewhat linear collection of contrast material arising from and extending away from the left side of the distal esophagus (B).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Boerhaave syndrome, Mallory-Weiss tear.

DIAGNOSIS Boerhaave syndrome.

DISCUSSION Boerhaave syndrome is defined as rupture of the esophageal wall due to vomiting. A proposed mechanism is failure of normal relaxation of the cricopharyngeus muscle during vomiting leading to increased intraesophageal pressure and rupture. The resultant esophageal tear is usually oriented longitudinally, 1 to 4 cm in length, and located in the left lateral wall of the distal esophagus just proximal to the esophagogastric junction.

At plain film, pneumomediastinum, left pleural fluid, and subcutaneous emphysema may be seen. These same findings are also visible at chest CT. In the appropriate clinical setting, these findings are highly suggestive of Boerhaave syndrome. Esophagography is the definitive imaging test. Treatment includes surgical repair and antibiotic therapy. Untreated, mortality is assumed to be 100%. With treatment, mortality rates are reduced to <20%.

A Mallory-Weiss tear differs from Boerhaave syndrome as a Mallory-Weiss tear only involves the esophageal mucosa. In other words, with a Mallory-Weiss tear no esophageal leak will be seen at fluoroscopy. Mallory-Weiss tears are difficult to diagnose with esophagography. Like the esophageal perforations associated with Boerhaave syndrome, Mallory-Weiss tears usually involve the distal esophagus.

Boerhaave syndrome is named after physician Hermann Boerhaave (1668 to 1783) based on his detailed description of the condition in a 1724 manuscript.

Questions for Further Thought

1. What contrast agent(s) should be used to evaluate for a possible esophageal rupture?

View Answer

1. Water-soluble contrast material should be used initially, after confirming that the patient is not allergic to iodine. Rationale for beginning with water-soluble contrast material is that if barium leaks into the mediastinum it will not be resorbed and may result in mediastinitis. By comparison, water-soluble contrast material will be resorbed if it leaks into the mediastinum. The goal is to first exclude a large leak with water-soluble contrast material.

If the initial water-soluble contrast material images are negative for leak (as in this case, images not shown), the patient should drink thin barium. Rationale is that barium (as in this case) sometimes demonstrates leaks that are not seen with water-soluble contrast material. One theory for why barium is more effective than water-soluble contrast material for demonstrating leaks is that patients will take larger gulps of barium as it is less foul-tasting than water-soluble contrast material. These larger gulps of barium distend the esophagus more than small sips of water-soluble contrast material and may demonstrate a leak not visible with water-soluble contrast material. Additionally, barium is denser than water-soluble contrast material and is therefore better seen at fluoroscopy.

2. What contrast agent(s) should be used to evaluate for possible aspiration?

View Answer

2. If concern is for aspiration, the patient should consume small sips of thin barium. Rationale is that aspiration of water-soluble contrast material can result in a severe pneumonitis or pulmonary edema, whereas barium is more inert. If the patient is observed to aspirate barium, the patient should be instructed to cough up as much as possible.

Reporting Requirements

1. Immediately contact the clinical team regarding the chest radiograph to convey concern regarding possible air in the pleural space indicating an esophageal perforation. Chest CT is a reasonable recommendation following the chest radiograph to confirm that the retrocardiac air is in the pleural space rather than a hiatal hernia.

2. Immediately contact the clinical team following the esophagram to inform them of the esophageal rupture.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. This patient has a perforated esophagus.

2. Cardiothoracic surgery (or thoracic surgery) consultation is needed.

Answers

1. Water-soluble contrast material should be used initially, after confirming that the patient is not allergic to iodine. Rationale for beginning with water-soluble contrast material is that if barium leaks into the mediastinum it will not be resorbed and may result in mediastinitis. By comparison, water-soluble contrast material will be resorbed if it leaks into the mediastinum. The goal is to first exclude a large leak with water-soluble contrast material.

If the initial water-soluble contrast material images are negative for leak (as in this case, images not shown), the patient should drink thin barium. Rationale is that barium (as in this case) sometimes demonstrates leaks that are not seen with water-soluble contrast material. One theory for why barium is more effective than water-soluble contrast material for demonstrating leaks is that patients will take larger gulps of barium as it is less foul-tasting than water-soluble contrast material. These larger gulps of barium distend the esophagus more than small sips of water-soluble contrast material and may demonstrate a leak not visible with water-soluble contrast material. Additionally, barium is denser than water-soluble contrast material and is therefore better seen at fluoroscopy.

2. If concern is for aspiration, the patient should consume small sips of thin barium. Rationale is that aspiration of water-soluble contrast material can result in a severe pneumonitis or pulmonary edema, whereas barium is more inert. If the patient is observed to aspirate barium, the patient should be instructed to cough up as much as possible.

REFERENCES

1. Kanne JP, Rohrmann CA Jr, Lichtenstein JE. Eponyms in radiology of the digestive tract: historical perspectives and imaging appearances. Part 1. pharynx, esophagus, stomach and intestine. Radiographics 2006;26:129-142.

2. Teh E, Edwards J, Duffy J, Beggs D. Boerhaave’s syndrome: a review of management and outcome. Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg 2007;6:640-643.

CASE 1.12 CLINICAL HISTORY 32-year-old man with HIV and odynophagia.

FINDINGS Air-contrast barium swallow demonstrates three large, approximately 3-cm ulcers in the mid-esophagus.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS HIV ulcer, cytomegalovirus (CMV) ulcer, herpes simplex virus (HSV), pill-induced ulcer.

DIAGNOSIS CMV ulcer.

DISCUSSION Large ulcers are defined as ulcers greater than 1 cm. The differential diagnosis of large ulcers in an HIV-positive patient includes CMV and HIV infection. HSV may also present as ulcers at fluoroscopy, but HSV ulcers are typically less than 1 cm in size. Pill-induced ulcers are also typically small in size.

At fluoroscopy, CMV disease of the esophagus may manifest as large ulcers or a more diffuse esophagitis. In the HIV population, CMV infections usually occur in patients with advanced immunosuppression and CD4 counts <50. Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), CMV end-organ infection has become quite rare with 6 cases per 100 person-years reported in recent series. Of these acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients who experience end-organ CMV disease, approximately 5% to 10% will develop CMV esophagitis. Such patients typically present with fever, odynophagia, nausea, and chest pain.

As treatment of CMV esophagitis normally requires peripherally inserted central catheter line placement and a 21- to 28-day course of intravenous foscarnet or ganciclovir, endoscopy with tissue sampling is usually performed to distinguish between a CMV ulcer and an HIV ulcer.

Question for Further Thought

1. What would be the next step to confirm the diagnosis?

Reporting Requirement

1. Describe the size and location of ulcers.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. That a large ulcer in an HIV-positive patient may be caused by HIV disease or CMV.

Answer

1. Endoscopy and biopsy would be the steps to establish a diagnosis.

REFERENCES

1. Rubesin SE, Levine MS. Differential diagnosis of esophageal disease on esophagography. Appl Radiol 2001;10:11-21.

2. Balthazar EJ, Megibow AJ, Hulnick DH. Cytomegalovirus esophagitis and gastritis in AIDS. Am J Roentgenol 1985;144: 1201-1204.

3. Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KK, Brooks JT, Pau A, Masur H. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:1-198.

CASE 1.13 CLINICAL HISTORY 76-year-old woman with dysphagia.

FINDINGS Fluoroscopic images from a single-contrast barium swallow (A, B) demonstrate a smooth impression on the posterior aspect of the proximal cervical esophagus at approximately the C5-C6 level. The esophageal lumen is narrowed by less than 50%, and there is no ballooning of the upstream pharynx.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Esophageal web, prominent cricopharyngeal bar.

DIAGNOSIS Prominent cricopharyngeal bar.

DISCUSSION The cricopharyngeus muscle is a major component of the upper esophageal sphincter and is contracted in its basal state. Usually, the cricopharyngeus muscle relaxes when an individual swallows and is not visible at barium swallow. However, in individuals where the cricopharyngeus muscle fails to normally relax it is visible as an impression along the posterior wall of the proximal cervical esophagus, a condition sometimes referred to as cricopharyngeal achalasia.

The incidence of cricopharyngeal bars increases with age. Prominent cricopharyngeal bars are thought to, in general, be asymptomatic. Ballooning of the pharynx upstream from the bar may indicate that a bar is, in fact, symptomatic.

A prominent cricopharyngeal bar can be distinguished from an esophageal web as prominent bars are located posteriorly, whereas webs are usually located anteriorly.

Questions for Further Thought

1. Are most prominent cricopharyngeal bars asymptomatic or symptomatic?

2. What is the usual treatment of a prominent cricopharyngeal bar?

View Answer

2. Most bars are asymptomatic and therefore not treated. In rare cases, if the bar is thought to be the etiology of the patient’s symptoms, treatment options include injection of botulinum toxin into the cricopharyngeus muscle, dilatation of the bar, and myotomy.

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the presence of the bar.

2. Describe if there is any evidence that the bar is symptomatic (e.g., ballooning of the upstream pharynx or hold-up of compressed barium tablet at the level of bar with reproduction of patient symptoms).

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. Most cricopharyngeal bars are asymptomatic.

2. If the bar appears to be causing symptoms in the patient you are examining.

Answers

1. Asymptomatic.

2. Most bars are asymptomatic and therefore not treated. In rare cases, if the bar is thought to be the etiology of the patient’s symptoms, treatment options include injection of botulinum toxin into the cricopharyngeus muscle, dilatation of the bar, and myotomy.

REFERENCES

1. Leonard R, Kendall K, McKenzie SM. UES opening and cricopharyngeal bar in nondysphagic elderly and non elderly adults. Dysphagia 2004;19:182-191.

2. Dantas RO, Cook IJ, Dodds WJ, et al. Biomechanics of cricopharyngeal bars. Gastroenterology 1990;99:1269-1274.

3. Wang AY, Kadkade R, Kahrilas PJ, Hirano I. Effectiveness of esophageal dilation for symptomatic cricopharyngeal bar. Gastrointest Endosc 2005;61:148-152.

CASE 1.14 CLINICAL HISTORY 35-year-old woman with dysphagia.

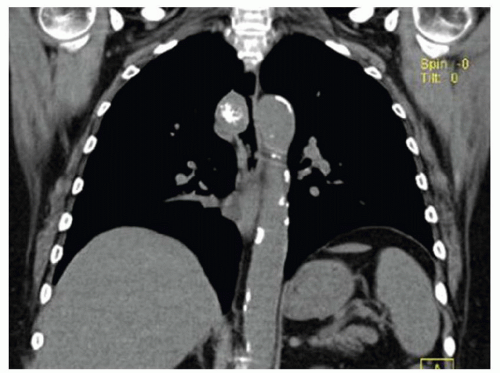

FINDINGS Lateral image from a barium swallow (A) demonstrates a smooth impression on the posterior aspect of the proximal esophagus. Frontal chest radiograph (B) demonstrates mass effect along the right side of the trachea. Contrast- enhanced CT image (C) demonstrates a diverticulum of Kommerell and an aberrant left subclavian artery arising from a right-sided aortic arch. This vessel passes posterior to the trachea and esophagus.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS BASED ON BARIUM SWALLOW Submucosal mass, extrinsic compression.

DIAGNOSIS Extrinsic compression on esophagus due to aberrant left subclavian artery, also right-sided aortic arch.

DISCUSSION The above area of mass effect seen at barium swallow has a “marble under the rug” appearance indicating that it is a submucosal mass or extrinsic process. The smoothness of the mucosa also excludes a mucosally based process.

The key to making this diagnosis is an awareness of the possibility of an aberrant subclavian artery running behind

the esophagus. Chest CT would be the next best step in this case to confirm and better delineate the patient’s vascular anatomy. Mistakenly recommending EGD with biopsy in this case could result in catastrophic bleeding.

the esophagus. Chest CT would be the next best step in this case to confirm and better delineate the patient’s vascular anatomy. Mistakenly recommending EGD with biopsy in this case could result in catastrophic bleeding.

The two most common vascular rings reported in adults are double aortic arch and right-sided aortic arch with aberrant left subclavian artery. Patients with these conditions may present with symptoms related to the respiratory track (e.g., dyspnea on exertion or stridor) or with dysphagia. Some patients may be asymptomatic.

Questions for Further Thought

1. What is dysphagia lusoria?

View Answer

1. The term dysphagia lusoria originates from the Latin word lusus naturae which means “freak of nature” and is most commonly defined as compression of the esophagus due to an aberrant right subclavian artery running behind the esophagus.

2. What would be treatment options for the above-described patient?

View Answer

2. If a vascular ring is asymptomatic, no treatment is warranted. The above patient reported symptoms of dysphagia and shortness of breath. At barium swallow, there was no impairment to the transit of liquid barium or the barium tablet. However, because of her reported symptoms and concern for eventual aneurysm rupture, the patient underwent surgical repair which included repairing the diverticulum of Kommerell with an aortic graft and then anastomosing the left subclavian artery to the aortic graft.

Reporting Requirements

1. Inform the ordering clinician of the abnormal study.

2. Recommend chest CT to evaluate for vascular ring.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. The extrinsic esophageal mass could be a vascular structure, and therefore EGD with biopsy should not be performed as the next step in diagnosis.

2. This patient may be asymptomatic or experience symptoms related to the respiratory or GI tracts.

Answers

1. The term dysphagia lusoria originates from the Latin word lusus naturae which means “freak of nature” and is most commonly defined as compression of the esophagus due to an aberrant right subclavian artery running behind the esophagus.

2. If a vascular ring is asymptomatic, no treatment is warranted. The above patient reported symptoms of dysphagia and shortness of breath. At barium swallow, there was no impairment to the transit of liquid barium or the barium tablet. However, because of her reported symptoms and concern for eventual aneurysm rupture, the patient underwent surgical repair which included repairing the diverticulum of Kommerell with an aortic graft and then anastomosing the left subclavian artery to the aortic graft.

REFERENCES

1. Kent PD, Poterucha TH. Aberrant right subclavian artery and dysphagia lusoria. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1637.

2. Grathwohl KW, Afifi AY, Dillard TA, Olson JP, Heric BR. Vascular rings of the thoracic aorta in adults. Am Surg 1999;65: 1077-1083.

CASE 1.15 CLINICAL HISTORY 68-year-old man with dysphagia.

FINDINGS Oblique (A) and frontal (B) fluoroscopic images from a barium swallow demonstrate an approximately 4-cm outpouching arising from the left aspect of the distal esophagus. This outpouching was seen to fill with contrast material and empty several times during the study.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Epiphrenic diverticulum, perforation.

DIAGNOSIS Epiphrenic diverticulum.

DISCUSSION An epiphrenic diverticulum is defined as an esophageal diverticulum that occurs within 10 cm of the diaphragm. Average size is 4 to 7 cm though diverticula as large as 14 cm have been reported. These pulsion diverticula result from herniation of the esophageal mucosa and submucosa through the musculature of the esophageal wall.

An epiphrenic diverticulum can be distinguished from a perforation as contrast material will be seen filling and emptying from a diverticulum, whereas contrast material will continue to accumulate at large sites of free perforation.

The etiology of epiphrenic diverticula is thought to be an underlying motility disorder such as achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, nutcracker esophagus, or a hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter. An esophageal motility disorder has been documented at barium swallow and/or manometry in 75% to 100% of patients with epiphrenic diverticula in recent series.

As an underlying motility disorder is thought to be the etiology of epiphrenic diverticula in most patients, the operating surgeon may perform a myotomy (to improve esophageal emptying) and a partial fundoplication procedure (to reduce the likelihood of reflux resulting from the myotomy) at the time of repair of the epiphrenic diverticulum.

Questions for Further Thought

1. What are common symptoms in patients with epiphrenic diverticula?

View Answer

1. Patients with epiphrenic diverticula may present with dysphagia, regurgitation of undigested food, chest pain, and/or weight loss.

2. What is the usual management of an epiphrenic diverticulum?

View Answer

2. Symptomatic epiphrenic diverticula are usually resected via a diverticulectomy with either an open or laparoscopic approach. Whether or not asymptomatic epiphrenic diverticula should be resected is a source of debate in the literature. Advocates of resection argue that a diverticulum can result in silent aspiration with significant morbidity and even mortality due to aspiration pneumonia. Advocates of “leaving alone” asymptomatic diverticula point to the potential for morbidity and even mortality due to surgery (which involves dissecting in the posterior mediastinum) in a patient who may never become symptomatic.

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the size of the diverticulum and distance of the diverticulum from the esophagogastric junction.

2. Look for more than one epiphrenic diverticulum as 15% of patients will have two epiphrenic diverticula.

3. Report whether the patient has esophageal dysmotility in addition to the epiphrenic diverticulum.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. That the patient has an epiphrenic diverticulum.

2. Whether the patient also has episodes of gastroesophageal reflux or a hiatal hernia, both of which could impact operative management.

Answers

1. Patients with epiphrenic diverticula may present with dysphagia, regurgitation of undigested food, chest pain, and/or weight loss.

2. Symptomatic epiphrenic diverticula are usually resected via a diverticulectomy with either an open or laparoscopic approach. Whether or not asymptomatic epiphrenic diverticula should be resected is a source of debate in the literature. Advocates of resection argue that a diverticulum can result in silent aspiration with significant morbidity and even mortality due to aspiration pneumonia. Advocates of “leaving alone” asymptomatic diverticula point to the potential for morbidity and even mortality due to surgery (which involves dissecting in the posterior mediastinum) in a patient who may never become symptomatic.

REFERENCE

1. Soares R, Herbella FA, Prachand VN, Ferguson MK, Patti MG. Epiphrenic diverticulum of the esophagus. From pathophysiology to treatment. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:2009-2015.

CASE 1.16 CLINICAL HISTORY 56-year-old man undergoing preoperative evaluation prior to lung transplant.

FINDINGS Fluoroscopic images from an air-contrast barium swallow (A, B) demonstrate numerous fine transverse folds circumferentially involving the esophageal wall. These folds appeared intermittently during the study. The patient was asymptomatic when these folds were visible.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Strictures from reflux esophagitis, feline esophagus.

DIAGNOSIS Feline esophagus.

DISCUSSION Feline esophagus refers to the pattern of fine transverse folds spaced 1 to 2 mm apart and involving the entire circumference of the esophagus. The transient nature of this finding and the fine, evenly spaced appearance of the mucosal folds distinguishes feline esophagus from strictures. A similar fold pattern occurs in the distal esophagus of cats.

When the esophagus shortens, the squamous mucosa undulates resulting in a “feline esophagus” appearance. Feline esophagus is a transient phenomenon and is thought to produce no symptoms. Feline esophagus may be seen as an isolated finding or in patients who also demonstrate GERD and hiatal hernias. Whether there is a true association between these conditions is unclear.

Question for Further Thought

1. What is the treatment for feline esophagus?

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe in the body of the report that intermittently during the study transverse folds were identified, in incidental finding.

2. Report whether gastroesophageal reflux events were observed.

3. Report if the patient has a hiatal hernia.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. Feline esophagus itself has no clinical significance, but this esophageal fold pattern has been reported to occur more frequently in patients with gastroesophageal reflux and/or a hiatal hernia.

Answer

1. No treatment is warrant for an isolated finding of feline esophagus.

REFERENCES

1. Williams SM, Harned RK, Kaplan P, Consigny PM. Work in progress: transverse striations of the esophagus: association with gastroesophageal reflux. Radiology 1983;146:25-27.

2. Samadi F, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Katzka DA, Laufer I. Feline esophagus and gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Roentgenol 2010;194:972-976.

3. Furth EE, Rubesin SE, Rose D. Radiologic-pathologic conferences of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania: Feline esophagus. Am J Roentgenol 1995;164:900.

CASE 1.17 CLINICAL HISTORY 67-year-old woman with dysphagia and experiencing episodes of regurgitation of a large sausage-like mass which she could not expel.

FINDINGS Air-contrast barium swallow study demonstrates multiple smooth, expansile, sausage-shaped masses (A, B). Contrast material coats all sides of the masses, and the masses were mobile during real-time imaging.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Fibrovascular polyps, leiomyomas.

DIAGNOSIS Fibrovascular polyps.

DISCUSSION Fibrovascular polyps are rare benign tumors. These tumors usually arise near the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle and gradually elongate over a period of years as they are dragged inferiorly due to esophageal peristalsis.

Patients sometimes present with weight loss and retrosternal pain. Polyp ulceration can result in bleeding. The patient may experience regurgitation of a lobulated mass with a broad stalk. In some cases, airway obstruction and asphyxia have been reported.

At fluoroscopy, fibrovascular polyps appear as intraluminal filling defects. An intraluminal location is suggested by the presence of contrast material coating all sides of the mass in multiple projections. Also, as fibrovascular polyps are usually tethered by a stalk, they often appear mobile at barium swallow. By comparison, leiomyomas typically do not appear polypoid but more often have a “marble under the rug” appearance.

Question for Further Thought

1. What are treatment options for fibrovascular polyps?

View Answer

1. Depending on the size of the polyp, it may be amenable to endoscopic excision. Alternatively, a thoracotomy may be required to remove larger polyps.

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the size and location of the lesions.

2. Attempt to characterize the lesions as intraluminal in location which favors a diagnosis of fibrovascular polyps.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. This patient has intraluminal esophageal masses that are most likely fibrovascular polyps.

2. Surgical resection likely will be necessary to alleviate patient symptoms.

Answer

1. Depending on the size of the polyp, it may be amenable to endoscopic excision. Alternatively, a thoracotomy may be required to remove larger polyps.

REFERENCES

1. Levine MS, Rubesin SE. Diseases of the esophagus: diagnosis with esophagography. Radiology 2005;237:414-427.

2. Morin FD, Bret PM, Gret P, Palayew MJ. General case of the day: Fibrovascular polyp of the esophagus. Radiographics 1992;12:845-847.

3. Jang GC, Clouse ME, Fleischner FG. Fibrovascular polyps: a benign intraluminal tumor of the esophagus. Radiology 1969;92: 1196-1200.

CASE 1.18 CLINICAL HISTORY 43-year-old woman with dysphagia.

FINDINGS Single-contrast image (A) demonstrates a 2-cm contour abnormality in the middle third of the esophagus. The contour abnormality has the appearance of a “marble under a rug” with respect to the esophageal lumen. The esophageal mucosa is smooth, best seen in the air-contrast image (B).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Submucosal mass (-omas: lipoma, leiomyoma, neuroma, fibroma, neurofibroma), extrinsic compression (lymph node, vascular structure, duplication cyst).

DIAGNOSIS Submucosal mass (granular cell tumor).

DISCUSSION The smooth mucosa and “marble under a rug” appearance make a mucosal abnormality extremely unlikely. A submucosal mass rather than an area of extrinsic compression can be favored by noting the normal outer contour of the esophagus at this level. By comparison, areas of extrinsic compression often distort the outer esophageal contour.

As a radiologist, you have done your job by identifying the abnormality as a submucosal mass for which CT (to evaluate for a fat containing lipoma) or EUS with possible tissue sampling could be performed as the next step to establish the diagnosis.

Granular cell tumors of the esophagus are rare tumors and are thought to be of neurogenic origin. Diagnosis is made based on endoscopic biopsy. Granular cell tumors have been reported in a variety of locations, including the skin, larynx, breast, and vulva. The “granularity” of these tumors is caused by accumulation of lysosomes in the cytoplasm.

When located in the esophagus, granular thecomas most frequently occur in the distal esophagus and are usually small at the time of detection with 75% <1 cm in size in one series. In many patients with small granular cell tumors, these tumors are thought to be an incidental finding at the time of endoscopy rather than the actual cause of the patient’s dysphagia. Granular cell tumors are not thought to produce dysphagia until they reach at least 1 cm in size.

A literature search for granular cell tumors of the esophagus reveals a smattering of case reports and case series. Given the relative rarity of this tumor, the best treatment

strategy is yet to be defined. In general, once the diagnosis of a granular cell tumor is made with endoscopic biopsy, periodic surveillance with endoscopy or fluoroscopy is thought to be adequate to assess for size stability. The optimal surveillance frequency is yet to be defined. If tumor removal is desired, endoscopic and surgical removal are options.

strategy is yet to be defined. In general, once the diagnosis of a granular cell tumor is made with endoscopic biopsy, periodic surveillance with endoscopy or fluoroscopy is thought to be adequate to assess for size stability. The optimal surveillance frequency is yet to be defined. If tumor removal is desired, endoscopic and surgical removal are options.

Question for Further Thought

1. What is the management of esophageal granular cell tumors?

View Answer

1. Esophageal granular cell tumors are such rare tumors that appropriate management is somewhat controversial. These benign tumors are thought to have no malignant potential. Therefore, a conservative approach with periodic (often yearly) surveillance to confirm size stability is suggested in patients with small (<1 cm), asymptomatic tumors.

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the location of the abnormality.

2. Recommend EUS with possible tissue sampling or cross-sectional imaging (to evaluate for lipoma) for further evaluation.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. The patient has a submucosal esophageal mass.

2. Whether the mass is obstructing based on transit of liquid barium and the 12.5-mm compressed barium tablet past the level of the mass.

Answer

1. Esophageal granular cell tumors are such rare tumors that appropriate management is somewhat controversial. These benign tumors are thought to have no malignant potential. Therefore, a conservative approach with periodic (often yearly) surveillance to confirm size stability is suggested in patients with small (<1 cm), asymptomatic tumors.

REFERENCES

1. Goldblum JR, Rice TW, Zuccaro G, Richter JE. Granular cell tumors of the esophagus: a clinical and pathologic study of 13 cases. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;62:860-865.

2. Voskull JH, van Dijk MM, Wagenaar SS, van Vilet AC, Timmer R, van Hees PA. Occurrence of esophageal granular cell tumors in The Netherlands between 1998 and 1994. Dig Dis Sci 2001;46: 1610-1614.

CASE 1.19 CLINICAL HISTORY 42-year-old woman with newly diagnosed HIV infection and CD4 count of 0 presents with epigastric pain.

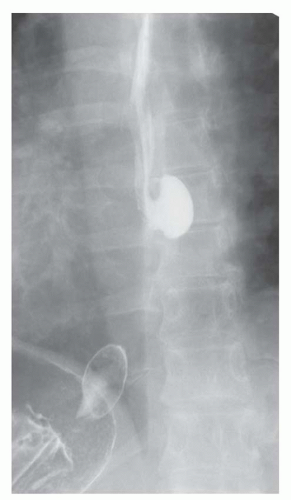

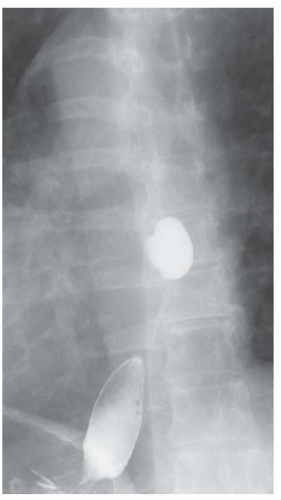

FINDINGS Single-contrast swallow study demonstrates a large, approximately 3-cm outpouching of contrast material along the distal third of the esophagus (A, B).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Candidiasis, CMV ulcer, HSV ulcer, HIV ulcer.

DIAGNOSIS HIV ulcer (idiopathic esophageal ulceration).

DISCUSSION In the current era of HAART for HIV disease, compliant HIV-positive patients presenting with odynophagia are more likely to have symptoms caused by GERD rather than an opportunistic infection.

Of those patients who have an opportunistic infection as the etiology of odynophagia, Candida is the most common etiology followed by CMV, HSV type 1 or 2, and mycobacterial tuberculosis infection. Idiopathic ulcers or “HIV ulcers” are defined as ulcers that are negative on biopsy for known viral and fungal agents with HIV-like viral particles visible at electron microscopy.

Esophageal candidiasis appears as extensive confluent areas of mucosal irregularity. CMV appears as a large ulcer(s) or small ulcer(s) in the mid- to distal esophagus and is indistinguishable from an HIV ulcer at esophagography. HSV appears as multiple small (<1 cm) ulcers at esophagography.

Large ulcers are defined as ulcers greater than 1 cm. Endoscopy and biopsy with brushings and culture are needed to distinguish a CMV ulcer from an HIV ulcer. If biopsies and cultures are negative, the ulcer is termed “idiopathic esophageal ulceration” in the gastroenterology literature and an “HIV ulcer” in the radiology literature.

Determining whether an ulcer is caused by HIV itself or an opportunistic infection is critical because HIV ulcers are treated with HAART and sometimes steroids whereas opportunistic infections are treated with tailored medicines such as ganciclovir for CMV ulcers and fluconazole for candidiasis.

Question for Further Thought

Reporting Requirements

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. A large ulcer in an HIV-positive patient may be caused by HIV disease or CMV.

2. Endoscopy with biopsy and culture is needed to distinguish between an HIV ulcer and a CMV ulcer.

Answer

1. Endoscopy and biopsy.

REFERENCES

1. Levine MS, Loercher G, et al. Giant, human immunodeficiency virus-related ulcers in the esophagus. Radiology 1991;180:323-326.

2. Werneck-Silva AL, Prado IB. Role of upper endoscopy in diagnosing opportunistic infections in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:1050-1056.

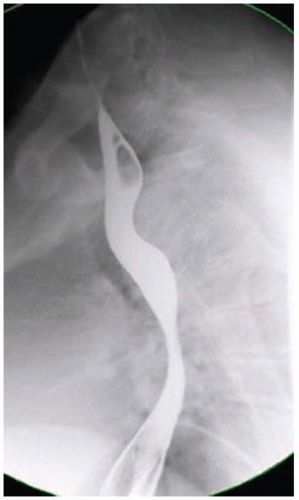

CASE 1.20 CLINICAL HISTORY 56-year-old man with dysphagia.

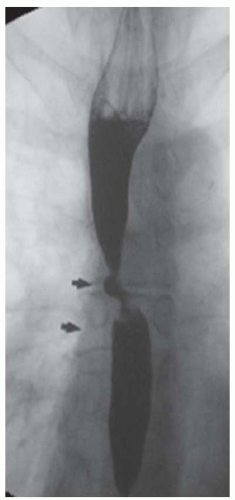

FINDINGS Fluoroscopic images (A, B) from an air-contrast barium swallow demonstrate a circumferential narrowing of the distal esophagus. Also note small sliding-type hiatal hernia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Ring, stricture.

DIAGNOSIS Lower esophageal ring (Schatzki ring).

DISCUSSION The ring visible in both of the above images is referred to as a Schatzki ring. The above ring is occurring at the level of the B ring. The B ring marks the esophagogastric junction, is a mucosal ring, and is covered by squamous epithelium along the upper surface and columnar epithelium along the undersurface.

In image A above, a second ring is visible a few millimeters above the Schatzki ring. This more cranial ring is termed an “A ring.” The A ring is a muscular contraction at the junction of the tubular and vestibular esophagus and is covered with squamous epithelium on both sides.

The etiology of lower esophageal rings is uncertain. Chronic ingestion of medications that damage esophageal mucosa and chronic GERD have been posited as causative factors.

Rings may be asymptomatic or symptomatic depending on the remaining luminal diameter of the esophagus. When performing a barium swallow, it is important to administer a compressed barium tablet, evaluate whether the tablet becomes lodged at the level of the ring, and report whether the patient experienced symptoms when the tablet was lodged. If symptomatic, rings may be treated with mechanical or balloon dilatation along with medical management of GERD if present.

Schatzki rings are named after radiologist Richard Schatzki who described ring-associated dysphagia in 1953.

Questions for Further Thought

1. What esophageal luminal diameter is thought to be associated with symptoms of dysphagia?

View Answer

1. Mucosal rings less than 13 mm in diameter are usually symptomatic. Rings more than 20 mm in diameter are usually asymptomatic, and between 13 and 20 mm is a gray area.

2. What is the steakhouse syndrome?

View Answer

2. Steakhouse syndrome refers to esophageal obstruction due to an ingested foreign body that becomes stuck at the level of an esophageal ring. Patients may present with dysphagia and chest pain.

Reporting Requirements

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. Most lower esophageal rings are asymptomatic.

2. Rings that impede transit of the 12.5-mm compressed barium tablet are more likely to be symptomatic.

Answers

1. Mucosal rings less than 13 mm in diameter are usually symptomatic. Rings more than 20 mm in diameter are usually asymptomatic, and between 13 and 20 mm is a gray area.

2. Steakhouse syndrome refers to esophageal obstruction due to an ingested foreign body that becomes stuck at the level of an esophageal ring. Patients may present with dysphagia and chest pain.

REFERENCES

1. Jalil S, Castell DO. Schatzki’s ring: a benign cause of dysphagia in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol 2002;35:295-298.

2. Schatzki R, Gary JE. Dysphagia due to a diaphragm-like localized narrowing in the lower esophagus (lower esophageal ring). Am J Roentgenol 1953;70:911-922.

CASE 1.21 CLINICAL HISTORY 66-year-old woman with dysphagia.

FINDINGS Frontal film from a single-contrast barium swallow demonstrates an approximately 5-cm area of narrowing (A) in the mid-esophagus. The mucosa itself appears primarily smooth in the area of narrowing (A). Noncontrast CT scan (B) demonstrates a soft-tissue mass completely encasing the esophagus (B) and also surrounding the left lower lobe bronchus.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Bronchogenic carcinoma, esophageal cancer, lymphoma.

DIAGNOSIS Bronchogenic carcinoma.

DISCUSSION When a mass-like area is identified at barium swallow, the mucosal surface should be evaluated. Smooth mucosa suggests a submucosal or an extrinsic process as in this case. By comparison, mucosal irregularity suggests a mucosa-based process.

If a process is characterized as submucosal or extrinsic, cross-sectional imaging or EUS with tissue sampling may be the next step to try to determine the etiology. By comparison, endoscopy with tissue sampling is usually the next step for mucosal processes. Malignant extrinsic pathologies that can narrow the esophagus include bronchogenic carcinoma and lymphoma.

Questions for Further Thought

1. How would a tissue diagnosis be obtained in this patient?

View Answer

1. Options for tissue diagnosis in this patient would include bronchoscopy or EGD/EUS with biopsy.

2. What stage is lung cancer that directly invades the esophagus?

3. What treatment options are available for this patient?

View Answer

3. Treatment options would include placement of a percutaneous gastrostomy tube for feeding purposes (as was done for this patient).

Reporting Requirements

1. Describe the location of the abnormality.

2. Indicate high level of concern for malignancy.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. This patient has a large, likely extrinsic mass that is highly suspicious for malignancy.

2. Chest CT may be helpful to further characterize the mass.

3. Whether the mass is obstructing based on transit of liquid barium and the 12.5-mm compressed barium tablet past the level of the mass.

Answers

1. Options for tissue diagnosis in this patient would include bronchoscopy or EGD/EUS with biopsy.

2. Lung cancer that directly invades the esophagus is designated as T4 disease.

3. Treatment options would include placement of a percutaneous gastrostomy tube for feeding purposes (as was done for this patient).

REFERENCE

1. DiPerna CA, Wood DE. Surgical management of T3 and T4 lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005;11:5038s-5044s.

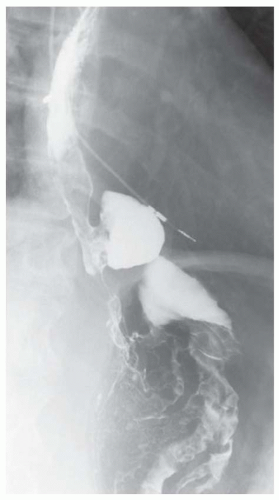

CASE 1.22 CLINICAL HISTORY 57-year-old woman with history of multiple esophageal surgeries and leakage from right chest.

FINDINGS Lateral chest radiograph from an esophagram and fistulagram. Prior to this image being obtained, the patient ingested water-soluble contrast material by mouth. The patient’s right chest wall skin defect was also cannulated, and sterile water-soluble contrast material was injected.

DIAGNOSIS Colonic interposition; also fistula from right chest wall to blind-ending esophageal remnant.

DISCUSSION After esophagectomy, options for a replacement conduit include stomach, jejunum, and colon. The location of the conduit may be orthotopic, retrosternal, left or right chest, or subcutaneous. The anastomosis may be thoracic or cervical.

This patient had a remote history of a colonic interposition in the 1970s for a benign esophageal stricture. The patient developed a stricture at the esophagocolonic anastomosis, and the colonic interposition was revised with a new colonic interposition. The patient then developed a fistulous communication between her skin and the remaining blind-ending esophageal remnant.

Historically, colon was the most frequently used conduit. Presently, stomach is the most frequently used conduit. Current indications for selecting a colonic rather than a gastric conduit include history of prior gastrectomy and gastric involvement by tumor. If a colonic interposition is performed, the right colon is used more frequently than the left colon.

Short-term complications following colonic interposition include anastomotic leak. Long-term complications include stricture. Strictures more frequently form at the esophagocolonic anastomosis rather than the colonic-small bowel anastomosis.

Questions for Further Thought

1. What contrast agent should be used if there is concern for an esophageal leak into the mediastinum?

View Answer

1. Water soluble. Rationale: water-soluble contrast material will be resorbed if it leaks into the mediastinum. On the other hand, barium is inert, is not resorbed, and can trigger an inflammatory response. Keep in mind that barium should be used if there is concern for aspiration as water-soluble contrast material can result in a severe pneumonitis and pulmonary edema if aspirated. Also remember that water-soluble contrast material contains iodine, so confirm that the patient does not have an iodine allergy before administering water-soluble contrast material. If the patient is allergic to iodine, depending on the severity of the reaction the swallow study can be performed following a steroid prep.

2. What contrast agent should be used to evaluate a fistula?

View Answer

2. The safest contrast agent to use is a sterile, water-soluble contrast agent. Iodinated contrast material used for intravascular opacification at CT satisfies both of these criteria. As above, confirm that the patient is not allergic to iodine before administering iodinated contrast material.

Reporting Requirement

1. Notify the ordering physician of the presence of a fistula.

What the Treating Physician Needs to Know

1. The patient’s colonic conduit is intact without leak or stricture.

2. There is a fistulous communication between the patient’s right chest and the esophageal remnant.

Answers

1. Water soluble. Rationale: water-soluble contrast material will be resorbed if it leaks into the mediastinum. On the other hand, barium is inert, is not resorbed, and can trigger an inflammatory response. Keep in mind that barium should be used if there is concern for aspiration as water-soluble contrast material can result in a severe pneumonitis and pulmonary edema if aspirated. Also remember that water-soluble contrast material contains iodine, so confirm that the patient does not have an iodine allergy before administering water-soluble contrast material. If the patient is allergic to iodine, depending on the severity of the reaction the swallow study can be performed following a steroid prep.

2. The safest contrast agent to use is a sterile, water-soluble contrast agent. Iodinated contrast material used for intravascular opacification at CT satisfies both of these criteria. As above, confirm that the patient is not allergic to iodine before administering iodinated contrast material.

REFERENCE

1. Davis PA, Law S, Wong J. Colonic interposition after esophagectomy for cancer. Arch of Surg 2003;138:303-308.

CASE 1.23 CLINICAL HISTORY 72-year-old man with dysphagia.

FINDINGS Fluoroscopic images from an air-contrast barium swallow (A, B, C) demonstrate an approximately 3-cm outpouching with smooth margins arising from the middle third of the esophagus. Contrast material remains in the outpouching after the neighboring esophageal lumen at the same level has cleared.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Pulsion diverticulum, traction diverticulum.

DIAGNOSIS Features of both, most likely a pulsion diverticulum.

DISCUSSION Diverticula are divided into pulsion and traction diverticula. Pulsion diverticula are thought to result from a dysmotility disorder. For example, failure of normal relaxation of the cricopharyngeus muscle is thought to contribute to the formation of both Zenker and Killian-Jamieson diverticula. Failure of normal relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter is thought to contribute to the formation of epiphrenic diverticulum. Pulsion diverticula most commonly involve the proximal or distal esophagus.

By comparison, traction diverticula are due to an adjacent inflammatory or infectious process that distorts esophageal anatomy. Traction diverticula most commonly occur in the mid-esophagus and are thought to be associated with, for example, inflammation of adjacent mediastinal lymph nodes. Traction diverticula also may occur in the cervical esophagus secondary to inflammation from cervical spine hardware.