This article summarizes the current literature on office-based management of low-grade, noninvasive bladder cancer. Discussion includes differences in recurrence and progression rates between neoplasm grades and stages, role of visual grading for diagnosis, cost advantages of treatment outside the operating room, and a step-by-step description of office-based procedures.

Key points

- •

Low-grade (LG) noninvasive bladder cancer is a heterogeneous disease with variable recurrence and progression rates, and helpful tools are available to appropriately risk-stratify patients.

- •

Substantial cost is accrued from management of recurrent LG bladder cancer in operating rooms.

- •

Office-based management of LG noninvasive bladder cancer is a cost-effective, well-tolerated, and safe strategy when applied to suitable patients.

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the fourth most common malignancy among men in the United States, with 52,050 expected newly diagnosed cases in 2011 and 17,320 cases among women. Although 14,990 deaths were expected during the same time period, most cases of bladder cancers are noninvasive and LG. Despite the low risk for lethality, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) has a substantial risk for recurrence and progression occurs in some cases.

Recurrent disease has long been managed with resection and fulguration. This is often performed in an operating room, resulting in significant expense, possible morbidity, and repeated exposure to general anesthesia. Some investigators have proposed alternative strategies for managing LG NMIBC, including office-based interventions in attempts to control cost and improve quality of life without exposing patients to unnecessary risks. This article examines the rationale, efficacy, and logistics of managing NMIBC in the office setting, thereby avoiding the need for intraoperative management for all recurrent LG NMIBC.

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the fourth most common malignancy among men in the United States, with 52,050 expected newly diagnosed cases in 2011 and 17,320 cases among women. Although 14,990 deaths were expected during the same time period, most cases of bladder cancers are noninvasive and LG. Despite the low risk for lethality, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) has a substantial risk for recurrence and progression occurs in some cases.

Recurrent disease has long been managed with resection and fulguration. This is often performed in an operating room, resulting in significant expense, possible morbidity, and repeated exposure to general anesthesia. Some investigators have proposed alternative strategies for managing LG NMIBC, including office-based interventions in attempts to control cost and improve quality of life without exposing patients to unnecessary risks. This article examines the rationale, efficacy, and logistics of managing NMIBC in the office setting, thereby avoiding the need for intraoperative management for all recurrent LG NMIBC.

Low-grade non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

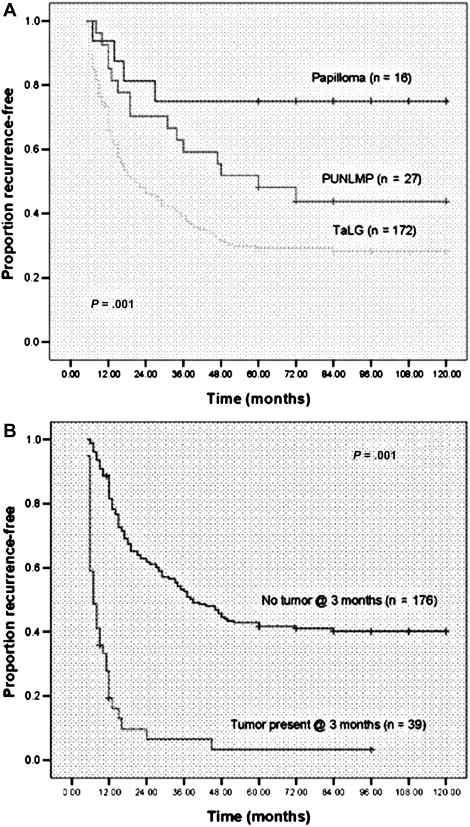

In efforts to clarify confusion surrounding papillary bladder tumors, the World Health Organization and the International Society of Urological Pathology created a more stringent pathology classification scheme for bladder cancer. This system classifies non-muscle invasive papillary tumors into papilloma, papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential, LG, and high grade. There are significant differences in recurrence rates between tumors in this schema ( Fig. 1 ). The risk for the first 3 of these groups for progression to invasive disease is low, with 0% to 1.2% for papillomas, 0% to 8% for papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential, and 5% to 13% for LG papillary tumors in contrast to progression rates greater than 45% for high-grade tumors. Although investigators report a variety of predictors for recurrence and progression, the strongest seem to include tumor stage, size, number, early previous recurrences, and presence of carcinoma in situ (CIS).

The updated classification scheme provides additional information to better risk-stratify patients, distinguishing those who may need more-aggressive therapy from those who do not. Yet many perform cystoscopy every 3 months for the first 2 or 3 years, every 6 months for the following 2 years, and yearly thereafter, regardless of the risk of recurrence and progression. However, this strategy has not been shown more effective than less-rigorous surveillance protocols and subjects patients to frequent interventions that may not be of benefit and increase the cost of care. As a result, most argue for an approach tailored to patients’ risk of recurrence and progression.

Not all investigators agree with this approach. Leblanc and colleagues presented data for patients initially diagnosed with Ta grade 1 disease and with follow-up of more than 5 years. They reported an overall recurrence rate of 55%, with 14% having recurrences more than 5 years from initial diagnosis. Progression to higher grade or stage was identified in 37%, but only 3.3% developed muscle invasive disease. These investigators argue for frequent cystoscopic evaluation continuing beyond 5 years.

Visual grading

An additional key to appropriately offer less-invasive treatment without harming those who require more-aggressive care is the ability to reliably differentiate between low-risk and high-risk tumors based on visual appearance. Herr and colleagues found that experienced urologists were able to correctly identify 93% of lesions that had recurred after initial diagnosis of NMIBC as Ta grade 1 tumors. When voided urine cytology was added, accuracy increased to 99% for Ta grade 1 tumors. The investigators did not outline specific cystoscopic criteria that the performing urologist used but rather this determination was made by an overall impression of the surgeon based on experience. Other investigators have attempted to more rigorously outline criteria for higher-risk tumors. Satoh and colleagues found that tumors greater than 1 cm, those sessile in nature, and nonpapillary tumors were more likely to have muscle invasion.

Cost

Management of bladder cancer has the highest cost of any malignancy per patient covered by Medicare, with lifetime costs per patient ranging from $96,000 to $187,000. When modeling for patients of all ages, including those younger than 65 years, another group estimated the lifetime costs for patients presenting with bladder cancer between $99,270 and $120,684. They found that 60% of these cost were related to surveillance and treatment of recurrences, with patients averaging 2.9 cystoscopies per patient per year.

Study of cost-effective treatment of bladder cancer is limited and has not been incorporated into treatment guidelines. However, it is intuitive that substantial cost reductions may be achieved by shifting surveillance from frequent invasive procedures to less-frequent, risk-stratified protocols that use office-based management strategies in appropriately selected patients. Strategies that risk-stratify patients for surveillance cystoscopy and upper-tract imaging can reduce the frequency with which patients who have low-risk disease undergo costly and invasive procedures without exposing them to additional risk.

Treatment and surveillance schedules for early-stage bladder cancer vary greatly by provider and higher intensity does not seem to prevent later treatments or need for major medical interventions, such as cystectomy. Furthermore, those who used high-intensity treatment and surveillance were more likely to use major medical interventions later on, contributing to higher costs.

Office-based fulguration instead of resection in operating rooms has the benefit of avoiding outpatient facility, anesthesia, and pathologist fees in addition to decreasing patient time commitment and convalescence. Recognizing the potential cost savings of in-office procedures for the management of NMIBC, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services increased physician reimbursement for office-based endoscopic procedures by a factor of almost 10 for office fulguration and by 3 for biopsy. However, in one faculty practice, this change in reimbursement did not decrease the overall cost for treating patients but instead resulted in an almost doubling in charges.

Office-based management

Several investigators have reported various approaches to office-based management of LG NMIBC with good outcomes. Outpatient fulguration with electrocautery of LG bladder tumors was described more than 30 years ago with substantial cost savings over inpatient management. Herr then described management of 185 patients with superficial bladder tumors using a flexible cystoscope, fulguration with a Bugbee electrode, and only local anesthethsia. No patient requested that the procedure be stopped and at 24 months, 63% remained tumor-free. Wedderburn and coworkers reported on office-based treatment of 103 consecutive patients with recurrent LG Ta lesions using only nonanesthetizing lubricant gel, with 80% reporting negligible or mild discomfort and only 2 patients reporting that they would have preferred the procedure to be done under a general anesthetic. No recurrence was found in 50.5%, with a median follow-up of 21 months, but 25.5% of those that recurred did so at the original treatment site. An update of the experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center reported outcomes of office-based fulguration alone in 123 patients with recurrent NMIBC. Median follow-up was 6.84 years, and 73% had no evidence of disease, 21.7% were alive with disease, and 2.2% died from disease.

Variations on the use of traditional fulguration with electrocautery have been reported. Muraishi and colleagues described using a biopsy forceps with electrocautery to simultaneously cauterize and obtain a specimen for pathologic evaluation. They subsequently updated this procedure by insufflating the bladder with CO 2 , injecting the tumor with a mixture of 2% xylocaine and indigo carmine, and then resecting the tumor with hot biopsy cup forceps.

Use of the holmium:YAG laser alone or in combination with intravesical agents has also been reported for management of NMIBC. Jonler and colleagues described ablation with a holmium laser in an office setting, using urethral lidocaine alone in 52 patients. No pain was reported in 86% and all stated they preferred this method to traditional transurethral resection (TUR). Unfortunately, no follow-up data were provided to assess the adequacy of treatment. Other investigators have reported limited follow-up but with acceptable recurrence rates.

In a nonrandomized study comparing holmium laser with traditional TUR, Zhu and colleagues reported using the laser to resect rather than just ablate NMIBC under epidural anesthesia. They reported no difference in recurrence rate between the 2 therapies with mean follow-up of 34 months but with the advantage of fewer bladder perforations and bleeding complications. However, resection rather than ablation with laser may be too difficult or uncomfortable to do in the office and access to the laser generator in this setting may limit its use. For these and other logistical reasons, the authors favor office-based ablation with electrocautery rather than office-based holmium laser ablation.

Patient selection

Proper risk stratification is critical for appropriate application of office-based management of NMIBC to those patients who are likely to benefit without exposing other patients to undue risk for recurrence or progression. Millan-Rodriguez and colleagues risk-stratified patients with NMIBC into low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk groups with good discriminative ability for recurrence, progression, and mortality using data from 1529 patients. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) combined data from 7 randomized trials comparing treatments after initial diagnosis of Ta, T1, and CIS bladder cancer in more than 2500 patients to create tables that allow for calculation of short-term and long-term risks of recurrence and progression. Number of tumors, tumor size, prior recurrence rate, stage, presence of CIS, and grade are used to place each patient into a 4-tier risk group both for recurrence and progression at 1 year and 5 years ( Tables 1 and 2 ). A calculator based on these data is available at: http://www.eortc.be/tools/bladdercalculator/ .