| 6 | Normal Appearance of the Intestinal Segments |

Normal Rectum

The rectum is the most distal colon segment, extending from the anal canal to the rectosigmoid junction. The dentate line marks the boundary between the anal canal and the rectum, and is characterized by a mixture of rectal mucosa (columnar epithelium) and sensitive anal skin (squamous epithelium). The fingerlike proximal ends of the squamous epithelium are somewhat thickened, forming the anal papilla. At the pouch-like distal ends of the columnar epithelium, also fingerlike in form, are the anal crypts, at the base of which are the anal glands. There is no distinct anatomical demarcation between the rectum and the sigmoid colon. As a rule, the boundary between the rectum and the sigmoid colon is considered to be at a height of 16 cm proximal to the anocutaneous line (measured using a stiff rectoscope), at which point the colon usually angles sharply toward the sigmoid colon. This demarcation is significant for treating tumors: distal to this line, rectal carcinomas in certain stages are treated differently than colon carcinomas located proximal to the line.

The rectum is the most distal colon segment, extending from the anal canal to the rectosigmoid junction. The dentate line marks the boundary between the anal canal and the rectum, and is characterized by a mixture of rectal mucosa (columnar epithelium) and sensitive anal skin (squamous epithelium). The fingerlike proximal ends of the squamous epithelium are somewhat thickened, forming the anal papilla. At the pouch-like distal ends of the columnar epithelium, also fingerlike in form, are the anal crypts, at the base of which are the anal glands. There is no distinct anatomical demarcation between the rectum and the sigmoid colon. As a rule, the boundary between the rectum and the sigmoid colon is considered to be at a height of 16 cm proximal to the anocutaneous line (measured using a stiff rectoscope), at which point the colon usually angles sharply toward the sigmoid colon. This demarcation is significant for treating tumors: distal to this line, rectal carcinomas in certain stages are treated differently than colon carcinomas located proximal to the line.

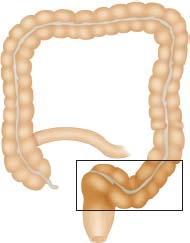

The rectal segment between these two demarcations runs fairly straight (hence “rectum”) and typically has three large folds protruding into the lumen from the sides, the so-called Kohlrausch folds (Fig. 6.1). The distal segment of the rectum is wider than the proximal segment, forming the rectal ampulla. The proximal rectum is located intraperitoneally, while the distal segment becomes retroperitoneal in the abdominal cavity. The peritoneal reflection, about 7-8 cm from the anal margin, is deeper on the ventral side near the pouch of Douglas than on the dorsal side. This is important for transmural injuries of the rectum.

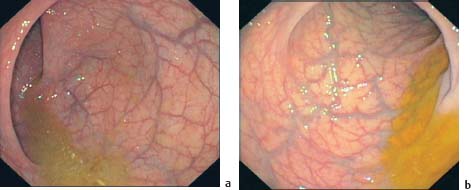

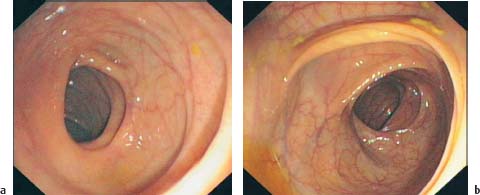

6.1 Normal vascular patterns in the distal rectum

6.1 Normal vascular patterns in the distal rectum

a Fine, but clearly visible vascular pattern contrasting sharply with smooth, reflective mucosa.

b More pronounced venous blood vessels, somewhat prominent.

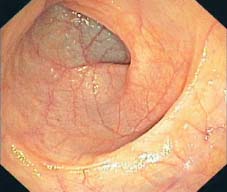

c Spidery, prominent venous blood vessel with clearly visible vessel branches supplying it.

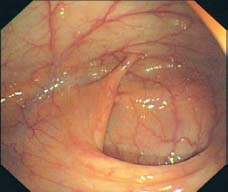

d Very prominent venous blood vessels, borderline pathology, in a patient with inner hemorrhoids.

Fig. 6.1 Rectum with crescent-shaped, infolding rectal valves. Despite the straight path of the rectum, the folds obscure visualization. Note the distinct and pronounced vascular pattern with the typically clearly visible submucosal veins.

Fig. 6.2 Anorectal area and upper anal canal, with forward-viewing instrument. Contractions of the sphincter obscure visualization with a forward-viewing instrument, especially of the surrounding dentate line, which is barely visible.

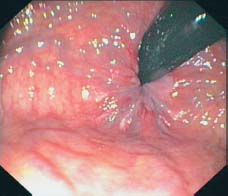

Fig. 6.3 Anorectal area and upper anal canal viewed with a retroflexed endoscope. Retro-flexing the endoscope allows a better view of the dentate line; the transition between the pale squamous epithelium of the anal canal and the reddish columnar epithelium of the rectum is visible. The anal crypts and the slightly thickened anal papilla are also clearly visible (e.g., at about the 9-o’clock position).

Fig. 6.4 Close-up view of the dentate line in inversion. The intertwining, fingerlike squamous epithelium and columnar epithelium are clearly visible. Two anal crypts can be seen at about the 2-o’clock and 3-o’clock positions and at about the 12-o’clock position (partially obscured by the instrument) a hypertrophied anal papilla.

Fig. 6.5 Normal hemorrhoidal plexus viewed in retroflexion. The hemorrhoidal cushions, which help seal the anus, appear as bluish swellings. Vascular branches can be seen coming from the distal rectum.

Normal Sigmoid Colon

The sigmoid colon is located in the lower left abdomen between the rectum and the descending colon. Its name is derived from its S shape (sigma = the Greek letter S).

The sigmoid colon is located in the lower left abdomen between the rectum and the descending colon. Its name is derived from its S shape (sigma = the Greek letter S).

The sigmoid colon is completely intraperitoneal, attached and supplied by its own mesentery (mesosigmoid) to the posterior abdominal wall. Due to its intraperitoneal position, the sigmoid colon is usually highly mobile. However, previous lower abdominal surgery, especially gynecological operations and inflammation (e.g., diverticular disease), can cause adhesions, fixing it to the abdominal wall, making passage difficult, and in rare cases even impossible. The length of the sigmoid colon can vary greatly; usually 15-30 cm long, it can be significantly longer (a so-called elongated sigmoid, not considered a pathology), which can lead to looping, and create significant problems for advancing the endoscope. As already mentioned, there is no clear anatomical demarcation at the distal end between the sigmoid colon and the rectum, though the rectosigmoid junction is usually rather sharply angled. The sigmoid-descending junction is often acutely angled, particularly in slender patients, making passage difficult. This is because the back wall of the descending colon is fixed retroperitoneally to the posterior abdominal wall, while the sigmoid colon distal to it is mobile. Advancement of the instrument thus pushes the sigmoid colon upward, causing unwanted angling.

Fig. 6.6 Sigmoid colon. Normal, distinct vascular pattern.

Fig. 6.7 a, b Sigmoid colon. Normal, round, or oval-shaped lumen.

Fig. 6.8 Haustrations in the sigmoid colon. The curving sigmoid colon makes viewing the inside of the curves difficult.

Fig. 6.9 Winding sigmoid

Fig. 6.10 Sigmoid-descending junction. Sharp angling, folded-over appearance.

Normal Descending Colon

The descending colon runs relatively straight along the left flank from the sigmoid-descending junction to the splenic flexure. Around 20-30 cm long, it is fixed on its posterior side to the dorsal abdominal wall; ventrally it is covered by the peritoneum lining the abdominal cavity. Due to its retroperitoneal fixation, the descending colon is barely mobile, unlike the sigmoid colon and the transverse colon.

The descending colon runs relatively straight along the left flank from the sigmoid-descending junction to the splenic flexure. Around 20-30 cm long, it is fixed on its posterior side to the dorsal abdominal wall; ventrally it is covered by the peritoneum lining the abdominal cavity. Due to its retroperitoneal fixation, the descending colon is barely mobile, unlike the sigmoid colon and the transverse colon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

As in the rest of the colon, the rectal mucosa is smooth and reflective; the blood vessels are clearly visible and easily distinguished from the surrounding surface. As a rule, the vessels in the rectum are more prominent than in the rest of the colon. This is especially true of the venous vessels connected with the vessel branches in the region of the anal canal (hemorrhoidal plexus). The vessels range from pronounced, but still normal, submucosal veins, to pathologically widened veins (e.g., in the case of pronounced hemorrhoidal disease), to rectal varices (e.g., related to portal hypertension,

As in the rest of the colon, the rectal mucosa is smooth and reflective; the blood vessels are clearly visible and easily distinguished from the surrounding surface. As a rule, the vessels in the rectum are more prominent than in the rest of the colon. This is especially true of the venous vessels connected with the vessel branches in the region of the anal canal (hemorrhoidal plexus). The vessels range from pronounced, but still normal, submucosal veins, to pathologically widened veins (e.g., in the case of pronounced hemorrhoidal disease), to rectal varices (e.g., related to portal hypertension,  6.1).

6.1).

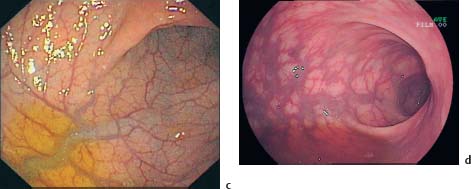

The mucosa is shiny and smooth and the blood vessels clearly visible, though less prominent than in the rectum (

The mucosa is shiny and smooth and the blood vessels clearly visible, though less prominent than in the rectum (