Increasing life expectancy in developed countries has led to a growing prevalence of arthritic disorders, which has been accompanied by increasing prescriptions for nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These are the most widely used agents for musculoskeletal and arthritic conditions. Although NSAIDs are effective, their use is associated with a broad spectrum of adverse reactions in the liver, kidney, cardiovascular system, skin, and gut. Gastrointestinal (GI) side effects are the most common. The dilemma for the physician prescribing NSAIDs is, therefore, to maintain the antiinflammatory and analgesic benefits, while reducing or preventing GI side effects. The challenge is to develop safer NSAIDs by shifting from a focus on GI toxicity to the increasingly more appreciated cardiovascular toxicity.

Increasing life expectancy in developed countries has led to a growing prevalence of arthritic disorders, which has been accompanied by increasing prescriptions for nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These are the most widely used agents for musculoskeletal and arthritic conditions, representing more than 7.7% of all prescriptions in Europe. However, these figures are probably underestimated, because over-the-counter (OTC) use is not included. In absolute terms, in 2004, there were 111 million NSAID prescriptions in the United States. The reason for such widespread use is the clinical effectiveness of NSAIDs, which have been consistently shown to be more effective than acetaminophen (paracetamol) for the management of osteoarthritis (OA), and the fact that NSAIDs are endorsed in current OA management guidelines.

Although NSAIDs are effective, their use is associated with a broad spectrum of adverse reactions in the liver, kidney, cardiovascular (CV) system, skin, and gut. Gastrointestinal (GI) side effects are the most common and range from dyspepsia, heartburn, and abdominal discomfort to more serious events such as peptic ulcer with the life-threatening complications of bleeding and perforation. The dilemma for the physician prescribing NSAIDs is, therefore, to maintain the antiinflammatory and analgesic benefits, while reducing or preventing GI side effects.

NSAIDs are usually given orally, although intravenous, intramuscular, rectal, or topical administrations are used if specifically designed formulations are available. With the exception of renal colic, in which NSAIDs act faster when given intravenously, in all other pain conditions there is no evidence that injected NSAIDs are superior to oral.

Despite the oral route being the most widely used, and allowing self-medication, it is the most challenging in terms of absorption and drug- and food-drug interactions. Moreover, oral intake allows direct contact between the drug and the entire GI tract mucosa, thus exposing it to topical damage until absorption. However, injury may continue after drug absorption if the mucosa is further exposed as a result of enterohepatic circulation of the NSAID.

The GI tract, like the skin and the respiratory system, is in continuous and direct interaction with the environment. The functions of the GI tract as a protective barrier are as important as digestion and absorption. The large surface area and prolonged exposure increase the risk of drug-mediated damage, and increased permeability (often found in some inflammatory conditions) may augment this. The remarkable tolerance of the GI mucosa to damaging agents including NSAIDs relies on rapid epithelial repair, which depends on restitution and cell replication. When repair fails, erosions and ulcers develop, disrupting the basement membrane, forming persistent ulcers, which then increase the risk of clinically relevant events.

Epidemiology of NSAID-associated mucosal injury

In the United States, a national prescription audit showed an annual NSAID consumption of 111,400,000 at a cost of $4.8 billion, with further sales of OTC oral analgesics of $3 billion. A survey of NSAID use among people older than 65 years showed that 70% were taking an NSAID at least once a week and half of these were taking an NSAID daily. A study in Europe reported an NSAID consumption of 42.82 to 74.17 defined daily dose/1000 inhabitants in 2007, increasing by 25.1% between 2002 and 2007. Diclofenac and ibuprofen were the most prescribed agents, with a notable increase in nimesulide and meloxicam use. Trends for consumption of selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors differed within countries.

Recent data from US veterans older than 65 years shows an overall mortality of 5.5 per 1000 person years after an upper GI event, rising to 17.7 per 1000 person years following a myocardial infarction and 21.8 per 1000 person years following a cardiovascular accident. Predictors of mortality were advancing age, comorbidities, increased COX-2 inhibitor use, and failure to provide gastroprotection.

In the United Kingdom, a previous study reported an overall mortality in patients with GI bleeding of 12%. A more recent systematic review of studies published since 1997 shows that upper GI bleeding or perforation still carries a finite risk of death. Differences in study design, population characteristics, risk factors, definition of mortality, and reporting of outcomes imposes limitations on interpreting effect size. Data published since 1997 suggest that mortality in patients suffering from an upper GI bleed or perforation has fallen to 1 in 13 overall, but remains higher, at about 1 in 5, in those exposed to NSAIDs or aspirin.

There have also been serious consequences to the post-Vioxx anxieties about the use of COX-2 selective drugs. There has been a move back to the use of nonselective NSAIDs (ns-NSAIDs) by rheumatologists in North America. A recent study has shown that COX-2 inhibitor withdrawals also resulted in a rapid decline in NSAID gastroprotection prescribed by US rheumatologists despite the availability of different gastroprotective options. Channeling toward nonselective NSAID use was widespread, also among patients at increased CV risk. Longer-term follow-up is required to determine the clinical significance of these changes in NSAID prescribing, particularly for NSAID-related GI and CV-related toxicities.

There has also been a changing pattern to the location of GI bleeding in patients taking NSAIDs, with increasing reports of bleeding lesions located in the small intestine. However, it is not yet clear whether this reflects increased awareness and ascertainment bias or a real increase in small bowel lesions. A study of hospitalized patients in Spain shows that, in the past decade, there has been a progressive change in the overall picture of GI events leading to hospitalization, with a decreasing trend in upper GI events and a significant increase in lower GI events, causing the rates of these GI complications to converge. Overall mortality has also decreased, but the in-hospital case fatality rate from upper or lower GI complications has remained constant. It will be a challenge to improve care unless new strategies can be developed to reduce the number of events originating in the lower GI tract, as well as reducing associated mortality.

The high risk in elderly patients taking NSAIDs has been repeatedly confirmed, and a study from Argentina in 324 adults with a mean age of 74 years and a similar number of controls found that NSAID exposure increased the risk of hospitalization for peptic ulcer disease (PUD, odds ratio [OR] 5.20; 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.31–8.15). A history of upper GI complications was independently associated with hospitalization for PUD (OR 14.62; 95% CI 6.70–31.91). Thus, ns-NSAIDs are a significant risk factor for PUD-related hospitalizations among older adults.

The use of all medications increases with age and the elderly are at increased risk of adverse drug reactions. The risk of these complications depends on the presence of risk factors, the most frequent and relevant of which is age. Thus, patients at risk should be on prevention strategies including the lowest effective dose of NSAID, cotherapy with a gastroprotective drug, or the use of a COX-2 selective agent. Although the best strategy to prevent lower GI complications has yet to be defined, treatment of associated Helicobacter pylori infection is also important when starting treatment with ns-NSAIDs or aspirin, especially in the presence of an ulcer history.

A recent study exploring gastroprotective strategies among 1.5 million patients in the AGIS database indicated that both the prevalence of NSAID prescriptions and the risk of gastric complications is increasing steadily. Although the number of patients receiving gastroprotective medication increased from 39.6% in 2001 to 69.9% in 2007, more than 30% of patients at risk for GI complications were left unprotected in 2007. To enhance protection rates in patients using NSAIDs and to decrease NSAID-related hospital admissions in the future, the implementation of gastroprotection guidelines needs to be improved.

NSAID-associated mucosal damage to the GI tract

NSAID-associated Esophageal Injury

NSAIDs may cause damage throughout the GI tract. Although the stomach and duodenum are well-recognized sites of damage, esophageal injury is common. Despite esophageal mucosa possessing several intrinsic mechanisms of epithelial defense and an efficient clearing system, nearly 100 medications have been implicated as causes of esophageal mucosal damage. Of 92 patients with pill-induced esophageal injury, NSAIDs were causative in 41% (38 of 92) of them. The prevalence of esophagitis in patients with arthritis taking NSAIDs was 21%, and a case-control study indicated that, together with hiatal hernia, NSAID intake represents a significant ( P = .021) risk factor (OR 1.87; 95% CI 1.10–3.19) for esophageal ulcer.

Retrosternal or substernal chest pain is the most common complaint in patients with pill esophagitis, and is present in more than 60% of cases, occurring immediately or several hours after ingestion of medication. Other common complaints are odynophagia and dysphagia, which are present in 50% and 40% of patients, respectively. Symptoms usually develop within the first few days of starting a new medication, but frequently occur with the first dose. If left unrecognized and NSAID intake persists, the acute injury can be complicated by esophageal bleeding, stricture, and even fatal perforation. Drug-induced esophageal injury tends to occur at the anatomic site of narrowing, with the middle third behind the left atrium predominating (75.6%). At endoscopy, erosions, kissing ulcers, and multiple areas of ulceration with bleeding may be seen. The presence of exudates with thickening of the esophageal wall suggests a chemical esophagitis. Moreover, 50% of patients with acute necrotizing esophagitis, a previously considered rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), had taken NSAIDs.

NSAID-associated Gastroduodenal Symptoms and Lesions

The 2 most common causes of PUD are infection with H pylori and use of NSAIDs. The term NSAID gastropathy was first introduced in 1986 to differentiate between classic PUD and the unique range of gastric mucosal lesions associated with long-term NSAID therapy. However, because NSAIDs also damage duodenal mucosa, NSAID-induced gastroduodenal damage is a more appropriate term to describe NSAID-associated lesions. This definition encompasses the true ulcers, which are mucosal lesions that penetrate the muscularis mucosa, and the erosions that are limited to the mucosa. Injury from NSAIDs usually occurs within the first few weeks of treatment but also seems to be associated with long-term use. Upper GI symptoms associated with NSAID use include dyspepsia, heartburn, bloating or cramping, nausea, and vomiting in up to 40% to 50% of patients taking NSAIDs. These symptoms prompt a change in therapy in 10% of patients. However, symptoms associated with NSAIDs have little relationship to erosions or ulcerations seen endoscopically, which are often asymptomatic, and patients with symptoms often have no identifiable lesions. The first sign of NSAID-induced GI damage in asymptomatic individuals may be a life-threatening complication.

Endoscopic examination of NSAID users can reveal subepithelial hemorrhages, erosions, and ulceration, or a combination. Mucosal damage is seen in 30% to 50% of patients taking NSAIDs, but most lesions are of little clinical significance and disappear or reduce in number with continued use, probably because of mucosal adaptation. Only 15% to 30% of NSAIDs users have endoscopically confirmed ulcers, with the gastric antrum being the most frequently affected.

GI complications occur in 1% to 1.5% of patients in the first year of treatment with ns-NSAIDs and, when symptomatic ulcers are included, this figure increases to 4% to 5%. The average relative risk of developing a serious GI complication is three- to fivefold greater among NSAIDs users than among non users. Aspirin is also associated with both gastric and duodenal ulcers, and upper GI complications occur even with the lowest dose of 75 mg/d. Although some studies suggest that the first 2 months of treatment is the period of greatest risk for complications, with a relative risk of 4.5% (95% CI 2.9–7.0), evidence from both randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and observational studies indicate that the risk of GI complications is present with both short-term and long-term use of ns-NSAIDs from the first dose. Thus, even a short course of NSAID therapy (eg, for postoperative pain or acute musculoskeletal injury) carries a risk equivalent to that of long-term treatment. Thus, strategies to prevent GI complications should be implemented regardless of the duration of therapy, especially in patients at high GI risk.

The worst GI outcome with NSAIDs is UGIB, which may result in death. However, mortality data associated with NSAIDs are scarce. Current mortality incidence was estimated at 15.3 deaths per 100,000 among NSAID/aspirin users in a large Spanish study. This mortality is lower than previously quoted, likely because of a decline in the rate of complications in the last 5 to 10 years associated with increasing use of prevention strategies for NSAID-induced GI damage and a decline in the prevalence of H pylori infection.

COX-2 selective NSAIDs (often incorrectly referred to as coxibs ) have an improved upper GI safety profile compared with traditional (nonselective) NSAIDs, as extensively shown in endoscopy and clinical outcomes studies. The evidence is strong, with consistent reductions in events of about 50% in large RCTs, meta-analyses of RCTs, and large observational studies in clinical practice.

The prevalence of dyspepsia in users of ns-NSAIDs and COX-2 selective inhibitors was examined in a meta-analysis of 26 RCTs, which revealed a 12% relative risk reduction in dyspeptic symptoms for COX-2 selective versus ns-NSAIDs. Compared with ns-NSAIDs, the number needed to treat with a COX-2 inhibitor to prevent 1 patient from developing dyspepsia was 27. Dyspepsia reduction with COX-2 inhibitor therapy may not be substantial, and patients on COX-2 selective NSAIDs may need cotherapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to obtain the same symptom improvement as those taking ns-NSAIDs. However, experience indicates that, in the individual patient, the lower dyspepsia rate with coxibs compared with ns-NSAIDs, although not large, could be clinically relevant.

Large outcome studies, as well as endoscopic and epidemiologic studies, confirm that low-dose aspirin (LD-ASA) increases the risk of UGIB in NSAID and COX-2 inhibitor users and attenuates the GI benefits of COX-2 selective NSAIDs. A COX-2 inhibitor plus aspirin was associated with a nonsignificantly lower ulcer and lower ulcer complication rate when compared with ns-NSAIDs alone. Moreover, a COX-2 inhibitor plus LD-ASA was associated with lower GI risk than an ns-NSAID plus LD-ASA. Thus, combination of aspirin plus a COX-2 inhibitor should be the preferred option, compared with aspirin plus an ns-NSAID, for patients at high GI risk who require CV prophylaxis. Future RCTs, specifically designed to compare the GI and CV safety of a COX-2 inhibitor plus aspirin and an ns-NSAID plus aspirin, are needed to confirm these conclusions.

NSAID-associated Bowel Injury

The small bowel is more common than the stomach as a site for adverse effects of NSAIDs, producing NSAID enteropathy. The pathogenesis and clinical implications of adverse effects at the two sites have many similarities but differ in some important aspects. NSAID enteropathy, rather than being life threatening, often leads to complications that call for extensive investigation, and needs to be differentiated from other newly discovered enteropathies. In particular, a common problem is to distinguish between ileitis in association with spondyloarthropathy, NSAID enteropathy, and Crohn disease. Moreover, the frequency of life-threatening complications in the lower GI tract represent one-third of all GI complications associated with NSAIDs. In the last 10 years, there has been a decreasing trend in hospitalizations because of upper GI complications, in contrast with an increasing trend of lower GI complications, and the clinical effect and severity of lower GI events were greater than for upper GI events.

Most patients with NSAID enteropathy are asymptomatic and can be diagnosed by demonstrating increased intestinal permeability, increased fecal calprotectin, or by wireless capsule enteroscopy. However, the capsule findings (mucosal breaks, reddened folds, petechiae or red spots, denuded mucosa, and blood in the lumen without a visualized source) are not pathognomonic for NSAID injury, and similar changes are seen in a variety of small bowel diseases. In particular, it is sometimes impossible to differentiate NSAID enteropathy from that of Crohn disease. The most common indication leading to a diagnosis of NSAID enteropathy is iron deficiency anemia. Endoscopy and colonoscopy may fail to provide an adequate explanation for the anemia, and capsule enteroscopy is likely to provide a diagnosis when luminal blood may be evident.

The spectrum of abnormalities that are detected range from subclinical damage, including increased mucosal permeability, mucosal inflammation, fecal occult blood loss, ileal dysfunction, and malabsorption, to clinical features including anemia, mucosal diaphragms and strictures, small bowel, colonic, and rectal ulceration, colitis, as well as bleeding and perforation. Increased mucosal permeability is silent and observed within 24 hours of ingestion with almost all NSAIDs, except the coxibs and ns-NSAIDs not undergoing enterohepatic recirculation.

The lack of intestinal damage with selective COX-2 inhibitors seen in animal experiments has been confirmed in clinical studies. Most patients taking either meloxicam or nimesulide, two preferential COX-2 inhibitors, had normal intestinal permeability and no increase in intestinal inflammation compared with control patients. In studies in healthy volunteers, rofecoxib and etoricoxib, compared with the ns-NSAID, ibuprofen, did not increase fecal blood loss. Furthermore, the incidence of anemia with celecoxib was significantly less than that seen with ns-NSAIDs. Although some case reports of acute colitis or lower intestinal complications have been associated with COX-2 inhibitors, post hoc analysis of the Vioxx GI Outcomes Research (VIGOR) study showed that the benefits of rofecoxib 50 mg/d compared with naproxen (500 mg twice a day) were present in both the upper and the lower GI tract, with a risk reduction for serious lower GI events of 50% and 60%, respectively. In the recent CONDOR study, comparing celecoxib with slow-release diclofenac plus omeprazole, celecoxib was superior to the NSAID plus PPI in reducing the risk of clinical outcomes throughout the GI tract. The study used as primary end point a novel composite score (clinically significant upper and/or lower gastrointestinal events [CSULGIEs]), which is discussed later. Etoricoxib, which is an acidic (pK a 4.5) COX-2 selective compound, did not achieve a significant decrease in lower GI clinical events compared with diclofenac in the RCTs belonging to the Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term (MEDAL) program.

Colonoscopy studies confirm that NSAIDs are associated with isolated and diffuse colonic ulceration that may be associated with occult or major intestinal bleeding and/or perforation. Diffuse colitis has been observed after mefenamic acid, ibuprofen, piroxicam, naproxen, and aspirin. NSAID colopathy (ulceration or stricture formation) usually involves the right colon, but the rectum may also be involved. Patients may present with diarrhea, bleeding, anemia, weight loss, or obstruction. Ileoscopy may show an ulcerative ileitis, whose features overlap with Crohn ileitis, but differentiation is critical for appropriate management. Although some patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can tolerate NSAIDs, they may reactivate quiescent disease , exacerbate preexisting lesions, including colonic diverticula, and trigger intestinal bleeding from angiodysplasia lesions.

Coxibs also seem to be better tolerated in the colon than ns-NSAIDs. A retrospective study reported the long-term (median 9 months) safety of these agents in patients with IBD, whereas 2 prospective, placebo-controlled studies with celecoxib or etoricoxib did not show any significant increase in relapse rate, at least in the short-term.

NSAID-associated mucosal damage to the GI tract

NSAID-associated Esophageal Injury

NSAIDs may cause damage throughout the GI tract. Although the stomach and duodenum are well-recognized sites of damage, esophageal injury is common. Despite esophageal mucosa possessing several intrinsic mechanisms of epithelial defense and an efficient clearing system, nearly 100 medications have been implicated as causes of esophageal mucosal damage. Of 92 patients with pill-induced esophageal injury, NSAIDs were causative in 41% (38 of 92) of them. The prevalence of esophagitis in patients with arthritis taking NSAIDs was 21%, and a case-control study indicated that, together with hiatal hernia, NSAID intake represents a significant ( P = .021) risk factor (OR 1.87; 95% CI 1.10–3.19) for esophageal ulcer.

Retrosternal or substernal chest pain is the most common complaint in patients with pill esophagitis, and is present in more than 60% of cases, occurring immediately or several hours after ingestion of medication. Other common complaints are odynophagia and dysphagia, which are present in 50% and 40% of patients, respectively. Symptoms usually develop within the first few days of starting a new medication, but frequently occur with the first dose. If left unrecognized and NSAID intake persists, the acute injury can be complicated by esophageal bleeding, stricture, and even fatal perforation. Drug-induced esophageal injury tends to occur at the anatomic site of narrowing, with the middle third behind the left atrium predominating (75.6%). At endoscopy, erosions, kissing ulcers, and multiple areas of ulceration with bleeding may be seen. The presence of exudates with thickening of the esophageal wall suggests a chemical esophagitis. Moreover, 50% of patients with acute necrotizing esophagitis, a previously considered rare cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB), had taken NSAIDs.

NSAID-associated Gastroduodenal Symptoms and Lesions

The 2 most common causes of PUD are infection with H pylori and use of NSAIDs. The term NSAID gastropathy was first introduced in 1986 to differentiate between classic PUD and the unique range of gastric mucosal lesions associated with long-term NSAID therapy. However, because NSAIDs also damage duodenal mucosa, NSAID-induced gastroduodenal damage is a more appropriate term to describe NSAID-associated lesions. This definition encompasses the true ulcers, which are mucosal lesions that penetrate the muscularis mucosa, and the erosions that are limited to the mucosa. Injury from NSAIDs usually occurs within the first few weeks of treatment but also seems to be associated with long-term use. Upper GI symptoms associated with NSAID use include dyspepsia, heartburn, bloating or cramping, nausea, and vomiting in up to 40% to 50% of patients taking NSAIDs. These symptoms prompt a change in therapy in 10% of patients. However, symptoms associated with NSAIDs have little relationship to erosions or ulcerations seen endoscopically, which are often asymptomatic, and patients with symptoms often have no identifiable lesions. The first sign of NSAID-induced GI damage in asymptomatic individuals may be a life-threatening complication.

Endoscopic examination of NSAID users can reveal subepithelial hemorrhages, erosions, and ulceration, or a combination. Mucosal damage is seen in 30% to 50% of patients taking NSAIDs, but most lesions are of little clinical significance and disappear or reduce in number with continued use, probably because of mucosal adaptation. Only 15% to 30% of NSAIDs users have endoscopically confirmed ulcers, with the gastric antrum being the most frequently affected.

GI complications occur in 1% to 1.5% of patients in the first year of treatment with ns-NSAIDs and, when symptomatic ulcers are included, this figure increases to 4% to 5%. The average relative risk of developing a serious GI complication is three- to fivefold greater among NSAIDs users than among non users. Aspirin is also associated with both gastric and duodenal ulcers, and upper GI complications occur even with the lowest dose of 75 mg/d. Although some studies suggest that the first 2 months of treatment is the period of greatest risk for complications, with a relative risk of 4.5% (95% CI 2.9–7.0), evidence from both randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and observational studies indicate that the risk of GI complications is present with both short-term and long-term use of ns-NSAIDs from the first dose. Thus, even a short course of NSAID therapy (eg, for postoperative pain or acute musculoskeletal injury) carries a risk equivalent to that of long-term treatment. Thus, strategies to prevent GI complications should be implemented regardless of the duration of therapy, especially in patients at high GI risk.

The worst GI outcome with NSAIDs is UGIB, which may result in death. However, mortality data associated with NSAIDs are scarce. Current mortality incidence was estimated at 15.3 deaths per 100,000 among NSAID/aspirin users in a large Spanish study. This mortality is lower than previously quoted, likely because of a decline in the rate of complications in the last 5 to 10 years associated with increasing use of prevention strategies for NSAID-induced GI damage and a decline in the prevalence of H pylori infection.

COX-2 selective NSAIDs (often incorrectly referred to as coxibs ) have an improved upper GI safety profile compared with traditional (nonselective) NSAIDs, as extensively shown in endoscopy and clinical outcomes studies. The evidence is strong, with consistent reductions in events of about 50% in large RCTs, meta-analyses of RCTs, and large observational studies in clinical practice.

The prevalence of dyspepsia in users of ns-NSAIDs and COX-2 selective inhibitors was examined in a meta-analysis of 26 RCTs, which revealed a 12% relative risk reduction in dyspeptic symptoms for COX-2 selective versus ns-NSAIDs. Compared with ns-NSAIDs, the number needed to treat with a COX-2 inhibitor to prevent 1 patient from developing dyspepsia was 27. Dyspepsia reduction with COX-2 inhibitor therapy may not be substantial, and patients on COX-2 selective NSAIDs may need cotherapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to obtain the same symptom improvement as those taking ns-NSAIDs. However, experience indicates that, in the individual patient, the lower dyspepsia rate with coxibs compared with ns-NSAIDs, although not large, could be clinically relevant.

Large outcome studies, as well as endoscopic and epidemiologic studies, confirm that low-dose aspirin (LD-ASA) increases the risk of UGIB in NSAID and COX-2 inhibitor users and attenuates the GI benefits of COX-2 selective NSAIDs. A COX-2 inhibitor plus aspirin was associated with a nonsignificantly lower ulcer and lower ulcer complication rate when compared with ns-NSAIDs alone. Moreover, a COX-2 inhibitor plus LD-ASA was associated with lower GI risk than an ns-NSAID plus LD-ASA. Thus, combination of aspirin plus a COX-2 inhibitor should be the preferred option, compared with aspirin plus an ns-NSAID, for patients at high GI risk who require CV prophylaxis. Future RCTs, specifically designed to compare the GI and CV safety of a COX-2 inhibitor plus aspirin and an ns-NSAID plus aspirin, are needed to confirm these conclusions.

NSAID-associated Bowel Injury

The small bowel is more common than the stomach as a site for adverse effects of NSAIDs, producing NSAID enteropathy. The pathogenesis and clinical implications of adverse effects at the two sites have many similarities but differ in some important aspects. NSAID enteropathy, rather than being life threatening, often leads to complications that call for extensive investigation, and needs to be differentiated from other newly discovered enteropathies. In particular, a common problem is to distinguish between ileitis in association with spondyloarthropathy, NSAID enteropathy, and Crohn disease. Moreover, the frequency of life-threatening complications in the lower GI tract represent one-third of all GI complications associated with NSAIDs. In the last 10 years, there has been a decreasing trend in hospitalizations because of upper GI complications, in contrast with an increasing trend of lower GI complications, and the clinical effect and severity of lower GI events were greater than for upper GI events.

Most patients with NSAID enteropathy are asymptomatic and can be diagnosed by demonstrating increased intestinal permeability, increased fecal calprotectin, or by wireless capsule enteroscopy. However, the capsule findings (mucosal breaks, reddened folds, petechiae or red spots, denuded mucosa, and blood in the lumen without a visualized source) are not pathognomonic for NSAID injury, and similar changes are seen in a variety of small bowel diseases. In particular, it is sometimes impossible to differentiate NSAID enteropathy from that of Crohn disease. The most common indication leading to a diagnosis of NSAID enteropathy is iron deficiency anemia. Endoscopy and colonoscopy may fail to provide an adequate explanation for the anemia, and capsule enteroscopy is likely to provide a diagnosis when luminal blood may be evident.

The spectrum of abnormalities that are detected range from subclinical damage, including increased mucosal permeability, mucosal inflammation, fecal occult blood loss, ileal dysfunction, and malabsorption, to clinical features including anemia, mucosal diaphragms and strictures, small bowel, colonic, and rectal ulceration, colitis, as well as bleeding and perforation. Increased mucosal permeability is silent and observed within 24 hours of ingestion with almost all NSAIDs, except the coxibs and ns-NSAIDs not undergoing enterohepatic recirculation.

The lack of intestinal damage with selective COX-2 inhibitors seen in animal experiments has been confirmed in clinical studies. Most patients taking either meloxicam or nimesulide, two preferential COX-2 inhibitors, had normal intestinal permeability and no increase in intestinal inflammation compared with control patients. In studies in healthy volunteers, rofecoxib and etoricoxib, compared with the ns-NSAID, ibuprofen, did not increase fecal blood loss. Furthermore, the incidence of anemia with celecoxib was significantly less than that seen with ns-NSAIDs. Although some case reports of acute colitis or lower intestinal complications have been associated with COX-2 inhibitors, post hoc analysis of the Vioxx GI Outcomes Research (VIGOR) study showed that the benefits of rofecoxib 50 mg/d compared with naproxen (500 mg twice a day) were present in both the upper and the lower GI tract, with a risk reduction for serious lower GI events of 50% and 60%, respectively. In the recent CONDOR study, comparing celecoxib with slow-release diclofenac plus omeprazole, celecoxib was superior to the NSAID plus PPI in reducing the risk of clinical outcomes throughout the GI tract. The study used as primary end point a novel composite score (clinically significant upper and/or lower gastrointestinal events [CSULGIEs]), which is discussed later. Etoricoxib, which is an acidic (pK a 4.5) COX-2 selective compound, did not achieve a significant decrease in lower GI clinical events compared with diclofenac in the RCTs belonging to the Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term (MEDAL) program.

Colonoscopy studies confirm that NSAIDs are associated with isolated and diffuse colonic ulceration that may be associated with occult or major intestinal bleeding and/or perforation. Diffuse colitis has been observed after mefenamic acid, ibuprofen, piroxicam, naproxen, and aspirin. NSAID colopathy (ulceration or stricture formation) usually involves the right colon, but the rectum may also be involved. Patients may present with diarrhea, bleeding, anemia, weight loss, or obstruction. Ileoscopy may show an ulcerative ileitis, whose features overlap with Crohn ileitis, but differentiation is critical for appropriate management. Although some patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can tolerate NSAIDs, they may reactivate quiescent disease , exacerbate preexisting lesions, including colonic diverticula, and trigger intestinal bleeding from angiodysplasia lesions.

Coxibs also seem to be better tolerated in the colon than ns-NSAIDs. A retrospective study reported the long-term (median 9 months) safety of these agents in patients with IBD, whereas 2 prospective, placebo-controlled studies with celecoxib or etoricoxib did not show any significant increase in relapse rate, at least in the short-term.

NSAID users: who is at risk of GI complications?

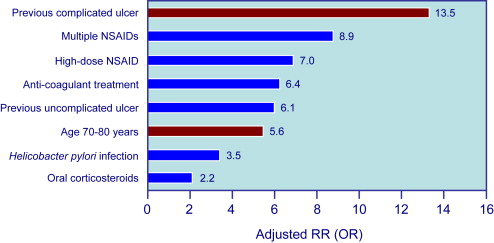

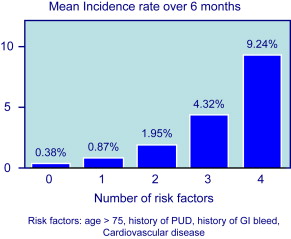

Because symptoms are not a reliable indicator of mucosal damage, it is important to identify factors that increase the risk of GI events in NSAID users. Risk factors for UGIB associated with NSAID use are well defined by several studies and are summarized in Fig. 1 . The most important are age and prior history of complicated ulcer. Older age is common in NSAID users, and those older than 70 years carry a risk similar to those with a history of peptic ulcer. Advancing age increases risk by about 4% per year, probably because of the presence of other associated risk factors. The role of H pylori infection in patients taking NSAIDs, and the potential benefit of eradication on upper GI risk in infected NSAIDs users, has been controversial. A meta-analysis of case-control studies showed synergism for the development of complicated and uncomplicated ulcer between H pylori infection and NSAIDs. H pylori is also a risk factor in LD-ASA users, and a post hoc analysis of the VIGOR trial suggested that the GI benefits of coxibs are lower in patients with the infection than in those without. Concomitant aspirin use increases the risk of GI events in patients taking ns-NSAIDs or selective COX-2 inhibitors. The presence of multiple risk factors greatly increases the risk of GI complications. When combinations of these risk factors are considered, the logistic regression model predicts that, in 6 months, patients with none of the 4 factors considered (age>75 years, history of PUD, history of GI bleed, CV disease) have a risk for having one of the defined GI complications of only 0.4%, patients with any single factor, a risk of 0.9%, and patients with all 4 factors, a risk of 9% ( Fig. 2 ).

Mechanisms of mucosal injury

General Pharmacology and Physicochemical Properties of NSAIDs

For more than 100 years, analgesic agents have been integral to the management of musculoskeletal disorders. The clinical benefits and adverse effects of aspirin, indomethacin, phenylbutazone, and the newer propionic acid drugs were well established by the end of the 1960s, but it was only after 1971 that the late Professor Sir John Vane established the key mechanism of action of NSAIDs as inhibitors of prostaglandin (PG) synthesis. Neither all the benefits nor untoward reactions are solely caused by inhibition of PG synthesis because weak inhibitors, such as nonacetylated salicylates, are equipotent to aspirin in inflammatory joint disease. Some NSAIDs display a broad spectrum of other pharmacologic activities (eg, inhibition of histamine release from basophils, antioxidant activity, and inhibition of protease release from activated leucocytes), which contribute to both the desirable and undesirable effects of these drugs.

Most NSAIDs are organic acids, which is important for their pharmacokinetics, GI ulcerogenicity, and for certain biochemical actions, especially their potency as PG synthesis inhibitors. However, there are important differences in their physicochemical properties that probably underlie variations in ulcerogenicity. Thus, within NSAID families (eg, salicylates, fenamates, arylacetic acids) there is an interplay between the respective lipophilic (as measured by the partitioning of drugs between organic solvents and water to yield a logP) and acidic properties (pK a ) of these drugs that underlie their gastric ulcerogenicity. Many of the more ulcerogenic drugs (which are also COX-1/COX-2 inhibitors) are carboxylic acids with a low pK a (2.8–4.4) and apparently marked variation in logP values over the range of acidic pH. The potential for acidic NSAIDs to interact with phospholipids causing disruption in both mucosal membranes and the hydrophobic barrier is well established. The differences in physicochemical properties determine the topical irritancy in the GI mucosa and also their systemic bioavailability, especially in relation to protein binding. Thus, the systemic bioavailability in the GI mucosa is expected to contribute to ulcerogenic activity.

The physicochemical properties also underlie the potential for interactions with the active sites of COX-1 and COX-2, respectively. Selective COX-2 inhibitors are different from most ns-NSAIDs, being nonacidic, with much higher pK a values. This major difference may account for the low mucosal irritancy observed with these drugs separately from their lack of or low inhibitory activity on COX-1 in the stomach. Acidic selective COX-2 inhibitors (eg, etoricoxib) increase gastric potential difference (an index of mucosal integrity), whereas nonacidic selective COX-2 inhibitors (eg, celecoxib) do not (Scarpignato and colleagues, unpublished results).

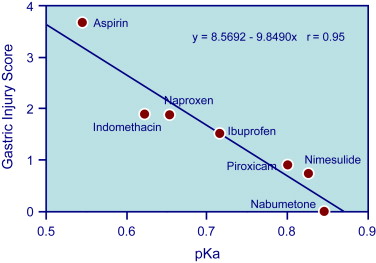

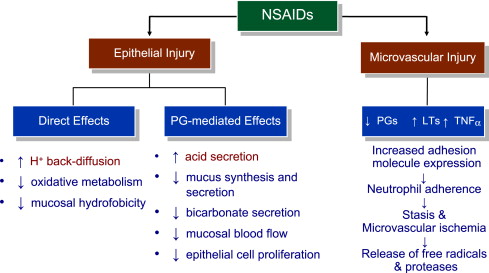

Topical and Systemic Toxicity

Gastroduodenal mucosa possesses many defensive mechanisms and NSAIDs have a deleterious effect on most of them. This results in a mucosa less able to cope with even a reduced acid load. The presence of acid seems to be a conditio sine qua non for NSAID injury, which is pH dependent. Acid injures the mucosa by H + ion back diffusion from the lumen causing tissue acidosis and also increases drug absorption, which is inversely proportional to drug ionization. NSAIDs cause gastroduodenal damage by 2 main mechanisms: a physiochemical disruption of the gastric mucosal barrier and systemic inhibition of gastric mucosal protection, through inhibition of cyclooxygenase (PG endoperoxide G/H synthase, COX) activity of the GI mucosa. A reduced synthesis of mucus and bicarbonate, an impairment of mucosal blood flow, and an increase in acid secretion are the main consequences of NSAID-induced PG deficiency. There is mounting evidence to suggest that gastric damage induced by ns-NSAIDs does not occur because of COX-1 inhibition; dual suppression of COX-1 and COX-2 is necessary for damage. However, against a background of COX inhibition by antiinflammatory doses of NSAIDs, their physicochemical properties, in particular their acidity, underlie the topical effect, leading to short-term damage. Gastric injury (quantitated by Lanza score) correlated significantly with the pK a of the single compound ( Fig. 3 ): the lower the acidity of the drug, the less the mucosal damage.

Additional mechanisms may contribute to damage, including uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation leading to ATP depletion, reduced mucosal cell proliferation and DNA synthesis, as well as neutrophil activation.

NSAID inhibition of the so-called cytoprotective PGs has been regarded as a major factor for mucosal damage. However, diversion of arachidonate through the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway enhances leukotriene (LT) synthesis. These mediators cause vasoconstriction and release oxygen free radicals, which add to damage caused by the impairment of mucosal defense. Enhanced gastric mucosal leukotriene B 4 (LTB 4 ) synthesis is seen in patients taking NSAIDs, corroborating the animal data. A summary of the mechanisms involved in NSAID-associated upper GI mucosal damage is presented in Fig. 4 .

Nitric oxide (NO) and hydrogen sulfide (H 2 S) are endogenously generated gaseous mediators, important in maintaining gastric mucosal integrity, which share many biologic effects with PGs. Evidence suggests that NSAIDs may also induce GI damage by interference with the mucosal synthesis and availability of these mediators.

Being COX-1 sparing, selective COX-2 inhibitors, such as rofecoxib, do not impair gastric mucosal PG synthesis or serum thromboxane A 2 in humans, nor do they affect platelet aggregation and bleeding time. Thus, endoscopy studies show that ulcer incidence with these drugs overlaps that seen with placebo. However, biochemical selectivity is only one of several important determinants of the risk of experiencing a serious GI complication during long-term NSAID therapy. Selective COX-2 inhibitors, besides sparing PG synthesis in the GI mucosa, do not uncouple oxidative phosphorylation, because they are nonacidic, nor do they increase gastric permeability. Therefore, they do not significantly affect these 2 basic biochemical mechanisms of NSAID-induced damage, which accounts for their remarkable GI safety.

The reduction in the gastroduodenal safety of coxibs when given to patients taking aspirin might be caused by the suppression of a class of lipid mediators produced by the interaction of aspirin with the COX-2 isoenzyme, the aspirin-triggered lipoxins (ATLs). ATLs are generated in the gastric mucosa in response to aspirin, and are involved in gastric adaptation to aspirin. Inhibition of COX-2 activity by ns-NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors interferes with the adaptation of the gastric mucosa to aspirin, and exacerbates mucosal injury. Experiments in healthy volunteers suggest that this mechanism operates in the human stomach.

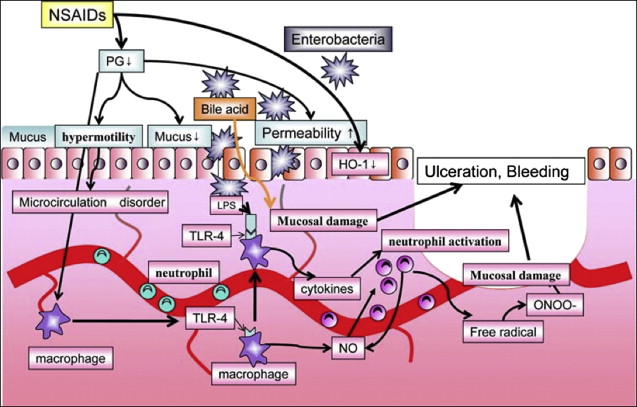

The pathogenesis of small intestinal damage with NSAIDs is less well understood. Although inhibition of mucosal PG synthesis during NSAID use occurs along the entire digestive tract, there are significant differences between the distal and proximal GI tract in the concurrence of other pathogenic factors that may add to mucosal damage. The most evident of these differences are the absence of acid (which plays a pivotal role in upper GI damage) and the presence of bacteria and bile in the intestine, which may trigger specific NSAID-related pathogenic mechanisms in the distal GI tract.

Increasing experimental evidence suggests that inhibition of both COX-1 and COX-2 is necessary to cause significant GI damage. However, NSAID-induced damage to the intestinal epithelium is started by direct effects of the drug after oral administration, a persistent local action caused by enterohepatic recirculation and systemic effects after absorption. Initial cellular damage is caused by the entrance of the usually acidic NSAID into the cell via damage to the brush border cell membrane, and disruption of mitochondrial processes of oxidative phosphorylation, with consequent ATP deficiency. This deficiency leads to increased mucosal permeability, which facilitates entry and actions of luminal factors such as dietary macromolecules, bile acids, components of pancreatic juice, and bacteria, activating the inflammatory cascade.

Among luminal aggressors, intestinal bacteria are the main neutrophil chemoattractants. Several studies show that antimicrobials (tetracycline, kanamycin, metronidazole or neomycin, plus bacitracin) attenuate NSAID enteropathy, further supporting the pathogenic role of enteric bacteria. In addition, indirect support for the role of gut bacteria in the pathogenesis of NSAID enteropathy comes from the similarity between indomethacin-induced intestinal damage and Crohn disease. Not only are the lesions both macro- and microscopically similar, they are also sensitive to the same drugs (eg, sulfasalazine, corticosteroids, immunosuppressives, and antibiotics). The multiple mechanisms involved in the generation of NSAID-associated small bowel injury are shown in Fig. 5 .

NSAID-associated intestinal damage is a pH-independent phenomenon. As a consequence, coadministration of antisecretory drugs is not expected to be able to either prevent or treat mucosal lesions. Video capsule studies show that combination of a PPI with an ns-NSAID does not prevent intestinal damage associated with short-term administration of naproxen or ibuprofen. Celecoxib was better tolerated than ns-NSAIDs by the intestinal mucosa, and was associated with significantly fewer small bowel mucosal breaks than ns-NSAIDs plus PPI.

The lack of acidity (ie, lack of free carboxylic groups) in the celecoxib molecule seems to be an important determinant of GI safety not only in the upper, but also the lower, GI tract. Celecoxib does not increase intestinal permeability or inflammation and does not initiate the sequence of pathophysiologic events leading to mucosal damage with consequent loss of blood and protein.

The Role of Mucosal Inflammation

There is increasing interest in the role of the immune system in regulating the host response to noxious agents. We have recently shown in a mouse model that Th2-predominant Balb/c mice are more susceptible to NSAIDs gastropathy than Th1-predominant C57BL/6 mice and that this is associated with strain-specific PG differences. Moreover, acid secretion in C57BL/6 mice is not inhibited by PGs because they have a fivefold lower expression of EP 3 receptors on the parietal cell compared with Balb/c mice, so that, in the Black/6, acid secretion is unchanged despite inhibition of prostaglandin E 2 by NSAIDs and there is less mucosal damage compared with Balb/c mice. This finding suggests the importance of the host immune response to NSAIDs and potentially offers an alternative explanation for the increased incidence of myocardial infarction seen with both ns-NSAIDs and selective inhibitors of COX-2.

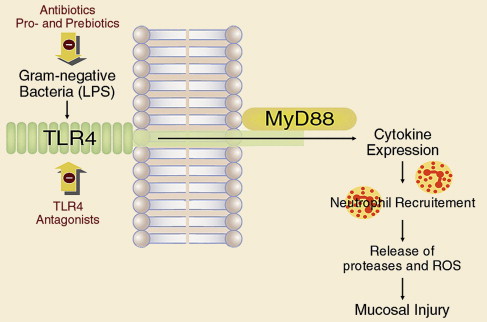

Enterobacteria and the mucosal inflammatory response, involving cellular response and cytokine production, both play their roles in the pathophysiology of NSAID-induced enteropathy. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 recognizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS) expressed by bacteria, which results in activation of an inflammatory cascade, acting through accessory protein MyD88. In a recent study, rats treated with indomethacin were also given the antibiotics ampicillin, aztreonam, or vancomycin orally or intraperitoneal LPS, which is a TLR4 ligand, or neutralizing antibodies against neutrophils, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, or monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1). Intestinal ulcerogenicity of indomethacin was also examined in TLR4-mutant mice. Indomethacin-induced small intestinal damage was associated with the expression of TNF-α and MCP-1. Antibodies against neutrophils, TNF-α, and MCP-1 prevented the damage by 83%, 67%, and 63%, respectively. Ampicillin and aztreonam also inhibited this damage, and decreased the number of gram-negative bacteria in the rat small intestine, but vancomycin showed no activity against bacteria, nor any protective effect. This understanding of how indomethacin may injure the small intestine through a TLR4/MyD88-dependent pathway offers potential new targets for protection ( Fig. 6 ).