Background

Testicular cancer is the most common malignancy in men age 15–35 years old. As a result of therapeutic advances over the past several decades and the integration of multimodal treatment, testicular cancer is now one of the most curable neoplasms. Nonseminomatous germ cell tumor (NSGCT) includes embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, teratoma and yolk sac tumor. Despite favorable long-term survival, the multimodal treatment of NSGCT is constantly evolving and incorporating new paradigms. This chapter aims to present evidence available for several controversies regarding the management of NSGCT.

Clinical question 37.1

How should the violated scrotum be managed?

Literature search

A search of Medline and PubMed databases was conducted to retrieve available publications pertaining to each clinical question. Each database search was limited to articles published between 1960 and 2008 and included only English-language reports. All clinical studies were eligible for inclusion and reports utilizing all levels of evidence were considered for inclusion. The reference list from all included publications was scrutinized to identify potentially relevant publications. Search terms included “testicular neoplasm,” “germ cell tumor,” “scrotal violation,” “trans-scrotal orchiectomy,” “trans-scrotal biopsy” and “postorchiectomy complications.”

The evidence

An inguinal orchiectomy with high ligation of the spermatic cord is the standard of care for managing a testicular mass that is suspicious for neoplasm. While this technique is undisputed, management of the violated scrotum is more controversial. Scrotal violation can occur during scrotal orchiectomy, percutaneous testicular biopsy, percutaneous fine-needle aspiration or inguinal-scrotal orchiectomy. Prior inguinal or scrotal surgery could also alter the normal lymphatic drainage of the testis [1]. Scrotal violation before or during orchiectomy leads to concern for higher rates of local and distant recurrence outside conventional retroperitoneal templates.

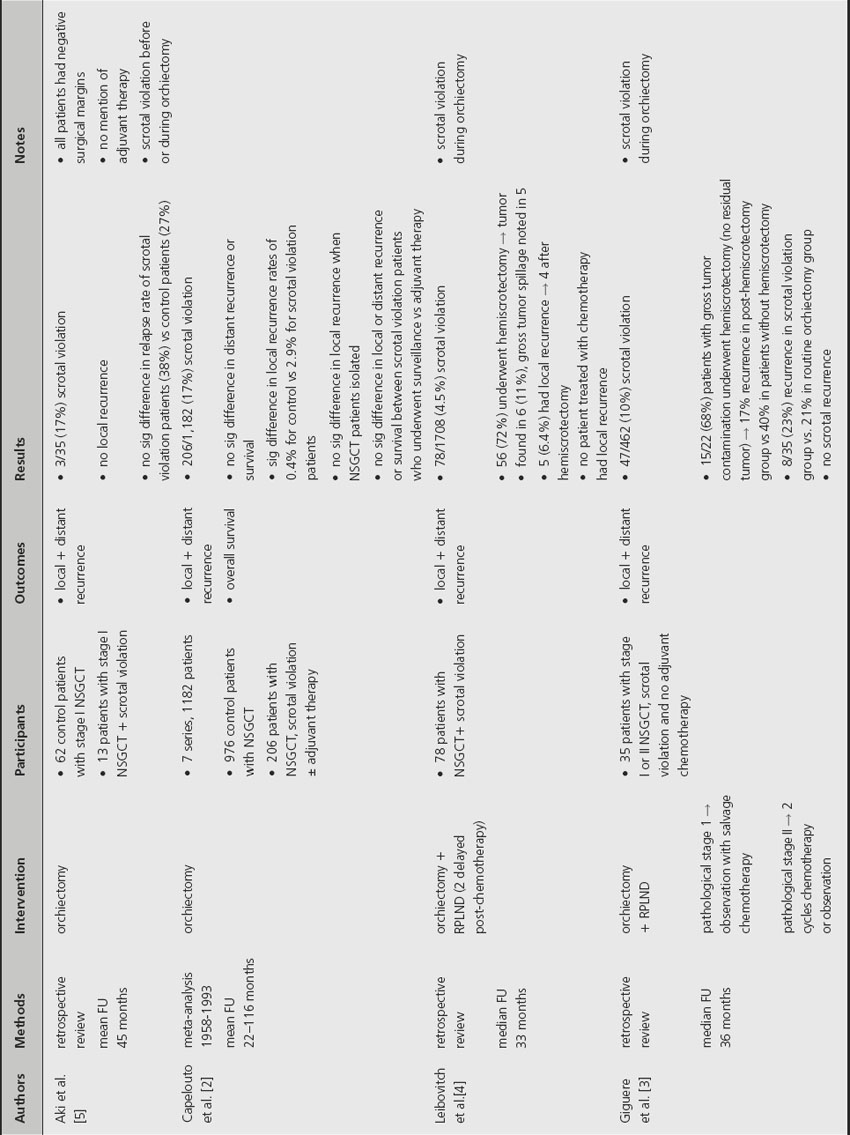

In the past two decades, three retrospective reviews and one meta-analysis have specifically examined the impact of scrotal violation on recurrence in patients with NSGCT (Table 37.1). The incidence of scrotal violation ranges from 5% to 17% [2–4].

Table 37.1 Management of the violated scrotum

A retrospective analysis by Leibovitch et al. noted that 11% of patients who underwent a hemiscrotectomy after scrotal violation were found to have residual tumor and 66% of these patients experienced local recurrence even after local resection [4]. The same study also noted that no patient treated with chemotherapy after scrotal violation experienced local recurrence. A retrospective study by Giguere et al. noted that 68% of patients with scrotal violation underwent hemiscrotectomy and were found to have no residual tumor [3]. Despite the absence of residual tumor, the authors reported a 17% recurrence rate in the group that underwent local excision versus 40% in patients with scrotal violation who did not undergo hemiscrotectomy. A more recent study by Aki et al. found no local recurrence after scrotal violation and no significant difference in recurrence rates between patients with scrotal violation and those who underwent a standard orchiectomy [5]. Of note, all patients included in the study had negative surgical margins after orchiectomy. Despite these favorable results, the authors did not provide information regarding adjuvant treatment for patients with scrotal violation so few conclusions can be drawn from this study.

A meta-analysis by Capelouto et al. examined 206 cases of scrotal violation and found no difference in distant recurrence or survival between patients with scrotal violation and patients who underwent standard orchiectomy [2]. When NSGCT cases were isolated, there was also no significant difference in rates of local recurrence. The analysis also reported no significant difference in local or distant recurrence rates for patients with scrotal violation who received local adjuvant therapy and those who did not receive additional local treatment. The authors did not provide information regarding the presence or absence of residual tumor in hemiscrotectomy specimens.

Comment

The current literature indicates that patients with scrotal violation and clinical stage I NSGCT are not good candidates for surveillance. A conditional recommendation (Grade 2C) can be made to counsel these patients regarding adjuvant chemotherapy or retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) with simultaneous hemiscrotectomy and excision of the spermatic cord remnant. Based on the current low-quality evidence, patients with scrotal violation are not necessarily at higher risk for local or distant recurrence if they receive adjuvant therapy.

Clinical question 37.2

What is the role of laparoscopy in primary RPLND?

Literature search

A Medline and PubMed search was conducted using the previously described methods. Search terms included “testicular neoplasm,” “germ cell tumor,” “laparoscopic RPLND” and “laparoscopic lymphadenectomy.”

The evidence

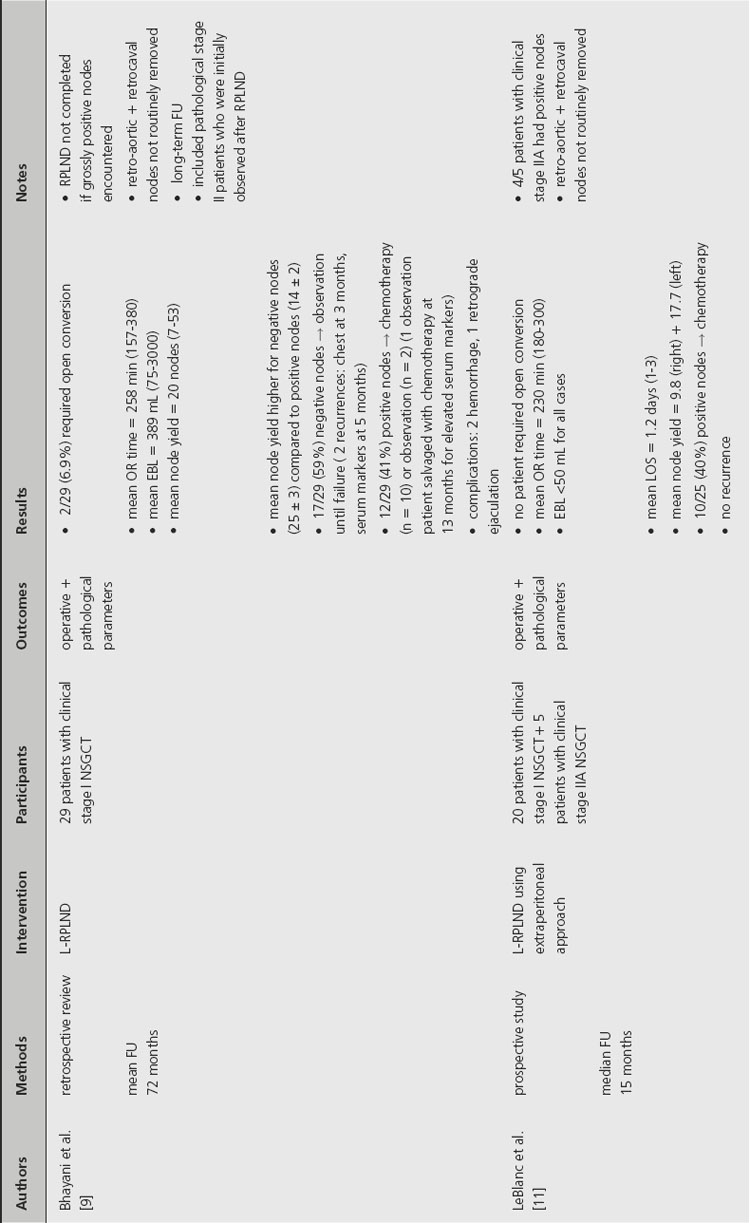

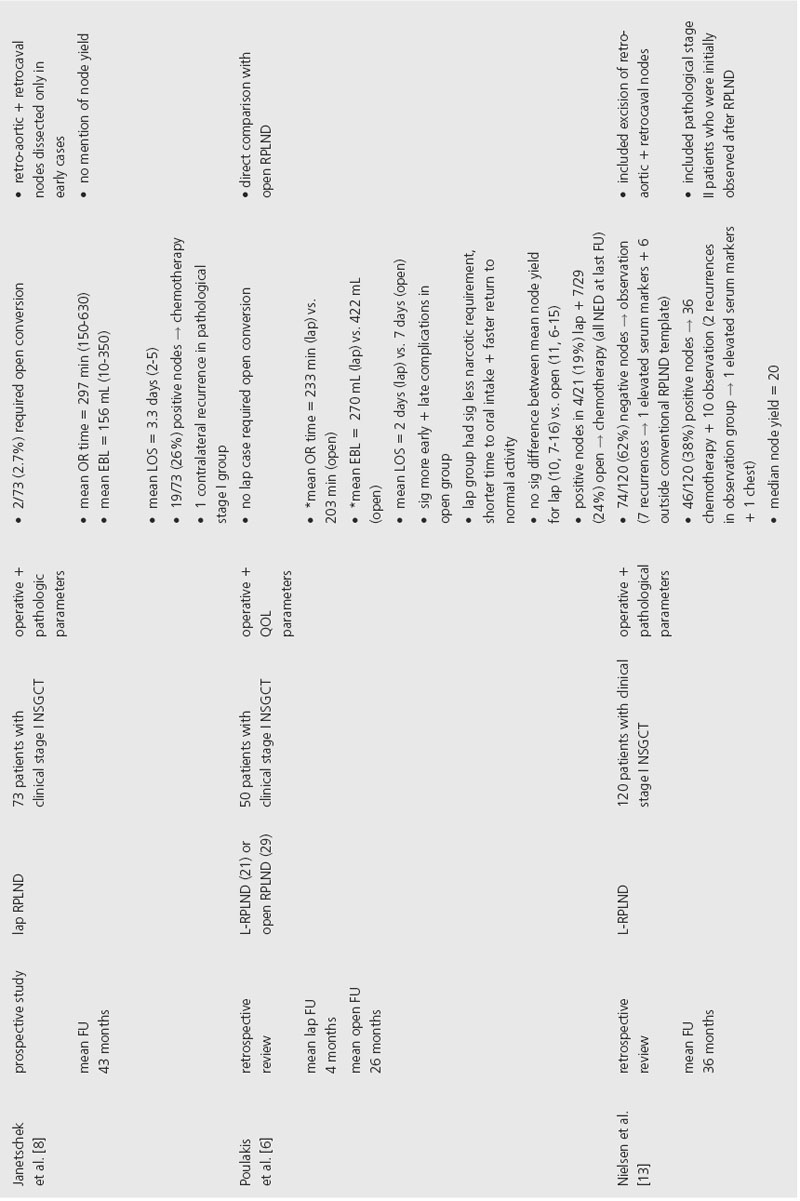

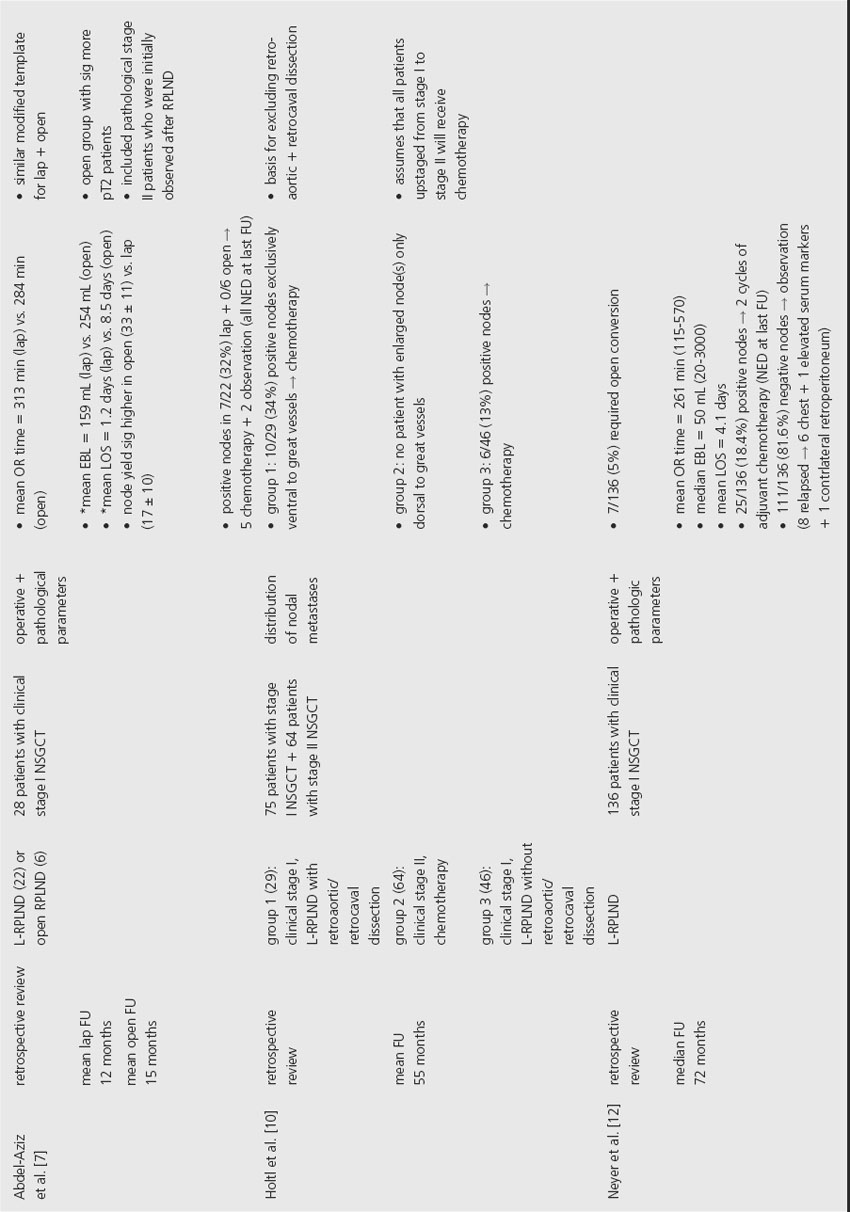

Laparoscopic RPLND (L-RPLND) has been developed since the early 1990s in an effort to reduce perioperative morbidity while maintaining the diagnostic and therapeutic benefits of an open RPLND. The indications for L-RPLND mirror those for a primary open RPLND: stage I or IIA NSGCT, negative serum markers and absence of surgical contraindications. L-RPLND was initially accepted as a diagnostic tool and controversy still surrounds its ability to match the therapeutic benefit of an open RPLND. Multiple reviews published in the last decade have addressed the role of L-RPLND (Table 37.2).

Table 37.2 Role of laparoscopic RPLND

Several series have demonstrated that L-RPLND is associated with less perioperative morbidity. While operative times are typically longer with L-RPLND, studies by Poulakis et al. and Abdel-Aziz et al. reported that L-RPLND resulted in significantly less blood loss and shorter length of hospital stay [6,7]. Poulakis et al. also reported that patients who underwent L-RPLND had significantly less narcotic requirement, shorter time to oral intake and faster return to normal activity when compared to nonrandomized historical controls. In addition, open RPLND was associated with significantly higher rates of early and late postoperative complications. Open conversion was required in 2.7–6.9% of cases, primarily for intraoperative bleeding.

In order to provide comparable therapeutic benefit, L-RPLND should produce similar lymph node yields in comparison to the open technique. This comparison is difficult to assess, however, since many of the studies in the current literature did not perform L-RPLND as a completely therapeutic intervention. While one study noted that L-RPLND “is used for diagnostic purposes only,” another reported that L-RPLND was not completed if grossly positive nodes were encountered during dissection [8,9]. The same study noted that lymph node yield was higher for patients with negative nodes (25 ± 3) compared to patients found to have positive nodes (14 ± 2). Another study that employed a similar template for both L-RPLND and open RPLND reported a significantly higher lymph node yield in the open group (33 ± 11) compared to the L-RPLND group (17 ± 10) [7]. Poulakis et al. reported no significant difference in the lymph node yield between open RPLND (11, range 6–15) and L-RPLND (10, range 7–16), but the lymph node yields reported in this study were considerably lower than other current series so no conclusion can be made based on these data [6].

In order to accurately compare the therapeutic efficacy of open and laparoscopic techniques, series would have to employ similar templates. Even when similar templates were employed, L-RPLND did not uniformly involve dissection of lymph nodes behind the great vessels [7]. The decision to forego dissection behind the great vessels during L-RPLND is based on a study by Holtl et al., which documented the lack of isolated retroaortic or retrocaval lymph nodes [10]. While this study demonstrates that patients will likely be properly staged based on a laparoscopic dissection that does not include lymph nodes behind the great vessels, the authors make the supposition that all pathological stage II patients will receive adjuvant chemotherapy that will theoretically treat any residual retroaortic or retrocaval GCT.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree