While frank esophageal carcinoma rarely presents a diagnostic challenge, early lesions are often tricky to assess. This difficulty stems in part from drawbacks in the classification systems designed to stratify early lesions as a guide for deciding treatment. These systems are complex and wrought with specific pathologic challenges brought on by new treatment modalities. Such interventions as endoscopic mucosal resection, photodynamic therapy, and chemotherapy/radiation combinations present the pathologist with new histologic challenges that have a direct impact on patient care. In this article, we discuss staging issues pertinent to early cancers, histologic sequelae of various treatments, and how these factors affect the pathologist’s role in evaluating esophageal carcinoma.

In 2008, an estimated 16,470 people in the United States were told that they have esophageal carcinoma. During the same year, an estimated 14,280 people died of this disease. This high rate of mortality occurs even though the esophagus is in a relatively accessible location and the use of screening endoscopy is widespread. One reason for the high mortality is the difficulty in properly identifying and treating early lesions. While frank esophageal carcinoma rarely presents a diagnostic challenge, early lesions are often tricky to address. Classification systems designed to stratify early lesions to make treatment decisions are complex and wrought with specific pathologic challenges brought on by new treatment modalities. Such interventions as endoscopic mucosal resection, photodynamic therapy, and chemotherapy/radiation combinations present the pathologist with new histologic challenges that have direct impact on patient care. In this article, we discuss staging issues pertinent to early cancers, histologic sequelae of various treatments, and how these factors affect the pathologist’s role in evaluating esophageal carcinoma.

While the esophagus can harbor a range of neoplasms, two major types of primary esophageal carcinoma comprise the bulk of epithelial lesions in this location: squamous carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Surveillance endoscopy is particularly useful in the evaluation of columnar lesions because it is practical and reliable for identifying and following, via biopsy, Barrett mucosa, a well-established precursor lesion. While patients diagnosed with a deeply invasive carcinoma are usually treated with chemotherapy and radiation followed by surgery, many patients with early lesions are today managed endoscopically. As Heisenberg notes, the act of observation itself changes the entity observed. In the case of esophageal surveillance, the physician does more than just observe; the physician also takes multiple biopsies to evaluate the areas in question. While some changes are seen in Barrett mucosa before medical intervention (eg, duplication of the muscularis mucosae, discussed in the following pages), other changes are created iatrogenically as therapeutic measures or as side effects of these therapeutic measures.

Changes associated with Barrett esophagus: reduplication of the muscularis mucosae and implications for staging

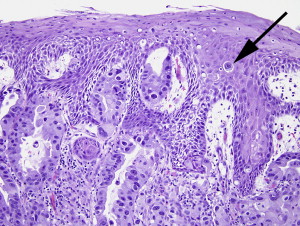

One of the most important recent advances in the evaluation of early esophageal lesions is the recognition and documentation of features of Barrett mucosa beyond the simple presence of intestinal metaplasia. The first mention of such additional features of Barrett mucosa was Rubio and Riddell’s description of the “musculo-fibrous anomaly” in Barrett esophagus. In this and a subsequent study, Rubio and Riddell noted specific changes in the muscularis mucosae, lamina propria, and submucosa, as well as in the epithelium, in association with approximately 81% of Barrett esophagus patients evaluated. These evaluations paved the way for additional observations that led to the description of muscularis mucosae duplication in 1990. In subsequent years, reports were published that substantiated and expanded on these findings. Barrett esophagus came to be recognized as more than just an epithelial lesion; it blossomed into an entity that encompassed the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, and even the submucosa. The feature that arguably creates the most diagnostic difficulty for the pathologist is the formation of multiple muscularis mucosae layers. In areas of intestinal metaplasia, two (or more) layers of muscularis mucosae can be seen. Often these muscular layers are not well delineated, and sparse wisps of muscle are seen between the layers with intermixed loose lamina propria tissue ( Fig. 1 ). The deeper muscularis layer is generally recognized as the original layer, and the superficial layer (the layer closest to the luminal surface) is regarded as the “new” layer. This designation is accepted in part because a direct connection between the deepest layer and the muscularis mucosae in adjacent non-Barrett esophagus can often be identified.

Surprisingly, however, once the phenomenon of muscularis mucosae duplication was recognized and accepted, it was largely ignored in the subsequent literature until recently. Even as investigators fashioned increasingly detailed methods of subclassifying early lesions, muscularis mucosae duplication was not addressed, creating a particularly confounding situation for pathologists facing increasing numbers of endoscopic mucosal resection specimens. Muscularis mucosae duplication and related changes, in addition to intestinal metaplasia, in Barrett esophagus occur in approximately 90% of resection specimens. With such an overwhelming majority of specimens harboring these changes, a clear consensus regarding pathologic staging of adenocarcinomas is essential in the evaluation of specimens for treatment planning and prognostic purposes. Muscularis mucosae duplication remains incompletely understood.

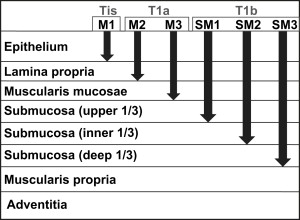

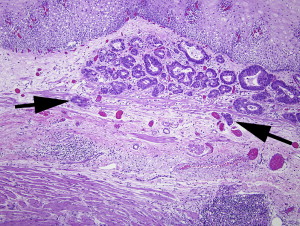

The dilemma for pathologists arises when early adenocarcinoma is detected in a specimen that harbors muscularis mucosae duplication in the setting of Barrett esophagus. The classification of tumor depth for superficial esophageal cancer was first developed for squamous rather than columnar lesions by Japanese colleagues and is described in Fig. 2 . This classification is difficult to apply in the setting of duplicated muscularis mucosae, however. When the carcinoma extends to a portion of the muscularis mucosae or the area between duplicated muscularis mucosae layers, the pathologist must choose to classify the lesion as either an M3 lesion (T1a) or a submucosal lesion (T1b). The dilemma is illustrated in Fig. 3 . That figure shows the carcinoma extending to the area between the two (or more) layers of muscularis mucosae ( arrows ). It remains controversial as to whether this area of lamina propria “between” muscularis mucosae layers is best interpreted as submucosa (since it is beyond some muscularis mucosae), or muscularis mucosae itself (since it has not extended beyond both muscularis mucosae). In interpreting superficial or tangentially embedded samples, the pathologist risks identifying the original (or deepest) layer of muscularis mucosae as muscularis propria, thereby mistaking a T1 lesion for a T2 lesion.

Assigning these criteria is not useful unless there are evidenced-based reasons to choose specific therapy based on the assignments. To this end, Hahn and colleagues evaluated the composition of vascular constituents in both the superficial and deep lamina proprias in 30 patients undergoing esophagogastrectomy, 24 of which had Barrett esophagus. In this series, the density of blood and lymphatic vessels (as identified by CD31 and D2-40 expression, respectively, by immunohistochemistry) did not significantly differ in the submucosal tissue of Barrett esophagus (superficial as well as deep components when duplication occurred) compared with the submucosal tissues of the non-metaplastic squamous esophagus. The investigators concluded that the duplicated (or “new”) muscularis mucosae simply separates the lamina propria into two compartments that do not differ substantially in their vascular constitutents, and should therefore be considered as one lamina propria for purposes of staging, an assertion that remains unvalidated with long-term follow-up studies. It is not yet clear whether or not the “superficial” or “deep” lamina proprias created by the duplicated muscularis mucosae should be considered distinct staging locations under the rubric of intramucosal carcinoma.

Because tumor stage is such an important prognostic indicator, there is great interest in developing a staging system that best represents current knowledge. The current TNM staging system was developed by Pierre Denoix between 1943 and 1952, and has undergone multiple modifications throughout the years to reflect changing knowledge. In a nutshell, the TNM staging system evaluates a particular patient’s disease by assessing the tumor size and spread, the number and location of lymph nodes involved, and the presence and location of metastatic disease. After categories are assigned for T, N, and M, a stage is assigned based on a chart, with stages ranging from stage 0 to stage IVB. Rolling modifications to the TNM system are an expected result of growing medical knowledge. The system has evolved along with medical technology, and has changed over the years to represent a more interdisciplinary approach to disease as opposed to a clinician-centric or pathologist-centric classification system. Before 1987, the classification system had different criteria for pathologic staging of T1 and T2 esophageal lesions, with the clinical definition depending on tumor surface area and the pathologic definition depending on invasion depth. Today, proposals for the modification of the TNM staging system can be submitted to the International Union Against Cancer ( http://www.uicc.org ). Each proposal must include a rationale, analyses of the study, validation of the study, and specific recommendations for classification revision. In the most widely used international staging systems today, lesions invading the lamina and submucosa are both “lumped” as T1, which clearly is misleading for those patients whose lesions are restricted to the lamina propria, as those patients enjoy a better prognosis.

In the past few years, there has been an outcry to further modify the TNM staging system for esophageal carcinoma to better reflect evident patient outcomes. It is widely believed that the sixth edition of the International Union Against Cancer TNM guidelines for staging esophageal carcinoma could usefully be supplemented with additional tumor characteristics to focus on the patients’ prognosis. In 2003, Rice and colleagues evaluated 480 patients who underwent esophagectomy and concluded that the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging of esophageal cancer needed modifications to better reflect patient outcomes. They recommended that T1 be further divided into T1a (intramucosal carcinoma) and T1b (submucosal carcinoma) and that N1 encompass involvement in one or two regional lymph nodes, with N2 defining involvement in three or more regional lymph nodes. In addition, they found that subclassification of M1 was not useful for predicting prognosis.

Wijnihoven and colleagues published an evaluation of a group of 292 patients who underwent esophagectomy in 2007. In this study, the TNM modifications as proposed by Rice in 2003 more accurately predicted patient survival than the International Union Against Cancer TNM classification. Wijnihoven and colleagues also found that the subclassification of M1 into M1a and M1b was not useful for prognosis in their patient cohort. Thompson and colleagues studied 240 patients who underwent resection for esophageal carcinoma. In this study, the addition of a histologic grade and a change in the “pN” portion of the staging system were identified as changes that could improve the prognostic ability of the TNM system.

Changes associated with Barrett esophagus: paget cells associated with Barrett esophagus or with adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction

Paget disease has been described in several locations, including skin of the breast, vulva, perianal region, and axilla. Abraham and colleagues describe Paget cells in squamous esophageal mucosa overlying areas of Barrett esophagus–associated adenocarcinomas in eight patients. The cases with esophageal Paget cells all showed a poorly differentiated tumor component with dyscohesive cell architecture. Interestingly, Abraham and colleagues note that the Pagetoid component of most of the cases in their study were identified only on retrospective case review. A prevalence of 4.9% was calculated based on their study material, which included 103 esophageal adenocarcinomas without Paget cells. Anecdotally, we too have only observed this phenomenon in the esophagus in association with invasive carcinoma, as described by Abraham and colleagues ( Fig. 4 ), in contrast to this appearance in the breast or perineum, where the lesion can truly be an early lesion akin to a skin appendage neoplasm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree