Successful treatment of unresectable and metastatic gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) requires the thoughtful choice of systemic therapy as a component of a multidisciplinary therapeutic approach. The role of somatostatin analogues is established in symptom relief, but the efficacy of interferon and radiopeptide targeted therapy is not clear. The utility of a variety of tyrosine kinase and antiangiogenic agents is variable and under investigation, whereas the role of cytotoxic chemotherapy in poorly differentiated GEP-NETs is accepted. Overall, the ideal treatment of more indolent tumors is less certain. Reassessments of the GEP-NET pathology classification has provided improved logic for the role of a variety of agents, whereas the precise positioning of many new agents that target molecular pathways of angiogenesis and proliferation is under examination. This article describes the current options for systemic therapy for GEP-NETs within the framework of the current World Health Organization classification system.

Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) are more common than previously thought and second only to colorectal cancers as the most prevalent gastrointestinal cancers. Systemic therapy for GEP-NETs is indicated to control symptoms of bioactive peptide and amine hypersecretion and to reduce tumor proliferation in the setting of unresectable or recurrent disease. Although the treatment of individual tumors is often complex and requires multidisciplinary expertise, there are stable themes that guide the choice of systemic treatment of GEP-NETs. These themes are well described in recent consensus statements such as the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS), the UK and Ireland Neuroendocrine Tumor Network, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and the European Society of Medical Oncology. Broadly speaking, all systemic treatment is palliative: somatostatin (SST) analogues effectively reduce symptoms of neuroendocrine hypersecretion (eg, carcinoid syndrome), systemic treatment does not markedly change the natural history of well-differentiated tumors, cytotoxic chemotherapy is indicated for poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas, and systemic therapy should be 1 part of a multimodal intervention that considers surgery, local therapies, and peptide receptor radiolabeled therapy. This article describes recent developments in systemic pharmacotherapy, particularly in the more controversial indolent tumors, with a focus on novel treatments that target specific proteins in cellular proliferation pathways. The lack of globally accepted definitions of what precisely represents a particular grade or stage of tumor has hampered both delineation of treatment strategy and assessment of efficacy and outcome with different treatment regimens.

Classification

The terms used to describe neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are bewildering in their diversity. NET nomenclature has been difficult, because Obendorfer named the tumor as “karzinoide” or cancer-like before later observing that these tumors were truly malignant. A simplistic classification based on embryologic origin, which classified carcinoids as of fore-, mid-, or hindgut origin, emerged in the 1960s and is still used in some areas. In the current decade, 2 new classifications have emerged, although neither has gained universal acceptance. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification describes tumors by their degree of differentiation and site of origin, and the more recent ENETS classification includes TNM-type staging, augmented by the Ki-67 index of proliferation. However, controversy remains on whether Ki-67 or the precise number (of positive cells) that represents a clinically or therapeutically relevant cipher should be assessed. The changing classification and the natural reluctance of most clinicians to abandon terms associated with a known therapeutic approach have resulted in a variety of names remaining in the pathologist and clinician lexicon. For example, the term neuroendocrine tumor is often used to describe the entire family of tumors, but is now a histologic stage in the WHO classification, in which it describes the well-differentiated and more indolent end of the GEP-NET spectrum. Similarly, the term carcinoid is used interchangeably by clinicians to describe all NETs, only NETs with indolent biologic behavior, or only NETs originating in the small bowel. However, in the WHO classification, carcinoid is now synonymous with NET, and either term describes grade 1 tumors ( Table 1 ). However, it is generally agreed that the term carcinoid should be phased out because it denotes an archaic concept that is no longer compatible with the modern biologic understanding of neuroendocrine malignancy.

| WHO Classification | WHO Synonym | Biologic Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor | Carcinoid | Uncertain malignant potential |

| Well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma | Malignant carcinoid | Low-grade malignancy |

| Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma | High-grade malignancy |

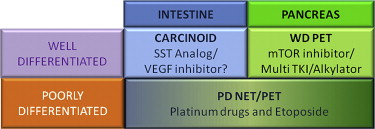

In this article, the authors group GEP-NETs along the lines of the WHO definition, but they have made slight adjustments to approximate the inclusion criteria of pharmacotherapeutic trials and to separate GEP-NETs by the appropriate therapeutic approaches. This should not imply that the authors believe that this grouping has any inherent value for future classification but simply that it provides a more easily comprehensible system by which the logic of therapeutic strategies can be appreciated. Therefore, the authors combine the WHO grade 1 and 2 tumors and divide them by the site of tumor origin as either well-differentiated carcinoids (ie, of enterochromaffin cell origin) or well-differentiated pancreatic NETs ( Fig. 1 ). The group of poorly differentiated tumors (including WHO grade 3) irrespective of the site of origin is discussed separately.

Impediments to the development of new pharmacologic therapy for GEP-NETs

Although some consensus has emerged on the choice of systemic treatment, the trial literature used to make these decisions is problematic. The incidence of each subtype of GEP-NET is low, and there is broad variability in the biologic behavior within each subtype. The lack of a widely accepted classification and staging system hinders recruitment of homogenous trial participants. Single centers lack sufficient cases of GEP-NET subtypes for adequate recruitment. As a result, most studies are retrospective, include heterogeneous tumor types, often lack standardized entry criteria, reflect single-center experience, and are underpowered. Most trials are uncontrolled, and the few controlled trials do not compare the intervention with best supportive care. Furthermore, most studies are funded by pharmaceutical companies with the unavoidable implications inherent therein. Finally, the more indolent GEP-NETs are difficult to assess using traditional measures of efficacy in trial design. The traditional gold standard for therapeutic efficacy in a nonrandomized trial is the objective response rate, but this measure has uncertain utility when the tumor is slow growing and the action of the therapeutic agent is cytostatic. Nonetheless, this compromised dataset has been used to draw the conclusions that follow, based on the somewhat flawed assertion of “it’s the best we have.”

Impediments to the development of new pharmacologic therapy for GEP-NETs

Although some consensus has emerged on the choice of systemic treatment, the trial literature used to make these decisions is problematic. The incidence of each subtype of GEP-NET is low, and there is broad variability in the biologic behavior within each subtype. The lack of a widely accepted classification and staging system hinders recruitment of homogenous trial participants. Single centers lack sufficient cases of GEP-NET subtypes for adequate recruitment. As a result, most studies are retrospective, include heterogeneous tumor types, often lack standardized entry criteria, reflect single-center experience, and are underpowered. Most trials are uncontrolled, and the few controlled trials do not compare the intervention with best supportive care. Furthermore, most studies are funded by pharmaceutical companies with the unavoidable implications inherent therein. Finally, the more indolent GEP-NETs are difficult to assess using traditional measures of efficacy in trial design. The traditional gold standard for therapeutic efficacy in a nonrandomized trial is the objective response rate, but this measure has uncertain utility when the tumor is slow growing and the action of the therapeutic agent is cytostatic. Nonetheless, this compromised dataset has been used to draw the conclusions that follow, based on the somewhat flawed assertion of “it’s the best we have.”

Well-differentiated (low-grade) carcinoid tumors

Only a few carcinoid tumors are completely resectable, meaning that most carcinoid tumors would benefit from systemic antiproliferative therapy if an effective option existed. Disease symptoms related to the secretion of bioactive peptides and amines were a dominant event in the past, when a far greater percentage of advanced NETs were undetected. Now, only approximately 10% to 20% of carcinoid tumors produce the flushing, diarrhea, bronchospasm, and cardiac fibrosis (previously referred to as the carcinoid syndrome). This group benefits from agents that control hypersecretion, namely, the SST analogue class of drugs, or more specific agents that actually interfere with serotonin secretion.

SST Analogues

SST analogues such as octreotide and lanreotide effectively control symptoms of carcinoid syndrome in most cases in which the underlying tumor has a low proliferative index, although in some patients the effect tends to wane over time. This effect reflects either an increase in tumor growth or tachyphylaxis and can be temporarily overcome by incremental dose increases of the SST analogue or the addition of interferon. Long acting octreotide (intramuscular formulation), for example, has been used at more than the usual dose range (20–30 mg monthly) without additional toxicity.

SST analogues may also have an antiproliferative effect on GEP-NETs. Endogenous SST has a well-documented inhibitory effect on gastrointestinal cell physiology and an antiproliferative effect on type II and III gastric carcinoids. The PROMID study randomized 85 patients with well-differentiated midgut NETs to receive long acting octreotide (intramuscular formulation) or placebo. Almost all patients (95%) had tumors with a Ki-67 of less than 2% positive cells, and 39% of patients had symptoms of the carcinoid syndrome. The time to progression (TTP) was 6 months in the placebo group compared with 14 months in the group given octreotide LAR. This effect was most marked in the subgroup with low-volume liver metastases (<10% of liver volume), in which TTP was 29 months. This study has been criticized because despite multicenter participation, it was slow to recruit (8 years), had a small sample size, and the intervention and placebo groups were not identical. The intervention group had a significantly longer period between diagnosis and commencing octreotide, raising a concern that the group that received octreotide included more indolent tumors. Furthermore, there was no difference in median overall survival, although all patients in the placebo group were allowed to cross over to octreotide LAR at progression. This study exemplifies the difficulty in conducting NET research, and the authors are left with an appealing but uncertain conclusion that has excited much debate. Although some groups have adopted the PROMID data as providing the basis for a paradigm shift in therapeutic strategy (all NETs should be treated with an effective antiproliferative therapy), significant reservations have been expressed and it seems likely that more data (especially survival improvement) to validate SST as an antiproliferative agent are required before the matter is satisfactorily resolved.

The promising novel SST analogue pasireotide, a pan-receptor SST agonist, has been proposed as possessing the biologic credentials to outperform octreotide and lanreotide. There are 5 types of SST receptors (SSTRs). Pasireotide has a far higher affinity for SSTRs 1, 3, and 5 than octreotide or lanreotide. This broader specificity has been touted to likely provide an antiproliferative advantage. For example, the stimulation of SSTR1 is associated with reduced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptor (VEGFR) 2 expression, which may prevent tumor growth by reducing effective blood supply to the tumor. Also, receptor subtypes vary between and within tumor types, so a broad receptor subtype affinity might be an advantage. Pasireotide reduced the symptoms of hypersecretion in 27% of patients with carcinoid syndrome resistant to octreotide and inhibited growth in carcinoid cell lines in vitro. To date, no convincing data have been presented to indicate a major advantage for this pan-receptor agonist, and evidence of significant, unresolved issues relating to pasireotide-induced abnormalities in glucose metabolism continues to dominate clinical concerns.

Therapy Targeting Cellular Pathways of Proliferation

NETs exhibit some differences in molecular profile to most other tumors. In contrast to many adenocarcinomas, they seldom express microsatellite instability and mutations in the Ras/Raf/MAP kinase or the transforming growth factor β pathway. Molecular profiling of tumors instead shows overexpression of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K-Akt-mTOR) pathway and the insulinlike growth factor 1 receptor. Administering a pharmacologic agent that inhibits one or more of these proproliferative proteins provides a rationale for patient- or tumor-specific therapy and has been tested in early-stage clinical trials.

The most successful therapeutic agents for well-differentiated carcinoid tumors have targeted tumor angiogenesis. VEGF and VEGFR seem to be excellent targets based on clinical phenotype and cell line data. Carcinoid tumors are macroscopically vascular as evidenced by enhancement in the arterial phase of computed tomographic scanning, a characteristic often used to diagnose GEP-NETs radiologically. Carcinoid tumors express high levels of VEGF, elevated expression of VEGF correlates with increased angiogenesis and decreased progression-free survival (PFS) among patients with low-grade NETs. Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to VEGF and prevents activation of the VEGFR ( Fig. 2 ). Bevacizumab has been evaluated in a phase 2 trial of 44 patients with unresectable or metastatic carcinoid tumors on a stable dose of SST analogue. Patients were randomized to 18 weeks of bevacizumab or pegylated interferon alfa-2b therapy before going on to receive both drugs. The group administered bevucizumab achieved radiologic reduction in tumor vascularity, tumor shrinkage in 18%, and a better 18-week PFS of 95% as compared with 67% in the pegylated interferon alfa-2b group. Because of planned crossover at 18 weeks, no viable overall survival data were generated. Despite the small numbers, this promising finding warrants further investigation.

Two other tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (sorafenib and sunitinib) have anti-VEGF or anti-VEGFR properties as part of their targeting arsenal; however, they exhibit only modest in vivo activity in carcinoid tumors. The oral multi-TKI sorafenib inhibits VEGFRs 2 and 3, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) β, RAF, FLT-3, and c-kit. Of 41 patients with carcinoid tumor, 4 had a radiologic response based on the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) and 3 had a smaller non-RECIST response. Of concern is that approximately 40% of patients experienced grade 3 toxicity. Sunitinib is an oral multi-TKI that targets VEGFRs 1, 2, and 3; PDGFR α and β; stem cell factor receptor; glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor receptor; and FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT-3). Forty-one patients with well-differentiated metastatic carcinoid tumor received sunitinib as part of a nonrandomized phase 2 study. Only 1 of 41 patients achieved a radiologic response, so further accrual was abandoned. Tumor differentiation in the participants is not described, although small cell carcinoma was excluded. Sunitinib caused significant adverse events, with more than 50% of patients needing a dose reduction or treatment delay.

Vatalanib, an oral TKI that targets multiple VEGFRs and PDGFRs, did not achieve any radiologic response in 2 small studies, and the drug was moderately toxic. Given the failure of the VEGFR inhibitors sunitinib and vatalanib and the relative success of bevacizumab and sorafenib, it seems likely that targeting VEGF is more effective than targeting its receptor, VEGFR, in well-differentiated carcinoid tumors.

Two other drugs with antiangiogenic properties have had a minimal effect on carcinoid tumors. Thalidomide has an antiangiogenic and immune-modulating effect by inhibiting tumor necrosis factor α. No radiologic responses were seen in 18 patients with carcinoid, and grade 3 toxicities were common, with 4 patients stopping treatment because of the toxicity. Endostatin is an endogenous inhibitor of vascular endothelial migration and proliferation. No patients (0/40) achieved a measurable tumor response when given a recombinant version of endostatin. The experience with these 5 drugs represents the practical clinical difficulties encountered when seeking to inhibit a rational biochemical selected target.

Although the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway is upregulated in carcinoid cell lines and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors reduce proliferation of cell lines, the in vivo response has been disappointing. The intravenous mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus achieved only 5% radiologic response rate in progressive carcinoid tumors in a small phase 2 trial. Similarly, experience with the small molecule endothelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) TKI, gefitinib, is an example of thwarted rational target choice. EGFR is overexpressed in NETs, and EGFR inhibitors reduce growth in carcinoid cell lines. A phase 2 study of gefitinib, including 57 patients with carcinoid tumors, reported that only 1 of 40 evaluable patients achieved a radiologic response, although 32% had a longer period of stability (TTP) than they had experienced before study entry (determined if TTP on study was 4 months longer than TTP before study). This overall poor response might reflect the observation that NETs lack either of the 2 facilitating EGFR tyrosine kinase mutations associated with gefitinib activity in non–small cell lung cancer. Therefore, although EGFR remains a rational target, the current agents might not be able to adequately inhibit the receptor.

Other targeted agents have been disappointing. A trial of the c-kit and PDGFR inhibitor imatinib showed minimal activity in a group of patients with endocrine tumors, including 2 patients with carcinoid and 1 with a pancreatic NET. There were no objective responses in these 3 patients.

Cytotoxic Chemotherapy

A maxim of the medical oncologist is that slow-growing tumors seldom respond to traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy. The clinical determination of slow growth can be quantified using indices of proliferation, such as the number of mitoses per high-power field or the percentage of cells expressing Ki-67. Higher indices of proliferation (Ki-67>20%) are associated with significant but short-lived responses to chemotherapy, whereas very low indices of proliferation (Ki-67<2%) tend to infer resistance to cytotoxic chemotherapy. It is now accepted that there is virtually no role for cytotoxics in well-differentiated carcinoid tumors, and response rates are less than 15%. Similarly, adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of liver metastases does not reduce the rate of relapse. Former enthusiasm for agents such as streptozotocin, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide has abated given their toxicity and limited efficacy. The real advance in cytotoxic chemotherapy is the realization that it has no role in carcinoid tumors with low indices of proliferation. Cytotoxic chemotherapy takes primacy in the aggressive, poorly differentiated carcinoid tumors and is described later.

Summary

Overall, therapy targeting cellular pathways of proliferation has been ineffective for most patients with well-differentiated carcinoid tumors. Radiologic responses were seen in only 2% to 18% of patients in each series. There might be a role in well-differentiated carcinoid tumors for agents that target VEGF directly. Although response rates were low, most drugs had activity in some tumors. The real challenge is to identify and predict which tumors will respond to a specific therapy. For example, although treatment with VEGF inhibitors was successful in a few patients, it is well recognized that the level of VEGF expression is highly variable among different carcinoid tumors. Delineation of specific levels would identify patients likely to be responsive to VEGF inhibition. Similarly, expressions of VEGF and VEGFR are lower in liver metastases than in the primary tumor, suggesting that VEGFR inhibition might be a better strategy when disease is unresectable but not yet metastatic. And finally, if a cytostatic response is achieved in uncontrolled phase 2 trials, the activity of such agents may be undetected by measuring the response rate, unless a randomized controlled trial is undertaken.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree