(1)

Department of Endoscopy, Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital, Fukuoka, Chikushino, Japan

14.1 Overview

14.6 The Role of Magnifying Endoscopy in the Early Gastric Cancer Delineation, and Clinical Strategies

Abstract

The clinical uses of ME, as outlined in the chapter on M-WLI, are:

Keywords

Clinical applicationDelineationEarly gastric cancerMagnifying endoscopyNarrow-band imaging14.1 Overview

14.1.1 Clinical Usefulness of M-NBI

The clinical uses of ME, as outlined in the chapter on M-WLI, are:

1.

Differential diagnosis between gastritis and gastric cancer in reddened flat or depressed lesions

2.

Preoperative diagnosis of early gastric cancer

14.1.2 Detection of IIb Type Tumors and Microcarcinomas

These are not separate clinical applications but rather strategies for the detection of IIb type tumors and microcarcinomas in clinical situations. In this chapter, I will omit the detailed explanations of image interpretation and notations of the ME findings as in the previous chapter. Instead I will present some typical cases in which we use the VS classification to distinguish between cancer and noncancer, focusing on the clinical usefulness of M-NBI.

14.1.3 Clinical Usefulness, Limitations and Clinical Strategies According to the Degree of Difficulty Category (Table 14.1)

Table 14.1

Degree of difficulty categories for delineation of tumor margins using ME

Cases where equivalent results are obtained with magnifying and conventional endoscopy | |

Category 1 | Cases where the entire tumor margin can be delineated by conventional endoscopy alone |

Cases where magnifying endoscopy is superior | |

Category 2 | Cases where part of the tumor margin is indistinct using conventional endoscopy alone, but the entire margin can be delineated using magnifying endoscopy |

Category 3 | Cases where the entire tumor margin is indistinct using conventional endoscopy alone (0 IIb) |

Cases where the presence of a tumor is uncertain using conventional endoscopy, but the presence of a lesion is confirmed, and the margins delineated, using magnifying endoscopy | |

Category 4.1 | Cases where the margins were thought to be clearly delineated using conventional endoscopy, but the presence of an adjacent IIb lesion is confirmed using magnifying endoscopy |

Category 4.2 | Cases where an accessory lesion is detected in the vicinity of the main lesion |

Category 4.3 | Cases where the presence of a tumor is uncertain, let alone its margins, using conventional endoscopy |

Limitations of magnifying endoscopy | |

Category 5.1 | Cases where the presence of a tumor is uncertain using conventional endoscopy, but the presence of a lesion is confirmed, and a differential diagnosis can be made, but the margins cannot be delineated, using magnifying endoscopy |

Category 5.2 | Cases where the presence of a tumor can be detected using conventional endoscopy, but a differential diagnosis cannot be made and the margins cannot be delineated using either conventional or magnifying endoscopy (undifferentiated cancer) |

In this chapter, I have classified the situations we face clinically into categories according to the degree of difficulty of diagnosis using conventional endoscopy. For lesion detection, differential diagnosis between cancerous and non cancerous lesions, and delineation of tumor margins, I have noted separately for conventional endoscopy (dye spraying method) and ME, possible (○), limited (Δ), or impossible (×). I will discuss the advantages and limitations of each method, particularly with regard to their clinical application in preoperative diagnosis and pre-ESD marking. Finally, I will outline the clinical strategies I have developed, and summarize my thoughts regarding the applications of conventional endoscopy and ME. I have included these clinical strategies in the relevant section on each category.

14.1.4 Clinical Strategies

Commencing with the conclusions, the applications for preoperative zoom gastroscopy and the strategies that we will derive from this chapter are as follows: All differentiated-type early gastric cancers and, in particular, differentiated-type cancers whose margins cannot be delineated using conventional endoscopy, or occult cancers that cannot be detected using conventional endoscopy, are good applications.

On the other hand, ME is not indicated in cases of undifferentiated-type carcinoma, and in particular delineation of tumor margins should be performed by taking at least four biopsies of the surrounding mucosa.

14.2 Preoperative Delineation of Tumor Margins Using the Degree of Difficulty Categories for Delineating the Tumor Margins

14.2.1 Fundamentals of Preoperative Delineation of Tumor Margins

M-WLI and indigo carmine dye spraying is the standard method of preoperative delineation of tumor margins.

The process of endoscopic diagnosis can be broadly divided into lesion detection, differential diagnosis, and preoperative diagnosis (histological type, depth of invasion, margins, presence of ulceration, and size). At my hospital, the initial preoperative investigations for cases of gastric cancer are conventional endoscopy using the indigo carmine dye spraying method. Based on the depth of invasion, extent of lateral spread, and biopsy findings, we make a detailed diagnosis of the histological degree of differentiation and decide whether endoscopic or open surgical treatment is indicated. For cases of differentiated-type cancer, where endoscopic surgical treatment is indicated, if the tumor margins are unclear, in part or entirely, we conduct a detailed examination using ME with WLI and/or NBI to delineate the tumor margins.

For tumors whose margins, in part or entirely, can only be delineated using ME, we place markings using ME prior to endoscopic treatment.

For tumors whose margins cannot be delineated over their full circumference even using ME, we either take biopsies, or if the margin cannot be identified in only a small segment, mark the mucosa slightly further from the lesion, where it shows a regular MV and/or MS pattern.

In the background of cases requiring the abovementioned techniques, it is worthy of note that early gastric cancer with unclear margins, not showing a typical macroscopic appearance, is on the rise [2, 3], and advances in treatment methods have made it necessary to accurately delineate tumor margins over their full circumference [2, 3].

14.2.2 Additive Effect of Magnifying vs Conventional Endoscopy, and Limitations

As a quick summary of the additive effect of magnifying vs conventional endoscopy, ME has made it possible to delineate the margins of IIb and IIb-like lesions, and detect IIb accessory cancers and microcancers, that were not possible with conventional endoscopy. However, every useful new diagnostic technique must also have some limitations. What is extremely important is what are the characteristics of the cases where ME is of limited usefulness, and how we should deal with such cases.

Accordingly, in this chapter I will discuss the advantages and limitations of ME in a variety of clinical situations, beginning with preoperative delineation of cancer margins and clinical strategies for these cases where ME is of limited usefulness.

In a study conducted at my hospital [4], out of 350 patients who underwent ESD, the margins were unclear using conventional endoscopy in 67 lesions (19 %). We can anticipate an additive effect in cases such as these.

Of the 67 lesions with unclear margins using conventional endoscopy, we examined 58 using ME. Of these, we were able to delineate the entire margin, which had been unclear using conventional endoscopy, using ME in 45 lesions (possible lesions) (78 %). The margin could not be identified in only a small segment using ME (limited lesions) in ten lesions (17 %), and the margin could not be identified at all even with ME (impossible lesion) in three lesions (5 %). In other words, if we add together the possible and limited lesions, the additive effect for ME in lesions with unclear margins using conventional endoscopy was 95 %.

Of the ten limited lesions for ME, macroscopically widespread lesions with IIb-like margins, or with accessory IIb type lesions, were common. The breakdown of the histological characteristics of the unclear marginal segments using ME was as follows: (1) Seven lesions were extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinomas (cancers with low-grade atypia) with a surface replacing growth pattern, (2) Two lesions were in part undifferentiated-type carcinoma, and (3) One lesion was a moderately differentiated-type adenocarcinoma. Of the three impossible lesions, two were undifferentiated-type carcinomas, and one lesion had the histological findings of an extremely well-differentiated adenocarcinoma 2 mm in diameter.

We can therefore see that, even using the latest magnifying endoscope with NBI, there are limitations in delineating the margins of undifferentiated-type carcinomas. For margin delineation in suspected undifferentiated-type carcinomas, we should preoperatively take multiple biopsies, e.g., the 4 point biopsy method, and histologically confirm the absence of cancer in all biopsy specimens. Even in cases scheduled for open surgery, it is mandatory to take multiple biopsies from the oral side of the proposed line of resection and confirm that there is no cancer invading the surgical margin.

14.3 Cases Where Equivalent Results Are Obtained with Magnifying and Conventional Endoscopy

14.3.1 Category 1

Cases where the entire tumor margin can be delineated by conventional endoscopy alone (Table 14.2 and Figs. 14.1 and 14.2).

Table 14.2

Margin delineation: delineable using conventional endoscopy, delineable using magnifying endoscopy (Category 1)

Detect lesion | Characterize | Delineate margins | |

|---|---|---|---|

Conventional endoscopy/dye spraying | ○ | ○ | ○ |

Magnifying endoscopy | ○ | ○ | ○ |

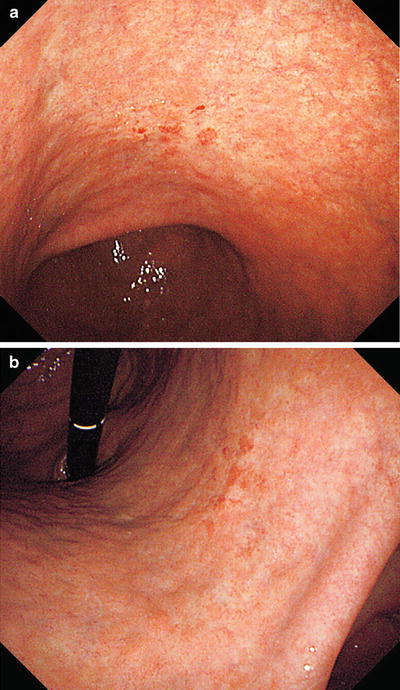

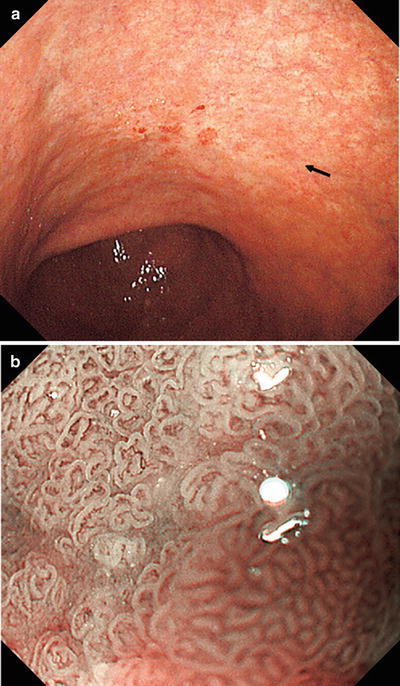

Fig. 14.1

Cases where the entire tumor margin can be delineated using conventional endoscopy alone

Fig. 14.2

Clinical strategy: marking using conventional endoscopy

As this category refers to existing conventional endoscopic techniques, I have not included any case studies.

14.4 Cases Where Magnifying Endoscopy is Superior

14.4.1 Category 2

Cases where part of the tumor margin is indistinct using conventional endoscopy alone, but the entire margin can be delineated using magnifying endoscopy (Table 14.3 and Figs. 14.3–14.11).

Table 14.3

Margin delineation: limited using conventional endoscopy, delineable using magnifying endoscopy (Category 2)

Detect lesion | Characterize | Delineate margins | |

|---|---|---|---|

Conventional endoscopy/dye spraying | ○ | ○ | Δ |

Magnifying endoscopy | ○ | ○ | ○ |

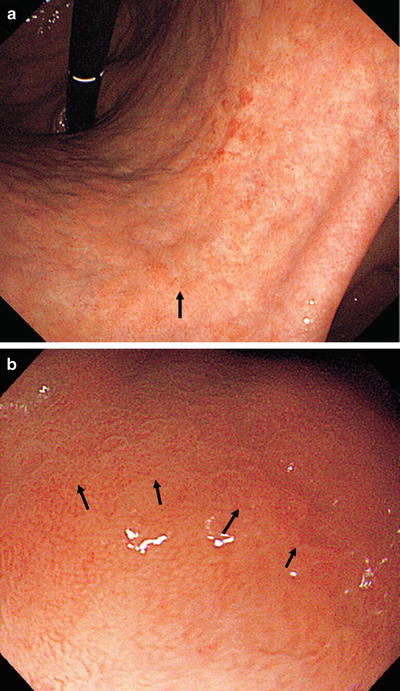

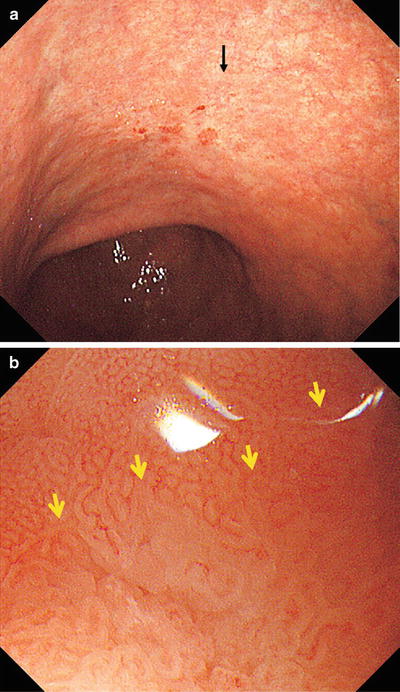

Fig. 14.3

Cases where the tumor margin is unclear in part using conventional endoscopy alone, but the margin can be delineated in its entirety using magnifying endoscopy

Fig. 14.4

Clinical strategy: marking using magnifying endoscopy of only the part of the margin that was unclear using conventional endoscopy

Fig. 14.5

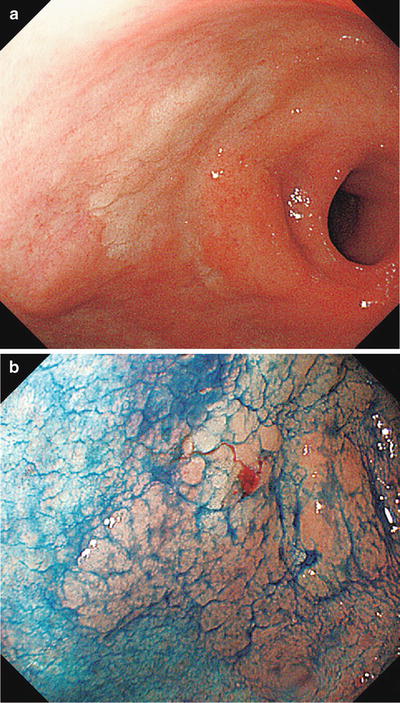

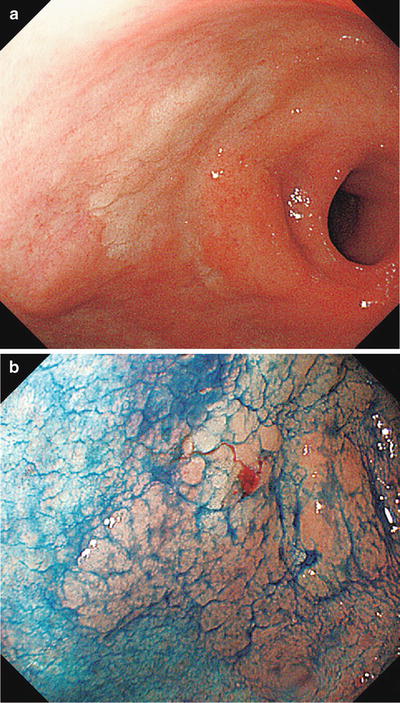

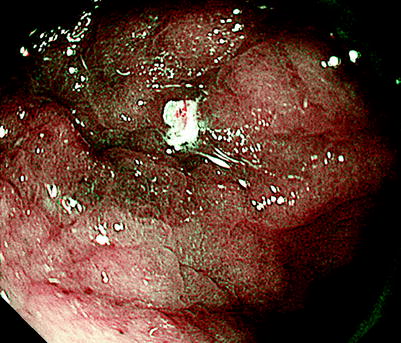

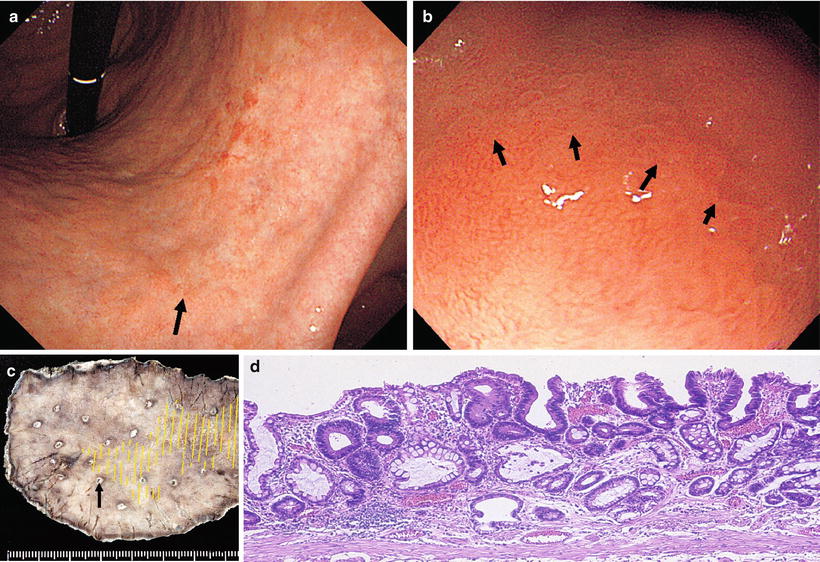

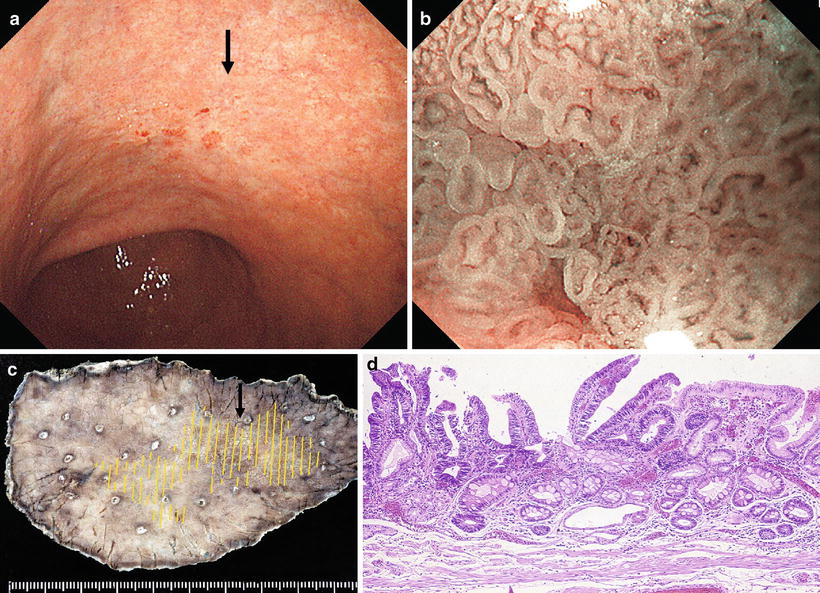

(a–d) Non-magnifying endoscopic findings (GF-240). (a) Detailed examination using a side-viewing scope revealed a red to pale IIa type aggregating superficial elevated lesion on the anterior wall of the gastric antrum (extensive IIa type aggregating superficial elevated lesions require particular caution, as they often contain areas resembling IIb type, or are associated with accessory IIb lesions). (b) Dye spraying reveals a surface structure with granules of different sizes. The oral and greater curvature margin corresponds to the elevated area. (c, d) At the lesser curvature and anal margin, the granular projections gradually become indistinct, and the differences in coloration and elevation between the lesion and the background mucosa become unclear (IIb type area). Here we are unable to accurately delineate the margins, a requirement for ESD

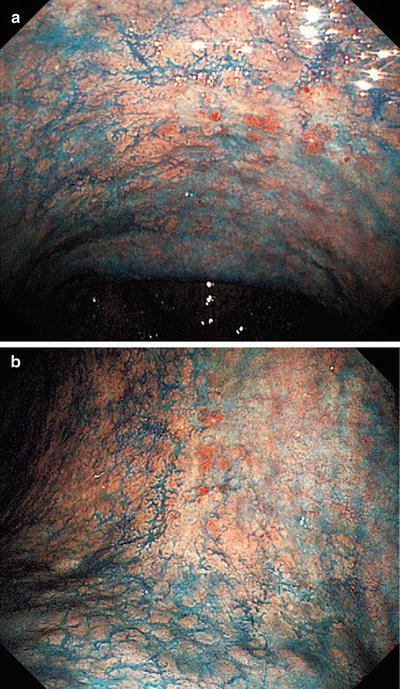

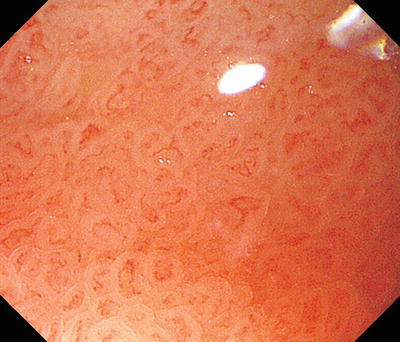

Fig. 14.6

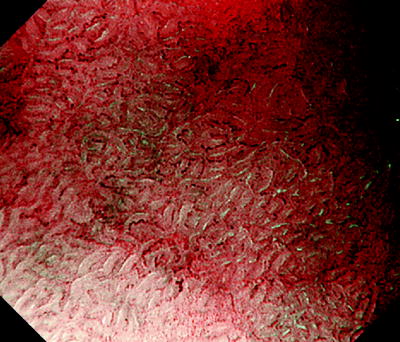

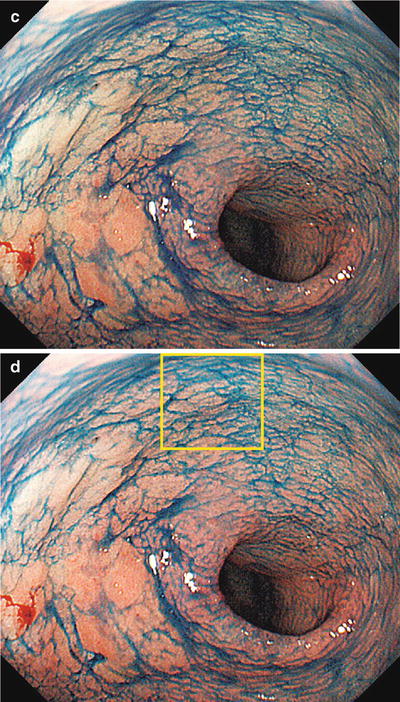

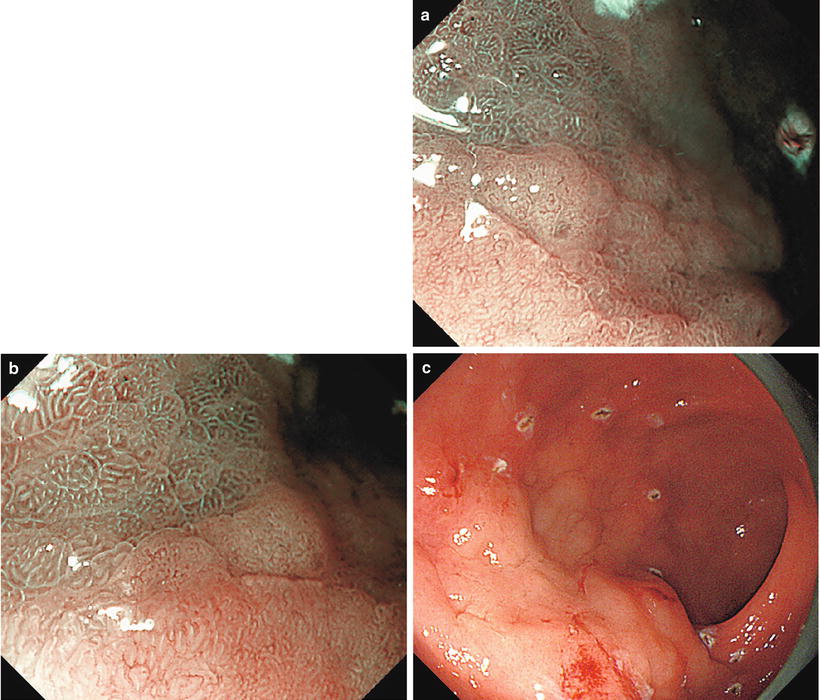

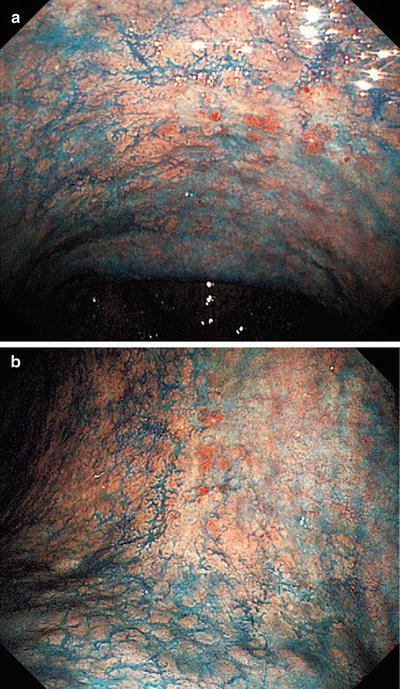

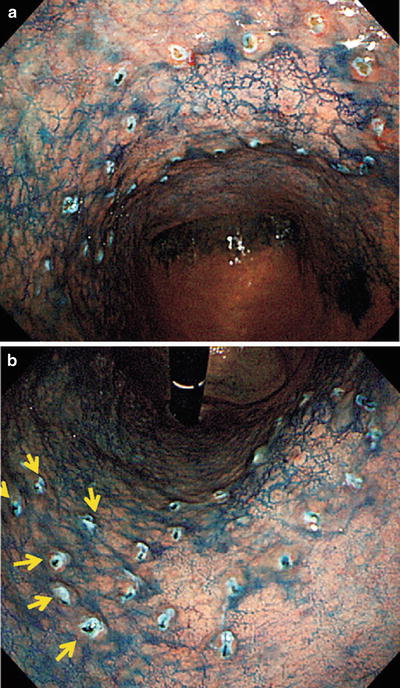

Here we reexamine using M-NBI the lesser curvature and anal margin of the area enclosed by a rectangle in Fig. 14.5d We can clearly see a typical regular MV pattern plus regular MS pattern (LBC+) in the noncancerous background mucosa. Accordingly, this is noncancerous mucosa with intestinal metaplasia

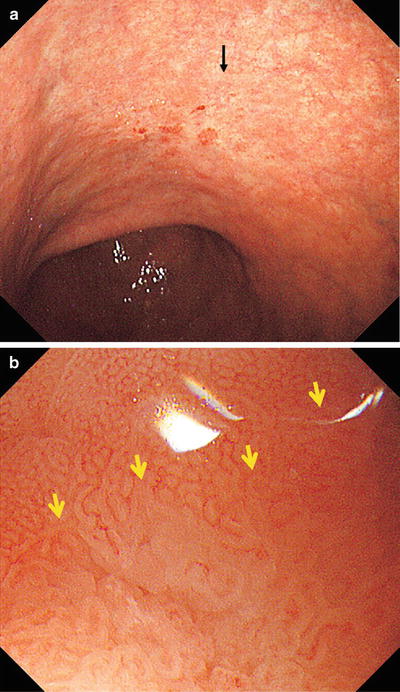

Fig. 14.7

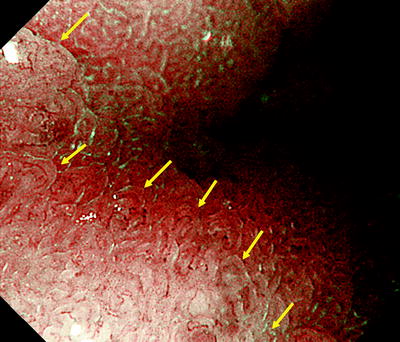

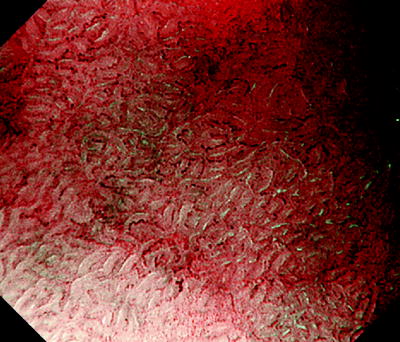

With reference to the abovementioned ME findings of background mucosa, moving from the surrounding background mucosa towards the lesion using ME we see a clear demarcation line (DL) where the regular MV pattern plus regular MS pattern is lost. Within the lesion we can identify an irregular MV pattern plus irregular MS pattern, and we have delineated a typical cancer margin.

Fig. 14.8

Under ME, we placed markings outside the DL in this area

Fig. 14.9

(a–c) We can easily determine the other sections of the lesser curvature margin using M-NBI (low magnification) and the remaining sections of the margin using conventional endoscopy. In the end, the lesion margin could be delineated over its entire circumference, and markings were placed several mm outside the DL. At ESD, the entire lesion was resected in one piece, including the markings

Fig. 14.10

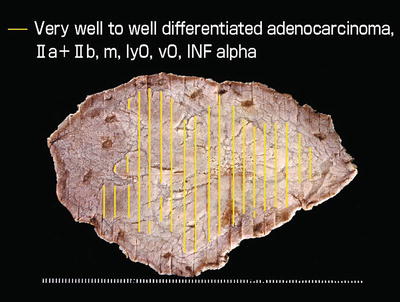

Endoscopically resected specimen fixed in formalin, macroscopic findings and reconstruction of lesion. The resected specimen is 97 mm × 64 mm in size, and the cancer 57 mm × 48 mm. The preoperative markings are clearly identifiable, and we can confirm that the markings were accurately placed

Fig. 14.11

(a–c) Comparison of endoscopic findings, resected specimen and histological image. b shows the reconstructed resected specimen rotated so the markings correspond to those in a for comparison. c shows the pathohistological findings of the marginal area indicated by the letter d. No difference in height is seen between the cancerous and noncancerous areas. The noncancerous background mucosa shows complete type intestinal metaplasia, with no gastric proper glands. In other words, these are the findings of metaplastic atrophic gastritis. The cancerous mucosa shows atypical glands thinly replacing the surface of the noncancerous glands

Anterior wall to lesser curvature of the gastric antrum, 0 IIa type, 55 mm × 48 mm in size, well to very well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, depth of invasion M (Figs. 14.5a,14.6, 14.10 and 14.11a and part of this case study reprinted with modifications from [1] by permission of Stomach Intestine Tokyo; Figs. 14.5a–14.11c).

14.4.1.1 Discussion

When we consider how these tissue structures give rise to the above endoscopic findings, the reasons we cannot discern the differences between cancerous and noncancerous mucosa using conventional endoscopy alone are as follows: The noncancerous background mucosa has a low vascular density due to intestinal metaplasia associated with atrophic gastritis and the tumor has also arisen and grown replacing the surface layers of the atrophic mucosa, so the vascular density in the tumor itself is also low, as is the degree of irregularity of the tumor vessels. However, with M-NBI we can obtain clear images of the regular MV pattern plus regular MS pattern, with the assistance of the presence of LBC, in the background mucosa, and differences between the microvascular architecture of the cancerous and noncancerous mucosa are also clear. In addition to the above findings, LBC is clearly present in the noncancerous background mucosa, but absent in the cancerous mucosa, a useful finding for the ready identification of the cancer margins.

14.4.2 Category 3

Cases where the entire tumor margin is indistinct using conventional endoscopy alone (IIb).

14.4.2.1 Category 3.1

Cases where the entire tumor margin can be delineated using magnifying endoscopy (Table 14.4, Figs. 14.12 and 14.13).

Table 14.4

Margin delineation: impossible using conventional endoscopy, delineable using magnifying endoscopy (Category 3.1)

Detect lesion | Characterize | Delineate margins | |

|---|---|---|---|

Conventional endoscopy/dye spraying | ○ | ○ | × |

Magnifying endoscopy | ○ | ○ | ○ |

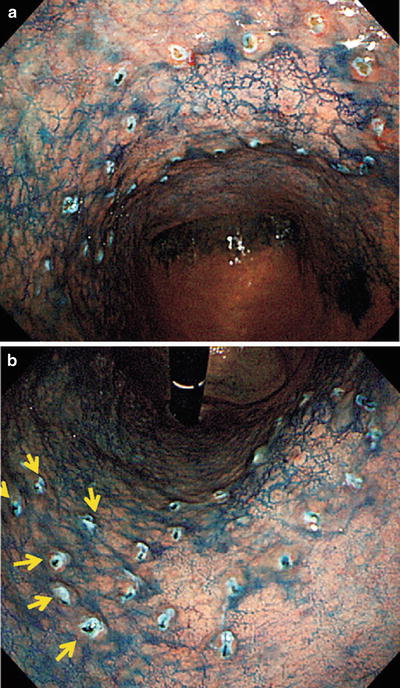

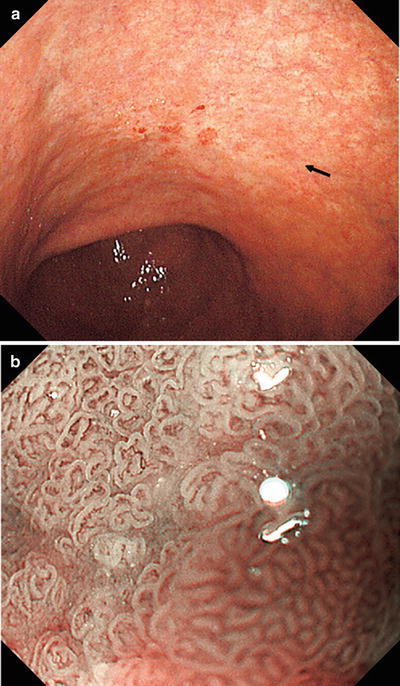

Fig. 14.12

Cases where the tumor margin is unclear in its entirety using conventional endoscopy alone, but the margin can be delineated in its entirety using magnifying endoscopy

Fig. 14.13

Clinical strategy: marking the entire margin using magnifying endoscopy

For cases fitting this category, please refer to Cases 1 and 3 in “6.7 Examples of margin delineation using ME” in Chap. 6.

14.4.2.2 Category 3.2

Cases where almost the entire tumor margin can be delineated using magnifying endoscopy, but it is indistinct in one section (Table 14.5, Figs. 14.14–14.29).

Table 14.5

Margin delineation: impossible using conventional endoscopy, limited using magnifying endoscopy (Category 3.2)

Detect lesion | Characterize | Delineate margins | |

|---|---|---|---|

Conventional endoscopy/dye spraying | ○ | ○ | × |

Magnifying endoscopy | ○ | ○ | Δ |

Fig. 14.14

Cases where the tumor margin is unclear in its entirety using conventional endoscopy alone, whereas the margin can be delineated in almost its entirety using magnifying endoscopy, but part of the tumor margin is indistinct

Fig. 14.15

Clinical strategy: marking entire discernible margin using magnifying endoscopy, then…

Fig. 14.16

Clinical strategy (1): for the part where the margin is unclear, widely mark the background mucosa with RMVP and RMSP

Fig. 14.17

Clinical strategy (2): for the part where the margin is unclear, combine biopsies (X) + wide marking of the background mucosa with RMVP and RMSP

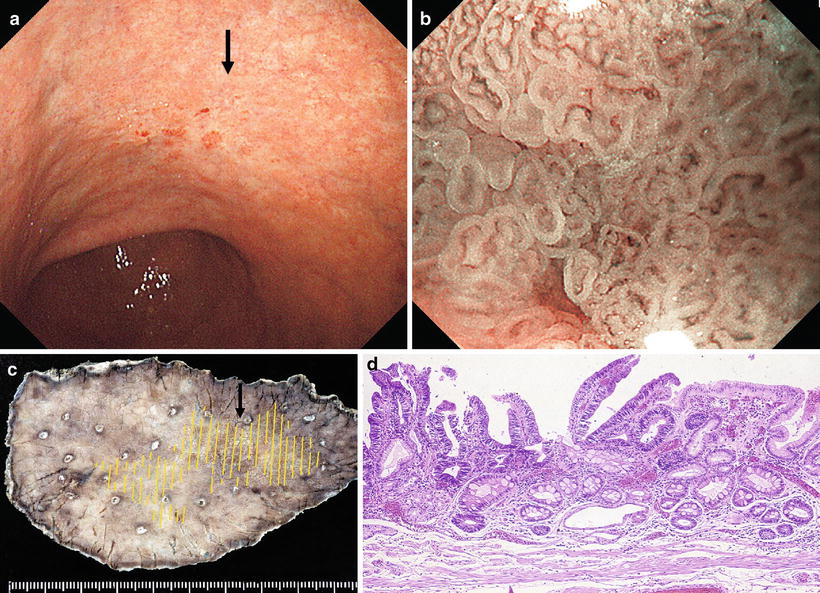

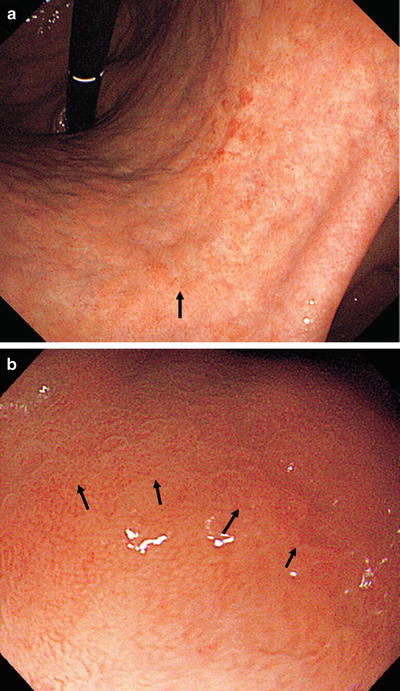

Fig. 14.18

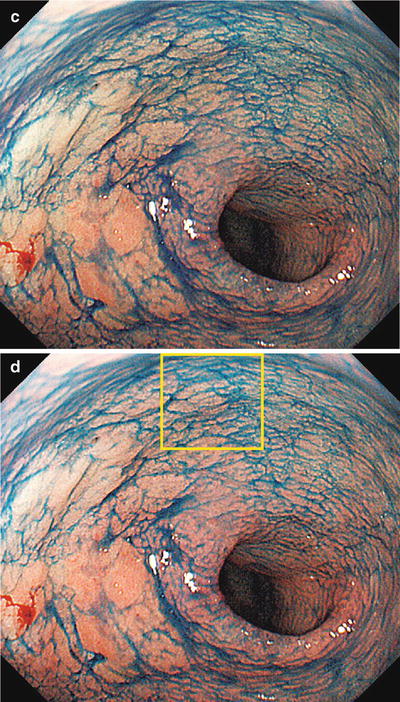

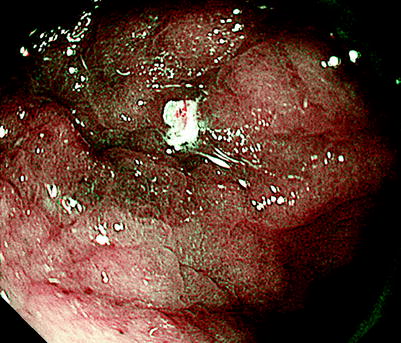

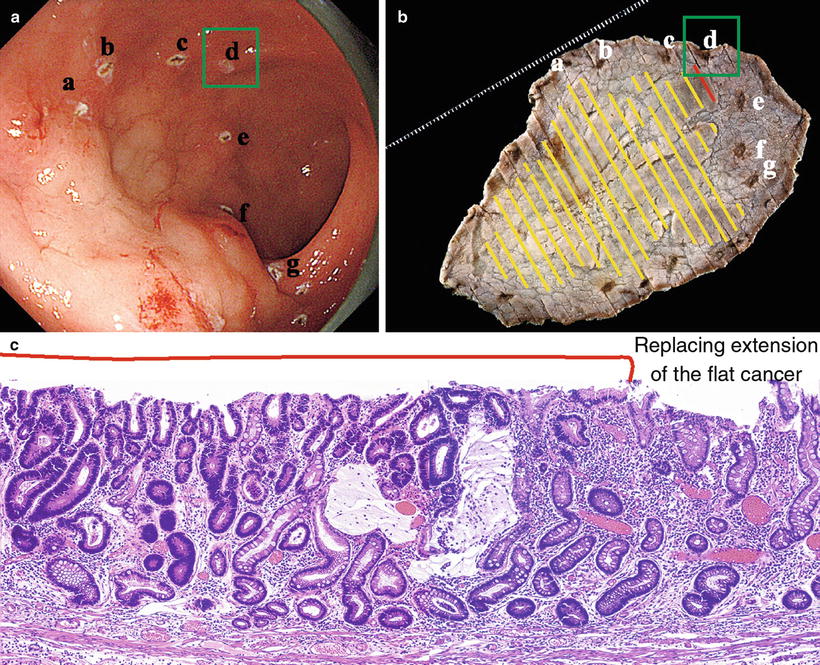

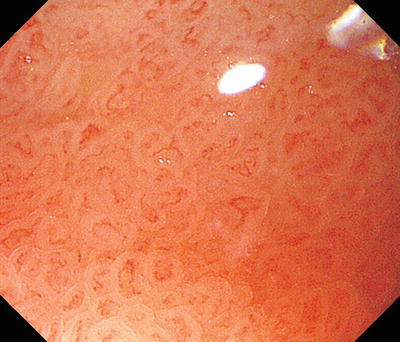

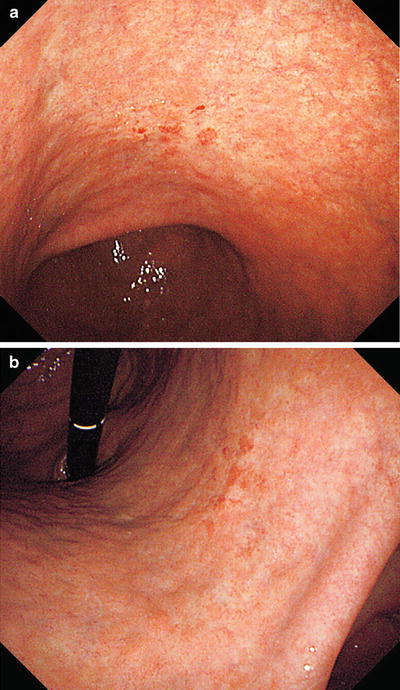

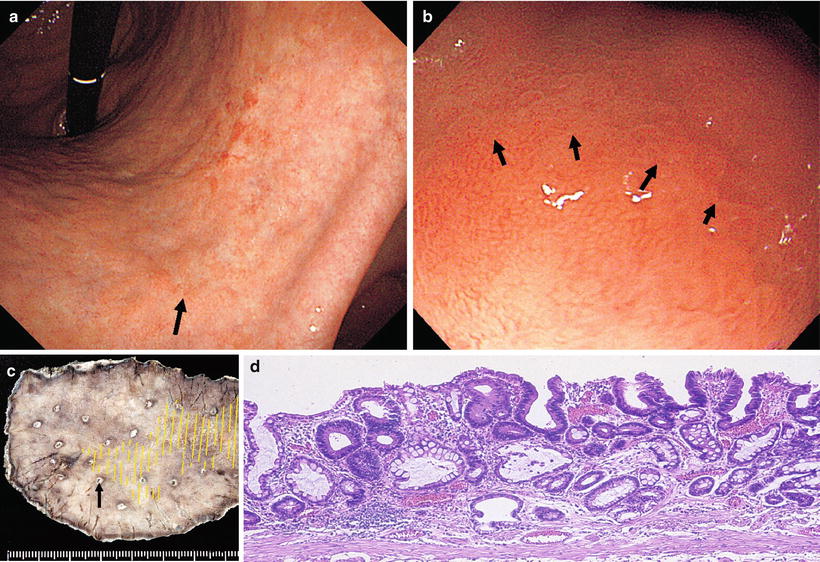

(a, b) Non-magnifying endoscopic findings. On the anterior and posterior walls of the lesser curvature of the gastric body, we can see a mucosal lesion with irregular margins and minimal height variation. It is colored pale or the same as the surrounding mucosa, with reddish granular projections scattered within the lesion

Fig. 14.19

(a, b) Dye spraying. At the oral side of the lesion we can see a depressed margin with irregular projections and a depressed microgranular mucosa within the margin. At the anal side of the lesion, the invasive margin shows little variation in height or mucosal surface structure, and delineation of the margin is more difficult than with standard non-magnifying endoscopy before dye spraying

Fig. 14.20

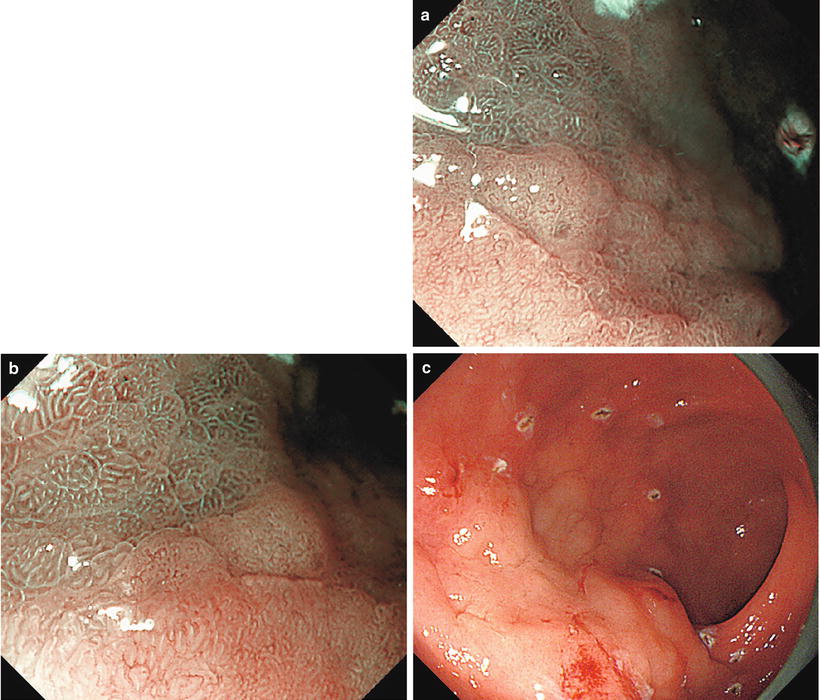

b shows the magnifying endoscopic findings of the area indicated by the arrow in a. Using WLI at low magnification, approaching the lesion from the oral side, we see a clear demarcation line (DL, arrow) where the regular MV pattern plus regular MS pattern is lost

Fig. 14.21

Examination of the microvascular pattern within the DL in b at the maximal magnifying ratio reveals an irregular MV pattern, with irregular morphology, asymmetrical distribution, and an irregular arrangement. The line indicated by the arrows in Fig. 14.20b was assessed as the oral margin of the cancer

Fig. 14.22

Changing over to M-NBI, in addition to the internal irregular MV pattern, we can identify an irregular MS pattern, with curved to oval MCE morphology, indicating a fairly well-differentiated tubular or papillary adenocarcinoma

Fig. 14.23

b shows the M-NBI findings of the area indicated by the arrow in a. The regular MV pattern plus regular MS pattern is lost at the DL, within which we see an irregular MV pattern plus irregular MS pattern. The MCE shows a curved to oval morphology, and we see proliferation of irregular vessels corresponding to the small narrow IP subepithelium. These are typical findings of a tubular to papillary adenocarcinoma

Fig. 14.24

(a, b) The margin of this lesion could be delineated almost in its entirety, so where possible markings were placed on the DL under maximal magnification. However, on the anterior wall side in a, the DL became unclear, and in the areas indicated by arrows in b, it was only just possible to discern a slightly different pattern to the adjacent area. In this section, we widely marked the surrounding mucosa where it showed a regular MV pattern plus regular MS pattern

Fig. 14.25

(a, b) Dye spraying following marking. This lesion extends over the anterior and posterior walls of the lesser curvature of the mid-gastric body. The margin is unclear even with magnified examination in the areas indicated by arrows in b, so markings were placed more widely in this region. The lesion was resected on bloc, including these markings, by ESD

Fig. 14.26

ESD specimen fixed in formalin and reconstruction of lesion. All markings can be identified, confirming that the tumor margins were accurately delineated, apart from a section of the anterior wall side. The arrows correspond to the arrows in Fig. 14.25b. The tumor is confined to the inside of the markings

Fig. 14.27

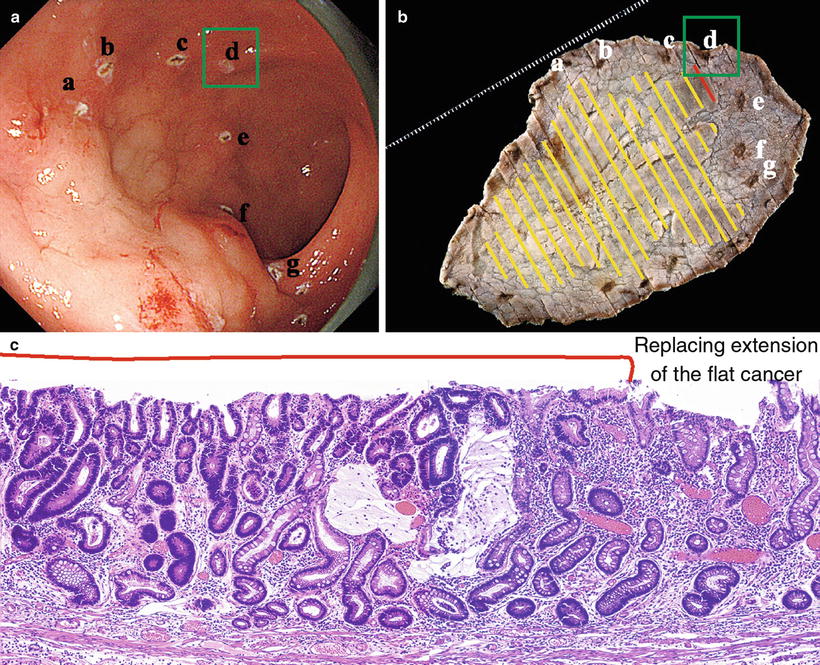

(a–d) Comparison with pathohistological image of the oral margin. M-NBI demonstrated curved to oval MCE, whereas the histological findings are of differentiated papillary to tubular adenocarcinoma. (a) Non-magnifying endoscopic findings. Oral margin (arrow). (b) M-NBI findings. (c) Resected specimen (arrow corresponds to arrow in a). (d) Corresponding histological findings

Fig. 14.28

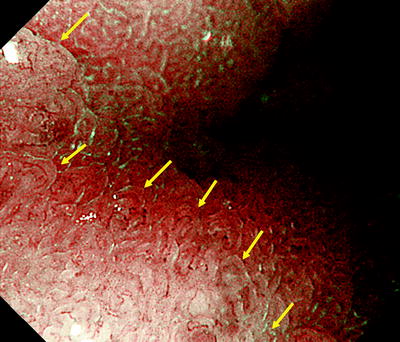

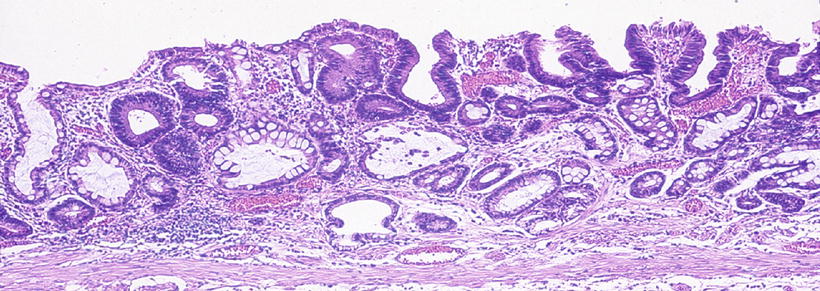

(a–d) Comparison between endoscopic and pathohistological findings in the anterior wall region where magnifying endoscopy could not identify the margins. (a) Non-magnifying endoscopic findings. Anterior wall margin (arrow). (b) M-WLI findings. Anterior wall margin (arrow). (c) Resected specimen (arrow corresponds to arrow in a). (d) Corresponding histological findings

Fig. 14.29

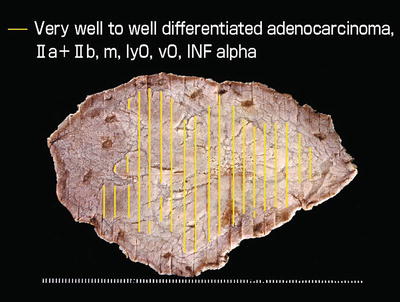

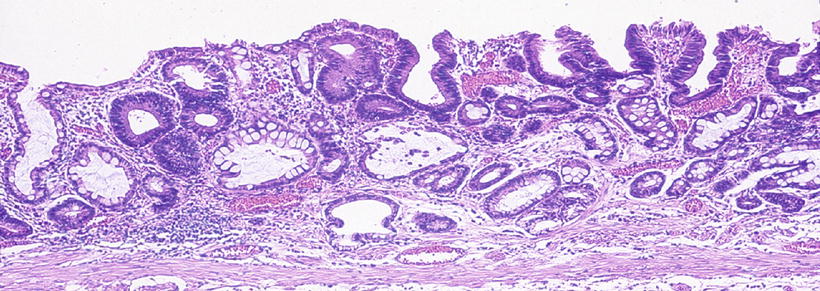

Magnified image of the pathohistological findings in Fig. 14.28d. No difference in height is seen between the tumor and surrounding mucosa. The mildly atypical tumor glands grow replacing the uppermost surface layer and are intermixed with non-tumor glands on the epithelial surface. In other words, this very well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (cancer with low-grade atypia) is growing replacing the mucosal surface, showing a histological picture of an admixture of cancerous and noncancerous glands

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree