FIGURE 11.1 Minimal change disease. Glomeruli are normal by light microscopy in MCD. Note that the glomerular basement membrane is thin and delicate, and mesangial cellularity and matrix are within normal limits (Jones’ silver stain, ×200). (Originally published in Am J Kidney Dis 33(3): E1, 1999. Copyright by The National Kidney Foundation, with permission.) (See Color Plate.)

FOCAL AND SEGMENTAL GLOMERULOSCLEROSIS

FSGS is characterized by proteinuria due to focal (some glomeruli) and segmental (portions of glomeruli) sclerosis. This form of the nephrotic syndrome has been increasing in incidence and is more frequently found in African Americans and other patients of African descent. Various pathologic types of FSGS (tip lesion, cellular variant, collapsing variant, etc.) have now been described (D’Agati et al., 2004). FSGS often progresses to ESKD.

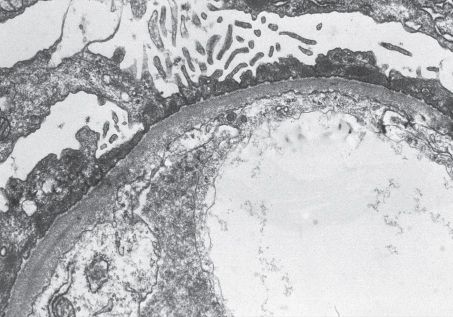

FIGURE 11.2 Minimal change disease. The glomerular basement membrane is of normal thickness without deposits. The visceral epithelial cells show the diffuse effacement of foot processes that occurs in proteinuric states. Foot-process effacement is generally quite extensive in MCD (Transmission electron microscopy, ×800). (Originally published in Am J Kidney Dis 33(3): E1, 1999. Copyright by The National Kidney Foundation, with permission.)

Pathogenesis

FSGS is a pathologic entity that probably has many etiologies (immune, infectious, hemodynamic, genetic, etc.). It is typically divided up into primary (idiopathic) and secondary FSGS. Primary FSGS may be caused by immune/cytokine dysregulation, similar to MCD. However, podocyte ultrastructural changes (such as loss of mature podocyte markers) have been identified in FSGS but not MCD, which may contribute to focal glomerular basement membrane denudation and glomerulosclerosis. In some patients, a circulating glomerular permeability factor seems to be etiologic, and in such cases, rapid recurrence after kidney transplantation is seen. The serum soluble urokinase receptor is one such putative causative factor (Wei et al., 2011). Many cases of secondary FSGS are thought to be due to low nephron number (as in renal agenesis or in patients born with fewer nephrons) leading to intraglomerular hypertension, which results in endothelial and podocyte injury. Hemodynamic alterations also probably underly obesity-associated FSGS. The collapsing variant of FSGS is characteristic of HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN). Finally, antiserum against transforming growth factor β ameliorates experimental FSGS (Border et al., 1990).

Laboratory Evaluation

■ Massive proteinuria (not only predominantly albuminuria but also globulinuria)

■ Decreased serum proteins and immunoglobulins (especially in primary form)

■ Increased serum lipids (especially in primary form)

■ Normal serum complements

■ No serologic abnormalities

Pathology

■ Light microscopy

■ Segmental sclerosis in a focal (some glomeruli) and segmental (parts of glomeruli) pattern (Fig. 11.3)

■ Immunofluorescence

■ Nonsclerotic glomeruli do not stain for IgG or complement

■ Sclerotic segments may have irregular staining for IgM, C3, C1q

■ Electron microscopy

■ There is foot process effacement

■ Electron microscopy is generally used to identify other causes for glomerular scarring

Treatment

■ Exclude secondary causes

■ Test for HIV (if positive, treatment directed at HIV)

■ In massive obesity, weight loss (with or without bariatric surgery) can improve outcomes

■ Stop medications associated with FSGS (anabolic steroids, pamidronate)

■ Primary FSGS may respond to immunosuppressive therapy, though not as well as MCD

■ Children—prednisone (same as in MCD) is treatment of choice. Relapse or steroid resistance is also treated as in MCD.

■ Adults—steroids have been moderately successful. A longer course of therapy with higher doses of prednisone (up to 4 months) will be required. Remission rates have been reported to be as low as 15% to up to 40%. Elderly patients may respond to alternate day steroid therapy. Other immunosuppressives (calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide) have been used

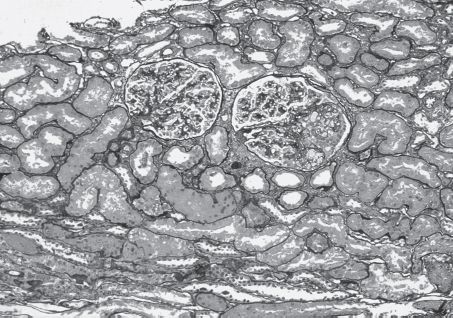

FIGURE 11.3 Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. The larger of the two glomeruli shown contains two small peripheral foci of segmental sclerosis with intracapillary foam cells and prominence of overlying visceral epithelial cells. This is representative of an early segmental sclerosing lesion in FSGS. There is also surrounding mild interstitial fibrosis (Jones’ silver stain, ×100) (Copyright © 1999 by the National Kidney Foundation). (Originally published in Am J Kidney Dis 33(4): E1, 1999. Copyright by The National Kidney Foundation, with permission.)(See Color Plate.)

MEMBRANOUS NEPHROPATHY

MN is the most common form of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in Caucasian adults (FSGS is more common in African Americans). There are a multitude of secondary causes of MN. In the US, the most common are lupus, hepatitis B, and malignancy (especially in older patients).

Pathogenesis

MN is characterized by the presence of immune deposits in the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) in a subepithelial location. Experimental models have suggested that these immune deposits develop in situ, with movement across the GBM of circulating IgG antibodies directed against endogenous podocyte antigens or against circulating antigens that have crossed the GBM. Antigens that have been implicated in MN include the phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R) and neutral endopeptidase. The M-type PLA2R, a transmembrane receptor that is highly expressed in podocytes, has been identified as a major antigen in human idiopathic MN. Circulating autoantibodies to PLA2R were identified in 70% of patients with idiopathic MN and was associated with disease (Beck et al., 2009). Subsequent studies have confirmed anti-PLA2R antibodies in 60% to 80% of patients with idiopathic MN. Other antigens have been identified in secondary MN, including double-stranded DNA in lupus, thyroglobulin in thyroiditis, hepatitis B antigen, treponemal antigen in syphilis, and carcinoembryonic antigen and prostate-specific antigen in malignancy, though causality has not universally been established. The end result of immune complex formation is complement activation and injury to glomerular epithelial cells (Cybulsky et al., 1986).

Laboratory Evaluation

■ Proteinuria (subnephrotic to massive)

■ Hypoalbuminemia

■ Hyperlipidemia

■ Check for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, rapid phase reagin (RPR) (syphilis), HIV, antinuclear antibodies, complements (normal complements are seen in idiopathic MN, but may be low in some secondary causes)

Pathology

■ Light microscopy

■ Capillary wall thickening

■ Immunofluorescence

■ Diffuse granular capillary wall staining for IgG and complement

■ In MN caused by lupus, there is usually high-intensity staining for C1q

■ Electron microscopy

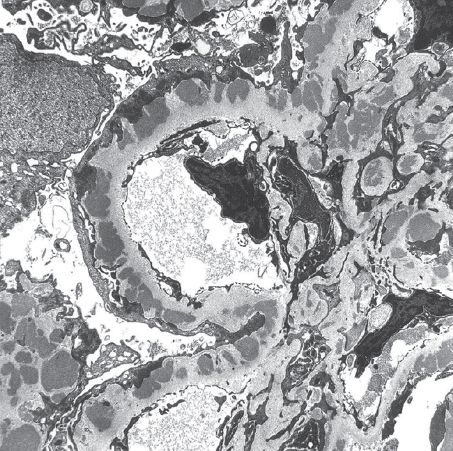

■ Subepithelial immune complex deposits with foot-process effacement (Fig. 11.4).

■ Immune complexes may be due to antigens to hepatitis B, tumor antigen, or autoantigen.

■ In secondary MN, the immune complexes may also be in the mesangium.

FIGURE 11.4 Membranous nephropathy. Stages II to III membranous glomerulonephritis with thickened capillary wall resulting from numerous medium to large subepithelial dense deposits and basement membrane reaction (transmission electron microscopy, original magnification ×1,650). (Originally published in Am J Kidney Dis 31(3): E1, 1998. Copyright by the National Kidney Foundation, with permission.)

Exclude secondary causes, especially in older patients (malignancy) and patients with risk factors for hepatitis. Idiopathic MN may be indolent and not require treatment. Immunosuppressive treatment is indicated in certain high-risk groups (hypertension, low GFR, massive proteinuria, interstitial scarring on renal biopsy). Treatment options include alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide), calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolate, and rituximab, often in combination with steroids. Steroids alone are not beneficial. ACE-inhibitors and lipid-lowering agents are also recommended.

AMYLOIDOSIS (AL OR AA TYPE)

Amyloidosis refers to diseases caused by extracellular deposition of fibrils within organs. Fibrils are proteins that have an antiparallel β-pleated sheet configuration that enhances deposition in organs (Husby et al., 1994); these fibrils are resistant to degradation and bind Congo Red and Thioflavin T. There are many hereditary amyloidoses, and mutations in diverse proteins may produce amyloid. Only select amyloid fibrils deposit in the kidney. Amyloidoses that affect the kidneys include AL amyloidosis and AA amyloidosis.

Pathogenesis

In AL amyloidosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree