Miscellaneous Nontumors and Tumors

NONTUMORS

Amyloidosis

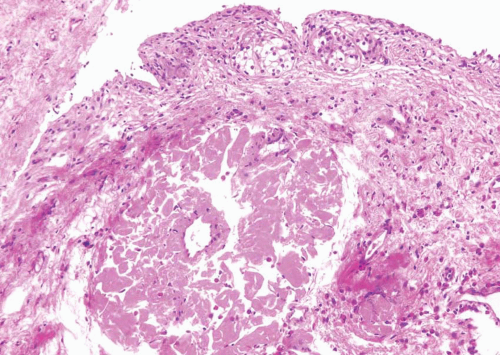

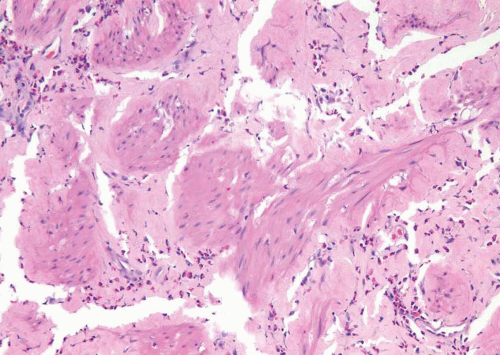

The bladder can be involved in cases of systemic amyloidosis but rarely is the primary site of this disease (1). The usual clinical presentation is that of hematuria. On cystoscopy, a localized amyloid tumor will be seen as an elevated mass that can be confused with an invasive neoplasm. Less frequently, the disease may diffusely involve the bladder wall. Microscopically, the amyloid protein is an eosinophilic, afibrillar, homogeneous material deposited preferentially in the lamina propria and extending into the connective tissue surrounding muscle fascicles (2) (Figs. 12.1, 12.2) (efigs 12.1-12.7). Less frequently, and usually in systemic amyloidosis, there are perivascular amyloid deposits. Congestion and hemorrhage are common but inflammatory cells are scanty unless the overlying epithelium is ulcerated. A few fibroblast-like cells are usually interspersed within the eosinophilic material. Special stains such as Congo red, crystal violet, or van Gieson will help establish the diagnosis. Patients with localized lesions are usually successfully managed by transurethral resection (TUR), but patients with more diffuse involvement may require more radical surgery to control the bleeding (3).

Diverticular Disease

Bladder diverticula are relatively common yet their etiology remains controversial. Most investigators agree that they occur secondary to an increased intravesical pressure as a result of obstruction, distal to the diverticulum (4, 5, 6). The obstruction brings about compensatory muscle hypertrophy and eventual mucosal herniation in areas of weakness. Others feel that at least some diverticula are a consequence of congenital defects in the bladder musculature and they cite as evidence cases of diverticula in young patients without evidence of obstruction (7, 8). The most common sites of diverticula are adjacent to the ureteral orifices, the bladder dome (probably related to a urachal remnant), and the region of the internal urethral orifice. Grossly, one sees distortion of the external surface of the bladder. The diverticula may be widely patent but are usually narrow in

symptomatic patients. The mucosa adjoining the diverticulum is usually hyperemic or ulcerated. There may be epithelial hyperplasia adjacent to the diverticula and the underlying muscularis propria is hypertrophic. Very commonly, there is inflammation involving the lamina propria and muscularis in the area of the diverticular os. The wall of the diverticulum itself consists of urothelium and underlying connective tissue, similar to the bladder mucosa with lamina propria. Few muscle fascicles will be identified in the majority of cases of acquired diverticula but, when present, represent muscularis mucosae which may become hyperplastic. In fact, in some cases these hyperplastic muscularis mucosae may appear as a relatively thick, continuous layer of smooth muscle. The true “congenital” diverticula contain a thinned outer muscle layer. The epithelium lining the

sac may undergo squamous or glandular metaplasia due to local irritation associated with urine stasis, infection, or stone. In these cases, it is not unusual for the diverticular wall to become extensively fibrotic.

symptomatic patients. The mucosa adjoining the diverticulum is usually hyperemic or ulcerated. There may be epithelial hyperplasia adjacent to the diverticula and the underlying muscularis propria is hypertrophic. Very commonly, there is inflammation involving the lamina propria and muscularis in the area of the diverticular os. The wall of the diverticulum itself consists of urothelium and underlying connective tissue, similar to the bladder mucosa with lamina propria. Few muscle fascicles will be identified in the majority of cases of acquired diverticula but, when present, represent muscularis mucosae which may become hyperplastic. In fact, in some cases these hyperplastic muscularis mucosae may appear as a relatively thick, continuous layer of smooth muscle. The true “congenital” diverticula contain a thinned outer muscle layer. The epithelium lining the

sac may undergo squamous or glandular metaplasia due to local irritation associated with urine stasis, infection, or stone. In these cases, it is not unusual for the diverticular wall to become extensively fibrotic.

Major complications of bladder diverticula include infection, lithiasis with subsequent obstruction, and carcinoma (9, 10, 11). It is believed that 2% to 7% of patients with bladder diverticula will develop an associated urothelial neoplasm, presumed secondary to the chronic inflammatory stimuli mentioned above. The neoplasms may develop at the orifice or may occur within the diverticula, making endoscopic evaluation difficult. While “usual” urothelial carcinomas predominate, there is a relative increase in urothelial tumors with divergent differentiation in the form of squamous carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, at times associated with squamous or glandular metaplasia in the lining urothelium. Rare cases of small cell carcinoma have been described. Sarcomas and at least one sarcomatoid carcinoma have also been reported in association with bladder diverticula, but we feel that most, if not all, of these cases are likely to represent sarcomatoid transformation in high-grade urothelial carcinomas (11). Survival is dependent on the stage at the time of resection, with tumors invading the lamina propria (pT1) having a better disease-specific survival than tumors that extend into the peridiverticular soft tissue (pT3) (12, 13).

Ectopic Prostatic Tissue

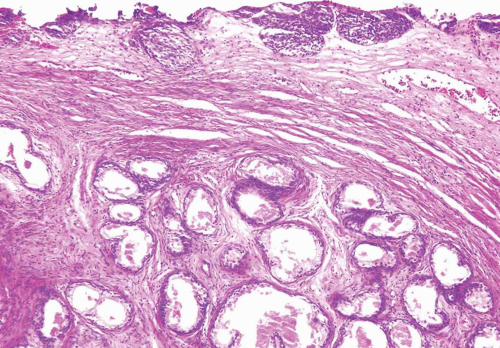

Ectopic prostatic polyps within the bladder are usually single, polypoid lesions usually around the trigone (14). These lesions typically present with gross and microscopic hematuria. The lesions may occur over a wide age range. Histologically, the submucosal component of the urethral polyps is composed of stroma and prostatic glands (Fig. 12.3). The glands may be closely packed and, in some areas, they may be cystically dilated at the periphery. The surface of urethral polyps is often papillary with broad

papillae lined by urothelial cells, prostatic epithelial cells, or a combination of both. Rarely, these polyps have broad finger-like villous projections lined by benign prostatic epithelium. The presence of corpora amylacea and double-layered epithelium is a helpful clue to the prostatic origin of the lesions. These lesions are totally benign.

papillae lined by urothelial cells, prostatic epithelial cells, or a combination of both. Rarely, these polyps have broad finger-like villous projections lined by benign prostatic epithelium. The presence of corpora amylacea and double-layered epithelium is a helpful clue to the prostatic origin of the lesions. These lesions are totally benign.

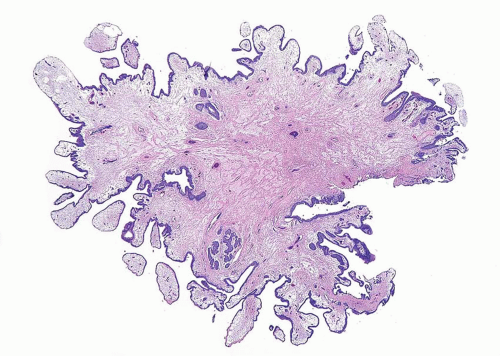

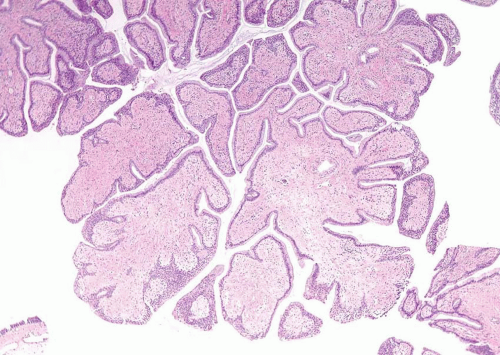

Fibroepithelial Polyp

Fibroepithelial polyp of the lower urinary tract is a relatively rare disease entity that is considered to be a nonneoplastic condition, some of which arise from acquired conditions and others congenitally (15). There is a marked male predominance. More than half of the reported cases occur in neonates or children, some of which are associated with urogenital malformations. However, cases have also been reported from the second to the fourth decades. Their main clinical manifestations are urinary obstruction, urinary hesitancy, dysuria, enuresis, hematuria, infection, and flank pain. They are usually diagnosed by cystourethrography or cystoscopy and are treated by TUR, following which the lesion does not usually recur. Most cases are located near the verumontanum or the bladder neck. Histologically, fibroepithelial polyps are predominantly composed of urothelial epithelium and fibrovascular stroma showing a finger-like or polypoid growth pattern (Figs. 12.4, 12.5 and 12.6) (efigs 12.8-12.11). Urothelium shows tubular or anastomosing structures with colloid-like secretions in some cases, resembling cystitis glandularis. Although some of urothelium shows focal squamous or mucinous metaplasia or becomes thin or denuded, none contains significant cytological atypia. The stroma of the polyps typically contains relatively frequent small vessels, some of which are dilated or congested. Stromal edema, either focal or extensive, is also a common finding. Although the stromal cells can show atypia with

multinucleated cells and hyperchromasia, the atypia appears degenerative in nature, lacking prominent nucleoli and mitoses.

multinucleated cells and hyperchromasia, the atypia appears degenerative in nature, lacking prominent nucleoli and mitoses.

Urothelial papilloma may be difficult to differentiate because both lesions show a polypoid or finger-like growth pattern and lack of cytological atypia of the urothelium. However, urothelial papilloma usually has thin fibrovascular cores in contrast to the relatively broad stroma of the fibroepithelial polyp.