Miscellaneous Esophageal Disorders

Esophageal Diverticula

Esophageal diverticula are out-pouchings of the esophageal wall. They may contain all histologic sections of the wall or may lack the muscularis layer. These can be classified on the basis of their location or etiology. The most common classification is anatomical and divides esophageal diverticula into hypopharyngeal (Zenker’s diverticulum), midesophageal diverticula, and epiphrenic diverticula.

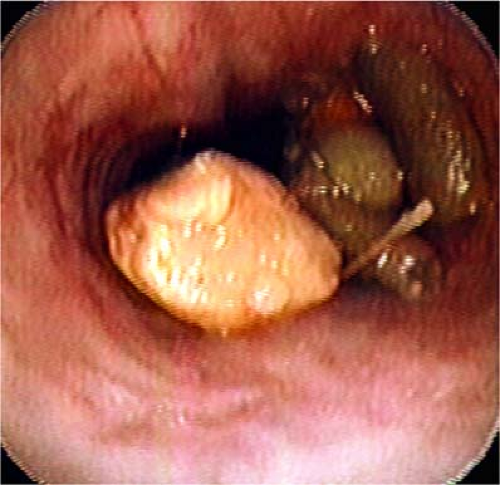

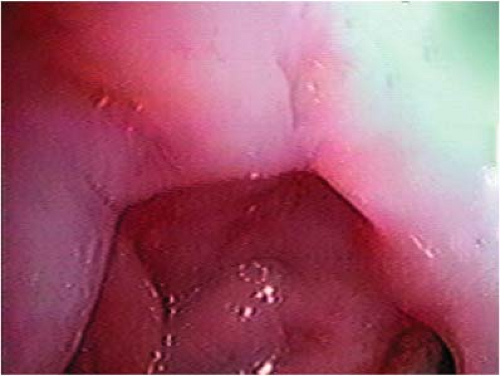

Zenker’s diverticula are a protrusion of the hypopharyngeal mucosa in the area of congenital weakness (Killians’ dehiscence) between the inferior pharyngeal constrictor and the cricopharyngeus muscle. The presence of a diverticulum should always be suspected in patients with dysphagia and regurgitation or frequent coughing while eating. During transnasal esophagoscopy (TNE), if the examiner has difficulty intubating the esophagus, the patients very often will have either an undiagnosed Zenker’s diverticulum or a hypertonic upper esophageal sphincter (1). During the initial part of the esophagoscopy, if the examiner sees food or copious secretions, then she/he should suspect that they are in a diverticulum, and great care should be taken not to cause a perforation of this “false lumen.” Suctioning and judicious use of air insufflation coupled with a clockwise twisting of the esophagoscope should allow the esophageal lumen to come in to view. The examiner should not aggressively advance the esophagoscope if the lumen is not visible to avoid perforation. Figure 9.1 demonstrates a Zenker’s diverticulum during TNE.

Figure 9.1 Zenker’s diverticulum. The neck of the diverticulum opens into a large pouch. The esophageal lumen is to the patient’s right. |

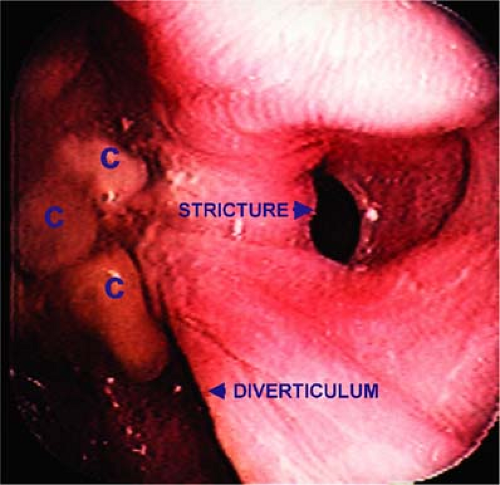

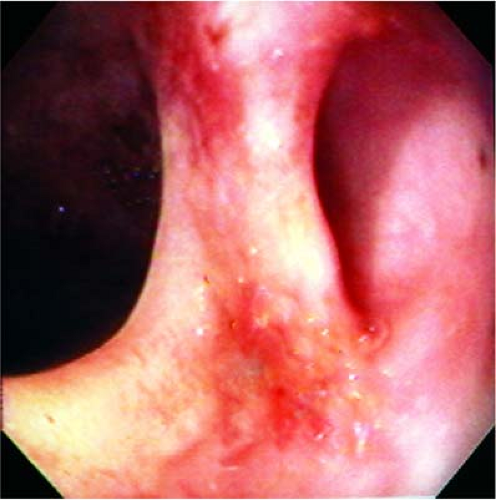

Dysphagia following the endoscopic treatment of these diverticula is uncommon but may result from scar formation across the site of the stapled diverticulotomy, as demonstrated in this patient 3 years after surgery (Fig 9.2).

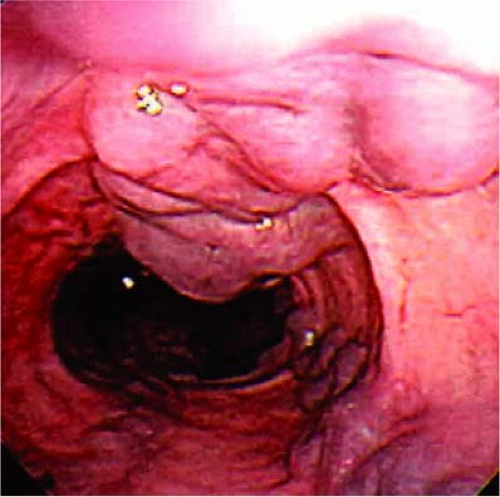

The majority of midesophageal diverticula are asymptomatic due to the wide opening into their sacs. They generally represent old granulomatous disease that retracts the esophageal wall. They are usually diagnosed incidentally during a contrast esophagram (Fig. 9.3). Epiphrenic diverticula are often associated with esophageal motility disorders such as achalasia or diffuse esophageal spasm. Such diverticula can also develop proximal to esophageal strictures (Fig. 9.4).

Figure 9.2 Postsurgical scarring adjacent to the lumen of the esophagus, allowing the diversion of some food into the pouch. |

Figure 9.3 An asymptomatic epiphrenic diverticulum seen during esophageal screening in a patient with gastroesophageal and laryngopharyngeal reflux. |

Esophageal Foreign Body

We do not advocate the removal of foreign bodies from the esophagus in the clinic using currently available technology. However, we use TNE to evaluate individuals who have a questionable history of foreign body ingestion and in patients whom we believe the foreign body is located in the distal esophagus and can be gently advanced into the stomach (2,3). Total or near-total obstruction may result in accumulated secretions and food that the examiner is unable to fully remove with the small-caliber suction channel. This may make evaluation and pushing the object into the stomach impossible.

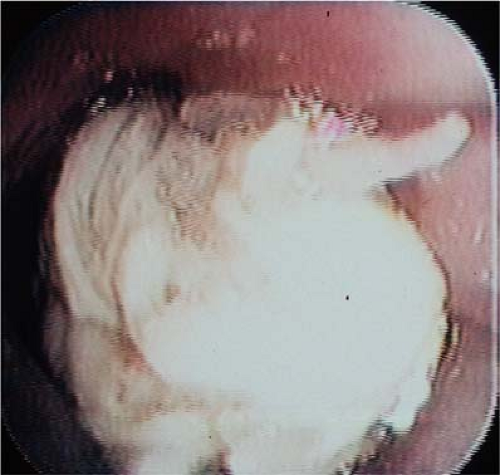

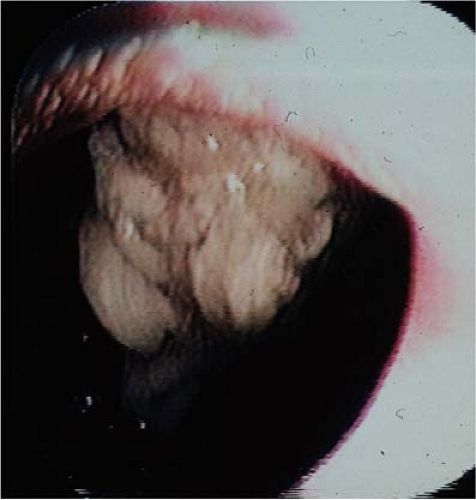

The majority of adults having a foreign body impaction have a definite etiology for their difficulties. This is usually secondary to inflammation from gastroesophageal reflux, peptic or malignant stricture, esophageal dysmotility, neoplasm, or Schatzki’s ring. It is important that the cause for the obstruction be established to enable appropriate therapy. Our technique involves gently suctioning any debris adjacent to the foreign body, and care is taken not to force the foreign body into a carcinoma or into an unappreciated esophageal diverticulum (Fig. 9.5). Air is insufflated to dilate the esophagus. The esophageal mucosa around the foreign body can then be evaluated. When the surgeon’s clinical judgment is such that the foreign body can be advanced into the stomach, it is done with a combination of air insufflation, gentle pushing with the endoscope, and grasping with the biopsy forceps (Figs. 9.6 and 9.7). After the foreign body is advanced into the stomach, the entire area is reexamined to make a diagnosis and to evaluate the area for signs of trauma. If any difficulty occurs, the patient is taken to the operating room for rigid endoscopy. Metallic or sharp foreign bodies are taken to the OR for rigid endoscopy and are not managed with TNE.

Tracheoesophageal Fistula

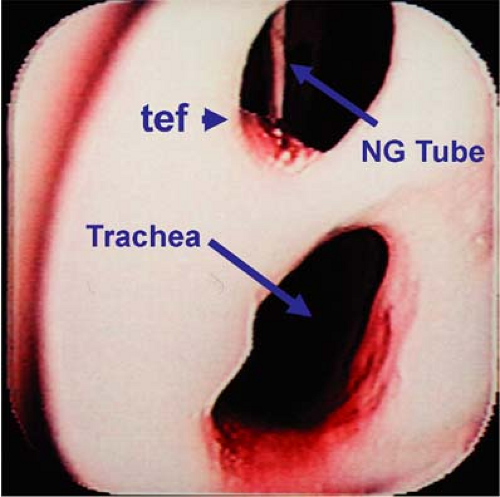

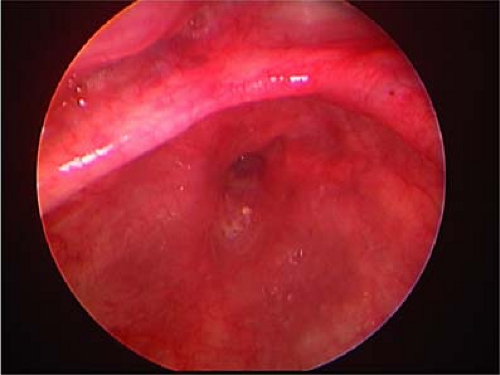

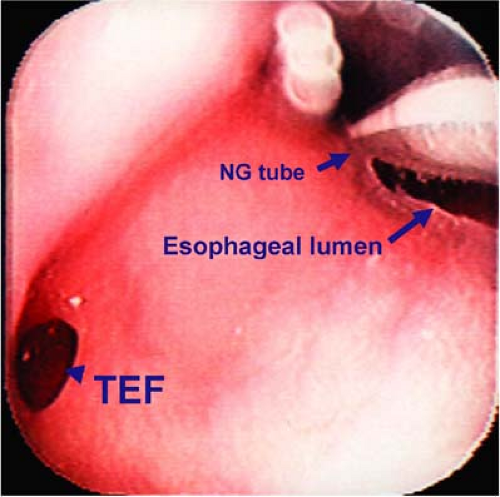

Tracheoesophageal fistulas are fortunately uncommon entities. They are usually the consequence of a malignancy eroding the common wall between the trachea and esophagus. Less common etiologies would include chronic foreign bodies and trauma. Patients usually present with varying degrees of aspiration, dysphagia, chronic cough, frequent belching, or painful swallowing. The diagnosis is usually made via a barium swallow. Endoscopy can also provide the diagnosis. Small tears in the esophageal lumen can be missed unless a significant amount of air insufflation is provided to distend the esophagus. Bubbles may be seen in the secretions. Larger endoscopes can do this easily, while transnasal endoscopes are not as effective at significantly distending the esophagus with air. Figures 9.8 and 9.9 demonstrate a tracheoesophageal fistula from both the esophageal and tracheal view. This was a traumatic fistula which occurred during the dilation of this individual’s tracheal stenosis and was not identified on barium swallow.

Esophageal Varices

Gastroesophageal variceal bleeding is a commonly encountered problem in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Varices are due to dilation of the collateral circulation between the portal vein and vena cava. Nearly all patients with cirrhosis will eventually develop esophageal varices. Fifty percent of cirrhotic patients will have endoscopic evidence of varices at the time of initial diagnosis. The risk of bleeding from these distended

submucosal veins is significant, and the overall mortality for a first variceal hemorrhage ranges from 17% to 57%. Many patients with esophageal varices will suffer from recurrent hemorrhage (4, 5).

submucosal veins is significant, and the overall mortality for a first variceal hemorrhage ranges from 17% to 57%. Many patients with esophageal varices will suffer from recurrent hemorrhage (4, 5).

Figure 9.8 The esophagoscope is in the esophagus and the nasogastric tube and tracheoesophageal fistula are seen. |

There remains controversy in the gastroenterologic literature regarding the proper care of patients with esophageal varices. Options include surveillance endoscopy, treatment with beta blockers, and preemptive treatment with various types of endoscopic therapy. In light of this, it is vital that the endoscopist be able to recognize these lesions and also avoid biopsying them during the course of a TNE. Esophageal varices appear as irregular, sometimes linear, sometimes tortuous submucosal lesions with a bluish hue. They may collapse with air insufflation. They can appear anywhere along the entire length of the esophagus, as well as in the gastric cardia, and as they enlarge, they can project into the lumen of the esophagus. Although varices do not typically break the mucosa, they can appear to be ulcerated if they have recently bled (Figs. 9.10 and 9.11). TNE may be the examination method of choicein cirrhotic patients and in patients following liver transplantation for variceal surveillance, since no sedation is needed in these often very ill and frail individuals. Care must be taken to not traumatize the nose, which could lead to difficult control of epistaxis in these patients.

Ultrathin endoscopy represents an advance in the diagnosis of esophageal disease, but the small operating channel does not allow therapeutic intervention for any type of bleeding. We recommend that submucosal lesions not be biopsied. These lesions should be evaluated with larger therapeutic endoscopes that can be used to control any significant bleeding during the specimen acquisition.

Anastomotic Evaluation

Transnasal esophagoscopy is a straightforward way to assess the suture line after hypopharyngeal and gastroesophageal surgery. The most common suture line that is assessed is the pharyngoesophageal segment after total laryngectomy (Fig. 9.12). In patients who have had a free-flap reconstruction or gastric pull-up after esophagectomy, TNE is a simple, easy way to evaluate the suture line and examine the region for recidivistic disease and strictures (Fig. 9.13) (6, 7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree