Chapter 4 Minimally Invasive Ivor Lewis Esophagectomy

Operative indications

Esophagectomy may also be performed in patients with Barrett esophagus with high-grade dysplasia. In patients with diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia or early-stage tumors confined to the mucosa (T1a), satisfactory results have also been reported with endoscopic mucosal resection, radiofrequency ablation, and laparoscopic transgastric stripping of esophageal mucosa (see Chapter 6). Thus far, however, there have been only a few reports with good follow-up, and even these only report short- to intermediate-term outcomes. Although endoscopic mucosal resection and radiofrequency ablation offer several immediate benefits to the patient, there are concerns that subsquamous Barrett esophagus may still progress to adenocarcinoma, and continued surveillance endoscopy is required. When endoscopic mucosal resection is performed for early-stage tumors confined to the mucosa, incomplete resection is a concern. Moreover, high-grade dysplasia is often multifocal, and there is a high rate of occult carcinoma in patients who undergo resection for the preoperative diagnosis of high-grade dysplasia. Therefore, we continue to offer MIE for multifocal high-grade dysplasia and early-stage adenocarcinoma. We reserve other ablative therapies for those patients who are unwilling to undergo esophagectomy or are poor candidates for surgery.

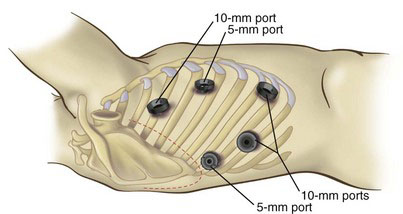

Placement of trocars

For the laparoscopic portion of the procedure, six abdominal trocars (three 5 mm and three 10 mm) are placed. First, a 10-mm port through a Hasson technique in placed in the right paramedian position. In the average patient, this approximates two thirds the distance from the xiphoid to the umbilicus. In obese patients with a very protuberant abdomen, this two-thirds distance must be reconsidered, and the port likely will have to be moved closer to the upper abdomen. The pneumoperitoneum is established and maintained at a pressure of 15 mm Hg. In patients with cardiopulmonary compromise, the pneumoperitoneal pressure may have to be lowered to under 10 mm Hg. The remaining ports are then placed. A 10-mm port is placed 5 cm to the left of the operating port (30-degree camera port); a 10-mm port is placed 6 cm below the Hasson port to facilitate placement of the jejunostomy tube; and 5-mm ports are placed subcostally on the right and left midclavicular lines (tissue grasper ports). Finally, we place a 5-mm port, for liver retraction, in the right flank, just below the costal margin laterally (Fig. 4-1).

FIGURE 4-1 Port placement for the laparoscopic phase of Ivor Lewis minimally invasive esophagectomy.

(From Wizorek JJ, Awais O, Luketich JD: Minimally invasive esophagectomy. In Zwischenberger JB, editor: Atlas of Thoracic Surgical Techniques, 1st edition. Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders, pp 305–319.)

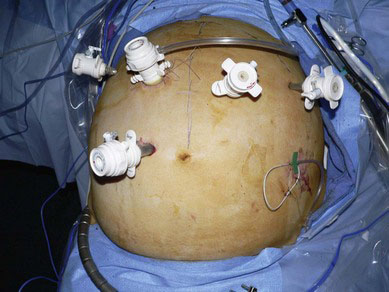

For the thoracoscopic portion of the Ivor Lewis MIE, five ports are used (Fig. 4-2). Correct thoracoscopic port placement is critical because poorly positioned trocars lead to difficulty maneuvering instruments through the rigid chest wall. A 10-mm port is placed in the eighth intercostal space on the posterior axillary line. This is used as the laparoscope port. A 10-mm working port for the ultrasonic shears is introduced in the ninth intercostal space, 6 cm posterior to the posterior axillary line—just inferior to the tip of the scapula. Ultimately, this port is enlarged to a 5-cm access incision to enable passage of the end-to-end anastomotic stapler and removal of the specimen. A 5-mm port is inserted posterior to the scapular tip, and through this port, the surgeon provides countertraction, using instruments held in his or her left hand. A 10-mm port is inserted in the fourth intercostal space on the midaxillary line, and the surgeon uses this port for retraction during the esophageal dissection. Finally, a 5-mm port is inserted at the midaxillary line near the sixth rib to be used as a suction-irrigator port.

Operative technique

On-Table Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Laparoscopic Phase

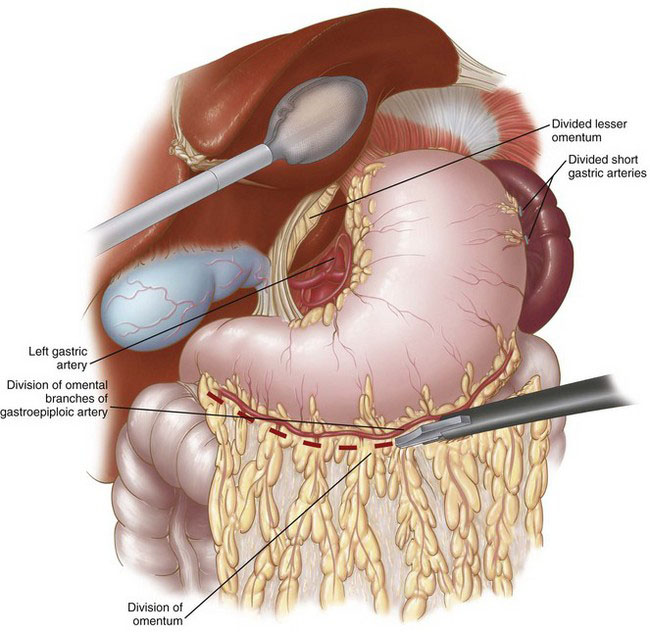

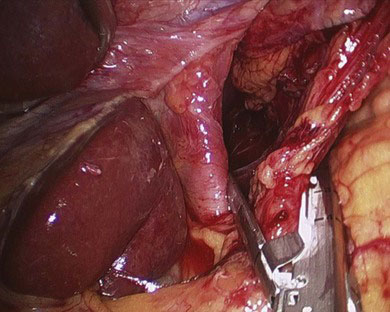

The laparoscopic portion of the procedure is carried out first. Patient positioning and port placement were described previously. A thorough laparoscopic exploration is performed to evaluate for the presence of occult metastatic disease, and then gastric mobilization is carried out. The gastrohepatic ligament (lesser omentum) is first divided, and the right and left crura of the diaphragm are dissected. The GEJ is mobilized, and then the esophagus is dissected circumferentially in the lower mediastinum. The greater curvature of the stomach is then mobilized by first dividing the short gastric vessels, followed by division of the gastrocolic omentum while carefully preserving the right gastroepiploic arcade (Fig. 4-3). The mobilized stomach is retracted toward the liver. The mobility of the pylorus can be used as a good guide for the adequacy of dissection. If the pylorus easily reaches the right crus and caudate lobe of the liver, the mobilization is generally adequate. If there is any tension during this maneuver, then remaining attachments between the posterior wall of the stomach and the pancreas may have to be divided. An extensive Kocher maneuver may be necessary to accomplish complete pyloric-antral mobilization. Prior gallbladder surgery frequently limits the pyloric-antral mobility, requiring additional adhesiolysis in this area. Next, a complete celiac lymph node dissection is performed, continuing along the superior border of the splenic artery and pancreas toward the splenic hilum. The lymph node packet is included in the specimen. The left gastric vessels are then identified, dissected, and divided with the use of a laparoscopic stapler with vascular staple load (Fig. 4-4).

FIGURE 4-4 Division of the left gastric vessels using a vascular load stapler.

(From Wizorek JJ, Awais O, Luketich JD: Minimally invasive esophagectomy. In Zwischenberger JB, editor: Atlas of Thoracic Surgical Techniques, 1st edition. Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders, pp 305–319.)

Attention is then turned to mobilization of the pyloric-antral area and subsequent pyloroplasty. During this mobilization, the surgeon must be diligent in identifying and preserving the right gastroepiploic arcade. The pyloroplasty is started by placing two traction sutures (2-0), one superiorly and one inferiorly, on the pylorus with the Endo Stitch (Covidien, Norwalk, Conn.). The pyloroplasty is performed by opening the pylorus longitudinally with ultrasonic shears and closing it transversely with interrupted sutures using the Endo Stitch device in a Heineke-Mikulicz fashion (Fig. 4-5). A 4- to 5-cm diameter gastric conduit is then constructed. Initially, the very thick and muscular antrum is divided with the use of thick tissue staple loads (4.8 mm). This division begins from the lesser curve above the antrum and proceeds toward the fundus. As this division proceeds cephalad, the thickness of the stomach wall decreases, and 3.5-mm staple loads are more appropriate (Fig. 4-6). To facilitate exposure, staple alignment, and conduit length during this step, the assistant grasps the fundus of the stomach along the line of the short gastric arteries and retracts gently cephalad while another assistant simultaneously grasps the antrum and retracts inferiorly (Fig. 4-7). This essentially elongates the entire stomach and provides the alignment necessary to construct a consistent-diameter gastric conduit. It is recommended that 45-mm staple loads be used in creating the gastric conduit to prevent “spiraling,” which may occur with the use of the 60-mm loads. The tip of the gastric conduit is then secured to the specimen using an Endo Stitch. During this step, care is taken to maintain alignment so that subsequent retrieval of the specimen through the hiatus into the chest does not lead to rotation; this maintains perfect anatomic alignment of the gastric conduit, with the short gastric vessels facing the direction of the spleen and the lesser curve staple line facing the right side of the chest.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree