(1)

Department of Endoscopy, Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital, Fukuoka, Chikushino, Japan

6.6 Preoperative Evaluation of Early Gastric Cancer: Delineation of Cancer Margins (White-Light Imaging)

Summary

Diagnostic markers—V: microvascular architecture

1.

Differentiated (intestinal type) carcinoma

1.1

Disappearance of regular SECN pattern

1.2

Presence of irregular microvascular pattern (IMVP)

1.3

Presence of a demarcation line (DL)

2.

Undifferentiated (diffuse type) carcinoma

Loss of microvascular pattern (MVP)

Keywords

Early gastric cancerEndoscopic submucosal resection (ESD)GastritisMagnifying endoscopyStomachExplanation

Through magnified examination at the maximal magnifying ratio, using a magnifying endoscope with a spatial resolution of 7.9 μm, we were the first in the world to observe the microvascular architecture of early gastric cancers and report our findings [1, 2]. We published our preliminary findings in 2001 [2], and then in 2002 we performed a systematic study of the characteristics of the microvascular architecture in early gastric cancer, confining ourselves to non-ulcerated intramucosal cancers, reporting the following findings (Figs. 6.1 and 6.2) [1].

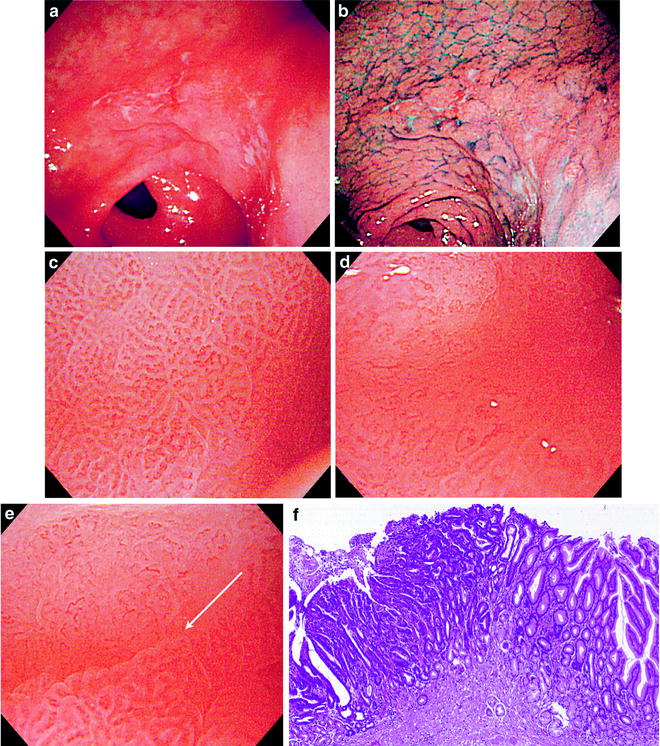

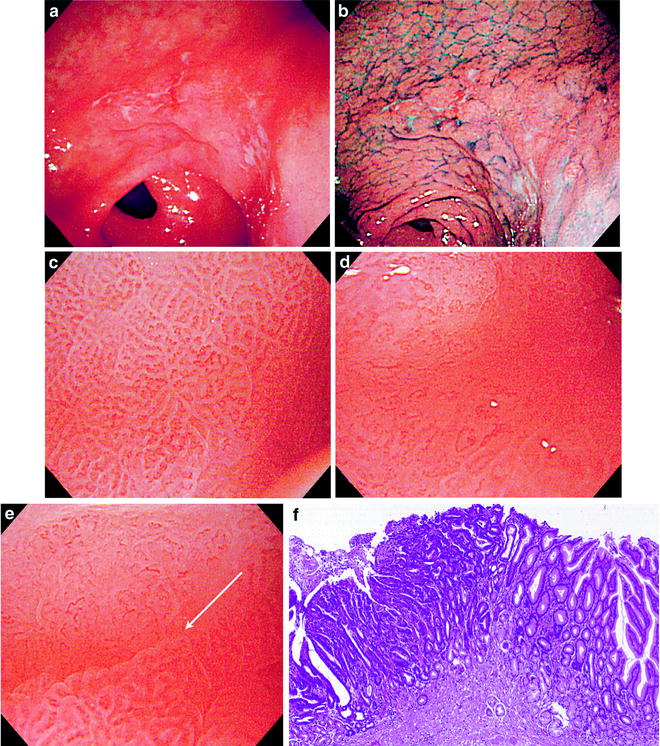

Fig. 6.1

(a–f) Differentiated (intestinal type) carcinoma (0 IIc, intramucosal cancer). (a) Non-magnifying endoscopic image. A faintly reddened depressed lesion with indistinct margins can be seen on the greater curvature of the gastric antrum. (b) Dye sprayed non-magnifying endoscopic image. Dye spraying reveals typical findings of early cancer with irregular margins. (c) Magnifying endoscopic image of the noncancerous background mucosa. We can see a regular SECN, with a symmetrical distribution and regular arrangement of homogenous small coil- and loop-shaped capillaries. (d) Magnifying endoscopic image of the cancer mucosa. We can see that the regular SECN has completely disappeared (disappearance of regular SECN pattern). There is a proliferation of dilated and tortuous microvessels with nonuniform and irregular morphology, from loops and branches to rings. Their distribution and arrangement is asymmetrical and irregular. This is an irregular microvascular pattern (IMVP). (e) Magnifying endoscopic image of the margin between the cancer and noncancerous mucosa. We can see a clear demarcation line (DL) due to the different microvascular architectures in the cancer mucosa and in the noncancerous mucosa. (f) Photomicrograph of histological section of the marginal area. This differentiated (intestinal type) carcinoma shows expansive growth as it develops, forming a distinct border with the surrounding background mucosa. The stroma, including proliferating vessels in association with the atypical irregular glands in this differentiated carcinoma, also shows a nonuniform morphology. (c–f) reprinted from [8] by permission of Gastrointest Endosc)

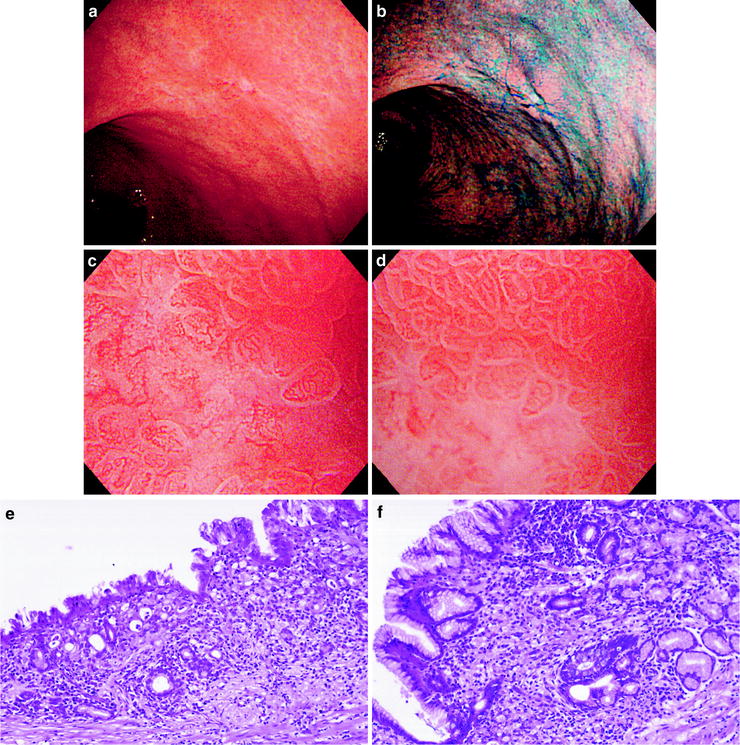

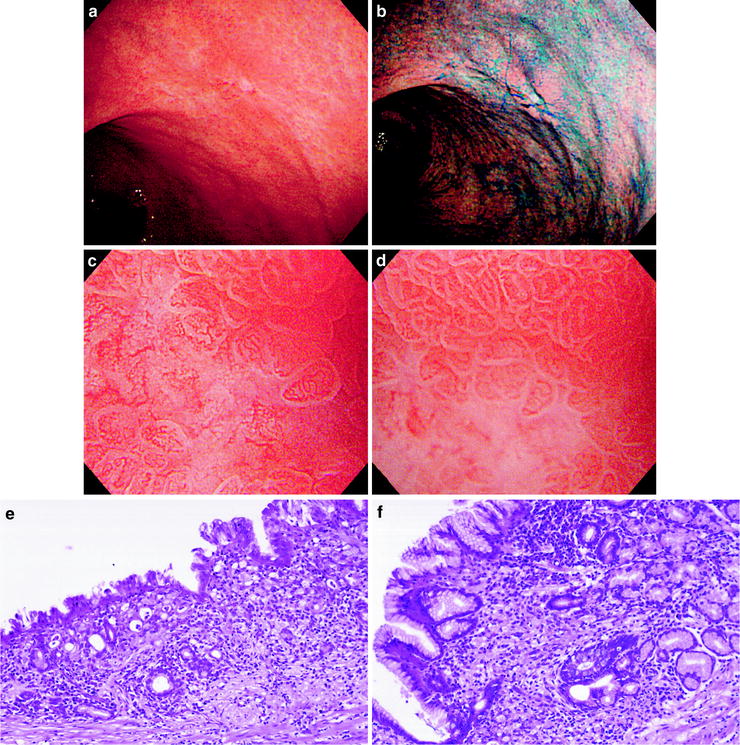

Fig. 6.2

(a–f) Undifferentiated (diffuse type) carcinoma (0 IIc, intramucosal cancer). (a) Non-magnifying endoscopic image. A pale depressed lesion with indistinct margins can be seen on the posterior wall of the gastric body. (b) Dye sprayed non-magnifying endoscopic image. With dye spraying, it is clearly a small depressed lesion, but the margins are unclear. (c) Magnifying endoscopic image of the same lesion where the depression and paleness are evident. We can see that the regular SECN pattern has disappeared (loss of MVP). (d) Magnifying endoscopic image of the marginal area of the same lesion. The margin is indistinct, with a gradual reduction in the vessel density from the regular SECN pattern of the background mucosa. (e) Photomicrograph of histological section corresponding to (c). This poorly differentiated signet ring cell carcinoma has infiltrated almost all layers. However, there is no stromal proliferation, and the mucosa is indented. These are the findings of the so-called cancerous atrophy. (f) Photomicrograph of histological section corresponding to (d). At the margin of the cancerous tissue, individual cancer cells have infiltrated sparsely and separately into the middle of the lamina propria. There is no associated proliferation of stromal tissue, including blood vessels. (c–f) reprinted from [8] by permission of Gastrointest Endosc)

A regular subepithelial capillary network (SECN) was seen in the background mucosa surrounding the cancer in all cases (Fig. 6.1c). However, the characteristics of the cancerous mucosa itself differed according to the degree of histological differentiation, in other words between differentiated and undifferentiated carcinomas.

6.1 Characteristics of the Microvascular Architecture in Early Gastric Cancer

6.1.1 Differentiated (Intestinal Type) Carcinoma (Fig. 6.1a–f)

In all cases of differentiated carcinoma, the surrounding regular SECN was absent, replaced by an irregular microvascular pattern (IMVP), characterized by proliferation of microvessels with nonuniform morphology, size, and arrangement within the cancerous mucosa (Fig. 6.1d). A clear demarcation line (DL) could be discerned due to the difference between the regular SECN in the noncancerous mucosa and the IMVP within the cancerous mucosa (Fig. 6.1e).

The microvascular architecture of differentiated carcinomas reflects the pathohistological features of the cancerous stroma (Fig. 6.1f).

More specifically, the IMVP is formed by proliferating tumor vessels in the cancerous stroma, and the disappearance of the regular SECN pattern and the presence of a clear DL are features that reflect the expansive and replacing growth pattern of differentiated carcinomas.

6.1.2 Undifferentiated (Diffuse Type) Carcinoma (Fig. 6.2a–f)

On the other hand, undifferentiated (diffuse type) carcinomas show reduction or loss of the regular SECN pattern seen in the background mucosa, i.e., loss of MVP (Fig. 6.2c, d). Histologically, unless a secondary factor such as erosion or ulceration is also present, the magnified endoscopic findings in undifferentiated carcinomas are of a reduction in the density of the regular SECN pattern. This is because the cancer cells show a histological growth pattern of proliferation invading the subepithelial layers and destroying the lamina propria, with no associated proliferation of stromal tissue, including blood vessels (Fig. 6.2e, f). Consequently, neither a distinct IMVP nor a clear DL is seen in undifferentiated carcinomas.

6.2 Clinical Applications of Magnifying Endoscopy (ME) Based on the Microvascular Architecture

The microvascular architecture of differentiated carcinomas is considered cancer-specific, making possible the following clinical applications:

I have previously reported the clinical usefulness of the following microvascular patterns characteristic of differentiated carcinomas:

1.

Disappearance of the regular SECN pattern (absence in the cancerous mucosa of the regular network of subepithelial capillaries seen in surrounding mucosa)

2.

Presence of an irregular microvascular pattern (IMVP—proliferation within the cancerous mucosa of microvessels with irregular sizes, morphology, and arrangement)

3.

Presence of a demarcation line (DL—a distinct border between the cancerous and noncancerous mucosa)

The general principle for the evaluation of irregularity in the microvascular architecture is to examine separately (1) the morphology of individual vessels and (2) their heterogeneity, distribution, and arrangement, and then make an overall evaluation.

6.3 Differential Diagnosis Between Cancer and Noncancer: Differentiating Between Focal Gastritis and IIb or Small IIc Lesions

Summary

Indications for ME in routine examinations: small flat or depressed reddened lesions detected on the gastric mucosa using non-magnifying endoscopy.

Diagnostic Marker—V: Microvascular Architecture

Differentiated carcinoma

1.

Disappearance of the regular SECN pattern

2.

Presence of a demarcation line (DL)

3.

Presence of an irregular microvascular pattern (IMVP)

Criteria for carcinoma

Positive for (1), (2), and (3)

Criteria for non-carcinoma

Negative for (1), (2), or (3)

Explanation

6.1 Background: Limitations of Non-magnifying Endoscopy

Before a method of magnified endoscopic detection of early gastric cancer was developed using the microvascular architecture as a diagnostic marker, the only way to diagnose superficial flat type 0 IIb early gastric cancers, or superficial depressed type 0 IIc minute gastric cancers, was to take multiple biopsies from flat mucosal areas showing localized color changes or subtle surface changes, e.g., redness or minute depressed lesions (erosions), and make the diagnosis on the basis of the pathohistological findings. In other words, it is difficult to distinguish between cancer and noncancer in flat reddened lesions and erosive gastritis-like lesions using non-magnifying endoscopy alone, so a multitude of unnecessary biopsies have been taken in everyday clinical practice [15].

6.2 A Prospective Clinical Trial, Its Clinical Significance, and Limitations

Since 2002 we have reported the usefulness of the microvascular patterns characteristic of differentiated carcinomas as a diagnostic marker in distinguishing between cancer and noncancer in flat reddened lesions and small depressed lesions [3–8]. We also demonstrated the usefulness of this method in a prospective clinical trial with large subject numbers (Tables 6.1 and 6.2) [9].

Table 6.1

The prevalence of magnified endoscopic findings in 158 flat reddened lesions (reprinted from [9] by permission of Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol)

Demarcation line | Disappearance of SECN | IMVP | |

|---|---|---|---|

Gastritis (95 % CI) | 25.3 % (18.6–32.8 %) | 22.9 % (16–29.8 %) | 0.7 % (0–2.1 %) |

Gastric cancer (95 % CI) | 100 % | 100 % | 92.9 % (79.4–100 %) |

Table 6.2

The diagnostic accuracy of each of the magnified endoscopic findings when making a diagnosis of gastric cancer (reprinted from [9] by permission of Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol)

Demarcation line ( %) | Disappearance of SECN ( %) | IMVP ( %) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Sensitivity | 100 | 100 | 92.9 |

Specificity | 74.3 | 77.1 | 99.3 |

PPV | 27.5 | 29.8 | 92.9 |

NPV | 100 | 100 | 99.3 |

Overall accuracy | 76.6 | 79.1 | 98.7 |

As can be seen in Table 6.2, two points of clinical significance can be identified from this trial.

The first point is the 100 % negative predictive value for DL. In other words, if we detect a flat reddened lesion with non-magnifying endoscopy, proceed to a magnified endoscopic examination, and cannot see a DL, we can 100 % rule out a cancer. Similarly, the NPV for disappearance of the regular SECN pattern is 100 %. In other words, if the same SECN is seen within the lesion continuous with the surrounding mucosa, we can rule out cancer with 100 % certainty.

Based on these findings, the prospect of avoiding unnecessary biopsies presently being taken in countless numbers in general clinical practice is of great clinical and medical economic significance.

The second point is the high diagnostic accuracy of 98.7 % for IMVP. If an IMVP is seen, cancer should be suspected with a high probability.

However, this high diagnostic accuracy cannot be considered enough evidence to make the diagnosis of cancer without performing any biopsies.

The reasons for this are that we only detected 14 cancers in our study, and it involved a single center and a single endoscopist (myself). In other words, further studies are required to demonstrate reproducibility. We await the results of a multicenter prospective randomized trial currently in progress.

6.4 Pointers for Examinations and Differential Diagnoses in Screening of Small Lesions Using ME

6.4.1 Which Lesions Should Be Magnified and When

First, we examine the entire stomach, every nook and cranny, using non-magnifying endoscopy, and decide which lesions to target.

Previously, when I detected a lesion, I immediately switched from non-magnifying to magnifying endoscopy, but I changed to a system whereby I finish the non-magnifying examination before starting the magnified examination. The reasons were as follows: (1) for the same reason that biopsies are taken from the lesions most suspicious for cancer on non-magnifying endoscopy, magnified examination should be performed on those lesions for which differentiation from cancer is most necessary at the end of the procedure. (2) Unlike the large bowel, it is easier to reapproach suspicious lesions following non-magnifying examination of the entire stomach. (3) If we immediately switch over to magnifying endoscopy and make frequent use of the technique, outlined in Chap. 2, of aspirating air from the stomach, we tend to prolong the examination more than necessary due to induction of peristalsis, the necessity for repeated reinsufflation and aspiration, and the possible interference with observation of other parts of the stomach.

This is the same in principle as “Decide which lesions to biopsy after completion of the non-magnifying examination.”

6.4.2 Draw Close and Immediately Increase the Magnifying Ratio

After taking several non-magnifying images, we use the technique described in Chap. 2, drawing as close to the lesion as possible, press down on the zoom lever on the control section to provide the maximal magnifying ratio, and apply the tip of the hood closely to the mucosa.

6.4.3 Algorithm for Evaluation of the Microvascular Architecture

The general principle for magnified endoscopic examinations of the stomach is to use the nonlesion mucosa as the control. Accordingly, we examine and photograph the marginal area and then examine, photograph, and identify the internal microvascular architecture of the lesion. In practice, I use the following algorithm to evaluate the microvascular architecture:

1.

First, ascertain the characteristics of the surrounding regular SECN pattern.

2.

Does the surrounding regular SECN pattern disappear at the margin?

3.

Is there a clear DL where the regular SECN pattern disappears?

4.

Do the vessels within the lesion have the same regular SECN pattern as the surrounds?

5.

If it is different, is it an IMVP?

6.4.4 How to Get the Focus Right at Maximal Magnification

After closely applying the tip of the hood, if a slight separation prevents the mucosa coming into focus, apply slight suction to draw the mucosa closer to the scope tip. Conversely, if the mucosa is too close to focus properly, insufflate a small amount of air to remove the mucosa from inside the hood. It is important to develop this technique of maneuvering the mucosa by tiny increments in and out of the hood, and take a photograph at the instant the mucosa comes into focus.

6.4.5 When Aortic Pulsations and Respirations Interfere with Observation

When forceful movements of the stomach wall associated with peristalsis, aortic pulsations, and respiration, for example, in the greater curvature of the gastric body, evaluations can be made from still images. When evaluations are still difficult using the endoscope monitor, we sometimes reevaluate the images after the procedure (although this is impractical considering the reality of these procedures).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree