Clinical appropriateness

Organizational appropriateness

Benefits overcome risks

Provide procedures really useful individually

Endoscopic follow-up

Appropriateness = why and who

Methodology = when and how

3.2 Indications to the Follow-Up in Digestive Endoscopy

The indication to perform an endoscopic follow-up examination is acceptable when decided by the physician on the basis of strong evidence of clinical utility (i.e., effectiveness). Any follow-up endoscopy required only for physician’s personal serenity, to stay on the safe side in a concept of “defensive medicine,” is unacceptable and inappropriate. Nonetheless, it may happen that the patient asks for a possibly inappropriate surveillance endoscopy: in such cases, the request should not be rejected a priori, it should rather be judged carefully on individual basis, considering the potential for reassurance and its important psychological impact. Nowadays, many scientific societies consider appropriate an endoscopic examination performed to reassure those particularly anxious subjects, whose distress about health status cannot be completely quietened by verbal reassurance of the specialists.

3.3 Why an Endoscopic Follow-Up Examination?

When assessing the rationale of an endoscopic surveillance examination, it is mandatory to ask oneself whether the condition or disease deserves any surveillance. Such judgment inevitably arises from the presence of scientific evidence of clinical utility, from the knowledge of the natural history of the disease, as well as from the epidemiological relevance of the expected event that is under surveillance.

Establishing if these criteria can always be satisfied is not an easy task. As a general rule, endoscopic follow-up of benign conditions is considered appropriate only within the framework of clinical studies. On the reverse, such criteria are fully satisfied for post-polypectomy surveillance: there is, in fact, compelling evidence of its clinical utility [1]; the natural history of colonic carcinogenesis (through the adenoma–carcinoma sequence or the serrated pathway) is recognized and because the incidence of colorectal cancer is high.

The same does not hold true for Barrett’s esophagus, where evidence of clinical utility is weak, natural history of the condition is still poorly understood, and the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has long been overestimated due to the poor quality of the studies, often underpowered [2–5]. Even less known is the natural history of Barrett’s dysplasia; also, ablative therapies such as radiofrequency ablation will likely modify the cost–utility and cost-effectiveness of surveillance in the future, leading to a paradigm shift in the need for surveillance of these patients [6–11].

As mentioned, the question about why perform endoscopic follow-up does not always have a clear, explicit, and definitive answer: conditions that today are kept under surveillance may in the future be not as the progress in medicine removes the grey shadows from our knowledge.

3.4 Who Should Be Surveilled?

Once established that the condition actually deserves surveillance, the other key question is the selection of candidates , i.e., which patient affected with a given risk condition should be really kept under surveillance?

Such judgment can be drawn by an accurate assessment of the individual risk profile, including age, comorbidities, and capacity of the subject to sustain the therapeutic intervention(s) driven by a positive follow-up examination. Practically speaking, if the patient is too old or frail to resist surgery, is there any sense in surveillance for colorectal cancer recurrence? Progress in endoscopic techniques of ablation or resection of early gastrointestinal neoplasia, may transform patients “unfit for surgery” into good candidates for mini-invasive forms of treatment.

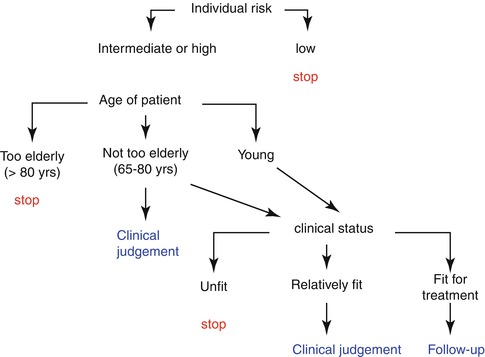

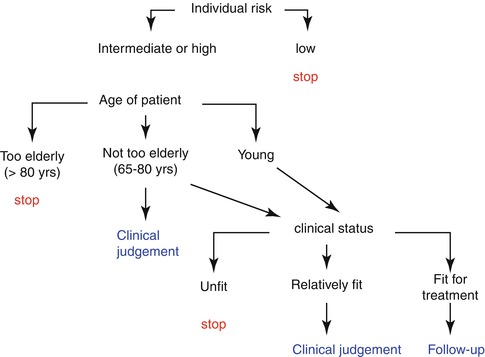

A possible algorithm is depicted in Fig. 3.1, which takes into account patient’s risk profile, age, and comorbid conditions as decision knots or filters to pass judgment on the appropriateness of an endoscopic follow-up.

Fig. 3.1

Decision tree or algorithm on the appropriateness of endoscopic surveillance on patients with diseases deserving follow-up

3.5 How to Perform Surveillance?

As for the methodology of the endoscopic follow-up, the seminal importance of the operator and the facility is intuitive. Technical competence together with adequate technology equipment are crucial factors for the safety and efficacy of follow-up endoscopy, minimizing potential complications while in the meantime maximizing potential benefits deriving from an early intervention.

Besides, follow-up endoscopy should be modulated to the needs of individual case. Such a modularity of follow-up (patient-tailored) entails that the surveillance protocol can be deviated or rerouted according to the incidence or identification of lesions (e.g., high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus or dysplasia-associated lesion or mass in patients with ulcerative colitis) that require either an increased level of complexity of the follow-up, with need for referral to tertiary centers more equipped in terms of technology or manpower, or a modification of surveillance intervals.

In particular, technical competence expresses the level of application of scientific knowledge, professional abilities, and available technology to improve health conditions. The competency of those who perform the endoscopy and those who draw the histology report that influences all the subsequent decisional chain is by no way a secondary aspect. This represents a big problem at all latitudes: ability to match up with the situation should never be taken for granted.

A major aspect in terms of operator’s competence for surveillance endoscopy is the diagnostic accuracy and particularly its negative, i.e., the rate of missed diagnosis of pre-neoplastic or neoplastic lesions (missing rate). Any cancer detected within 3 years of a previous “negative” colonoscopy is termed “interval” cancer and should be considered as a missed lesion [12–18]. The missing rate is not a trivial problem: also, in expert hands, it can be as high as 25 % for small or flat adenomas [19–21] and can reach up to 7 % for overt cancers [15–17]. While the missing rate may not heavily impact efficacy of screening endoscopy, where majority of patients are healthy and does not have cancer, it is potentially devastating in the field of surveillance, which, in turn, is directed toward subgroups of patients at risk of having or developing cancer.

The critical question: is this exam really negative? It urges that everyone performing a surveillance colonoscopy knows and applies those techniques allowing for an accurate evaluation of bowel mucosa during apparently negative examinations (chromoendoscopy, magnification, light technology, etc.) [22, 23]. Such competency requires formal and adequate training and continuous updating (maintenance curve), possibly periodically audited or assessed by external independent subjects (credentialing) and that is when things begin to get difficult.

Health systems often taken as an example in terms of quality have made tremendous efforts to improve patients’ outcomes through systematic quality improvement programs. In UK, screening colonoscopists have improved their overall cecal intubation rate from less than 60 % in 2006 [24] to over 90 % in 2011 [25] thanks to a nationwide training and retraining process of all those involved in CRC screening. Improving colonoscopic skills and bowel preparation may also decrease nonadherence to the recommended post-polypectomy surveillance interval. Inadequate training and absence of retraining inevitably lead to insufficient endoscopic practice not up to the high-quality standards often required by an accurate follow-up.

3.6 When to Perform Surveillance?

Last but not least there is the issue of when to perform surveillance, that is, the appropriate timing of endoscopic follow-up start up and the optimal interval between examinations. Such information, at best, can be derived by specific guidelines on the disease, when available [26, 27]. The personal clinical practice should then be tailored accordingly.

As a paradigmatic example, follow-up after curative surgery for colorectal cancer remains controversial, with no consensus on a protocol. Its evolution has largely lacked an evidence base. Current guidelines from the UK, the USA, Europe, and Canada all have differing recommended schedules for clinic visits, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels, colonoscopy, and abdominal and chest imaging [28]. However, there is a global lack of consistency. Standardized follow-up regimens need to be developed. Many institutions continue to have their own follow-up regimen. As life expectancy increases, with a reduction in all-cause mortality and spiralling costs of sophisticated imaging modalities, intensive follow-up regimens are becoming more expensive. The cost-effectiveness and cost benefit of such regimens are still unevaluated. The economic burden of this unsystematic follow-up is immense.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree