Background

Approximately 10% of men with newly diagnosed prostate cancer present with metastases. In addition, 3–41% of patients with localized (T1–T2) and 12–55% with locally advanced prostate cancer (T3–T4) fail primary therapies and develop metastatic disease at 10 years [1]. When prostate cancer has progressed to this advanced stage, it is incurable. Deaths per year from metastatic prostate cancer are estimated to be 204,000 globally and account for 4–15% of all cancer-related deaths, depending on the proportion of elderly men in the population [2–4].

The main site of metastatic disease is bone and autopsy studies have indicated that 85–100% of men who die of prostate cancer have bone metastases [1]. Factors that are associated with an increased risk of developing metastatic disease include clinical stage, Gleason score > 8, and a pre-therapy PSA of > 20 ng/mL. These factors may allow stratification of patients for treatment selection.

The standard first-line therapy for symptomatic metastatic prostate cancer is androgen suppression therapy which has a response rate of about 85%. Patients who fail first-line therapy may benefit from androgen withdrawal with response rates of 30–40% and duration of about 6 months. Second-line hormone manipulation may also be used but nearly all patients will eventually become refractory to androgen deprivation therapy. At this stage, treatment options are palliative and include chemotherapy, external beam radiotherapy, bisphosphonates and radio-isotopes.

This chapter will present evidence on some of the major issues regarding the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer.

Medline, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library were searched for randomized studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of treatment interventions in metastatic prostate cancer. Databases were searched from 1966 to 2008 with no language restrictions.

Clinical question 30.1

What is the most effective timing of hormone therapy: immediate or deferred?

The evidence

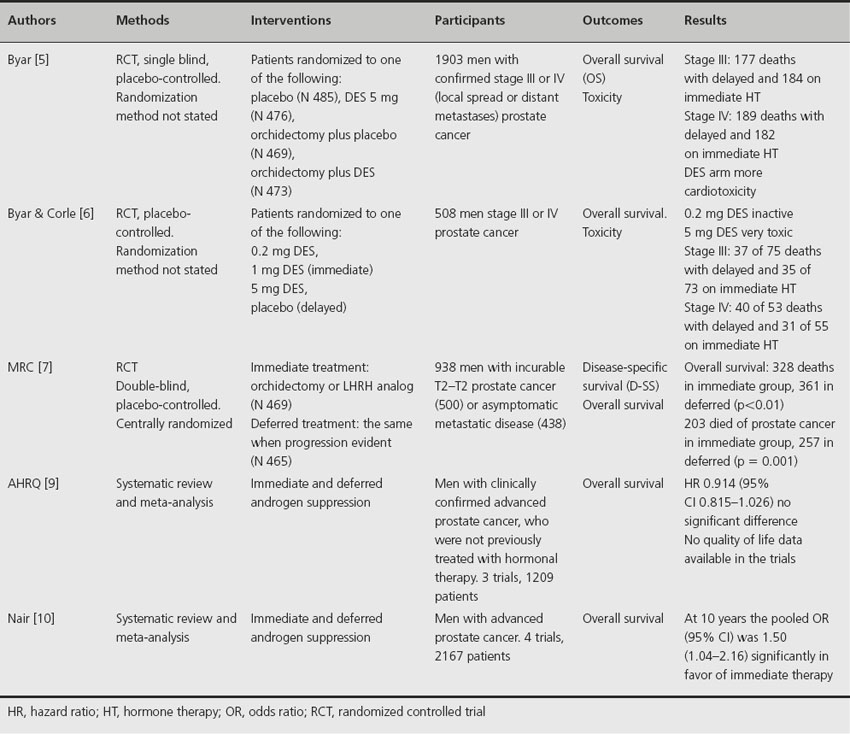

Androgen suppression is effective in delaying tumor progression in men with prostate cancer. In patients with locally advanced or asymptomatic metastatic prostate cancer, controversy exists concerning the ideal time to initiate hormone therapy. Patients with symptomatic disease should be treated immediately, but for asymptomatic disease the situation is less clear. Due to the protracted course of well-differentiated prostate cancer, many men with asymptomatic disease may die of other causes before disease progression requires intervention, and treating such patients with immediate hormone therapy would expose them to unnecessary treatment-related side-effects such as gynecomastia, cardiotoxicity, osteoporosis, and erectile impotence. In addition, early hormone therapy could theoretically select for androgen-independent cells and prematurely develop a condition which has no viable treatment options. However, early androgen suppression may be more effective when the tumor burden is low and may delay the development of serious complications. Alternatively, delaying hormone treatment could provide an effective treatment when disease progression occurs rather than being palliative to asymptomatic disease. A number of randomized trials have compared the clinical value of giving immediate or delayed androgen deprivation therapy in patients with advanced prostate cancer (Table 30.1).

Table 30.1 Randomized trials and meta-analyses of immediate versus delayed hormone therapy in metastatic prostate cancer

Between 1960 and 1975, the Veterans Administration Co-operative Urological Research Group (VACURG) conducted a series of randomized trials of various treatments for patients with newly diagnosed prostate cancer [5,6]. In these studies, men with advanced prostate cancer were randomized to various doses of diethylstilbestrol (DES) or to placebo. Those patients in the placebo group received hormone therapy when the disease had progressed, and can thus be considered as receiving deferred hormone therapy. In one trial there was no significant difference in overall survival between immediate or deferred treatment although only 44% of patients assigned to placebo progressed and actually had their treatment changed. However, a separate study indicated that immediate androgen deprivation (DES 1 mg), beginning at diagnosis, increased overall survival in stages III and IV compared to deferred treatment. However, no statistical p values were reported.

Another study by the Medical Research Council trial randomized 934 men with histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the prostate to receive either immediate (N 469) or deferred (N 465) androgen deprivation hormone therapy [7]. Patients had either local disease considered too far advanced for curative treatment (T2–T4) or asymptomatic metastatic disease and a life expectancy of 12 months or more. Hormone therapy either commenced immediately at the time of diagnosis or was deferred until the disease had progressed sufficiently to warrant clinical intervention. A significant improvement in overall survival was reported for immediate treatment when all patient groups were pooled. However, when individual groups were analyzed, only men with nonmetastatic disease had a significant improvement in overall survival. In men with metastatic disease at randomization, there was no significant difference in survival between the two arms. Overall, significantly more men receiving deferred hormone therapy developed complications. A more recent review of the data after a longer follow-up indicates that there is no significant difference in overall survival between patients treated immediately and those receiving deferred hormone therapy [8].

A meta-analysis of the three trials discussed above [9] utilized a random effect model that reduced to a fixed effect model when the studies were homogeneous. The combined hazard ratio (95% confidence interval (CI)) was 0.91 (0.815–1.026) where a ratio of less than 1 indicates that immediate therapy is superior, although statistical significant was not reached. A second meta-analysis published by the Cochrane Library [10] included an additional study of immediate versus deferred therapy after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenopathy in men with node-positive prostate cancer [11]. This analysis concluded that early androgen suppression may provide a small but statistically significant improvement in overall survival at 10 years.

Comment

Although only one trial of men with metastatic prostate cancer documented an improvement in overall survival with immediate treatment (VACURG II), another study reported a reduced rate of severe complications when hormone therapy is given early (MRC). These findings tend to support the use of immediate androgen suppression therapy in metastatic prostate cancer. Evidence and recommendation Grade 1B.

Clinical question 30.2

Do data on nonsteroidal antiandrogens support the use of combined androgen blockage?

The evidence

Androgen suppression (AS), either by orchidectomy or medical castration with a luteinizing-hormone releasing-hormone (LHRH) agonist, is the standard first-line treatment for advanced prostate cancer. This treatment reduces circulating testicular-derived testosterone, thereby minimizing androgen-induced growth stimulation of prostate tumors. However, residual testosterone, secreted by the adrenal glands, may still induce some stimulatory activity on prostate tumor growth. This can be theoretically overcome by blocking androgen receptors in the tumor using antiandrogens. This combined therapeutic approach of using androgen suppression and antiandrogens is termed combined androgen blockage (CAB) or maximum androgen blockage (MAB). Antiandrogens may be steroidal in structure, such as cyproterone actetate, or nonsteroidal, such as nilutamide or flutamide. Both these classes of antiandrogens have been incorporated into randomized trials comparing the efficacy of CAB with AS. It is clinically important to determine whether one class of antiandrogens is superior when used in a CAB regime.

There have been no randomized trials comparing CAB using a nonsteroidal antiandrogen with CAB using a steroidal antiandrogen. However, a large meta-analysis undertaken by the Prostate Cancer Trialists Collaborative Group compared 27 randomized trials of CAB versus AS and provided a separate analysis of trials incorporating nonsteroidal and steroidal antiandrogens [12].

Individual patient data were collected from the 27 trials and included information on stage, age, assigned treatment, last follow-up, date of death and cause of death. In the CAB regimes orichidectomy or an LHRH agonist was combined with nilitamide in eight trials, flutamide in 12 trials and cyproterone acetate in seven trials, with a total number of patients of 8275. At the end of the study 72% of men had died, of whom 80% had died of prostate cancer. The pooled analysis indicated a 5-year overall survival rate of 25.4% for CAB and 23.6% for AS alone, which was not statistically significant (p = 0.11). When a subgroup analysis was preformed, cyproterone acetate studies, which contributed 20% of the evidence, favored AS alone, with 5-year overall survival rates of 15.4% for CAB and 18.1% for AS (p = 0.04). However, the studies using the nonsteroidal antiandrogens in the CAB regime were significantly in favor of CAB, with 5-year overall survival rates of 27.4% for CAB and 24.7% for AS alone (p = 0.005).

Comment

The evidence suggests that the administration of CAB using nonsteroidal antiandrogens appears to be superior in terms of overall survival compared to the use of steroidal antiandrogens. However, the absolute difference in 5-year overall survival rates between CAB when using nonsteroidal antiandrogens and AS is only 2.9%. Evidence and recommendation Grade 2B.

Clinical question 30.3

Does intermittent androgen deprivation therapy reduce the side effects compared to continuous treatment?

The evidence

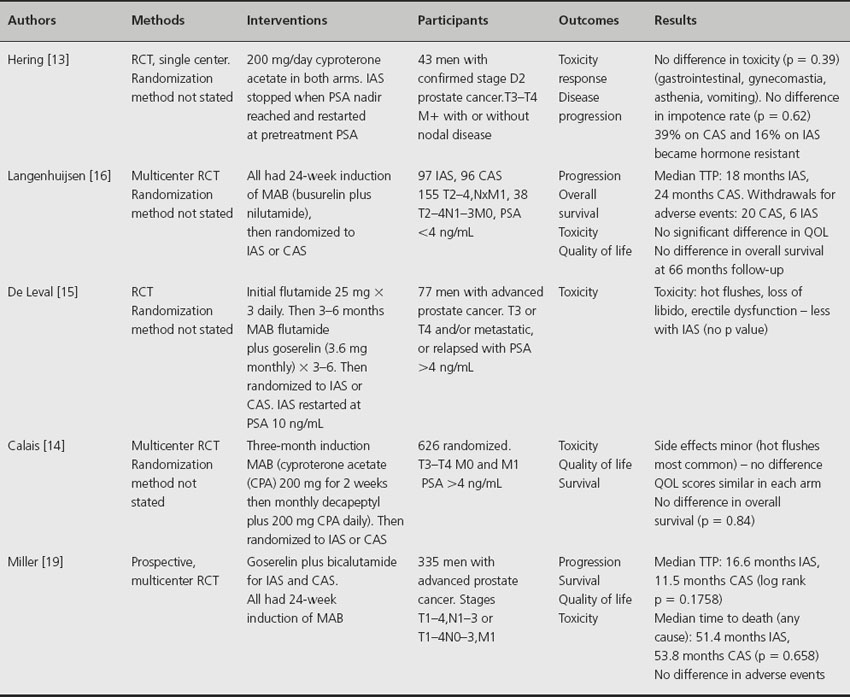

Continuous androgen suppression (CAS) produces excellent short-term results for advanced prostate cancer but the long-term outcome is limited by treatment-related side effects and the development of disease unresponsive to androgen manipulation. Intermittent androgen suppression (IAS) may inhibit metabolic pathways associated with the onset of androgen-independent disease and is a relatively recent area of research. With IAS, patients are treated with androgen deprivation for a period of time until a clinical or biochemical response is achieved, at which point the treatment is stopped. Active monitoring is continued until there is evidence of disease progression, when androgen deprivation therapy is started again and this cycle is repeated. The major aims of IAS are to maintain androgen responsiveness and to reduce the toxicity associated with continuous hormone therapy, in particular restoration of sexual function between treatment cycles.

Five randomized trials have compared IAS with CAS in patients with metastatic prostate cancer (Table 30.2). One small study reported that fewer patients developed hormone resistance when receiving IAS compared to CAS (10% versus 38%) [13]. Potency was maintained in 96% of men during the intervals between IAS cycles and post treatment in 40% on IAS and 25% on CAS [14]. Three studies reported no difference in toxicities between patients groups although one observed the frequency of hot flushes, loss of libido and erectile function was less with IAS [15]. Quality of life was improved with IAS in one study [13] and similar in both arms in two trials [14,16]. There was no significant improvement in overall survival [14,16].

Table 30.2 Randomized trials comparing intermittent versus continuous hormone therapy in metastatic prostate cancer

A systematic review of these four studies, plus an additional randomized trial on men with nonmetastatic disease but locally advanced prostate cancer [17], concluded that IAS has a slightly reduced adverse event rate compared to CAS and appears more favouable in controlling impotence [18].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree