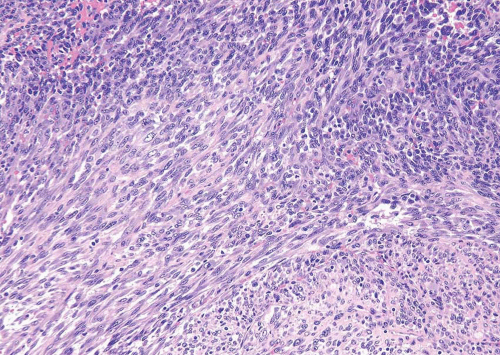

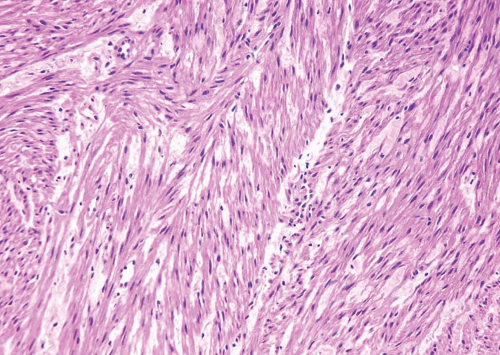

cases will demonstrate tumor necrosis and mitotic activity of 10 per 10 hpf or more. Although most smooth muscle tumors of the bladder are overtly either benign or malignant, there are some tumors with low cellularity yet with atypia. In the uterus, these lesions would be classified as benign, even if accompanied by readily identifiable mitotic figures. As there is no follow-up data in the literature for comparable lesions in the bladder, it may be more prudent to designate these lesions as “atypical smooth muscle tumors” describing their findings and stating that their biological behavior is unknown. For those lesions without mitotic figures, it can be added that it is likely that they will behave in an indolent fashion.

FIGURE 11.2 Leiomyoma (higher magnification of Figure 11.1). |

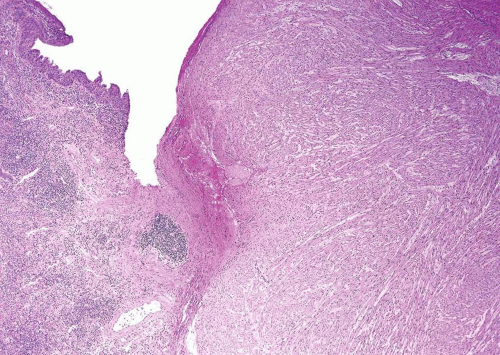

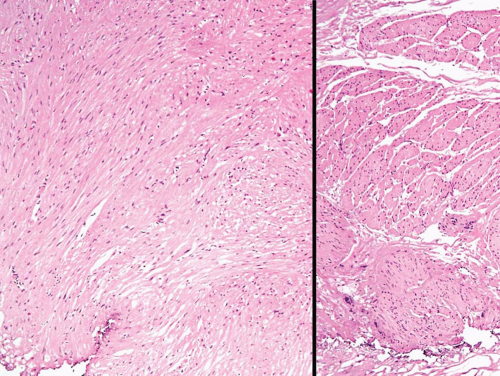

FIGURE 11.3 Leiomyoma composed of irregular sheets of smooth muscle (left) as opposed to well-formed discrete smooth muscle bundles of normal muscular propria (right). |

cells that may express smooth muscle markers by immunohistochemistry but are of myofibroblastic origin (see below). Over two thirds of LMS will demonstrate immunoreactivity of both smooth muscle actin (1A4) and muscle-specific actin (HHF-35). Desmin will be positive in less than 50% of cases whereas epithelial membrane antigen is usually negative. Up to 50% of LMS may be immunoreactive for cytokeratins although focal (13). It has been suggested that caldesmon will be positive in LMS but negative in myofibroblastic lesions (14) (Table 11.1).

TABLE 11.1 Spindle Cell Neoplasms of the Bladder: Immunoreactivity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

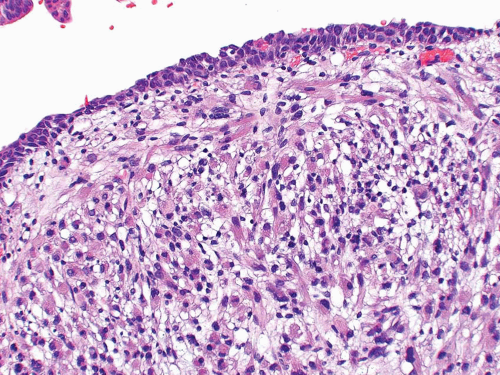

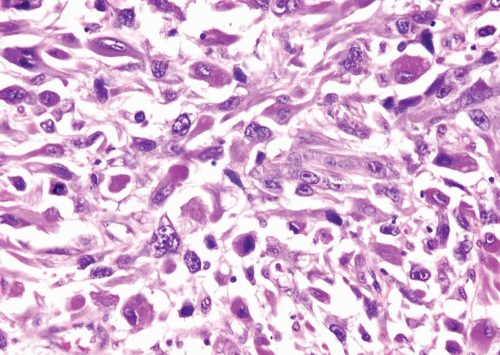

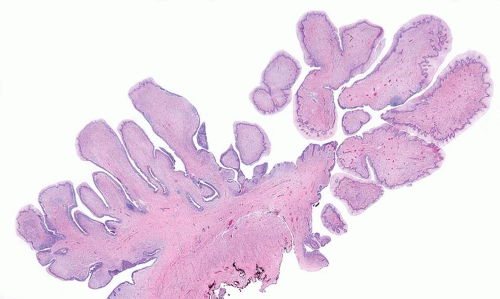

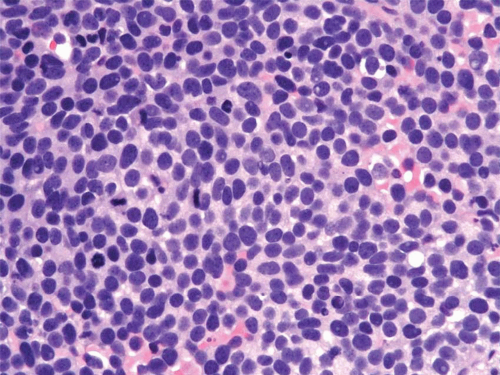

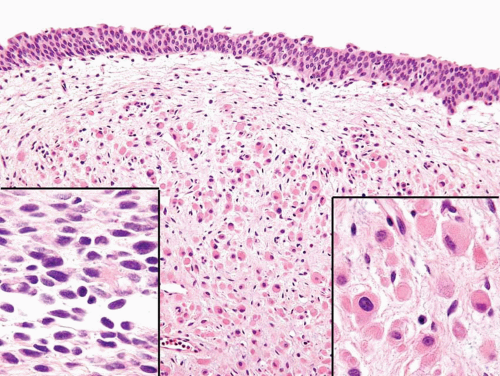

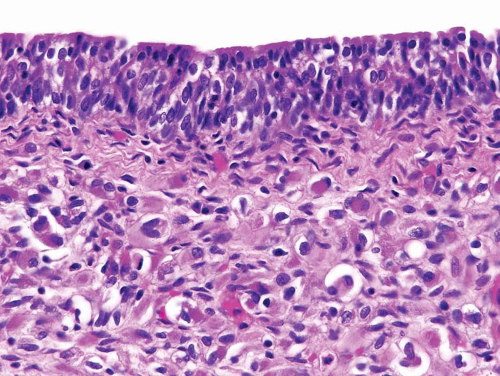

condensation of tumor cells, including strap cells and rhabdomyoblasts, located immediately beneath the urothelium (Figs. 11.7, 11.8). The underlying stroma is hypocellular and myxoid. In other polypoid tumors, the neoplastic cells are diffusely distributed throughout. A significant percentage of vesical RMS does not have an exophytic component and in these the tumor cells infiltrate the bladder wall diffusely (18). The spindle cell and alveolar variants of RMS may be rarely encountered. Typical rhabdomyoblasts and cross striations are seen frequently in exophytic RMS but rarely

seen in the spindle cell and alveolar types. Rare cases of vesical RMS have been described in adults and these may have embryonal, pleomorphic, or alveolar patterns (17). RMS should enter in the differential diagnosis of all spindle and myxoid lesions of the genitourinary tract in the pediatric age group. Tumor cells will be at least focally immunoreactive for desmin and myogenin, the latter in a nuclear distribution. Immunoreactivity for myoglobin is also diagnostic although it is positive in a minority of cases (Table 11.1).

although cytokeratin, myoD1, myogenin, and desmin should help confirm the diagnosis (19).

FIGURE 11.8 Cambium layer of botryoid variant of rhabdomyosarcoma (higher magnification of Figure 11.7). |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree