An office evaluation of men’s health in primary care requires a thorough understanding of the implications of male sexual dysfunctions, hypogonadism, and cardiometabolic risk stratification and aggressive risk management. The paradigm of the men’s health office visit in primary care is the recognition and assessment of male sexual dysfunction, specifically erectile dysfunction, and its value as a signal of overall cardiometabolic health, including the emerging evidence linking low testosterone and the metabolic syndrome. Indeed, erectile dysfunction may now be thought of as a harbinger of cardiovascular clinical events and other systemic vascular diseases in some men.

Why men’s health?

Gender-based medicine, specifically recognizing the differences in the health of men and women, drew much attention in the 1990s. The National Institutes of Health’s Office of Research on Women’s Health was established in 1990, and in 1994 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) created an Office of Women’s Health, resulting in a dramatic increase in the quantity and quality of research devoted to examining numerous aspects of women’s health such that today women’s health research is clearly mainstream.

While decades of research have yielded many important findings about health and disease in men, this knowledge has not resulted in the benefits expected. Men are still less likely than women to seek medical care, and are nearly half as likely as women to pursue preventive health visits or undergo screening tests. Recent data indicate that 68.6% of men aged 20 years and older are overweight, and life expectancy of men continues to trail that of women, by 5.3 years in 2003.

Men’s Health as a concept and discipline is in a historic state compared with women’s health. Most clinicians and the public consider Men’s Health to be a field concerned only with the prostate and sexual function. Men’s health has recently become a hot topic in these specific areas with large amounts of dollars being spent on remedies for prostate health, improved urinary flow, and enhanced erections, with a smaller amount directed to overall improved health.

Men do not use or react to health services in the same way as women. Men are less likely to go to health care providers for preventive health care visits. Men are also less likely to follow medical regimens, and are less likely to achieve control with long-term therapeutic treatments. The Commonwealth Fund did a mass survey and found that “an alarming proportion of American men have only limited contact with physicians and the health care system generally. Many men fail to get routine check-ups, preventive care, or health counseling and they often ignore symptoms or delay seeking medical attention when sick or in pain.” This report concludes by noting the need for increased efforts to address the special needs of men as well as attitudes toward health care. Men are more likely to be motivated to visit the doctor for diseases that specifically affect men most, such as baldness, sports injuries, or erectile dysfunction (ED). The presentation of a man to the clinician’s office with a sexual health complaint can present an opportunity for a more complete evaluation, most notably with the complaint of ED. In a landmark article published in December, 2005, Thompson and colleagues confirmed what had been long believed: that ED is a sentinel marker and risk factor for future cardiovascular events. After adjustment, incident ED occurring in the 4300 men without ED at study entry enrolled in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) was associated with a hazard ratio of 1.25 for subsequent cardiovascular events during the 9-year study follow-up (1994–2003). For men with either incident or prevalent ED, the hazard ratio was 1.45. Thus, men with ED are at risk for developing cardiac events over the next 10 years, with ED as strong a risk factor as current smoking or premature family history of cardiac disease. Never before has the association of ED or a male sexual dysfunction been so strongly linked as a harbinger of cardiovascular clinical events in men.

Who is the Men’s Health doctor: primary care physician versus primary care physician Men’s Health subspecialist versus urologist

While urologists are typically thought of as men’s doctors as obstetricians/gynecologists are considered women’s doctors , the issue remains as to who is to shoulder this responsibility in the decades to come, regardless of reform. Will it be a shared care approach, including clear communication between urologists and primary care clinicians, and vice versa, or do we need to enhance this relationship or specialty? Do we need to create separate “Centers of Excellence” for men’s health, as the author has strived to do at the Miriam Hospital and Warren Alpert School of Medicine of Brown University? Do we need to establish Men’s Health Fellowships for nonurologists dealing more with the issues of “medical urology?” Having practiced as a primary care clinician for over 25 years before opening this Center of Men’s Health 2 years ago (composed of urological, psychological, and comprehensive cardiometabolic medical evaluation), I (the author of this article) feel a need to reflect on past and present experience.

First, what I miss most from routine primary care is longitudinal care compressed into a series of vignettes, no greater than 10 to 15 minutes, spanning the course of decades. There is a sense of familiarity and rapport that is immediate and refreshed in each visit. The patient’s concerns are varied, often multiple and unpredictable, and require rapid thinking, concise summations, and treatment plans. I came to treasure these encounters, and felt validated and loved by my patients.

Second, I have struggled to morph myself into a subspecialist from a primary care clinician. In my former life, I dictated or charted solely for myself and my cross-covering peers, and not for review as a referring subspecialist. With this additional role, my language must be supportive, direct, and nonprovocative. I must recognize the boundaries of my work, make recommendations, but recognize that as one primary care provider/subspecialist speaking to another, the tone and content of my charting has to focus almost entirely on evidence-based medicine, noting the studies rationalizing my suggesting the use of an angiotensin receptor blocker/angiotensin-converting enzyme for this patient’s hypertension and sexual function, or the addition of bupropion to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. I must take caution to recommend a slow taper of the noncardioselective β-blocker in the post–myocardial infarction patient, now 3 years out, and replacement with perhaps a more sexually friendly and endothelial enhancing drug such as nebivolol. When I suggest a means to improve diabetic control, including focus on lifestyle and diet, or perhaps a more aggressive stance to managing dyslipidemia, I must proceed with caution. Who am I and what training do I have to make these recommendations? Most internists to whom I correspond do not know of the years spent at American Urological Association (AUA) meetings, boards, committees, and self-developed preceptorships I have encountered. Nor do they know of the tumultuous path to election to the Sexual Medicine Society of North America’s fellowship and Board of Directors, and membership to the AUA’s Committee on Men’s Health. To them, I can easily be accused of assuming primary care for the patient. And indeed, there may be some accuracy to this claim in the post–radical prostatectomy “penile-rehab” patient when I am aggressively suggesting control of cardiometabolic risk factors and neuromodulation with statins, to name examples. It is clear that without the background knowledge, the primary care clinician may misinterpret my goals and rationale.

Therefore, not to be accused of “co-opting” primary care patients from one clinician to another, I must presently recognize when it is time to step aside, relinquish my duties and contact with patients with whom I have become quite fond of over the past 2 years during their rehabilitation, and steadfastly refuse overtures to become their primary care physician. My appeal may be that I am focusing on a single, highly personal medical problem, their sexual dysfunction, and not the usual laundry-list of the standard primary care visit: type 2 diabetes; hypertension; dyslipidemia; sprinkled with a bit of generalized anxiety.

Our interactions in the Men’s Health Center are not replicated in the world of volume primary care, and I am the first to acknowledge the wondrous reality of my situation and its accompanying depth of interaction and emotional content. Indeed, my focus is often as much “lifestyle coach” as it is cardiometabolic medicine.

Which system is better? This is yet to be known. In my former life as primary care physician whereby I incorporated this interest of sexual medicine into my daily practice, I saw on average 34 to 36 patients per day, short-changing much thought and discussion to remain respectful of patients’ (and my) time, yet bringing sessions to a close with a warm touch of the arm or shoulder, and some genuine laughter. Contrast this to the Men’s Health Center, where each patient has a similar “template” and complaints are relatively a known quantity, as are patients’ stories. Though I approach the second with passion, excitement, and “reflective listening,” maintaining eye contact, we may not know the answer to this question until we have objective outcomes. However, intuitively I feel that this combination of urologist-andrologist/internal medicine-family physician/psychologist-sex therapist is most unusual and offers a unique opportunity to enhance gender-specific care. Routinely individuals see two providers at the initial visit: urologist/internist or internist/psychologist. I am kidded by the urologists; my notes still begin with a story: married, divorced, or living with wife and children; partnered or semi-partnered; open-married or close-married; job satisfaction; life stresses; and partner relationship. Again, the good in this model is my focus on the “whole” male.

Historically, the office visit for a man complaining of sexual dysfunction focused solely on ED, and this was the narrow definition of men’s health. Over the past several years epidemiologic studies and novel data have mandated that the primary care clinician redirect this office visit to include a broader definition of both sexual function and dysfunction: premature ejaculation, libido and hypogonadism, and the potential medical causes of each of these. Given the value of Thompson’s study, a cardiovascular assessment and an even broader cardiometabolic risk assessment should be performed in light of the data suggesting that ED may be a sentinel sign of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The next section provides the rationale for this global assessment paradigm in primary care and other men’s health topics including sexual issues, but does not include other pertinent topics of men’s health including affective and mood disorders, domestic and partner violence, and other gender-specific issues. Disparities among multicultural differences in men’s health, as it exists in a socioeconomic means and disease prevalence among various multiethnic groups, are beyond the scope of this article.

Who is the Men’s Health doctor: primary care physician versus primary care physician Men’s Health subspecialist versus urologist

While urologists are typically thought of as men’s doctors as obstetricians/gynecologists are considered women’s doctors , the issue remains as to who is to shoulder this responsibility in the decades to come, regardless of reform. Will it be a shared care approach, including clear communication between urologists and primary care clinicians, and vice versa, or do we need to enhance this relationship or specialty? Do we need to create separate “Centers of Excellence” for men’s health, as the author has strived to do at the Miriam Hospital and Warren Alpert School of Medicine of Brown University? Do we need to establish Men’s Health Fellowships for nonurologists dealing more with the issues of “medical urology?” Having practiced as a primary care clinician for over 25 years before opening this Center of Men’s Health 2 years ago (composed of urological, psychological, and comprehensive cardiometabolic medical evaluation), I (the author of this article) feel a need to reflect on past and present experience.

First, what I miss most from routine primary care is longitudinal care compressed into a series of vignettes, no greater than 10 to 15 minutes, spanning the course of decades. There is a sense of familiarity and rapport that is immediate and refreshed in each visit. The patient’s concerns are varied, often multiple and unpredictable, and require rapid thinking, concise summations, and treatment plans. I came to treasure these encounters, and felt validated and loved by my patients.

Second, I have struggled to morph myself into a subspecialist from a primary care clinician. In my former life, I dictated or charted solely for myself and my cross-covering peers, and not for review as a referring subspecialist. With this additional role, my language must be supportive, direct, and nonprovocative. I must recognize the boundaries of my work, make recommendations, but recognize that as one primary care provider/subspecialist speaking to another, the tone and content of my charting has to focus almost entirely on evidence-based medicine, noting the studies rationalizing my suggesting the use of an angiotensin receptor blocker/angiotensin-converting enzyme for this patient’s hypertension and sexual function, or the addition of bupropion to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. I must take caution to recommend a slow taper of the noncardioselective β-blocker in the post–myocardial infarction patient, now 3 years out, and replacement with perhaps a more sexually friendly and endothelial enhancing drug such as nebivolol. When I suggest a means to improve diabetic control, including focus on lifestyle and diet, or perhaps a more aggressive stance to managing dyslipidemia, I must proceed with caution. Who am I and what training do I have to make these recommendations? Most internists to whom I correspond do not know of the years spent at American Urological Association (AUA) meetings, boards, committees, and self-developed preceptorships I have encountered. Nor do they know of the tumultuous path to election to the Sexual Medicine Society of North America’s fellowship and Board of Directors, and membership to the AUA’s Committee on Men’s Health. To them, I can easily be accused of assuming primary care for the patient. And indeed, there may be some accuracy to this claim in the post–radical prostatectomy “penile-rehab” patient when I am aggressively suggesting control of cardiometabolic risk factors and neuromodulation with statins, to name examples. It is clear that without the background knowledge, the primary care clinician may misinterpret my goals and rationale.

Therefore, not to be accused of “co-opting” primary care patients from one clinician to another, I must presently recognize when it is time to step aside, relinquish my duties and contact with patients with whom I have become quite fond of over the past 2 years during their rehabilitation, and steadfastly refuse overtures to become their primary care physician. My appeal may be that I am focusing on a single, highly personal medical problem, their sexual dysfunction, and not the usual laundry-list of the standard primary care visit: type 2 diabetes; hypertension; dyslipidemia; sprinkled with a bit of generalized anxiety.

Our interactions in the Men’s Health Center are not replicated in the world of volume primary care, and I am the first to acknowledge the wondrous reality of my situation and its accompanying depth of interaction and emotional content. Indeed, my focus is often as much “lifestyle coach” as it is cardiometabolic medicine.

Which system is better? This is yet to be known. In my former life as primary care physician whereby I incorporated this interest of sexual medicine into my daily practice, I saw on average 34 to 36 patients per day, short-changing much thought and discussion to remain respectful of patients’ (and my) time, yet bringing sessions to a close with a warm touch of the arm or shoulder, and some genuine laughter. Contrast this to the Men’s Health Center, where each patient has a similar “template” and complaints are relatively a known quantity, as are patients’ stories. Though I approach the second with passion, excitement, and “reflective listening,” maintaining eye contact, we may not know the answer to this question until we have objective outcomes. However, intuitively I feel that this combination of urologist-andrologist/internal medicine-family physician/psychologist-sex therapist is most unusual and offers a unique opportunity to enhance gender-specific care. Routinely individuals see two providers at the initial visit: urologist/internist or internist/psychologist. I am kidded by the urologists; my notes still begin with a story: married, divorced, or living with wife and children; partnered or semi-partnered; open-married or close-married; job satisfaction; life stresses; and partner relationship. Again, the good in this model is my focus on the “whole” male.

Historically, the office visit for a man complaining of sexual dysfunction focused solely on ED, and this was the narrow definition of men’s health. Over the past several years epidemiologic studies and novel data have mandated that the primary care clinician redirect this office visit to include a broader definition of both sexual function and dysfunction: premature ejaculation, libido and hypogonadism, and the potential medical causes of each of these. Given the value of Thompson’s study, a cardiovascular assessment and an even broader cardiometabolic risk assessment should be performed in light of the data suggesting that ED may be a sentinel sign of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The next section provides the rationale for this global assessment paradigm in primary care and other men’s health topics including sexual issues, but does not include other pertinent topics of men’s health including affective and mood disorders, domestic and partner violence, and other gender-specific issues. Disparities among multicultural differences in men’s health, as it exists in a socioeconomic means and disease prevalence among various multiethnic groups, are beyond the scope of this article.

The primary care office visit as a portal to men’s health: male sexual evaluation

Erectile Dysfunction

Definition

For years, the terms impotence and ED had been used interchangeably to denote the inability of a man to achieve or maintain erection sufficient to permit satisfactory sexual intercourse. Social scientists objected to the impotence label, because of its pejorative implications and lack of precision. A National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Conference advocated that ED be used in place of the term impotence. ED or impotence was now defined as “the inability of the male to achieve an erect penis as part of the overall multifaceted process of male sexual function.” This definition deemphasizes intercourse as the sine qua non of sexual life, and gives equal importance to other aspects of male sexual behavior.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that at least 10 to 20 million American males suffer from ED. Laumann and colleagues have shown that the prevalence of male sexual dysfunction approaches 31% in a population survey of approximately 1400 men aged 18 to 59 years; in the National Health and Social Life Survey hypogonadism (5%), ED (5%), and premature ejaculation (21%) were the 3 most common male sexual dysfunctions noted.

The Massachusetts Male Aging Study, a large epidemiologic study, asked men between the ages of 40 and 70 years to categorize their erectile function as either completely, moderately, minimally, or not impotent. Fifty-two percent of the sample reported some degree of ED. This study demonstrated that ED is an age dependent disorder; “between the ages of 40–70 years the probability of complete impotence tripled from 5.1% to 15%, moderate impotence doubled from 17 to 34% while the probability of minimal impotence remained constant at 17%.” By age 70, only 32% portrayed themselves as free of ED. Finally, cigarette smoking increased the probability of total ED in men with treated heart disease, hypertension, or untreated arthritis. It similarly increased the probability for men on cardiac, antihypertensive, or vasodilator medications.

After the data were adjusted for age, men treated for diabetes (28%), heart disease (39%), and hypertension (15%) had significantly higher probabilities for ED than the sample as a whole (9.6%). Men with untreated ulcer (18%), arthritis (15%), and allergy (12%) were also significantly more likely to develop ED. Although ED was not associated with total serum cholesterol, the probability of dysfunction varied inversely with high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol.

Certain classes of medication were related to increased probability for total ED. The percentage of men with complete dysfunction taking hypoglycemic agents (26%), antihypertensives (14%), vasodilators (36%), and cardiac drugs (28%) was significantly higher than the sample as a whole (9.6%).

More recent data added greater depth to the United States national estimates of ED. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, collected data by household interview supplemented by medical examination. The sample size for the entire survey for the 2-year period was 11,039, with a response rate of 71.1% for men 20 years and older. Data include medical histories in which specific queries are made regarding sexual function. In men 20 years and older, ED affected almost 1 in 5 respondents. Hispanic men were more likely to report ED (odds ratio [OR], 1.89), after controlling for other factors. The prevalence of ED increased dramatically with advanced age; 77.5% of men 75 years and older were affected. In addition, there were several modifiable risk factors that were independently associated with ED, including diabetes mellitus (OR, 2.69), obesity (OR, 1.60), current smoking (OR, 1.74), and hypertension (OR, 1.56).

Relationship between ED and cardiovascular disease

Data specific to ED and related diseases has emerged, and serves to support the relationship between ED and CVD. Seftel and colleagues quantified the prevalence of diagnosed hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and depression in male health plan members (United States) with ED, using a nationally representative managed care claims database that covered 51 health plans with 28 million lives for 1995 through 2002. Crude population prevalence rates in this study population were 41.6% for hypertension, 42.4% for hyperlipidemia, 20.2% for diabetes mellitus, 11.1% for depression, 23.9% for hypertension and hyperlipidemia, 12.8% for hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and 11.5% for hyperlipidemia and depression. The crude age-specific prevalence rates varied across age groups significantly for hypertension (4.5%–68.4%), hyperlipidemia (3.9%–52.3%), and diabetes mellitus (2.8%–28.7%), and significantly less for depression (5.8%–15.0%). Region-adjusted population prevalence rates were 41.2% for hypertension, 41.8% for hyperlipidemia, 19.7% for diabetes mellitus, and 11.9% for depression. Of 87,163 patients with ED (32%) had no comorbid diagnosis of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, or depression. These data suggested and confirmed that hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and depression were prevalent in patients with ED. This evidence supported the proposition that ED shares common risk factors with these 4 concurrent conditions, supporting the view that ED could be viewed as a potential observable marker for these concurrent CVD risk conditions.

Further epidemiologic data have suggested that ED may be an early marker for actual CVD. Min and colleagues studied 221 men referred for stress myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography (MPS) commonly used to diagnose and stratify CVD. It was found that 55% of the patients had ED, and that these men exhibited more severe coronary heart disease (MPS summed stress score >8) (43% vs 17%; P <.001) and left ventricular dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction <50%) (24% vs 11%; P = .01) than those without ED. These data suggested that ED might be an independent predictor of more severe coronary artery disease and high-risk MPS findings.

Evolving data support the ED-cardiovascular paradigm. A sample of nearly 4000 Canadian men, aged 40 to 88 years, seen by primary care clinicians reported ED with the use of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF). The presence of CVD or diabetes mellitus increased the probability of ED, and among those individuals without CVD or diabetes mellitus the calculated 10-year Framingham coronary risk increase and fasting glucose level increase were independently associated with ED. ED was also independently associated with undiagnosed hyperglycemia (OR, 1.46), impaired fasting glucose (OR, 1.26) and the metabolic syndrome (OR, 1.45).

The prospective analysis discussed in the introduction by Thompson and colleagues of the nearly 9500 men randomly assigned to the placebo arm of the PCPT revealed that men with ED are at significantly greater risk ( P <.001) of having a cardiovascular event—angina, myocardial infarction, or stroke—than those without ED. Furthermore, the findings indicate that the relationship between incident ED (the first report of ED of any grade) and CVD is comparable with that associated with current smoking, family history of myocardial infarction, or hyperlipidemia. Subsequent to the Thompson analysis and lending further support to the idea of ED as a precursor of CVD, Montorsi and colleagues in the COBRA study investigated 285 patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). A key finding is that nearly all patients who developed CAD symptoms experienced ED symptoms first, on average 2 to 3 years beforehand. Finally, ED and CVD share a similar pathogenic involvement of the nitric oxide pathway, leading to impairment of endothelium-dependent vasodilatation (early phase) and structural vascular abnormalities (late phase). Thus, ED may be considered as the clinical manifestation of a vascular disease affecting the penile circulation; likewise, angina pectoris is the clinical manifestation of a vascular disorder affecting coronary circulation.

Moreover, while there is growing opinion that ED is an index of subclinical coronary disease and a precursor of cardiovascular events, a variety of mechanisms have been proposed. ED could be a predictor because it leads to depression, which leads in turn to increased cardiac risk. Or men with ED may have higher body mass index (BMI) or other comorbidities that leads to both ED and CAD.

As the Thompson study lent further support to the notion that ED is predominantly a disease of vascular origin, with endothelial cell dysfunction as the unifying link, investigations in diabetics have also supported this concept, and in fact suggest that ED is a predictor of future cardiovascular events in this group. Gazzaruso and colleagues recruited 291 type 2 diabetic men with silent CAD and found that those who developed major adverse cardiac events over the course of approximately 4 years were more likely to have ED (61.2%) than those who did not (36.4%). Through further multivariate analysis, ED remained an important predictor of adverse cardiac events, and although diabetics have ahigh risk of CVD, the risk is even higher in those who develop ED.

Ma and colleagues studied 2306 diabetic men with no clinical evidence of CAD, of whom 27% had ED. Over the course of approximately 4 years, the incidence of coronary heart disease was greater in men with ED (19.7/1000 person-years) than in men without ED (9.5/1000 person-years). After adjustments for other covariates, including age, duration of disease, antihypertensive agents, and albuminuria, ED remained an independent predictor of coronary heart disease (hazard ratio [HR] 1.58, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.08–2.30, P = .018).

Therefore, because ED and silent CAD are prevalent in the diabetic population, this should move all health care providers in primary care to inquire about sexual function in the diabetic patient, and aggressively treat cardiovascular risk factors including dyslipidemia and hypertension. Indeed, the Second Princeton Consensus Panel on sexual activity and cardiac risk published recommendations for the individual with established CAD or suspected CAD related to estimated risk for cardiovascular events, and in those individuals of intermediate or indeterminate risk (no overt cardiac symptoms and 3 or more cardiovascular risk factors including sedentary lifestyle; moderate stable angina; recent myocardial infarction <6 weeks; New York Heart Association Class II heart failure; prior stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA) or history of peripheral vascular disease) should receive further cardiac evaluation to delineate the presence and severity of coronary disease.

It is therefore recommended that physicians screen the ED patient for vascular disease, and because ED often coexists with the comorbidities of diabetes (3–4-fold incidence), hypertension, or dyslipidemia, screening in the primary care clinician’s office for ED should occur with the management of each of these comorbiities.

What does ED tell us in the nondiabetic population?

What about the nondiabetic, noncomorbid population? What does the presence of ED suggest in the lower-risk male population not yet studied to date? To this point, Inman and colleagues biennially screened a random sample of more than 1400 community-dwelling men who had regular sexual partners and no known CAD for the presence of ED over a 10-year period. Men were followed from the fourth screening round (1996) of the Olmsted County Urinary Symptoms and Health Status among Men Study until the first occurrence of an incident cardiac event or the last study visit (December 31, 2005). Men with prevalent ED at study onset were excluded from the analyses. Multivariate proportional hazard regression models were used to assess the association of the covariates of age, diabetes, hypertension, smoking status, and BMI with ED. Unlike the Thompson study or others already noted, the participants of this study were not a highly selected subset of the general male population and older than 55 years, but more representative of a normal (albeit predominantly Caucasian) group of men. In addition, erectile function of the study participants was assessed by an externally validated questionnaire, the Brief Male Sexual Function Inventory (BMSFI), a self-reported questionnaire comprising 11 items rated on a scale of 0 to 4, with higher scores representing better sexual function.

During the 10-year follow-up period, ED was modeled as a time-dependent covariate that allowed each patient’s ED status to change over time, with results stratified by 10-year age periods and adjusted for diabetes, hypertension, smoking status, and BMI.

Baseline prevalence of ED was 2% for 40-year-olds, 6% for 50-year-olds, 17% for 60-year-olds, and 39% for men older than 70. New ED developed in 6.4% at 2 years with increases of approximately 5% in each subsequent 2-year interval over the 10-year period of follow-up. Incident ED was more common in patients with higher cardiovascular risk and older age.

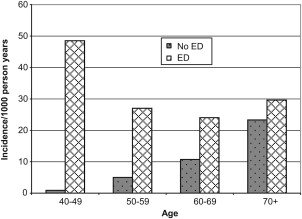

Overall, new incident CAD developed in 11% of men over the 10-year follow-up period, with approximately 15% due to myocardial infarction, 79% to angiographic anomalies, and 6% to sudden death. The cumulative incidence of CAD was strongly influenced by patient age. CAD incidence densities per 1000 person-years for men without ED were 0.94 (age 40–49), 5.09 (age 50–59), 10.72 (age 60–69), and 23.30 (age 70+). For men with ED, the incidence densities for CAD were 48.52 (age 40–49), 27.15 (age 50–59), 23.97 (age 60–69), and 29.63 (age 70+) ( Fig. 1 ).

Is ED a greater predictor of cardiovascular disease in the younger (age <60 years) male?

The meaning of these findings is most significant. While ED and CAD may be different manifestations of an underlying vascular pathology, when ED occurs in a younger man (age <60) it is associated with a marked increase in the risk of future cardiac events whereas in older men it appears to have less prognostic value. The importance of this study cannot be understated. Whereas ED had little relationship with the development of incident cardiac events in men aged 70 years and older, it was associated with a nearly 50-fold increase in the 10-year incidence in men 49 years and younger. This finding raises the possibility of a “window of curability” whereby progression of cardiac disease might be slowed or halted by medical intervention. Younger men with ED could provide the ideal populations for future studies of primary cardiovascular risk prevention.

Why younger than older men? Clearly there is a higher incidence of psychogenic ED in younger men, and the argument can be made that all ED has a psychological component. However, in the younger male with more than one cardiovascular risk factor, his ED and CAD may be different manifestations of an underlying vascular pathology. ED appears to precede symptoms of CAD in patients with a vascular etiology. Montorsi and colleagues suggest that this phenomenon relates to the caliber of the blood vessels. For example, the penile artery has a diameter of 1 to 2 mm, whereas the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery is 3 to 4 mm in diameter. An equally sized atherosclerotic plaque burden in the smaller penile arteries would more likely compromise flow earlier and cause ED compared with the same amount of plaque in the larger coronary artery causing angina. In another plausible explanation, Inman and colleagues suggest greater impairment in arterial endothelial cell function with age. The repetitive pulsations to which the large central arteries are subjected over their lifespan lead to fatigue and fracture of the elastic lamellae, resulting in increased stiffness. Ultimately small arteries such as the pudendal and penile arteries begin to degenerate and end-organ ischemia results. In the younger male with ED, impaired vasodilation of a penile artery is more likely to lead to ED, even in the absence of atherosclerotic plaque narrowing the lumen, than in the same scenario in the coronary arteries leading to symptoms of angina.

Hacket goes further to elaborate that the treatment of ED with phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors as a class, and particularly in studies demonstrated with sildenafil and tadalafil, has been shown to dilate epicardial coronary arteries, improve endothelial dysfunction, and inhibit platelet activation in patients with CAD. The availability of effective, noninvasive treatment methods, which have a significant impact on the quality of life of men with ED, means that an increase in the diagnosis of ED could benefit a large number of men and their partners, and potentially improve the pathology leading to the condition itself.

Although ED is associated with cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis, it is not known whether the presence of ED is predictive of future events in individuals with known CVD. Bohm and colleagues evaluated whether ED is predictive of mortality and cardiovascular outcomes, and because inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system in high-risk patients reduces cardiovascular events, wished to establish whether there are protective effects of the pharmacologic inhibition of this system. Therefore, the investigators additionally tested the effects on ED of randomized treatments with telmisartan, ramipril, and the combination of the two drugs (ONTARGET), as well as with telmisartan or placebo in patients who were intolerant of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (TRANSCEND).

In a prespecified substudy, 1549 patients, of whom 842 had a history of ED at baseline and were slightly older (65.8 years vs 63.6 years, P <.0001) with a higher prevalence of hypertension, stroke/TIA, diabetes mellitus, and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), underwent double-blind randomization, with 400 participants assigned to receive ramipril, 395 telmisartan, and 381 the combination thereof (ONTARGET), as well as 171 participants assigned to receive telmisartan and 202 placebo (TRANSCEND). ED was evaluated at baseline, at 2-year follow-up, and at the penultimate visit before closeout. Because of the nature of the study population, incident ED or new-onset ED clearly was small. However, either baseline or incident ED was predictive of all-cause death (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.21–2.81, P = .005) and the composite primary outcome (HR 1.42, 95% CI 1.04–1.94, P = .029), which consisted of cardiovascular death (HR 1.93, 95% CI 1.13–3.29, P = .016), myocardial infarction (HR 2.02, 95% CI 1.13–3.58, P = .017), hospitalization for heart failure (HR 1.2, 95% CI 0.64–2.26, P = .563), and stroke (HR 1.1, 95% CI 0.64–1.9, P = .742). The study medications did not influence the course or development of ED.

ED is a potent predictor of all-cause death and the composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure in men with CVD. Trial treatment with either telmisartan or ramipril did not significantly improve or worsen ED. This finding is somewhat surprising given these agents’ beneficial effects on endothelial cell function.

Whether ED is only a risk marker or may even be considered a “CAD risk equivalent” (an independent risk factor) is not yet fully clarified; yet there is evidence to consider all men with ED younger than 60 years to be at risk of CVD until proved otherwise. However, given the high prevalence of ED in the middle-aged population, a systematic cardiologic screening would not be cost effective. Therefore, it is crucial to identify ED patients at high risk for occult CAD or acute coronary events, or both. The task for the clinician is to identify those patients with ED who may be at intermediate or high risk for subsequent CVD. A reasonable first step is to estimate, through one of several risk assessment office-based approaches, the subject’s own relative and absolute risk of a cardiovascular event (usually in the following 10 years). Lloyd-Jones and colleagues recommend incorporating a stepwise approach to cardiovascular risk stratification, with the Framingham criteria used for all patients and the lifetime analysis added for those predicted to be at low 10-year risk. This type of systematic analysis and use of the Princeton II guidelines can help the practitioner distinguish between the presence of organic and cardiovascular risk versus largely psychological etiology in this middle-aged ED patient.

The aforementioned studies suggest that a presentation of ED should trigger an assessment of cardiovascular risk factors and, if appropriate, vigorous intervention.

Psychosocial morbidity of ED

The impact of ED frequently extends beyond a man’s physical function; it can have a psychological effect on a man and his partner, producing disquiet. Consequently, the emotional toll that ED can have on men and their partners should be considered in the diagnosis and management of ED. A global survey of 13,618 men from 29 countries found that 13% to 28% have ED, and a survey of 1481 men in the Netherlands found that, of those with ED, 67% were bothered by it and 85% wanted help for their condition. Left untreated, the emotional distress associated with ED can significantly affect important psychosocial factors, including self-esteem and confidence, and damage personal relationships. In their Consensus Development Panel on Impotence, the NIH recommended that studies continue to investigate the social and the psychological effects of ED in patients and their partners. However, there are few data on the effect of ED and its treatment on trouble associated with ED, which may be due in part to the absence of data from an instrument designed to assess the bother or distress that is specific to ED.

Summary and recommendations

ED is a common men’s sexual health complaint, increases in prevalence with aging, is bothersome, and is a future marker for CVD. A verbal inquiry or a brief written 5-item survey (SHIM) can be used to quantify the degree of ED, and thereby the concomitant risk of CVD. ED is associated with hypertension, diabetes, depression, hyperlipidemia, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity. Thus, the man presenting to the clinician complaining of ED should have these areas explored. In addition to defining and characterizing the specific sexual complaint (discussed later), a brief cardiovascular assessment of risk factors, including smoking, lifestyle and exercise, diet, blood pressure, lipids, weight, and distress, should all be part of the initial evaluation. A World Health Organization consensus panel has deliberated and agreed that these recommendations about associating ED with the need for a CVD evaluation are reasonable.

Hypogonadism (Testosterone Deficiency)

Definition

The US FDA has accepted a total testosterone (TT) level of 300 ng/dL as the lower limit of normal for serum testosterone levels. Others have challenged this level, citing a variety of reasons as to why a level of 300 ng/dL is not a true reflection of hypogonadism. Reasons include a lack of age-specific norms, a lack of evidence that 300 ng/dL is aproper number, and a lack of symptoms reflecting what the testosterone level represents. Clinicians have gravitated to the term “late-onset hypogonadism” to suggest that an older group of men might be a more appropriate group of individuals on whom we should focus with respect to testosterone deficiency. An international consensus statement (published in 3 to 4 journals simultaneously) has offered the following guidance.

- 1.

Definition of late-onset hypogonadism (LOH): A clinical and biochemical syndrome associated with advancing age and characterized by typical symptoms and a deficiency in serum testosterone levels. It may result in significant detriment in the quality of life and adversely affect the function of multiple organ systems.

- 2.

LOH is a syndrome characterized primarily by:

- a.

The easily recognized features of diminished sexual desire (libido) and erectile quality and frequency, particularly nocturnal erections

- b.

Changes in mood with concomitant decreases in intellectual activity, cognitive functions, spatial orientation ability, fatigue, depressed mood, and irritability

- c.

Sleep disturbances

- d.

Decrease in lean body mass with associated diminution in muscle volume and strength

- e.

Increase in visceral fat

- f.

Decrease in body hair and skin alterations

- g.

Decreased bone mineral density resulting in osteopenia, osteoporosis, and increased risk of bone fractures.

- a.

Epidemiology

A recent review of this topic sheds light on the epidemiology of hypogonadism. In healthy, young eugonadal men, serum testosterone levels range from 300 to 1050 ng/dL, but decline with advancing age, particularly after 50 years. Using a serum testosterone level of 325 ng/dL, the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) reported that approximately 12%, 20%, 30%, and 50% of men in their 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s, respectively, are hypogonadal.

The Hypogonadism in Males (HIM) study estimated the prevalence of hypogonadism (TT <300 ng/dL) in men aged 45 years or older visiting primary care practices in the United States. A blood sample was obtained between 8 am and noon and was assayed for TT, free testosterone (FT), and bioavailable testosterone (BAT). Common symptoms of hypogonadism, comorbid conditions, demographics, and reason for visit were recorded. Of 2162 patients, 836 were hypogonadal, with 80 receiving testosterone. The crude prevalence rate of hypogonadism was 38.7%. Similar trends were observed for FT and BAT.

Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have demonstrated annual testosterone decrements of 0.5% to 2% with advancing age. The rate of decline in serum testosterone in men appears to be largely dependent on their age at study entry. In the BLSA, the average decline was 3.2 ng/dL per year among men aged 53 years at entry. On the other hand, the New Mexico Aging Process Study of men 66 to 80 years old at entry showed a decrease in serum testosterone of 110 ng/dL every 10 years. Although serum testosterone levels are generally measured in the morning when at peak, this circadian rhythm is often abolished in elderly men.

Testing for hypogonadism and determining who requires testosterone replacement

The recommendations of the International Society of Andrology, International Society for the Study of the Aging Male, and European Association of Urology note that in patients at risk for or suspected of hypogonadism in general and LOH in particular, a thorough physical and biochemical workup is mandatory and in particular, the following biochemical investigations should be done:

- 1.

A serum sample for total T determination and sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) should be obtained between 07.00 and 11.00 hours. The most widely accepted parameters to establish the presence of hypogonadism are the measurement of TT and FT calculated from measured TT and SHBG or measured by a reliable FT dialysis method.

- 2.

There are no generally accepted lower limits of normal, and it is unclear whether geographically different thresholds depend on ethnic differences or on the physician’s perception. There is, however, general agreement that TT levels above 12 nmol/L (346 ng/dL) or FT levels above 250 pmol/L (72 pg/mL) do not require substitution. Similarly, based on the data from younger men, there is consensus that serum TT levels below 8 nmol/L (231 ng/dL) or FT below 180 pmol/L (52 pg/mL) require substitution. Since symptoms of testosterone deficiency become manifest between 12 and 8 nmol/L, trials of treatment can be considered in those in whom alternative causes of these symptoms have been excluded. (Since there are variations in the reagents and normal ranges among laboratories, the cutoff values given for serum T and FT may have to be adjusted depending on the reference values given by each laboratory.)

- 3.

If testosterone levels are below or at the lower limit of the accepted normal adult male values, it is recommended to perform a second determination together with assessment of serum luteinizing hormone and prolactin.

- 4.

A clear indication, based on a clinical picture together with biochemical evidence of low serum testosterone, should exist prior to the initiation of testosterone substitution.

The Endocrine Society has recently published its set of guidelines, entitled “Testosterone Therapy in Adult Men with Androgen Deficiency Syndromes: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline,” which has been updated this year.

The Endocrine Society recommends making a diagnosis of androgen deficiency only in men with consistent symptoms and signs and unequivocally low serum testosterone levels. These recommendations include the measurement of morning TT level by a reliable assay as the initial diagnostic test. Confirmation of the diagnosis is suggested, by repeating the measurement of morning TT and in some patients by measurement of FT or BAT level, using accurate assays. Overall the Society recommends testosterone therapy for symptomatic men with androgen deficiency, who have low testosterone levels, to induce and maintain secondary sex characteristics and to improve their sexual function, sense of well-being, muscle mass and strength, and bone mineral density.

These recommendations prohibit starting testosterone therapy in patients with breast or prostate cancer, a palpable prostate nodule, or induration or prostate-specific antigen (PSA) greater than 3 ng/mL without further urological evaluation, erythrocytosis (hematocrit >50%), hyperviscosity, untreated obstructive sleep apnea, severe LUTS with International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) greater than 19, or class III or IV heart failure. When testosterone therapy is instituted, they suggest aiming at achieving testosterone levels during treatment in the mid-normal range with any of the approved formulations, chosen on the basis of the patient’s preference, consideration of pharmacokinetics, treatment burden, and cost. Men receiving testosterone therapy should be monitored using a standardized plan.

In 2004, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) reviewed the current state of knowledge about testosterone therapy in older men, concluding:

As the FDA-approved treatment for male hypogonadism, testosterone therapy has been found to be effective in ameliorating several symptoms in markedly hypogonadal males. Researchers have carefully explored the benefits of testosterone therapy particularly placebo-controlled randomized trials, in the population of middle aged or older men who do not meet all the clinical diagnostic criteria for hypogonadism but who may have testosterone levels in the low range for young adult males and show one or more symptoms that are common to both aging and hypogonadism.

The IOM further concluded that “assessments of risks and benefits have been limited and uncertainties remain about the value of this therapy in older men.”

Shames and colleagues of the US FDA conclude that:

We support the right of individual physicians to treat patients based on their own knowledge or advice from known experts in the field. However, patients should be able to choose therapies based on accurate and evidence-based medical information and consultation with well-informed health care providers. Clinical guidelines and patient guides should be based on solid clinical evidence and must convey this information clearly and accurately to physicians and patients.

The IOM report also cited evidence for a possible association of low endogenous testosterone with components of the metabolic syndrome, which has been defined in various ways but generally includes insulin resistance, obesity, abnormal lipid profiles, and borderline or overt hypertension. Recent studies have confirmed that hypogonadism predisposes men to insulin resistance, obesity, abnormal lipid profiles, and borderline or overt hypertension. In 2005, a systematic review concluded that evidence linking hypogonadism and metabolic syndrome is of sufficient strength that the definition of the metabolic syndrome in men may be expanded in the future to include hypogonadism as a diagnostic parameter.

Among men with diabetes, the prevalence of hypogonadism has been reported to range from 20% to 64%. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 prospective and cross-sectional studies concluded that men with type 2 diabetes had significantly lower concentrations of testosterone than did men with normal fasting glucose.

Recent clinical studies have confirmed that TT is inversely associated with BMI, waist-hip ratio, and percentage body fat and insulin resistance. Insulin resistance among hypogonadal men may be an indirect effect of changes in body composition, inhibition of lipoprotein lipase, or decreased circulating free fatty acids. A series of data analyses from the Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study, conducted in Finland, reported that nondiabetic men were nearly fourfold more likely to develop metabolic syndrome if they were hypogonadal, twice as likely to develop diabetes or metabolic syndrome within an 11-year period if they were in the lowest quartile for testosterone levels, and up to 2.9 times as likely to develop hypogonadism during the 11-year follow-up period if they had metabolic syndrome at baseline. Therefore, it is highly evident that low testosterone is positively correlated with the onset of metabolic syndrome, and perhaps of type 2 diabetes. This correlation may have clinical and economic significance because of the high prevalence and substantial costs of diabetes and metabolic syndrome in the United States.

Potential reversibility of the link between metabolic syndrome and hypogonadism was suggested by an observational study and arecent interventional study. In the observational study, new-onset hypogonadism was 5.7 to 7.4 times more common among men with metabolic syndrome at baseline and at final visit, and approximately 3 times more common among men who also had new-onset metabolic syndrome; however, no increased risk of hypogonadism was observed among men who had metabolic syndrome at baseline that had resolved by the final visit. In the interventional study of 58 obese men with metabolic syndrome, the prevalence of hypogonadism (TT <317 ng/dL) was 48% at baseline, 9% after the men lost an average of 16.3 kg on a very low-calorie diet, and 21% when men regained approximately 2 kg on average during a 12-month weight maintenance program. Significant improvements in insulin sensitivity, fasting glucose, HDL levels, and triglycerides were observed at the end of each treatment phase.

Emerging evidence suggests that the opposite is true as well—namely, that testosterone replacement therapy may ameliorate some of the elements of metabolic syndrome—but results of these studies have been mixed ( Table 1 ). Several studies have reported that testosterone replacement therapy in hypogonadal men decreased body weight, waist-hip ratio, and body fat, and improved glycemic control, insulin resistance, and/or the lipid profile. However, some of these studies reported that one or more of the parameters of metabolic syndrome were not significantly improved by testosterone replacement therapy. Additional long-term studies are needed to elucidate the role of testosterone replacement therapy in improving body composition and clinical outcomes associated with the metabolic syndrome.