Background

The management of renal and ureteral calculi has most often been thought to be limited to surgical removal techniques. While there have been significant advances in the minimally invasive management of symptomatic calculi, equally impressive progress has been made in medical management of stone disease. The following chapter will highlight the medical management of ureteral calculi in the acute setting and the prevention of stone recurrences with medical management strategies in the long term.

Ureteral muscle spasm is thought to be one factor contributing to the impaction of ureteral stones. The physiology of ureteral smooth muscle is well studied. Numerous investigations have demonstrated that both alpha-adrenergic receptors and calcium channel antagonist binding sites exist in ureteral smooth muscle [1]. Inhibition of alpha-adrenergic receptors results in a decrease in basal tone, ureteral contractions, and ureteral peristalsis [2]. Inhibition of the voltage-dependent smooth muscle calcium channel results in a blunted rise in intracellular calcium ion concentrations during activation, leading to decreased electrical and contractile activity [3]. Because of their relatively low side effect profile, these drugs have been explored as a means to treat the ureteral spasm component of stone impaction.

Two recent meta-analyses have demonstrated statistically significant increases in spontaneous ureteral stone passage with the use of alpha-blockers and calcium channel blockers [4,5]. Many of the primary studies have also utilized corticosteroids concurrently in an effort to decrease ureteral edema and to enhance ureteral stone expulsion. In the first half of this chapter, the recent evidence supporting such medical expulsive therapy (MET) is reviewed.

Medical management strategies for the prevention of recurrent stone disease have been investigated for several decades. Several medications including thiazide diuretics, allopurinol, potassium citrate, acetohydroxamic acid, phosphate, and magnesium have been evaluated in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Thiazide diuretics stimulate resorption of calcium with concomitant excretion of sodium in the distal nephron, thereby reducing urinary calcium concentration. As an inhibitor of xanthine oxidase, allopurinol decreases the conversion of xanthine and hypoxanthine to uric acid, which results in a decrease in urinary uric acid concentration. Alkali therapy with potassium citrate increases urinary pH which improves urinary saturation of calcium oxalate and uric acid. Additionally, alkali therapy results in an increase in urinary citrate, which is a known inhibitor of calcium stone formation. Acetohydroxamic acid is an urease inhibitor and is thought to inhibit stone formation due to chronic urea-splitting organisms [6]. A lack of proven efficacy of phosphate and magnesium treatments has led to a lack of use of these two medications in the current era and they are not reviewed [7]. The current evidence supporting preventive medical therapy for recurrent stone disease is reviewed in the second half of the chapter.

Clinical question 22.1

What is the effect of alpha-adrenergic antagonist therapy on expulsion of ureteral stones?

Literature search

A search of the PubMed electronic database using the terms “drug therapy” and “nephrolithiasis or urinary calculi” limited to the “clinical trial, randomized controlled trial, or comparative study” publication types found 13 unique randomized trials dealing with the use of an alpha-blocker for MET of ureteral stones. Similar searches of CINAHL and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials did not identify any additional published randomized studies. A search of the American Urological Association (AUA) online meeting abstracts from 2002 to 2008 and the European Association of Urology (EAU) online meeting abstracts from 2004 to 2008 identified an additional three unique unpublished RCTs. One additional unpublished RCT was identified from a meta-analysis by Hollingsworth et al. [4,8].

The evidence

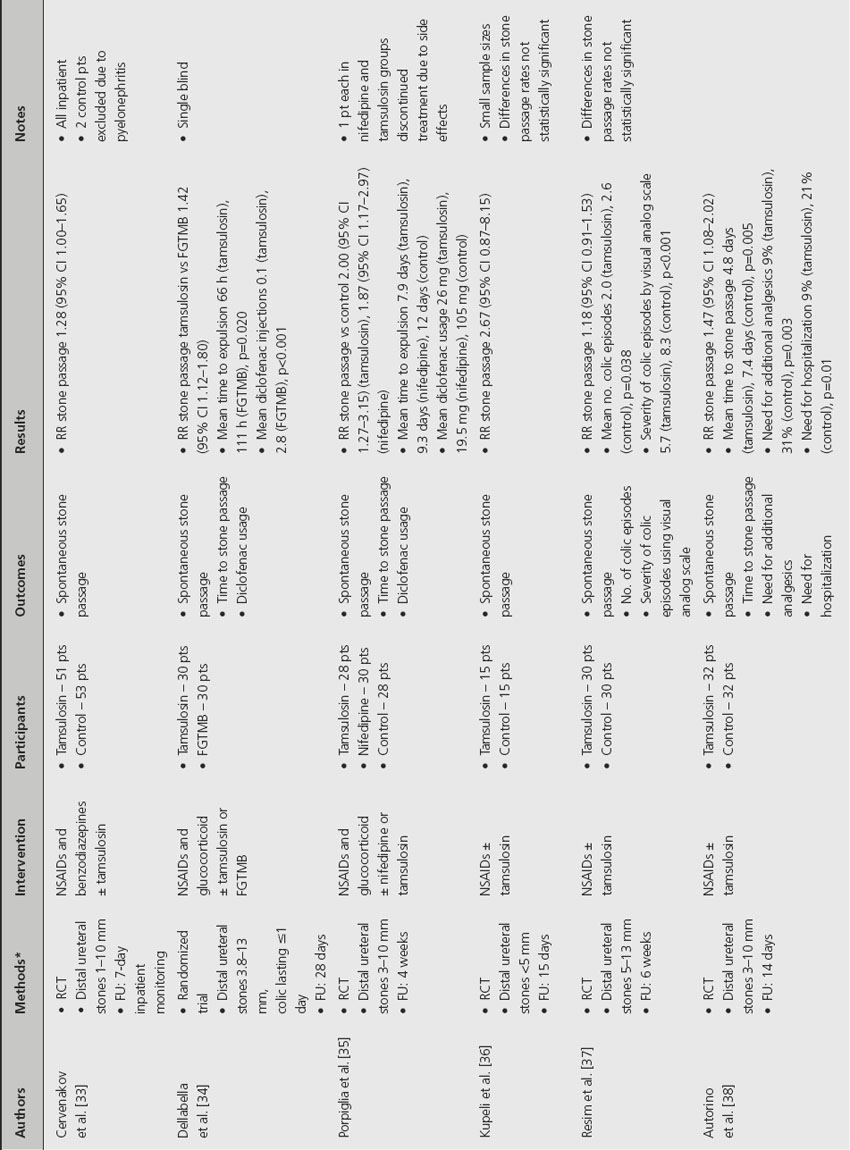

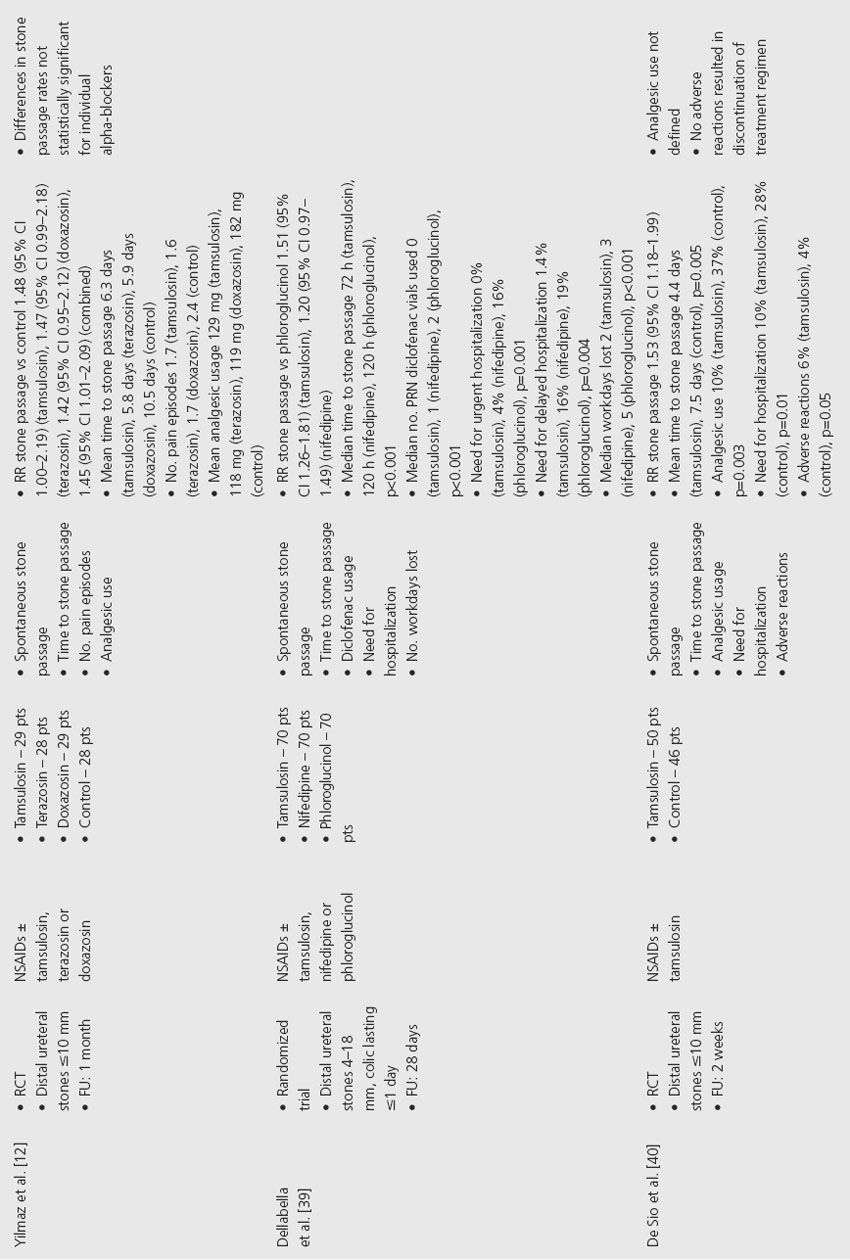

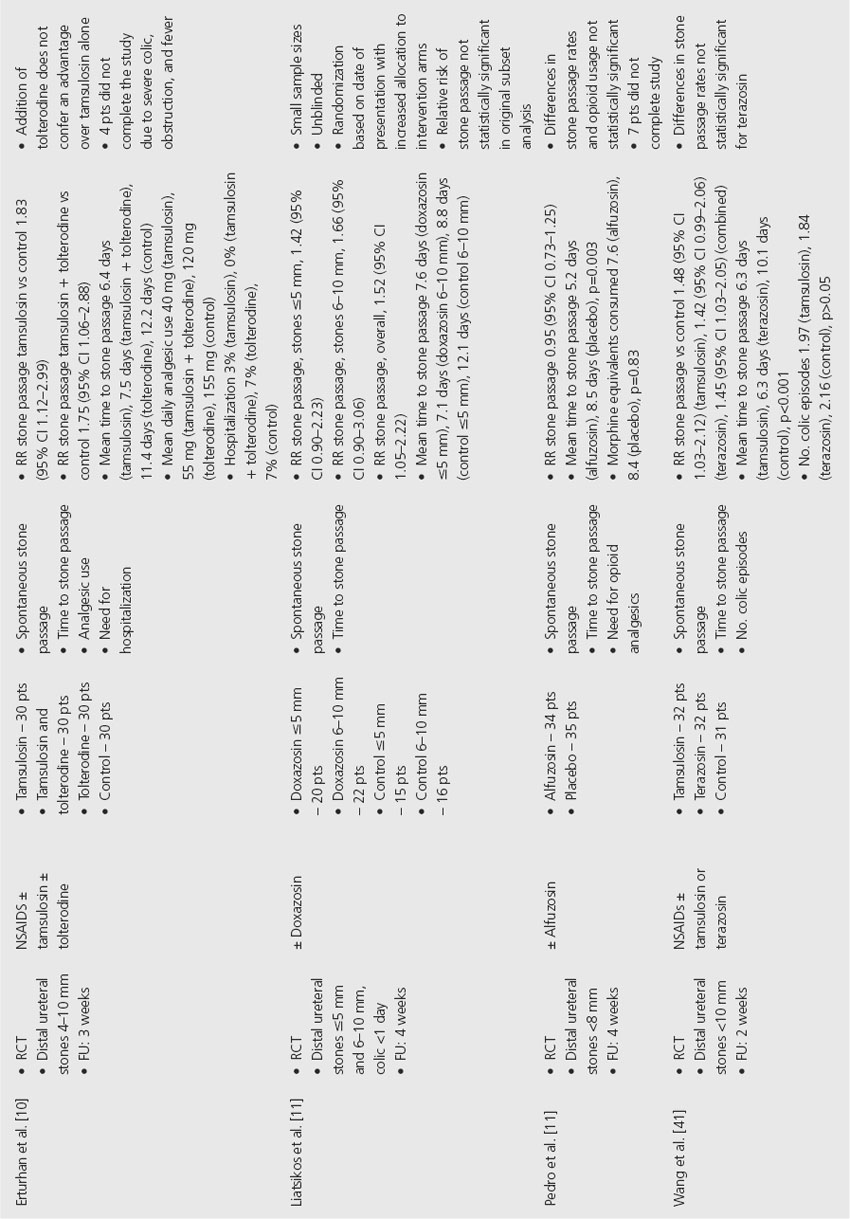

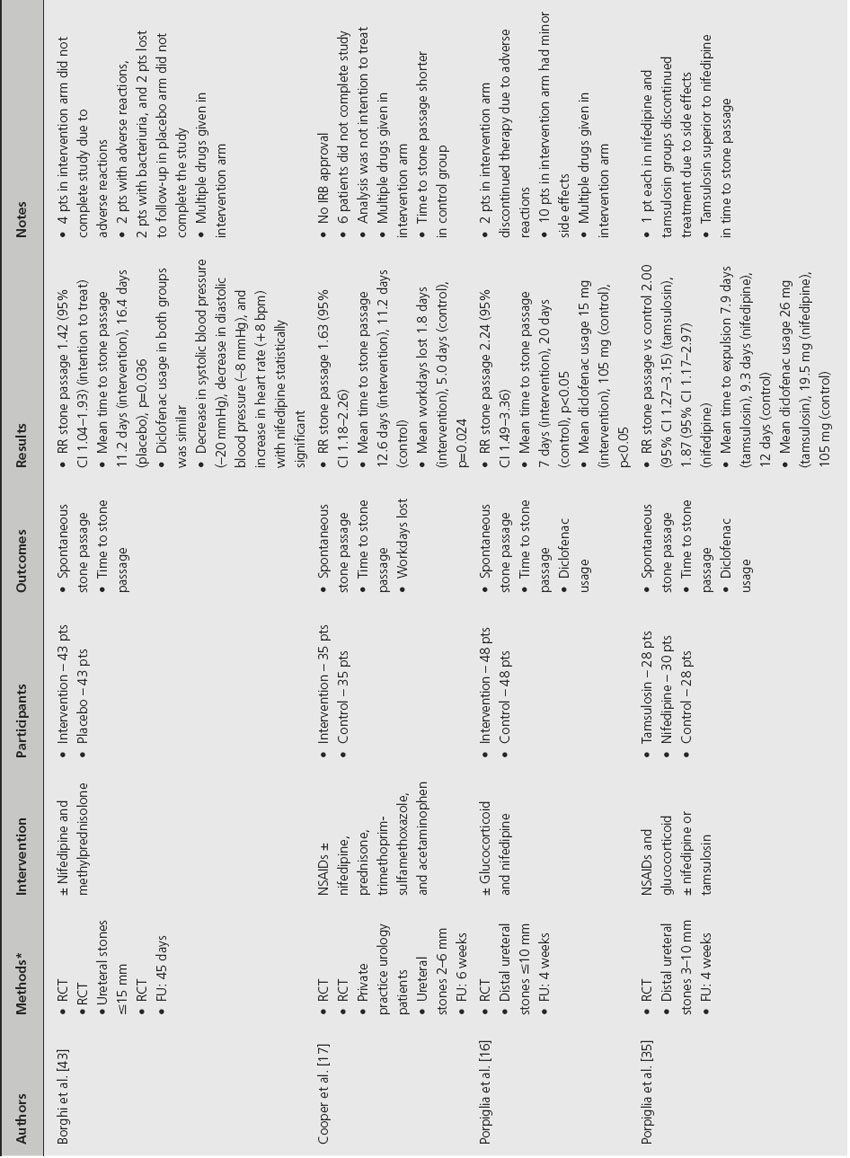

Of the 17 randomized trials that used an alpha-adrenergic antagonist for MET of stones, 13 studies utilized tamsulosin, three studies used terazosin and doxazosin, and one study used alfuzosin (Table 22.1). All trials examined patients with distal ureteral stones that ranged in size up to 18 mm who had not been previously treated with shock-wave lithotripsy. Follow-up was performed between 7 days and 6 weeks. In all but one trial, the alpha-blocker was used as the initial treatment. The exception was one trial that studied the use of the alpha-blocker after previously failed MET.

There were 10 RCTs that compared the use of tamsulosin to no additional treatment for initial MET for distal ureteral stones. An additional two randomized trials compared the use of tamsulosin to historical antispasmodics. Spontaneous stone passage rates for tamsulosin as initial therapy in individual trials ranged from a low of 53% to a high of 100%, with the overall stone passage rate being 85%. Spontaneous stone passage rates for controls in these studies ranged from a low of 20% to a high of 73%, with the overall stone passage rate being 54%. The relative risk (RR) of stone passage for initial treatment with tamsulosin ranged from 1.18 to 2.67 with an overall relative risk of 1.51 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.38–1.65) (all relative risk calculations were performed using RevMan 5.0 available at www.cc-ims.net/RevMan/). All but two trials demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in stone expulsion rates with tamsulosin. Mean/median time to stone passage ranged from 2.7 to 8.2 days versus 4.6 to 14.2 days for controls. Among those trials that examined analgesic usage, the majority demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in analgesic consumption with tamsulosin. Among the three trials that examined the number of pain/colic episodes, each showed a trend toward a decreased number of pain episodes with tamsulosin, but in only one trial was this difference statistically significant.

Porpiglia et al. studied the use of tamsulosin for 10 days after one previous failed 10-day cycle of tamsulosin as MET [9]. This trial demonstrated a RR of stone passage of 1.65 (95% CI 1.18–2.29), suggesting a statistically significant benefit to a secondary cycle of tamsulosin. There was, however, no statistical benefit in terms of the number of colic episodes and diclofenac usage with a second cycle of tamsulosin. Furthermore, the first failed cycle of tamsulosin was generally shorter than the follow-up in most studies, suggesting that a longer initial cycle of tamsulosin would have been beneficial. Erturhan et al. further studied the addition of tolterodine to tamsulosin for MET and found no statistical benefit over tamsulosin alone with regard to stone passage rate, time to stone passage, analgesic usage, and hospitalization rate, suggesting that anticholinergic usage is not beneficial [10].

Three RCTs studied the use of doxazosin as initial MET for distal ureteral stones. Spontaneous stone passage rates with doxazosin ranged from 76% to 93%, with the overall stone passage rate being 82%. Spontaneous stone passage rates for controls in these studies ranged from 52% to 61%, with an overall stone passage rate of 56%. The RR for stone passage with doxazosin ranged from 1.42 to 1.52, with an overall RR of 1.49 (95% CI 1.21–1.83). Liatsikos et al. distinguished the use of doxazosin with stones ≤ 5 mm and those 6–10 mm in size [11]. There was no statistical difference in either group when compared to controls. However, a combined analysis did demonstrate a statistically significant benefit with doxazosin. Time to stone passage was decreased with the use of doxazosin in all three studies. Yilmaz et al. also demonstrated a decreased number of pain episodes and diminished analgesic usage with doxazosin [12].

Three RCTs studied the use of terazosin as initial MET. Spontaneous stone passage rates were 78–79% with terazosin and 44–54% for controls. The RR for stone passage with terazosin ranged from 1.42 to 1.78, with only the unpublished trial by Tekin et al. demonstrating a statistically significant benefit [13]. When combined, the RR for stone passage across all three trials was 1.56 (95% CI 1.25–1.95). Mean time to stone passage ranged from 5.8 to 6.3 days for terazosin compared to 10.1 to 10.5 days for controls. The number of pain episodes also appeared to be improved with terazosin.

The RCT by Pedro et al. examined the use of alfuzosin as initial MET and found no statistical benefit in terms of spontaneous stone passage or opioid usage [14]. However, there was a statistically significant decrease in time to stone passage with alfuzosin.

Comment

The quality of the evidence for initial MET for distal ureteral stones using alpha-adrenergic antagonists is relatively high. The evidence strongly suggests that such agents are well tolerated and can significantly improve spontaneous stone passage rates, time to stone passage, and analgesic usage. The evidence is less compelling regarding decreasing the number of pain/colic episodes. The majority of studies utilized tamsulosin. The evidence for the use of other alpha-blockers in this setting is of moderate quality and will require further study.

Table 22.1 Effect of alpha-adrenergic antagonists on ureteral stone passage

In summary, a strong recommendation can be made for the use of tamsulosin as MET for distal ureteral stones based upon high-quality evidence (Grade 1A). A strong recommendation can be made for the use of other alpha-adrenergic antagonists as MET based upon moderate-quality evidence (Grade 1B).

Clinical question 22.2

What is the effect of calcium channel antagonist therapy on expulsion of ureteral stones?

Literature search

The same PubMed search used above found five unique RCTs dealing with the use of a calcium channel antagonist for MET of ureteral stones. Searches of CINAHL and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials did not identify any additional published randomized studies. A search of AUA and EAU online meeting abstracts identified an additional two unique unpublished RCTs. One additional unpublished RCT was identified from a meta-analysis by Hollingsworth et al. [4,15].

The evidence

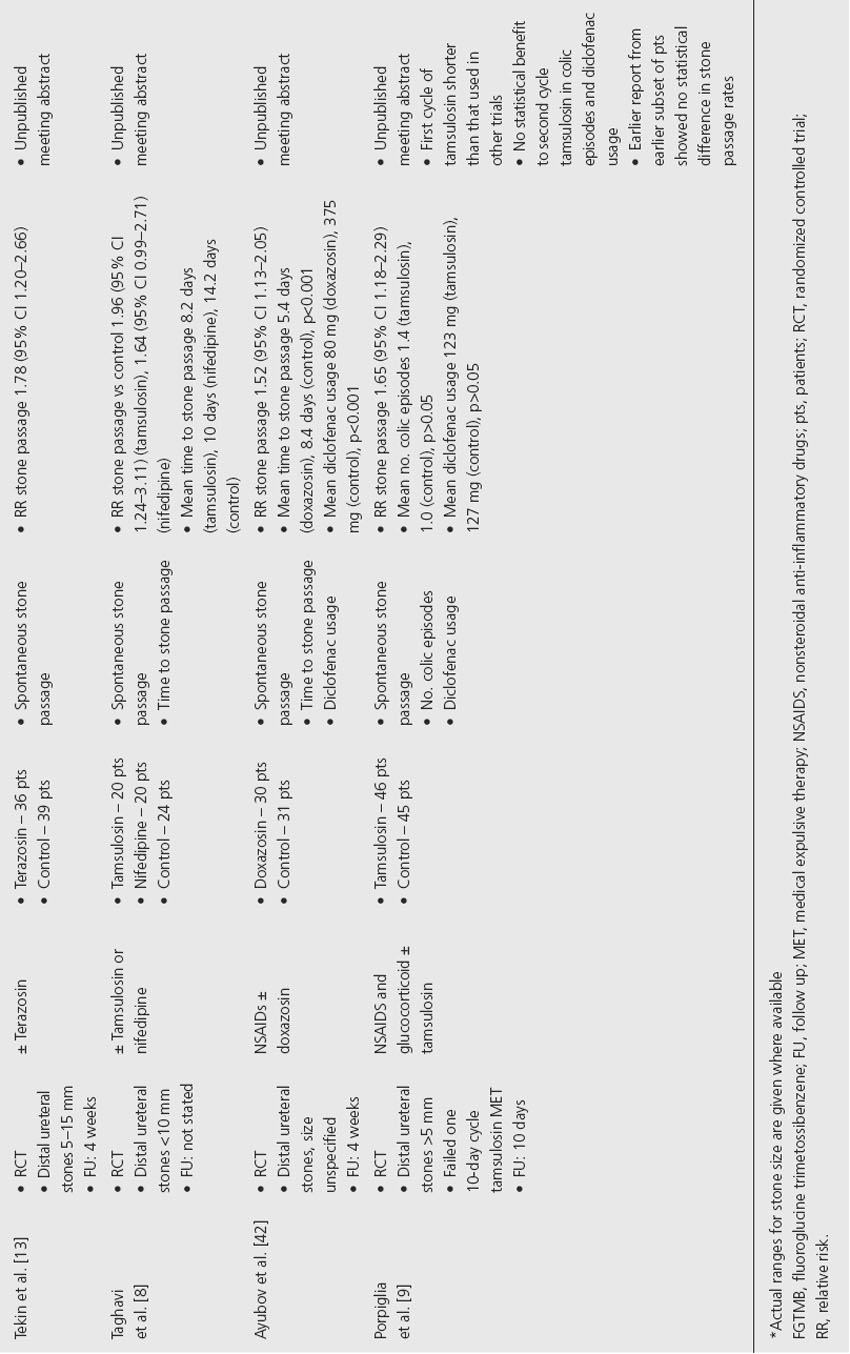

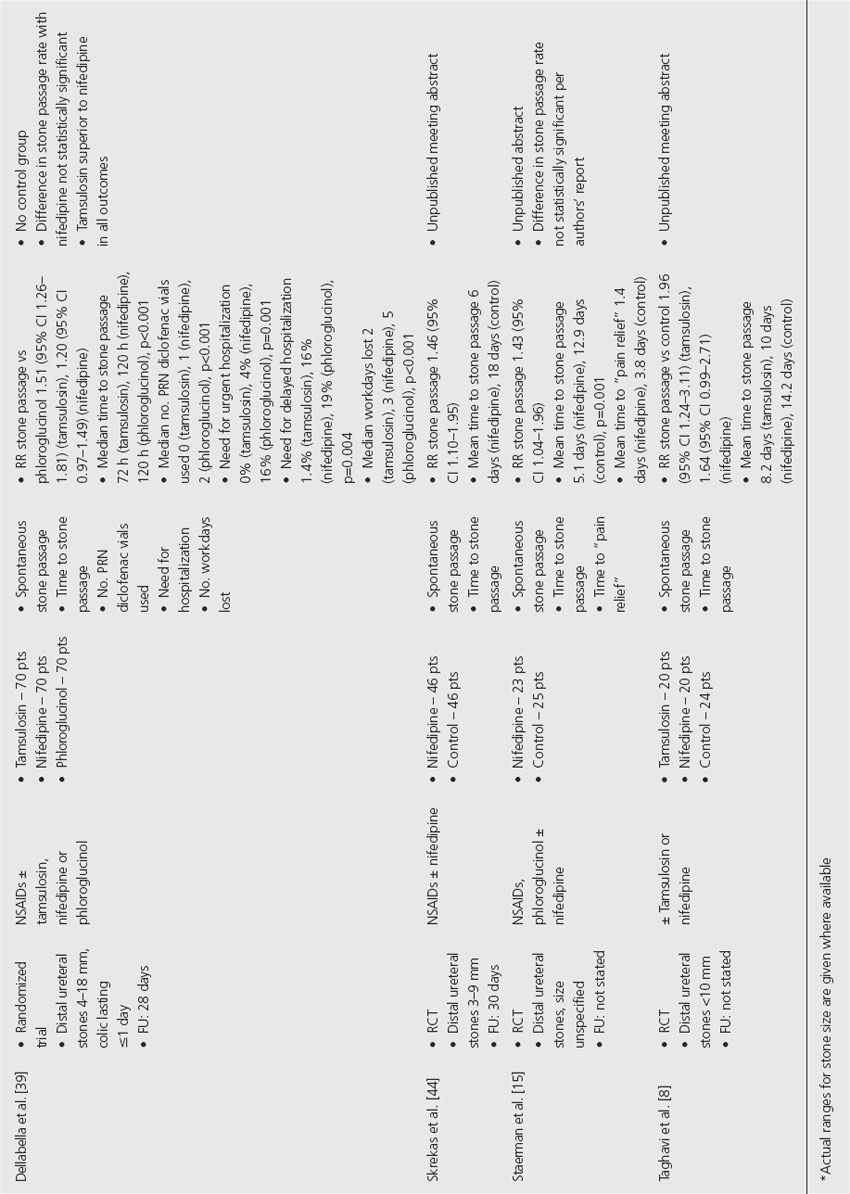

All eight RCTs using calcium channel antagonists as initial MET used nifedipine. Three trials utilized nifedipine in conjunction with other medications including glucocorticoids, antibiotics, and acetaminophen (Table 22.2). Three studies were performed with a tamsulosin arm as well. Most trials examined patients with distal ureteral stones that ranged in size up to 18 mm. One study did not specify the size of the stones and one did not specify location in the ureter. None of the studies included patients who had undergone previous shock-wave lithotripsy or prior MET. Follow-up, which was stated for all but two studies, was performed between 28 and 45 days.

Spontaneous stone passage rates for nifedipine ranged from 75% to 91%, with the overall stone passage rate being 81%. Spontaneous stone passage rates for controls in these studies ranged from 35% to 64%, with the overall stone passage rate being 58%. The RR for stone passage with nifedipine versus controls ranged from 1.20 to 2.24, with an overall RR of 1.52 (95% CI 1.35–1.71). Mean time to stone passage was generally shorter for nifedipine arms (5.0–12.2 days) compared to controls (5.0–20.0 days). Porpiglia et al. found a statistically decreased analgesic requirement with nifedipine [16]. Additionally, Cooper et al. found a statistically significant decrease in the number of workdays lost with nifedipine [17].

Although relatively well tolerated, nifedipine usage was associated with adverse reactions resulting in discontinuation of treatment in a small number of patients. Nifedipine usage was also associated with an up to 21% incidence of minor side effects including headache, palpitations, asthenia, and stomach ache [16]. In each of the three studies that compared nifedipine to tamsulosin, tamsulosin was superior in spontaneous stone passage rates and time to stone passage.

Comment

The evidence for MET for distal ureteral stones using calcium channel antagonists is of moderate quality. The evidence suggests that nifedipine can improve spontaneous stone passage rates and time to stone passage. However, it does appear to be associated with an increased risk of minor side effects as well as a small risk of adverse reactions leading to discontinuation of therapy. Furthermore, in all studies in which nifedipine and tamsulosin were compared, nifedipine was the inferior treatment option. In light of the superior efficacy of alpha-adrenergic antagonists and their relatively more benign side effect profile, the recommendation to use a calcium channel antagonist as MET for ureteral stones is weak. However, in the setting of a patient who cannot tolerate alpha-adrenergic antagonists, a strong recommendation to use calcium channel antagonists can be made based upon moderate-quality evidence (Grade 1B).

Clinical question 22.3

What is the effect of corticosteroid therapy on expulsion of ureteral stones?

Literature search

The PubMed literature search used above yielded one RCT that specifically studied the use of a corticosteroid in MET for distal ureteral stones. Searches of CINAHL and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials did not identify any additional published randomized studies. A search of EAU online meeting abstracts identified two additional unpublished trials. A search of AUA online meeting abstracts did not yield any additional studies.

The evidence

Table 22.2 Effect of calcium channel antagonists on ureteral stone passage

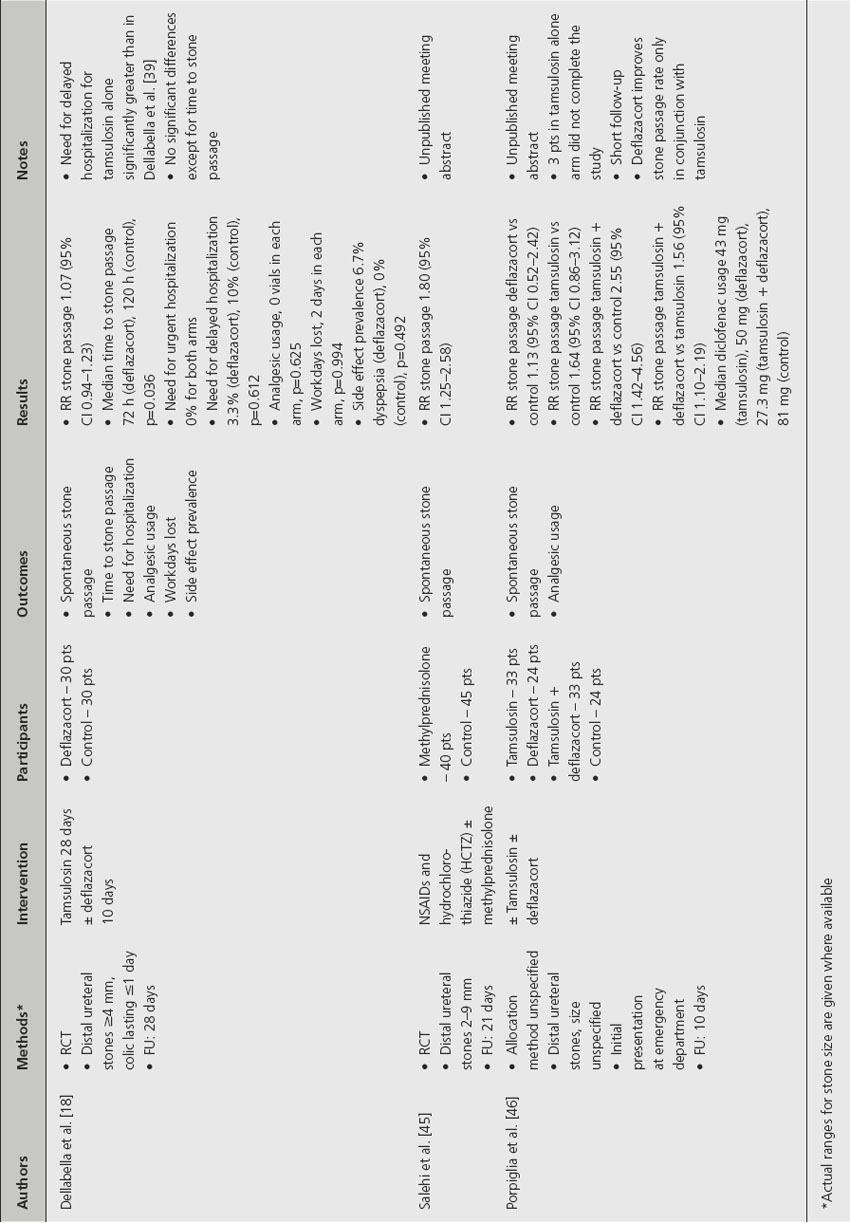

Of the three trials studying corticosteroid treatment for MET of distal ureteral stones, two used deflazacort and one used methylprednisolone (Table 22.3). These trials examined patients with distal ureteral stones that were2–9 mm in size, ≥ 4 mm in size or size unspecified. Follow-up ranged from 10 to 28 days. Two of the studies examined the use of a corticosteroid in conjunction with tamsulosin. The spontaneous stone passage rate with corticosteroid treatment alone ranged from 38% to 80% versus 33% to 44% with controls. When tamsulosin was given in addition to a corticosteroid, the stone passage rates ranged from 85% to 97% compared to 55% to 90% without the corticosteroid. The RR of stone passage with a corticosteroid alone versus controls ranged from 1.13 to 1.80 with an overall RR of 1.60 (95% CI 1.15–2.22). The RR of stone passage for a corticosteroid with tamsulosin versus tamsulosin alone ranged from 1.07 to 1.71 with an overall RR of 1.27 (95% CI 1.07–1.50). In these limited studies, need for hospitalization, analgesic usage, and workdays lost were not significantly different between treatment arms. Dellabella et al. found that two out of 30 patients (7%) receiving deflazacort developed dyspepsia as a side effect [18].

Table 22.3 Effect of corticosteroids on ureteral stone passage

Comment

The evidence for MET for distal ureteral stones using corticosteroids is of low quality. Efficacy rates among studies varied widely and statistically significant differences between intervention and control arms were seen primarily in conjunction with an alpha-adrenergic antagonist. Although corticosteroids have been used in multiple studies as adjuncts to alpha-adrenergic antagonists and calcium channel antagonists for MET, no recommendation to use corticosteroids in this setting can be made and this issue will require further study.

Clinical question 22.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree