, Ivan Damjanov1 and Ryan M. Taylor2

(1)

University of Kansas School of Medicine, University of Kansas, Kansas City, KS, USA

(2)

Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, KS, USA

Acute Viral Hepatitis

Unless specified otherwise, the term acute viral hepatitis is used to denote liver infection with hepatotropic viruses A, B, C, D, and E. The disease is usually diagnosed serologically and the biopsy is seldom indicated except in atypical cases.

PATHOLOGY. The viral infection causes reversible and irreversible hepatocellular injury associated with a predominantly lobular inflammation, repair and regeneration. The most prominent consequence of these changes is a loss of normal lobular architecture commonly known as lobular disarray (Fig. 1).

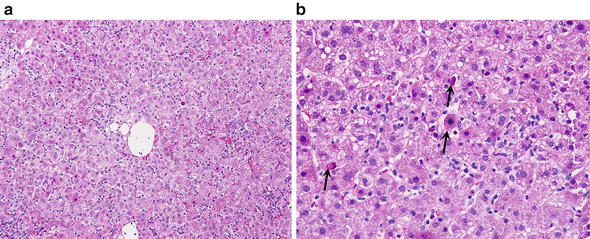

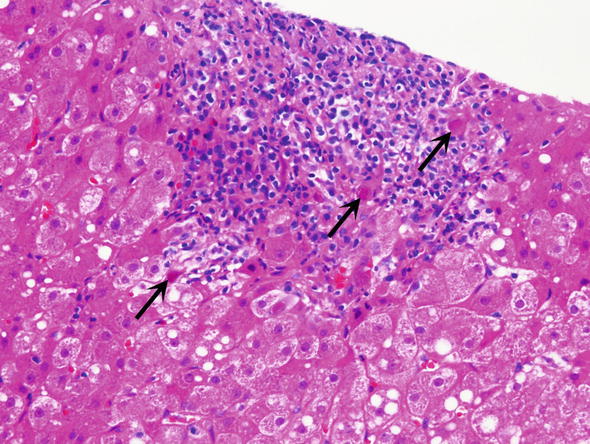

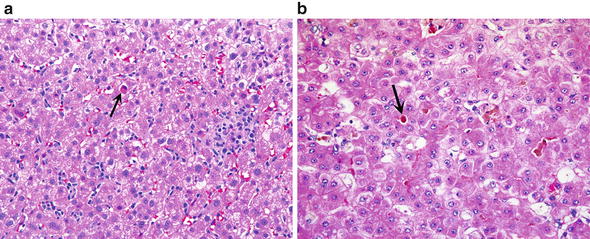

Fig. 1.

Acute viral hepatitis B. (a) Acute hepatitis is characterized by lobular disarray with swollen hepatocytes, apoptotic hepatocytes, sinusoidal and lobular lymphocytosis, and hyperplastic Kupffer cells. (b) The lobule shows several apoptotic bodies (arrows) scattered vacuolated cells, prominent Kupffer cells and some lymphocytes

The principal microscopic features of acute hepatitis include the following:

Vacuolar (“hydropic”) swelling of hepatocytes

Apoptosis of hepatocytes

Spotty lytic necrosis of hepatocytes marked by their dropout and replacement by aggregates of mononuclear inflammatory cells

Canalicular cholestasis, focal, mostly in zone 3

Regeneration of hepatocytes which are in mitosis or form 2–3 cell thick plates or rosettes (“pseudoglands”)

Hyperplasia of Kupffer cells with prominence of their cytoplasm containing PAS+/diastase resistant granules

Scattered inflammatory cells in the lobules—mostly lymphocytes, some plasma cells, and occasional eosinophils or neutrophils

Variant Forms

Several variant forms are recognized, of which we are listing three most important ones as follows:

∎ Acute cholestatic hepatitis. This form of acute hepatitis is characterized by inflammation accompanied by marked canalicular cholestasis. It may also involve the portal tracts, which show ductular reaction and even ductular cholestasis. Acute hepatitis A has a relapsing variant characterized by severe cholestasis.

∎ Massive/submassive necrosis. This rare form of hepatitis presenting as fulminant hepatic failure is characterized by extensive hepatocellular necrosis, which begins in centrilobular zone 3 but may spread to zone 2 and even zone 1.

∎ Resolving acute viral hepatitis. The biopsy of patients who are recovering from acute viral hepatitis may show mild lobular disarray or cholestasis. Aggregates of Kupffer cells may be prominent and may resemble granulomas.

Differential Diagnosis

Chronic viral hepatitis

Drug induced hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis

Infectious hepatitis of other kind (e.g., atypical viral or bacterial)

Wilson disease

Infiltrative malignancy such as lymphoma or leukemia

Comments

1.

Acute viral hepatitis in immunosuppressed persons and in pregnant women may be caused by herpes simplex virus. The infected liver shows focal areas of necrosis. Nuclei of infected cells contain viral inclusions which can be also highlighted by immunohistochemistry with virus specific antibodies. This presentation is characterized by an “anicteric hepatitis” with markedly elevated AST and ALT with relatively low serum bilirubin levels.

2.

Cytomegalovirus may infect both immunosuppressed and immunocompetent persons. In transplanted liver the CMV causes aggregates of neutrophils (“microabscesses”) or focal mononuclear infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages in the lobules or portal areas (Fig. 2). Viral inclusions can be seen in routine slides in the nuclei and also can be highlighted with specific antibodies immunohistochemically (Fig. 3).

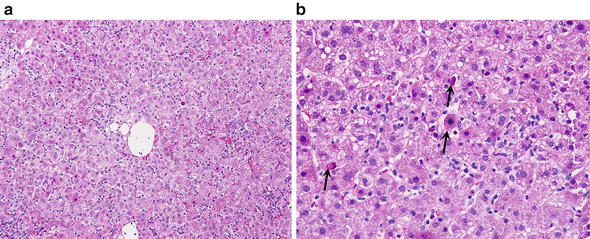

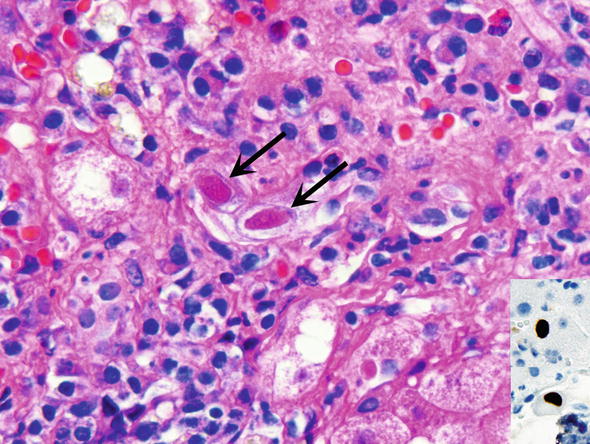

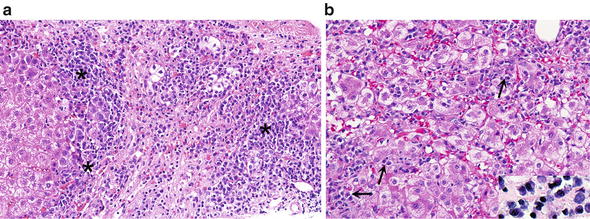

Fig. 2.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Within the area of portal inflammation one may see cells with CMV inclusions, which appear as dark red intra-nuclear inclusions (arrows)

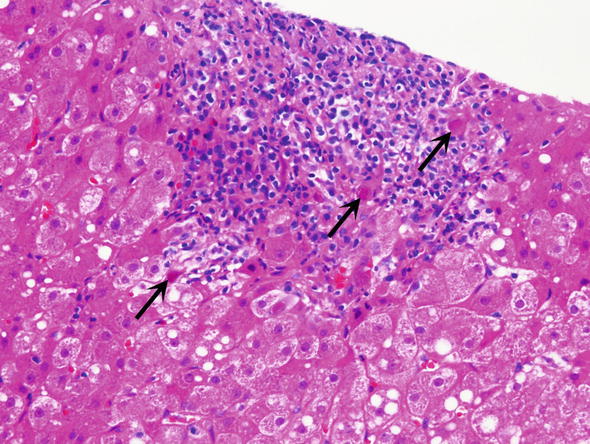

Fig. 3.

Cytomegalovirus infection. CMV inclusions are dark red (magenta) inclusions (arrows) surrounded by a clear halo (“owl eye”). Inset Immunohistochemistry with antibodies specific to CMV is useful for the definitive diagnosis, as shown in the inset as brown staining of the nuclei

3.

Epstein-Barr virus causes infectious mononucleosis of the liver. In the liver biopsy it typically presents with prominent accumulation of lymphocytes in the sinusoids and variable portal lymphocytosis.

4.

Viruses causing hemorrhagic fever, such as Ebola, Lassa or Marburg fever viruses cause acute hepatitis. Liver biopsy shows focal liver cell necrosis and apoptosis and very mild portal inflammation (Geller and Petrovic 2009).

Chronic Viral Hepatitis

Chronic viral hepatitis is defined as infection with hepatotropic viruses lasting more than 6 months. It occurs in approximately 80–85 % of patients infected with HCV, 5 % of those infected with HBV in the United States, and in up to 70 % those superinfected with HDV. Recurrence of infection has historically been very common in the setting of liver transplantation.

∎ PATHOLOGY. This viral infection is characterized by persistent portal chronic inflammation, associated to a variable degree with interface or lobular inflammation, hepatocellular injury, loss and regeneration, and portal and/or lobular fibrosis, capable of progressing to cirrhosis.

The principal microscopic features of chronic hepatitis include the following:

Portal tract infiltrates of lymphocytes, which may even form germinal follicles (Fig. 4)

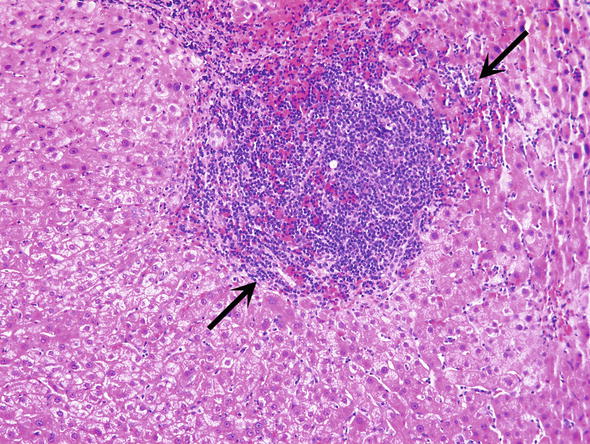

Fig. 4.

Chronic viral hepatitis C. Infiltrates of lymphocytes are expanding the in the portal tract (arrows)

Interface hepatitis disrupting the limiting plate and causing hepatocyte injury in zone 1 (variable)

Apoptosis of hepatocytes (Fig. 5a)

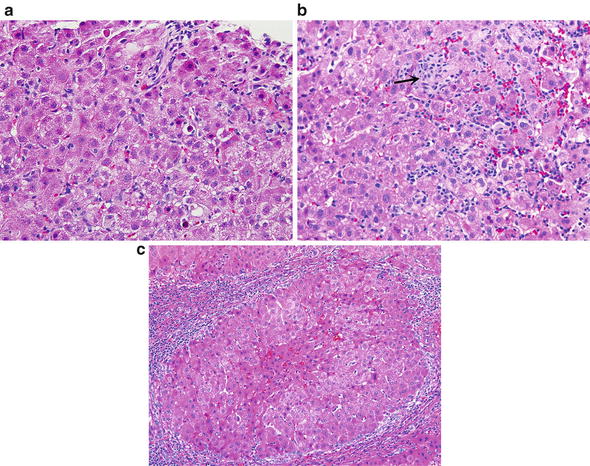

Fig. 5.

Chronic viral hepatitis C. (a) Lobules show slight disarray and contain scattered apoptotic bodies, some vacuolated hepatocytes, prominent Kupffer cells, and lymphocytes. (b) More prominent lobular inflammation with vacuolization of hepatocytes, prominent Kupffer cells and lymphocytes. Groups of macrophages/Kupffer cells aggregate at the site of hepatocyte loss (arrow). (c) Cirrhosis is characterized by formation of parenchymal nodules of hepatocytes completely surrounded by fibrous bands. The fibrous strands are infiltrated with lymphocytes

Kupffer cell and mononuclear cell aggregates around damaged and or dying hepatocytes (Fig. 5b)

Regenerating hepatocyte forming 2–3 cell thick plates or rosettes

Macrovesicular steatosis (most prominent in infection with HCV genotype 3)

Fibrosis (variable), progressing from portal areas into lobules resulting in portal-portal and portal-central bridging fibrosis or progressing to cirrhosis (Fig. 5c)

Variant Forms

∎ Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis C and B. This uncommon form of chronic hepatitis is typically seen in liver transplants and immunosuppressed persons. In addition to cholestasis it is characterized by portal fibrosis extending in a pericellular pattern into the lobules. Bile ductular proliferation is present and could be confused with changes caused by biliary obstruction. This variant is becoming less common with the utilization of highly effective treatments for hepatitis B and hepatitis C.

∎ Chronic hepatitis C and autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome. Coexistence of HCV infection and autoimmune hepatitis may cause diagnostic problems. Microscopically, the infiltrates in the portal tracts contain prominent plasma cells and the inflammation often extends into the lobule. It may also present with bridging and panacinar necrosis, which are uncommon in typical chronic HCV (Torbenson 2015).

Differential Diagnosis

Autoimmune hepatitis

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Drug induced hepatitis

Wilson disease

α1-Antitrypsin deficiency

Comments

1.

Antibodies to HBV surface and core antigen can be used to demonstrate HBV infection immunohistochemically. There is no reliable immunohistochemical method for HCV. However, laboratory serologic tests and other viral quantification methods are extremely reliable for confirmatory diagnosis if needed.

2.

Grading of the inflammatory activity and staging of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis may be performed using various semiquantitative systems, such as those developed by Ishak et al. (1995), or Batts and Ludwig (1995) (Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 6 and 7).

Table 1.

Batts-Ludwig system for grading of chronic hepatitis

Numerical grade | Descriptive grade | Interface activity | Lobular activity |

|---|---|---|---|

0 | Portal inflammation only | None | None |

1 | Minimal | Minimal, patchy | Minimal; occasional hepatocyte apoptosis |

2 | Mild | Mild; may involve some or all portal tracts | Mild; minimal, barely visible hepatocyte injury |

3 | Moderate | Moderate; involves all portal tracts | Moderate; focal hepatocyte injury readily identified |

4 | Severe | Severe; may have bridging necrosis | Severe; prominent diffuse hepatocyte injury |

Table 2.

Batts-Ludwig system for staging of chronic hepatitis

Numerical stage | Descriptive stage | Microscopic findings |

|---|---|---|

0 | No fibrosis | Normal portal tracts |

1 | Portal fibrosis | Fibrous portal tract expansion |

2 | Periportal fibrosis | Fibrosis extending between periportal hepatocytes or forming rare portal-portal septa |

3 | Septal fibrosis | Fibrous septa with distortion of lobular architecture; no definitive evidence of cirrhosis |

4 | Cirrhosis | Cirrhosis |

Fig. 6.

Batts-Ludwig system for grading of necroinflammatory activity in chronic hepatitis. 0—chronic hepatitis with no activity (“inactive hepatitis”). Grade 1 minimal interface activity, grade 2 mild interface activity, grade 3 moderate interface activity, and grade 4 severe interface activity with confluent necrosis. Adapted with the permission of first author from Batts KP, Ludwig J. Chronic hepatitis. An update on terminology and reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1409–17

Fig. 7.

Batts-Ludwig system for staging of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis. (a) Portal tract scarring, with no extension into the lobule, corresponding to stage 1. (b) Strands of fibrosis extending from the portal tracts into the lobule with an occasional portal to portal septum, corresponding to stage 2. (c) Fibrosis with bridging fibrosis in transition to cirrhosis, corresponding to stage 3. (d) Irregular regenerating nodules surrounded by thick fibrous strands, corresponding to cirrhosis, which is stage 4. Adapted with the permission of first author from Batts KP, Ludwig J. Chronic hepatitis. An update on terminology and reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1409–17

Drug Induced Liver Injury

Drug induced liver injury (DILI) is a common cause of acute liver injury or dysfunction. It may be classified as predictable dose related, immune mediated hypersensitivity type, or unpredictable idiosyncratic DILI. Liver injury may present in many patterns.

∎ PATHOLOGY. There are no diagnostic findings defining DILI, and the diagnosis is usually established by correlating the pathologic and clinical findings, and by excluding other liver diseases by means of laboratory tests.

Several histopathologic patterns of DILI can be recognized as follows:

Acute viral hepatitis like lobular inflammation (Fig. 8a)

Fig. 8.

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI). (a) In this hepatitis-like form of DILI the lobule shows disarray and is infiltrated with lymphocytes. There are occasional apoptotic cells (arrow), and infiltrates of macrophages and lymphocytes. (b) DILI shown here shows hepatocyte rosette formation with canalicular cholestasis (arrow). Other features seen in this picture are scattered lobular inflammatory cells and variably stained hepatocytes.

Bland cholestasis (Fig. 8b)

Submassive or massive necrosis evolving usually from zonal necrosis

Chronic hepatitis like predominantly portal inflammation, occasionally combined with lymphocytic cholangitis

Ductopenic portal fibrosis

Granulomatous hepatitis

Steatosis, which is most often macrovesicular but in some instances may be microvesicular or mixed

Steatohepatitis

Fibrosis, which may be portal, periportal or pericellular

Vascular congestions and sinusoidal dilatation

Differential Diagnosis

Acute or chronic viral hepatitis

Autoimmune liver diseases

Granulomatous hepatitis (e.g., sarcoidosis)

Steatohepatitis

Cholangitis (PBC, PSC or biliary infection)

Comments

1.

In 90 % of cases DILI presents clinically as acute hepatitis with elevation of transaminases with or without elevation of alkaline phosphatase (Le Bail et al. 2015). Significant elevation of bilirubin in DILI is considered a poor prognostic marker.

2.

Bland cholestasis with minimal inflammation is most often a feature of DILI.

3.

Centrolobular coagulation necrosis sharply demarcated from preserved hepatocytes is a common feature of acetaminophen poisoning, the most common form of drug toxicity.

4.

Mild portal inflammatory infiltrates which contain neutrophils and eosinophils are a found in hypersensitivity reactions.

5.

Finding of granulomas should always include DILI in the differential diagnosis, even though most liver granulomas are not related to drug ingestion.

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an immune mediated chronic hepatitis, predominantly affecting women. It is associated with hypergammaglobulinemia, diagnostic elevation of autoantibodies to nuclear antigens (ANA), smooth muscle actin (ASMA) or liver-kidney microsomes (anti-LKM). The disease may progress to cirrhosis but generally it has a good response to corticosteroid treatment and immunomodulator treatments. Clinical scoring system is useful for establishing the diagnosis and assessing the activity of the disease (Batts 2015).

∎ PATHOLOGY. Microscopic changes vary and depend on the activity of the disease, its duration and response to treatment.

The principal microscopic features of AIH include the following:

Portal infiltrates composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 9a)

Fig. 9.

Autoimmune hepatitis. (a) An intense lymphocytic and plasmacytic infiltrate (asterisks) characterizes most liver biopsies of autoimmune hepatitis. (b) Lobular disarray with infiltrates of lymphocytes and plasma cells which can be readily identified (arrows). Inset shows plasma cells with eccentric round nuclei, bluish cytoplasm and some perinuclear clearing

As notorious as the association is between plasma cells and AIH, it is worth knowing that about 20 % of cases of AIH can have few or no plasma cells, so their absence does not preclude a diagnosis of AIH

Interface hepatitis with periportal damaged hepatocytes surrounded by lymphocytes and plasma cells

Lobular cholestasis with hepatocyte rosettes

Lobular hepatitis with intralobular plasma cells and lymphocytes (Fig. 9b)

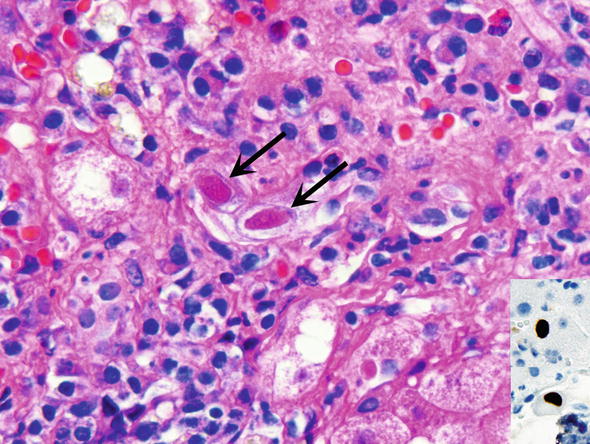

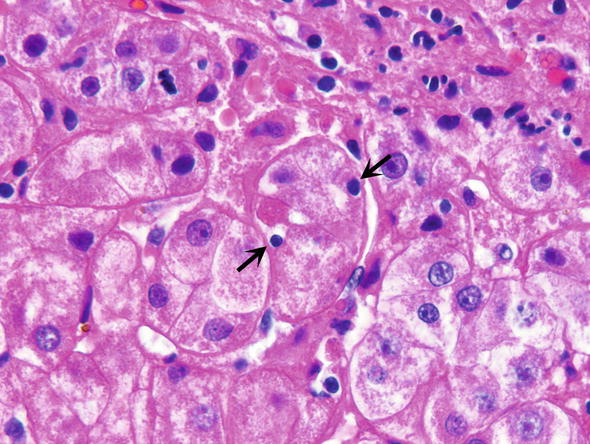

Emperipolesis, i.e., invagination of lymphocytes into the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (Fig. 10)

Fig. 10.

Autoimmune hepatitis. Emperipolesis refers to lymphocytes included or invaginated into the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (arrows). The affected hepatocytes form a rosette, which is a response to cholestasis that occurs in autoimmune hepatitis

Scattered hepatocyte injury including hydropic change, apoptosis and foci of necrosis

Lobular disarray with anisocytosis and regeneration of hepatocytes

Intralobular necrosis which may be confluent (in severe fulminant AIH, and very active cases)

Progressive fibrosis spreading from the portal tracts into the lobules ending in cirrhosis in drug resistant or untreated cases

Variant Forms

Several variant forms are recognized of which we are discussing only the most important ones as follows:

∎ Acute onset AIH. The disease resembles acute viral hepatitis, and may also resemble drug induced hepatitis. Serologic findings can be helpful for the correct diagnosis although sometimes these cases can be challenging to diagnose.

∎ Fulminant form of AIH with submassive necrosis. This rare form of AIH must be distinguished from fulminant viral hepatitis and drug related massive necrosis, as in acetaminophen poisoning.

∎ Chronic AIH. This form of AIH shows active lobular and interface hepatitis which is rarely seen in chronic HCV. However such inflammatory activity may be seen in some patients with chronic HBV (Batts 2015). Serologic and virologic tests are important for the right diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree