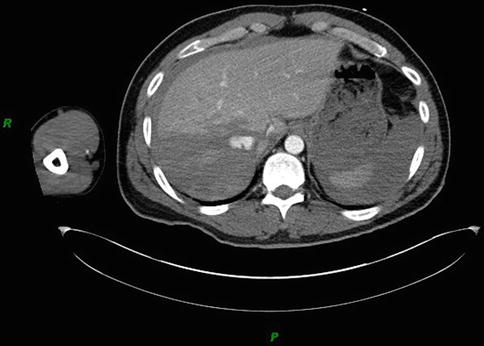

Fig. 4.1

Positive FAST showing fluid in the hepatorenal space

In patients with penetrating trauma, FAST is less sensitive, and a negative FAST should not be used as the sole criterion to determine need for and urgency of intervention [2]. Gunshot wounds with peritoneal traverse are associated with an extremely high probability of resulting in an injury that requires surgical intervention and the same consideration applies to missile injuries that traverse the upper abdominal quadrants with respect to liver injuries. Stab wounds are associated with a significantly lower probability of intra-abdominal injury, but the presence of shock, signs of peritoneal irritation, or a positive FAST confirms penetration of the peritoneal cavity and high likelihood of intra-abdominal injury requiring surgical intervention.

After ascertaining that there is ongoing intra-abdominal hemorrhage, patients with penetrating abdominal trauma must be transported to the operating room without delay. In these patients, delaying massive fluid resuscitation prior to definitive control of bleeding may improve survival [3]. They are better served by intubation and placement of large-bore vascular access and arterial line by the anesthesiology team in the operating table while the surgical team is assembling for surgical control of hemorrhage.

In the blunt trauma patient with associated significant traumatic brain injury, however, resuscitation to a systolic blood pressure above 90 mmHg is more important, in order to preserve cerebral blood flow and avoid the potential for secondary brain injury associated with hypotension.

In the patient with penetrating torso trauma who loses detectable blood pressure and/or pulses within few minutes of presentation, immediate left anterolateral thoracotomy should be carried out in the emergency department concurrent with orotracheal intubation [4]. After open cardiac massage and addressing the intrathoracic injuries, if there is an organized cardiac rhythm, we favor cross clamping the descending thoracic aorta to minimize abdominal blood loss before proceeding to the operating room. In the patient with blunt trauma who loses blood pressure and/or pulses within few minutes of presentation, ED resuscitative thoracotomy in the emergency room is generally discouraged because of the dismal survival rate, but there have been rare survivors [5].

Assessing Need for Further Radiologic Imaging

The decision to obtain a CT depends on the mechanism of injury, the response to initial fluid resuscitation, and the surgeon’s judgment of whether or not information gained from CT would be useful or would alter the management plan.

In the hemodynamically normal patient with a gunshot wound on physical examination, if estimation of trajectory on biplanar plain radiographs suggest peritoneal traverse and there is no evidence of intrathoracic or spinal injury, a preoperative CT is usually not required or helpful. As mentioned before, a negative FAST does not rule out active hemorrhage. In the hemodynamically normal patient with a suspected tangential trajectory, CT may give enough information to the surgeon to avoid laparotomy. In the hemodynamically normal patient with a transmediastinal trajectory or a suspected thoracic vascular injury, CT scanning may also be helpful.

In the blunt trauma patient with a positive FAST, the decision to obtain a CT scan is based on the response to initial fluid resuscitation. Although the imaging time has been reduced with the new generation of multi-detector spiral CT scans to the point of being insignificant, the time and effort required to transport and position the patient remains unchanged and is long enough that the patient may deteriorate with resulting increased morbidity and mortality (Fig. 4.2). If there is suspicion of ongoing bleeding based on information gathered in the trauma room, it is important that a trauma team member continues to direct the resuscitation process in CT. While not a widespread practice, quick bedside estimation of the degree of hemoperitoneum on FAST can be a useful adjunct for the surgeon to decide if there is a need to rapidly transport a patient to the operating room without CT (Table 4.1) [6, 7].

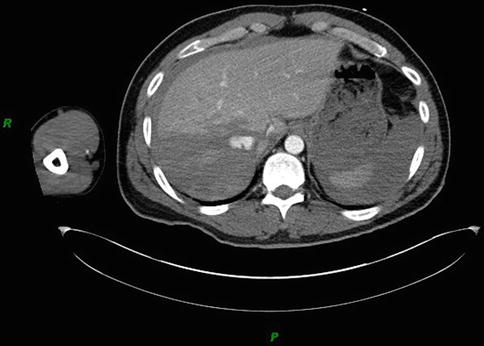

Fig. 4.2

CT showing active liver bleeding with intravenous contrast extravasation and hemoperitoneum. Patient became hypotensive requiring laparotomy shortly after the CT. Bleeding was controlled intraoperatively and no further therapeutic adjunctive measurers were needed

Table 4.1

Estimation of hemoperitoneum

Location of blood | Estimated blood volume (ml) |

|---|---|

1. Morrison’s pouch and/or splenorenal space | 150 |

2. 1 + pelvic cavity | 400 |

3. 2 + left subphrenic space | 600 |

4. 3 + bilateral paracolic gutters | 800 |

5. 4 + right anterior subphrenic space | |

Thickness of fluid at right anterior subphrenic space

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|