Fig. 21.1

(a) Standard lymph node dissection for prostate cancer includes the lymph nodes adjacent to the external iliac vein and the obturator fossa, extending from the node of Cloquet to the confluence of the external and internal iliac veins. (b) Extended lymph node dissection includes the standard template and the nodes adjacent to the internal iliac vein and common iliac vessels up to the ureter

Since the emergence of robotic prostatectomy (RARP), its oncologic efficacy relative to open prostatectomy (RRP) has been debated. In a recent meta-analysis of robotic prostatectomy, 13 series that compared RARP (3,917) to RRP (4,241) demonstrated no difference in positive surgical margins (847 and 820 cases for each, HR = 1.2, p = 0.19) [7]. There was also no difference in biochemical recurrence between RARP and RRP (HR = 0.9, p = 0.53). Positive margins were also similar for laparoscopic prostatectomies. In a separate meta-analysis, urinary incontinence was slightly less for RARP (7.5 %) than RRP (11.9 %) at 12 months (HR = 1.53, CI95 % = 1.04–2.53) [8]. Finally, the same authors performed a meta-analysis evaluating potency rates following RARP and RRP, demonstrating a slight advantage at 12 months with RARP (OR: 2.84, CI95 %: 1.46–5.43) [9]. Though slight advantages were seen for functional outcomes, true comparison of technique was limited in these meta-analyses, given wide variation in patients, outcome definitions and reporting.

21.3 Bladder Cancer

Though bladder cancer is discussed in other chapters, several crucial aspects regarding its management are still debated. The therapeutic effect of lymphadenectomy and the extent is one such topic. Another is the comparison between open and laparoscopic or robotic cystectomy. Finally, the benefit and timing of perioperative chemotherapy is debated.

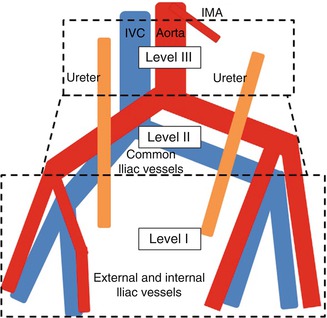

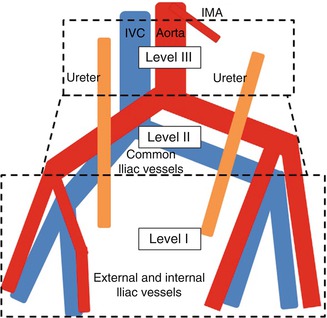

In patients undergoing radical cystectomy, 25–30 % were found to have positive lymph nodes [10–12]. Along with grade and stage at transurethral resection, the presence of lymphovascular invasion and preoperative hydronephrosis predicted lymph node metastasis [13–15]. Many series have attempted to delineate a minimum number of nodes as measure of extent, ranging from 10 to 16 [16]. However, one large series showed increasing survival benefit with increasing node counts [17]. Additionally, lymph node counts are affected by patient anatomy, and specimen collection, processing, and interpretation [18]. Lymph node extent was better defined by template, which can be divided into three levels (Fig. 21.2). Rates of node positive ranged from 21 to 31 % for level I, 9 to 19 % for level II, and 7 to 13 % for level III [19–21]. Additionally, the necessary extent for lymph node dissection was affected by the rate of skip metastases observed which range from 2 to 8 % of cases with positive nodes in level II [12, 20, 22], and 0–6 % for level III [20, 21], though many series have found the latter to be rare. While an extended lymphadenectomy versus a limited dissection (approximating level 1) has shown improved survival [11, 23], a recent comparison of superextended up to the inferior mesenteric artery (level III) showed no benefit over lymphadenectomy up to the proximal common iliac arteries (level II) [24]. The survival benefit of extended lymphadenectomy is also clouded by stage migration.

Fig. 21.2

Three levels of template dissection relevant to bladder cancer. Level 1: external iliac nodes, internal iliac nodes, obturator, and deep obturator nodes. Level 2: Common iliac, presacral and presciatic nodes. Level 3: Para-aortic, interaortocaval, and paracaval lymph nodes below the inferior mesenteric artery

Systemic chemotherapy has also been shown to improve survival in patients undergoing radical cystectomy. In the neoadjuvant setting, a randomized trial comparing 153 treated with MVAC versus 154 without chemotherapy showed a median survival benefit of 77 months vs 46 months (p = 0.05) [25]. In terms of cancer specific survival, there were 54 deaths due to bladder cancer in the neoadjuvant group and 77 in the group treated with surgery alone, HR = 1.66 (CI95 %: 1.22–2.45). Similarly, a meta-analysis of 11 trials comparing platinum based neoadjuvant chemotherapy with surgery alone demonstrated a benefit in overall survival (HR: 0.86, CI95 %: 0.77–0.95) [26]. In the adjuvant setting, Svatek et al. retrospectively reviewed 3,947 patients from 11 different institutions, finding improved survival with adjuvant chemotherapy (HR: 0.83, CI95 %: 0.72–0.97 %) [27]. Direct comparison of neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus adjuvant chemotherapy is inadequate in the current literature. However, Eldefrawy et al. demonstrated that patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy were more likely to complete the planned cycles of chemotherapy (83.5 %) than those receiving adjuvant chemotherapy (35.5 %) [28]. The reason for this may be due to the difficult recovery that is required following radical cystectomy with urinary diversion.

Through increased robotic experience, many institutions have performed minimally invasive radical cystectomies with lymph node dissection. Several series demonstrated similar oncologic efficacy and complications between robotic and open cystectomy with less blood loss at the expense of typically longer operative times (Table 21.1) [29–34]. Lymph node yield and the proportion of cases with positive lymph nodes were similar for both modalities. Type of urinary diversion did not vary, though it is not clear what proportion were performed by an intracorporeal method.

Table 21.1

Comparison of the outcomes of robotic and open cystectomy

N | EBL(ml)/transfuse % | OR time | Complications % | LOS d | Positive margin % | LN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nix et al. [29] | RC- 21 | 258a | 4.2a | 33 | 5.1 | 0 | 18 (12–30) |

OC- 20 | 575 | 3.5 | 50 | 6.0 | 0 | 18 (8–30) | |

Parekh et al. [30] | RC- 20 | 400a/0 | 300a (245–366) | 20 (Cl >1) | 6 | 5 | 11 (9–21.5) |

OC- 20 | 800/2 | 285 (240–321) | 20 (Cl >1) | 6 | 5 | 23 (15–28) | |

Styn et al. [31] | RC- 50 | 350a/4a | 459 | 28.1 (Cl >2) | 9.5 | 2 | 14.3 ± 9.1 |

OC-100 | 475/24 | 349 | 21.3 (Cl >2) | 10.2 | 2 | 15.2 ± 9.5 | |

Knox et al. [32] | RC-58 | 276a | 7.8a ± 1.5 | 43 | 7 | ||

OC-84 | 1,522 | 6.6 ± 1.25 | 65 | 8 | |||

Gondo et al. [33] | RC-11 | 656a/0a | 54 | 9.1 | 20.6a | ||

OC-15 | 1,788/40 | 75 | 20 | 14.1 | |||

Nepple et al. [34] | RC-36 | 675a/39a | 410 | 7.9 | 6 | 17 (12–20) | |

OC-29 | 1,497/83 | 345 | 9.6 | 7 | 14 (10–20) |

21.4 Distal Ureteral Cancer

Upper tract urothelial-cell carcinoma accounts for 5 % of urothelial carcinomas [35]. Nearly 70 % of ureteral tumors occur in the distal ureter, which is found in the pelvis [35]. Radical nephroureterectomy is the gold standard treatment for high grade and invasive tumors of the upper tract. In a recent multi-institutional review of 1,363 patients, cancer-specific survival following nephroureterectomy was 78.3 ± 1.3 and 72.9 ± 1.4 % at 3 and 5 years respectively [36]. Imaging with CT urogram is the modality of choice for diagnosing distal ureteral tumors [37]. Cytology can be helpful as positive cytology has been associated with muscle-invasive and higher stage tumors [38]. Ureteroscopy is a useful diagnostic adjunct, when the diagnosis is uncertain, and it can determine tumor grade in 90 % of cases [39].

While nephroureterectomy is the gold standard therapy for invasive upper tract tumors, distal ureterectomy may have a similar outcome to nephroureterectomy in managing invasive or high grade tumors in the distal ureter. Initially performed for cases in which renal preservation was imperative (i.e., solitary kidney), distal ureterectomy is increasingly offered electively to reduce the development of chronic kidney disease, thereby avoiding associated cardiovascular morbidity and maximizing adjuvant chemotherapy options. Recently, several series demonstrated similar oncologic efficacy of segmental ureterectomy versus nephroureterectomy for distal ureteral tumors (Table 21.2) [40–45]. Follow-up of these patients demonstrated that recurrence in the ipsilateral upper tract was low. For example, Dalpiaz et al. noted two patients with such recurrence at 63 and 45 months after surgery, both were alive after nephroureterectomy [40]. When planning a distal ureterectomy, diagnostic ureteroscopy was avoided in several of the series for fear of seeding the proximal upper urinary tract. Additionally, performance of lymphadenectomy during nephroureterectomy or distal ureterectomy was done sparingly in many of the series [40, 41, 43]. Although lymphadenectomy is beneficial in bladder urothelial carcinoma, a similar benefit for upper tract urothelial cancer has not been definitively shown [46]. Furthermore, the precise boundaries for lymphadenectomy for upper tract TCC is not clearly defined. In the multi-institutional review, Margulis et al. found that lymphadenectomy was performed in 48 % of cases [36].

Table 21.2

Comparison of the oncologic outcomes of nephroureterectomy and distal ureterectomy for distal ureteral tumors

Series | Number of patients | Median follow-up(months) | Cancer-specificsurvival (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Dalpiaz et al. [40] | RNU: 42 | 51.5 | 5 years: 78 | 0.92 |

DU: 49 | 5 years: 77 | |||

Simonato et al. [41] | DU: 73 | 87 | 5 years: 94.1 | |

Colin et al. [43] | RNU: 416 | 26 | 5 years: 86.3 | 0.99 |

DU: 52 | 5 years: 87.9 | |||

Jeldres et al. [42] | RNU: 1,222 | 30 | 5 years: 82.2 | >0.05 |

DU: 569 | 5 years: 86.6 | |||

Lehmann et al. [44] | RNU: 91 | 96 | 10 year pTa/1: 87 | 0.271 |

DU: 51 | 10 year pT2-4: 36 | |||

Giannarini et al. [45] | RNU: 24 | 58 | 5 years: 66 | 0.896 |

DU: 19 | 5 years: 64 |

Although theoretical, the benefit of platinum-based chemotherapy was assumed due to the success of this regimen in bladder cancer, but there is considerably less data for its support for the treatment of upper tract TCC. In one study of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (which compared 43 patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy with 107 historical controls), Margulis et al. demonstrated a reduction in stage pT2 or higher disease (46.5 % versus 65.4 %) and pT3 or higher disease (27.9 % versus 47.7 %) at the time of surgery in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy [47]. In two separate multi-institutional studies, adjuvant chemotherapy had minimal impact on cancer-specific survival [48, 49].

Minimally invasive distal ureterectomy with reconstruction for distal ureteral cancer was reported in some series [50–54]. Schimpf et al. reported 11 patients, of which 5 were for ureteral cancer, with median operative time of 189 min [50]. One intraoperative complication, an iliac vein injury, was repaired intraoperatively. Three patients underwent psoas hitch and two underwent boari flap. There were two recurrences noted, both in the ipsilateral pelvis treated with nephroureterectomy. All patients were free of disease at follow-up. Glinianski et al. reported nine patients undergoing distal ureterectomy of which six had a psoas hitch, with a mean operative time was 252 min [51]. There were no intraoperative complications, and all margins were negative. One patient each had pT1,2, and 3 disease, and five patients had high grade urothelial carcinoma. During follow-up five patients had superficial bladder cancer, and one patient had superficial recurrence in the renal pelvis. In general patients undergoing distal ureterectomy by minimally invasive means tended to be of lower grade and stage. Robotic port placement was achieved with the camera cephalad to the umbilicus, with three trocars and one assistant port placed laterally in a configuration similar to robotic prostatectomy [50, 53].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree