Adverse consequences of kidney injury on hospital survival

In an Australian study of hospitalised patients identified by the RIFLE classification (Table 7.1), Uchino et al. (2010) demonstrated the serious consequences of either a transient (less than three-day) or more prolonged episode of AKI. Hospitalised patients who develop renal injury have a higher risk of death. Those with a transient rise in creatinine lasting less than three days had an inpatient mortality of 15%, and those with renal injury lasting greater than three days had an inpatient mortality of nearly 30%. Care could be improved by identifying at-risk individuals.

Risk factors for perioperative kidney injury

In the NCEPOD report Adding Insult to Injury: Reviewing the Care of Patients who Died in Hospital With a Primary Diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury (2009), the authors reviewed 976 adult cases from over 200 NHS hospitals in the UK who had died in a three-month period. They found that over 20% of patients who developed AKI and subsequently died had ‘forseeable and avoidable AKI’. Only 50% of patients were considered to have received a good standard of care. Failings were found in identification of ‘at-risk’ patients and in the management of AKI and its complications.

The care of patients at risk of AKI and of those with existing CKD can be improved by identifying them prior to problems arising. Opportunities to do this include:

- at the time of diagnosis of chronic medical conditions associated with CKD

- at the time of the prescription of medications that increase the risk of acute deterioration in kidney function with dehydration/hypovolaemia

- at the point of deciding to list for an operative procedure

- at pre-assessment for anaesthesia/operation

- at admission to hospital

- immediately preoperatively

Individuals who can be alerted to this increased risk include the patient, medical staff (including ward doctors, surgeons and anaesthetists) and nursing staff (including the pre-assessment clinic nurses, ward nurses, clinic nurses and theatre nurses). Patients who might be given specific warnings include those with pre-existing CKD, especially in the presence of other comorbidity such as heart failure or diabetes and those taking high-risk drugs including ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), direct renin inhibitors, diuretics, metformin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (see Chapter 8). Patients may need both verbal and written information, such as clinic letters and information sheets.

Patients identified as at increased risk should then receive enhanced care on admission to hospital, whether for planned or emergency treatment.

Surgical patients

Patients admitted to the surgical ward might be highlighted to the medical team for review, or specifically to the renal team for review. This should occur before any further deterioration in renal function in the hope of avoiding acute-on-chronic kidney injury, rather than after the event. Patients requiring an operation might need pre-optimisation, with transfer to either HDU or ICU preoperatively for optimisation of intravascular volume and cardiac output prior to surgery (Brienza et al. 2009). Patients likely to need HDU or ICU support postoperatively should have been identified prior to their operation. Patients who will be well enough to return to the general ward but who require enhanced surveillance can be identified to the critical care outreach team. Ward nurses should be made aware of the increased risk of kidney problems and the need for close monitoring and prompt reporting of any signs of deterioration.

Medical patients

Medical patients with or at risk of worsening renal injury should be highlighted to the renal team early in the course of their hospital admission. Critical care outreach, HDU and ICU should be involved early to pre-empt catastrophic deterioration on the general ward. Ward nurses caring for these patients must be made aware of the potential for deterioration and the action to take should this occur.

Key points

- AKI and acute-on-chronic kidney injury is often preventable.

- All staff involved in the patient’s care must be made aware of increased risk in certain patients, including ward nurses, critical care outreach, HDU and ICU.

- Renal teams should be alerted to high-risk patients when they are admitted to hospital for both elective and emergency procedures.

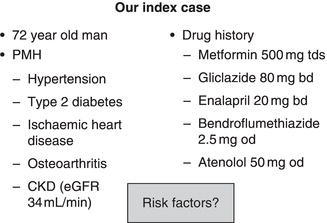

Our index case

Examine the index case (Figure 7.1). We will return to this gentleman later in the chapter, but for now assume that he has had an orthopaedic operation under spinal anaesthetic. Read through his details and try to identify all the factors that put him at high risk for AKI and the time points at which they could have been identified.

Impact of surgery on kidney function

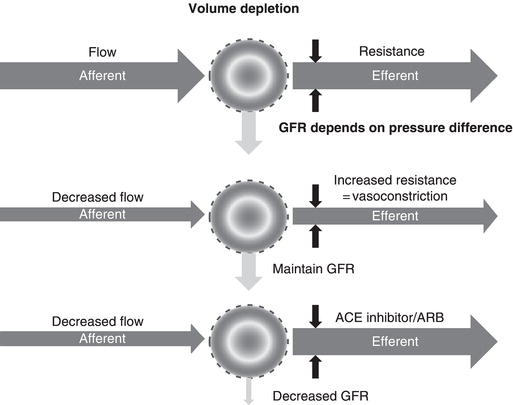

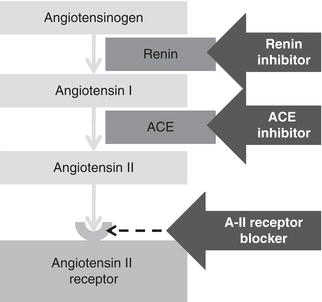

For the surgical patient the most important threat to the kidneys is a reduction in renal blood flow during the perioperative period. This may be due to either absolute (true) or relative hypovolaemia (Table 7.2). Absolute hypovolaemia reflects a decrease in absolute circulating volume. When blood volume falls, blood pressure is reduced and renal blood flow will fall. The normal response to a fall in renal blood flow is narrowing (constriction) of the post-glomerular efferent arteriole. This increases resistance to blood leaving the glomerulus and hence glomerular filtration is maintained (Figure 7.2). This efferent arteriolar constriction is dependent on angiotensin II, which is generated by the renin–angiotensin system (Figure 7.3). Angiotensinogen is cleaved by renin to form angiotensin I (blocked by renin inhibitors), which in turn is converted to angiotensin II by angiotensin converting enzyme (blocked by ACE inhibitors). Angiotensin II binds to angiotensin II receptors on the efferent arteriole, leading to vasoconstriction (blocked by angiotensin II receptor blockers, ARBs). Each of these groups of drugs will prevent the normal response to a fall in renal blood flow and so increase the risk of AKI if volume depletion occurs.

Volume depletion will be exacerbated by the use of diuretics, and hypotension by the use of other blood pressure lowering medication. Being ‘nil by mouth’ for a prolonged period of time will further exacerbate the risk of volume depletion.

Table 7.2 Causes of hypovolaemia.

| Absolute hypovolaemia | Relative hypovolaemia |

| Haemorrhage GI losses (diarrhoea/vomiting) Skin losses (burns) Renal losses (polyuria) | High cardiac output

|

Key points

- The commonest cause of AKI in surgical patients is hypovolaemia leading to reduction in glomerular perfusion.

- Drugs that interfere with the renin–angiotensin system will increase the risk of hypovolaemia-induced AKI.

Impact of CKD on standard protocols

Fluid management

Perioperative fluid regimes are designed to maintain euvolaemia. The traditional postoperative 3-litre fluid regime (typically 2 L of 5% dextrose/1 L of 0.9% sodium chloride) may need modifying in patients with kidney disease. In addition, the GIFTASUP recommendations (Powell-Tuck et al. 2006) need to be considered.

Daily fluid requirements need to be individualised to each patient. A patient recovering from kidney injury may be polyuric with a very high urine output and need several litres of fluid a day. An anuric dialysis-dependent patient may need less than 1000 mL of fluid per day. A patient with CKD may fall anywhere between these two extremes, and care needs to be taken to avoid giving too little fluid, leading to hypovolaemia and worsening pre-renal kidney injury, or giving too much fluid, leading to peripheral and pulmonary oedema.

The sodium content of fluid will also need to be individualised. 0.9% sodium chloride solution is actually hypertonic, containing 154 mmol sodium per litre. The more physiologically balanced fluids recommended in GIFTASUP have a lower sodium and chloride content (and therefore closer to physiologic). However, they also have a fixed potassium content. There is little published experience assessing their use in patients with acute, acute-on-chronic or chronic kidney disease, or in those with stage 5 CKD. Daily assessment of fluid balance must be based on clinical examination (pulse, blood pressure, jugular venous pressure), urine output, daily weight and input/output charts. Daily weights are the best guide to changes in water balance, but can sometimes be difficult to obtain in ill patients and do not distinguish between fluid in the vascular space and fluid in the interstitial space.

Particular care must be taken with the addition of potassium to intravenous fluid. Some intravenous crystalloid solutions have pre-added potassium (e.g. Hartmann’s solution contains 5 mmol/L potassium). Daily assessment of urea and electrolytes is essential.

Hyperkalaemia

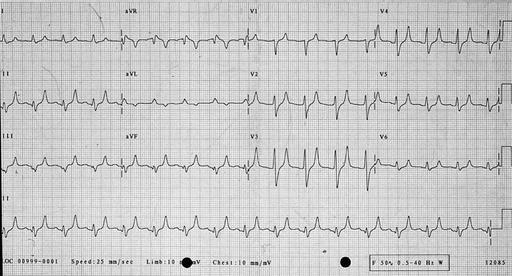

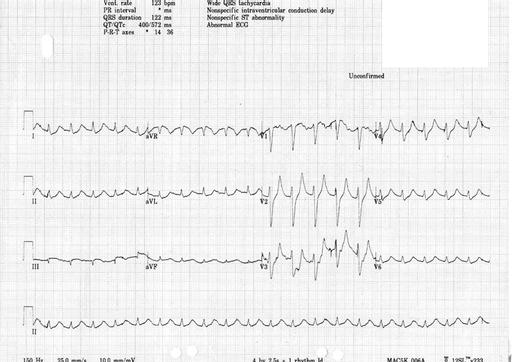

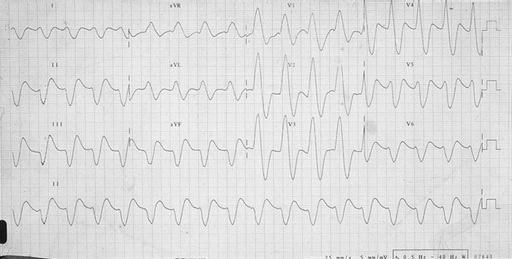

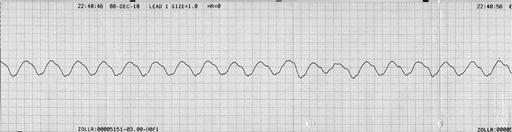

Potassium is renally excreted. Hyperkalaemia may cause symptoms such as palpitations, muscle weakness or paralysis. However, the first symptom may be life-threatening arrhythmia or cardiac arrest, and hyperkalaemia is one of the commonest causes of sudden death in patients with kidney failure. Hyperkalaemia may be suspected from the electrocardiogram before the serum potassium is available. Conversely, if serum potassium is > 6.5 mmol/L an ECG monitor should be attached to look for evidence of cardiac toxicity. Changes of hyperkalaemia include peaking of the T wave (Figure 7.4) , widening of the QRS complex (Figure 7.5), loss of the P wave (Figure 7.5), very broad QRS merging into the T wave (Figure 7.6) and a sine wave (Figure 7.7). If hyperkalaemia is suspected from the ECG, an arterial blood gas sample may allow a ‘quick’ result to guide urgent management.

Table 7.3 Causes of hyperkalaemia.

| Exogenous potassium administration | Potassium redistribution | Reduced potassium excretion |

| Oral potassium supplements (Food) Dioralyte Stored blood IV potassium Which intravenous fluid? | Insulin deficiency Starvation (nil by mouth) Beta-blockers Post-dialysis rebound | Volume depletion Spironolactone Amiloride ACE inhibitors Angiotensin II receptor blockers Beta-blockers NSAIDs Trimethoprim Heparin |

High potassium may be due to excessive potassium intake, potassium redistribution or reduced potassium excretion (Table 7.3). In contrast to popular belief, severe hyperkalaemia is rarely due to patient indiscretion, and advice to ‘stop eating bananas’ is rarely helpful. The management of acute severe hyperkalaemia is beyond the scope of this chapter.

Diabetes management

Many hospitals will use a standard prescription chart to manage patients with insulin-treated diabetes perioperatively. A typical regime includes 5% dextrose with potassium and soluble insulin (GKI). This regime may need altering in patients with impaired potassium excretion (omit potassium from the prescription) or who are fluid restricted (use a lower volume of a higher-concentration glucose solution, e.g. 500 mL of 10% dextrose in place of 1000 mL of 5% glucose).

Nutrition

Patients with acute, acute-on-chronic, chronic or end-stage kidney disease all have complex nutritional needs. They are frequently in a hypercatabolic state and are at high risk of malnutrition. Inappropriate dietary restriction is well meant, but misguided advice may exacerbate these potential problems. All will need assessment and support from specialist dietitians with experience in the management of patients with kidney disease (See Chapter 9).

Special considerations

Radiology contrast media (gadolinium/iodinated contrast)

Many patients admitted to hospital need further complex investigations to reach a diagnosis. The use of intravenous contrast-enhanced diagnostic imaging is common practice. Unfortunately intravenous iodinated contrast media have the potential to be nephrotoxic, and this potential is greatest in those with pre-existing kidney injury. Acute-on-chronic kidney injury secondary to contrast media is called contrast nephropathy, and it lengthens hospital stay, increases the need for dialysis and increases mortality. The risk of contrast nephropathy can be reduced by adequate pre-hydration, although it is unclear whether or not isotonic bicarbonate (1.26% sodium bicarbonate) is superior to saline (either 0.45% or 0.9% sodium chloride) (Brar et al. 2008). The addition of oral N-acetylcysteine may reduce the risk further with minimal toxicity (Kelly et al. 2008). Loop diuretics may be harmful and should be avoided (Kelly et al. 2008). Contrast nephropathy is both predictable and potentially avoidable, and therefore all hospitals should have mechanisms in place to identify at-risk individuals prior to administration of intravenous contrast. Once identified, protocol-driven practice should minimise the risk of contrast nephropathy.

Gadolinium is a contrast agent used in magnetic resonance imaging. Reports have linked gadolinium to the development of a rare but devastating condition called nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) in patients with advanced kidney failure (at least stage 4, but predominantly dialysis-treated stage 5 CKD: Nortier & del Marmol 2007). NSF can lead to both severe disability and mortality. Unlike contrast nephropathy, there is no effective strategy to mitigate the risk of developing NSF following gadolinium exposure, leading to a recommendation of avoidance unless the benefits of exposure outweigh the potential risk. More recently, evidence has emerged that the risk of NSF is not equal with all forms of gadolinium, and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority has offered guidance on which forms of gadolinium may be safer if exposure is required (MHRA 2010).

Bleeding (uraemic platelet dysfunction)

Patients with advanced CKD have an acquired disorder of platelet function. This leads to a prolonged bleeding time. This is rarely a clinical issue, but if prolonged bleeding occurs the bleeding time can be corrected by the administration of the synthetic vasopressin analogue desmopressin (DDAVP) at a dose of 0.4 µg/kg over 30 minutes. In our experience, excessive bleeding most commonly occurs due to over-heparinisation, and it always sensible to measure the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT) first and correct these if abnormal. Desmopressin has been most useful in uraemic patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and sphincterotomy, where we encountered significant bleeding prior to the prophylactic use of desmopressin and none since.

Medication management

As with any patient, a careful review of current and planned medication is essential in all patients at risk of AKI or with existing CKD. Specific concerns are:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree