Fig. 44.1

Global prevalence of stunting and underweight in children under 5 years of age [3] CEE Central and Eastern Europe, CIS Commonwealth of Independent States

Deficiencies of essential vitamins and minerals are widespread and have substantial adverse effects on child survival and development. Deficiencies of vitamin A and zinc adversely affect child health and survival, and deficiencies of iodine and iron, together with stunting, contribute to children not reaching their developmental potential. Recent analysis support that all degrees of stunting , wasting, and underweight are associated with higher mortality, while undernutrition can be considered the cause of death in a synergistic association with infectious diseases; all anthropometric measures of under nutrition were associated with increased hazards of death from diarrhea, pneumonia, measles, and other infectious diseases, except for malaria [5]. Besides anthropometric measures, the association between micronutrient deficiencies such as vitamin A deficiency and increased risk of childhood infections and mortality is also well established [7]. Vitamin A deficiency increases the risk of severe diarrhea and thus diarrhea mortality but is not an important risk factor for the incidence of diarrhea or pneumonia, or for pneumonia-related mortality. Other micronutrient deficiencies such as zinc and iron deficiency are also recognized as widespread in developing countries and associated with increased risk of morbidity [8] and mortality [9]. According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, globally about 190 million preschool children and 19.1 million pregnant women are vitamin A deficient (that is, have serum retinol < 0.70 μmol/l) [10]. Globally, 0.9 % or 5·17 million preschool age children are estimated to have night blindness and 33.3 % or 90 million to have subclinical vitamin A deficiency, defined as serum retinol concentration of less than 0·70 μmol/L. Vitamin A deficiency using night blindness prevalence can be defined as a global problem of public health importance [10, 11]. Approximately 100 million women of reproductive age (WRA) have iodine deficiency, and an estimated 82 % of pregnant women worldwide have inadequate zinc intakes to meet the normal needs of pregnancy [6]. Iron deficiency is widespread and globally about 1.62 billion people are anemic [12], and 18.1 % and 1.5 % children are anemic and severely anemic, respectively [4]. Suboptimal vitamin B6 and B12 status have also been observed in many developing countries [13].

Risk Factors

Risk factors for undernutrition range from distal broad national scale determinants to proximal individual specific and factors which effect at various age and periods of life. National socioeconomic and political determinants have a bigger impact and include political stability, economics, food security, poverty, and literacy, among others. Natural disasters including famine, floods, and other emergencies have detrimental effects. Maternal education is associated with improved child-care practices related to health and nutrition, and reduced odds of stunting , and better ability to access and benefit from existing facilities. Worrisome food insecurity is obviously critical, but a factor that is potentially even more important (especially for children with marginal intake) is the inability to absorb what they do take in because of repeated or persistent intestinal infections. Severe infectious diseases in early childhood, such as measles, diarrhea, pneumonia, meningitis, and malaria, can cause acute wasting and have long-term effects on linear growth. But the most important of these infections is diarrhea; hence, the need for understanding the impact and mechanisms of malnutrition and diarrhea, which forms a vicious cycle of enteric infections worsening and being worsened by malnutrition. Several recognized processes by which enteric infections cause malnutrition, range from well-recognized anorexia and increased catabolic or caloric demands to direct protein and nutrient loss or impaired absorptive function [14]. Modifiable risk factors for childhood obesity include maternal gestational diabetes; high levels of television viewing; low levels of physical activity; parents’ inactivity; and high consumption of dietary fat, carbohydrate, and sweetened drinks, yet few interventions have been rigorously tested [15, 16].

Short- and Long-Term Consequences

Malnutrition leads to early physical growth failure, delayed motor, cognitive, and behavioral development, diminished immunity, and increased morbidity and mortality. These nutritional problems particularly flourish during periods in utero and during the first 3 years of life, and especially affect a large proportion of all children in LMICs. The determination of the child nutrition status starts even before birth, as maternal nutrition and health has a significant impact on child health. Neonates with fetal growth restriction are at substantially increased risk of being stunted at 24 months and of development of some types of noncommunicable diseases in adulthood. Those who survive the initial and direct consequences of malnutrition in early childhood grow up as adults but with disadvantages when compared to those who have been nutritionally adequate and enjoyed healthy environment in the initial crucial years of life. Undernutrition is strongly associated, with shorter adult height, less schooling, reduced economic productivity, and for women with lower offspring birth weight. Low birth weight (LBW) and undernutrition in childhood are risk factors for high glucose concentrations, blood pressure, and harmful lipid profiles [17]. The later consequences of childhood malnutrition include diminished intellectual performance, low work capacity, and increased risk of delivery complications [18]. Short-term consequences of intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) involve metabolic, thermal, and hematological disturbances leading to morbidities, while long-term consequences include increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, systolic hypertension, obesity , insulin resistance, and diabetes type II in adulthood [19, 20]. There are no effective therapies to reverse IUGR and antenatal management is aimed at determining the ideal time and mode of delivery. In order to prevent complications associated with IUGR, it is important to first detect the condition and institute appropriate surveillance to assess fetal well-being coupled with suitable intervention in case of fetal distress. A study carried out in Chile shows that undernutrition at an early age may affect brain development, intellectual quotient, and scholastic achievement in school-age children [21]. This pattern is consistent with increased susceptibility to altered brain growth, particularly with the development of altered frontal lobe structures [22]. A recent review found evidence to support a weak association between LBW and later depression or psychological distress; however, the association may vary according to severity of symptoms or other factors [23]. Hence, the prevention of LBW and the promotion of adequate growth and development during early childhood will result in healthier, more productive adults. These undernourished children also show higher susceptibility to the effects of higher fats diets, lower fat oxidation, higher central fat, and higher body fat gain [24]. Without undermining the importance of the early period of life and even before that, evidence also suggests that improvements in child growth after early faltering may have significant benefits on schooling and cognitive achievement. Hence, interventions to improve the nutrition of preprimary and early primary school-age children also merit consideration [25]. Improvements in height may be obtained through adequate nutrient intake after the child’s early years, but the brain is a notable exception because the first 2 years of life represent the period of maximum growth, and 70 % of adult brain weight has been attained by the end of the first year [26, 27].

Global Inclination Toward Undernutrition

There is growing recognition that interventions designed to improve human nutritional status have instrumental value in terms of economic outcomes. In many cases, productivity gains alone provide sufficient economic returns to justify investments using benefit and cost criteria. The often-held belief that nutrition programs are welfare interventions that divert resources which could be better used in other ways to raise national economies is incorrect. Most development agencies have revised their strategies to address undernutrition. The first Lancet nutrition series in 2008 [28] created a much desired stir and drew attention from relevant quarters. One of the main drivers of the new international commitment is the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement [29] and the second Lancet nutrition series [4]. National commitment in LMICs is growing, donor funding is rising, and civil society and the private sector are increasingly engaged. Nearly every major development agency has published a policy document on undernutrition, and donors have increased official development assistance to basic nutrition. Nutrition is now more prominent on the agendas of the UN, the G8 and G20, and supporting civil society. However, this progress has not yet translated into substantially improved outcomes globally. Improvements in nutrition still represent a massive unfinished agenda. The 165 million children with stunted growth have compromised cognitive, development, and physical capabilities, making yet another generation less productive than they would otherwise be [4]. Countries will not be able to break out of poverty and to sustain economic advances without ensuring their populations are adequately nourished. Undernutrition reduces a nation’s economic advancement by at least 8 % because of direct productivity losses, losses via poorer cognition, and losses via reduced schooling [30].

Addressing the Burden of Undernutrition

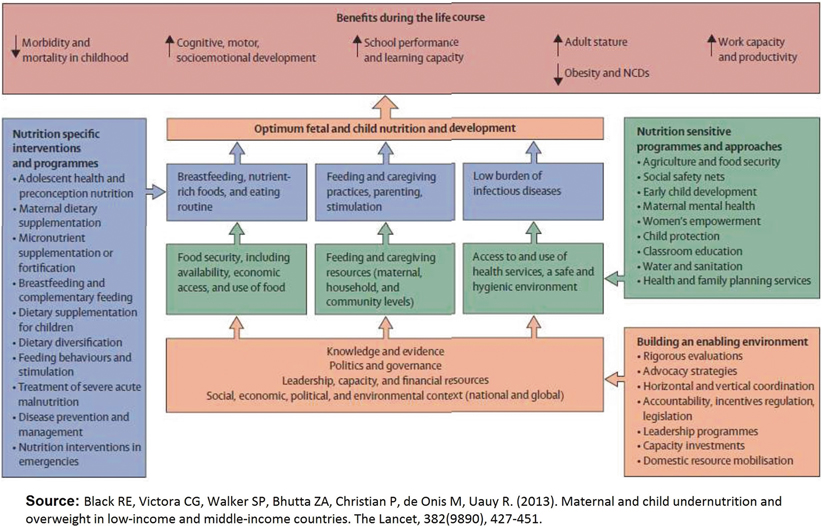

To address this persistent burden of undernutrition in children and to the population at large, various strategies have been employed worldwide (Fig. 44.2). Among these include nutrition education, dietary modification, food provision/supplementation and agricultural interventions including bio-fortification, micronutrient supplementation and fortification. Apart from these direct nutritional interventions, programs to tackle the underlying causes of undernutrition including prevention and management of infections (like diarrhea and malaria) have also been initiated and implemented at various levels of care. Parallel programs have also been pursued to increase coverage and aid uptake of these primary interventions including provision of financial incentives at various levels, home gardening and community-based nutrition education, and mobilization programs. Although all these strategies have shown success and proved to be effective, a coherent, multifaceted, and integrated action which has the global consensus is lacking and several attempts at developing consensus is fraught with controversies and lack of coordination between various academic groups and development agencies.

Fig. 44.2

Conceptual framework for achieving optimal child nutrition. (Reprinted from Ref. [4], with permission from Elsevier) NCDs noncommunicable diseases

There is a need for more emphasis on the crucial period from conception to a child’s second birthday, the 1000 days in which good nutrition and healthy growth can have lasting benefits throughout life. Early years are important to intervene for various reasons as this is the period of maximum growth, immunological systems develop and mature during this time and they are less able to make their needs known and are more vulnerable to the effects of poor parenting. Intervening early in pregnancy and even before conception may be beneficial, as many women do not access nutrition-promoting services until later in pregnancy, so it is important to ensure that women enter pregnancy in a state of optimum nutrition. The emerging platforms for adolescent health and nutrition might offer opportunities for enhanced benefits [31]. There is a growing interest in adolescent health as an entry point to improve the health of women and children, especially as an estimated 10 million girls younger than 18 years are married each year [32].

Broader-Scale Interventions

There is a need for building an enabling environment to support interventions and programs to enhance growth and development. Important determinants of undernutrition to address include poverty, food insecurity, illiteracy, and scarcity of access to adequate care which in turn shape economic and social conditions, national and global contexts, capacity, resources, and governance. These could be addressed through investments in agriculture, social safety nets, early child development, and schooling. Social safety nets provide cash and food transfers to a billion poor people and reduce poverty. They also have an important role in mitigation of the negative effects of global changes, conflicts, and shocks by protecting income, food security, and diet quality [33]. Safety net programs can be more effective, but geographic targeting and other investments to strengthen safety nets are necessary to ensure that fewer people are affected by future crises. Combination of early child development and nutrition interventions makes sense biologically and programmatically, and evidence from mostly small-scale programs suggests additive or synergistic effects on child development and in some cases on nutrition outcomes [33]. Parental schooling is consistently associated with improved nutrition outcomes and schools provide an opportunity, so far largely untapped, to include nutrition in school curricula for prevention and treatment of undernutrition or obesity . School feeding programs is another avenue to improve nutrition at a later life. Recent evidence from in-depth studies argue that while school feeding programs can influence the education of school children and, to a lesser degree, augment nutrition for families of beneficiaries, they are best viewed as transfer programs that can provide a social safety net and help promote human capital investments [34]. Arguably, direct food distribution, including that of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), may be part of the overall strategy. Even if such programs are too expensive for sustainable widespread use in the prevention of malnutrition , scalable food distribution programs may be cost-effective to address the heightened risk of malnutrition following weather-related shocks [35]. Community delivery platforms for nutrition education and promotion, integrated management of childhood illness, school-based delivery platforms, and child health days are other possible channels. Innovative delivery strategies, especially community-based delivery platforms are promising for scaling up coverage of nutrition interventions and have the potential to reach poor and difficult to access populations through communication and outreach strategies.

Targeted agricultural programs have an important role in support of livelihoods, food security, diet quality, and women’s empowerment, and complement global efforts to stimulate agricultural productivity and thus increase producer incomes while protecting consumers from high food prices [33]. Agricultural interventions including home and school gardening have the potential and a review on agricultural interventions to improve nutritional status of children concluded that home gardening interventions had a positive effect on the production of the agricultural goods and consumption of food rich in protein and micronutrients. However, the impacts on iron absorption and anthropometric indices remained inconclusive [36]. Evidence also suggests that targeted agricultural programs are more successful when they incorporate strong behavior change communications strategies and a gender-equity focus.

Food fortification is one of the strategies that has been used safely and effectively to prevent vitamin and mineral deficiencies. A review of multiple micronutrient (MMN) fortification in children showed an increase in hemoglobin levels and 57 % reduced risk of anemia. Fortification is also associated with increased vitamin A serum levels. A review on mass salt fortification with vitamin A and iodine concluded that the fortified and iodized salt can improve the iodine status [37]. Zinc and Vitamin D fortification have also been effective to varying extent [38]. Micronutrient fortified milk and cereal products have also proven as a complementing strategy to improve health problems of children in developing countries [39]. A recent review has identified it as an effective and potential strategy although more rigorous evidence is required especially from LMIC [40]. Bio-fortification is a relatively new strategy to improve iron, zinc, and vitamin A status in low-income populations. It is the use of conventional breeding techniques and biotechnology to improve the micronutrient quality of staple crops. A review on bio-fortification concluded that it has the potential to contribute to increased micronutrient intakes and improve micronutrient status; however, this domain requires further research [41].

Specific Interventions

Many nutrition interventions have been successfully implemented at scale, and the evidence base for effective interventions and delivery strategies has grown (Table 44.1). At the same time, coverage rates for other interventions are either poor or nonexistent.

Table 44.1

Interventions to reduce malnutrition in women and children

Women | Children |

|---|---|

Micronutrient supplementation | |

Iron/iron-folate supplementation | Iron supplementation |

Maternal calcium supplementation | Vitamin A supplementation |

Maternal multiple micronutrient (MMN) supplementation | Zinc supplementation |

MMN supplementation | |

Maternal balanced energy protein supplementation < div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |