MALT Lymphoma (Extra Nodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma)

Among the extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, the stomach is the most commonly involved site in the Western countries, of which MALT-type lymphomas (MALTo-mas or MALT lymphomas) are the most frequent.

1,

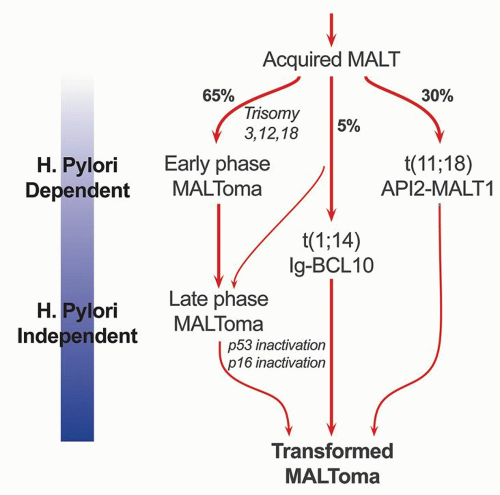

2Pathogenesis. Understanding the pathogenesis of gastric lymphoma has been one of the major triumphs of this past century and continues to lead the way in our understanding of lymphomagenesis (

Fig. 4-14). The association of

H. pylori infection in patients with MALT lymphoma is currently well established.

8,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119 Initial studies showed that

H. pylori is associated with MALT lymphomas in 92% to 97% of the cases—a finding that is similar to gastric carcinoma—80% to 90% of which are also associated with

H. pylori infection.

119,

120 The prevalence of

H. pylori infection in the general population in Western countries is about 30% but is much higher in developing countries where, in contrast to developed countries, children still tend to become infected early in life. Studies of archived gastric biopsies and sequential serological studies have shown that

H. pylori infection precedes the development of gastric MALT lymphomas.

33,

34,

119 With disease progression, the tumor growth tends to become independent of the organisms. At later stages, it is likely that the gastric environment becomes atrophic and no longer conducive to the survival of

H. pylori, and either the organisms disappear or become too sparse to be visualized in biopsies. Thus, it is not surprising that the association of

H. pylori with transformed MALT lymphomas (MALT lymphoma with a large B-cell component) is only 52% to 71%, while with purely DLBCLs (formerly high-grade MALToma) it is only 25% to 38%.

121,

122,

123 Similarly,

H. pylori can be demonstrated in 90% of cases when the tumor is limited to mucosa and submucosa, but in only 76% of the cases with submucosal spread of the tumor, and 48% of the cases when the tumor extends beyond submucosa.

124

The notion that the gastric mucosa (unlike small and large bowels) normally lacks organized lymphoid tissue is belied by experience in which small lymphoid aggregates can be found immediately above the muscularis mucosae even in children who have no indication of ever having had

Helicobacter. However, the lamina propria shows only scattered lymphocytes and plasma cells. It has been hypothesized that

H. pylori induces a lymphoid infiltrate associated with lymphoid follicles that is similar to the MALT of intestines and provides the background for the development of lymphoma.

120 It has been shown in vitro that the tumor cells from a MALT lymphoma proliferate when incubated with heat-killed

H. pylori, but die rapidly in the absence of

H. pylori or when only chemical mitogens are used.

125 This proliferative response also disappears when the T cells are removed from the culture.

126 Addition of supernatant from another culture of unseparated tumor cells fails to restore cell proliferation, suggesting direct contact with T cells rather than secreted cytokines is important.

126 This proliferative response to

H. pylori not only appears to be strain specific for a given tumor, but varies among tumors from different patients. These observations suggest that the tumor is at least in part antigen dependent

and that

H. pylori is the most likely antigen. It is also clear from these experiments that T cells play a vital role in the B-cell proliferation and that the B cells themselves are not

H. pylori specific but make antibodies to a variety of autoantigens, including parietal cells and the proton pump that can result in gradual atrophy of specialized gastric mucosa. While the initial B-cell proliferation is

H. pylori driven and polycloncal, subsequent molecular and genetic alterations lead to clonal expansion and autonomous growth. Whether

H. pylori-specific factors play a role in the development of lymphoma is still somewhat controversial.

127,

128,

129 The

H. pylori strains, which accelerate the tumor growth, include the Cag A strain, a gene found in approximately 60% of

H. pylori organisms, and the vac A (vacuolating cytotoxin) genotype.

129,

130,

131 MALT lymphomas associated with

H. heilmanni infection have also been reported.

132 The cell of origin of MALT lymphomas is a B-cell that is identical to lymphocytes of the marginal zone of lymphoid follicles. These represent postfollicular B cells, and antigen selection occurs in some cases.

133,

134,

135Clinical features. MALT lymphomas occur predominantly in the stomach in middle-aged or older patients although on rare occasions they have been reported in younger patients, as young as 7 years of age.

136,

137 The tumor occurs more commonly in males (M:F = 1.5:1), the mean age being around 60 for males and 65 for females. The majority of the patients present with nonspecific symptoms that include epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, or dyspepsia, similar to peptic ulcer disease. Patients with advanced disease or high-grade lymphomas tend to have signs and symptoms that mimic gastric carcinoma, such as early satiety, weight loss, hemorrhage, and anemia. Some cases may have a frank obstruction accompanied by a palpable mass.

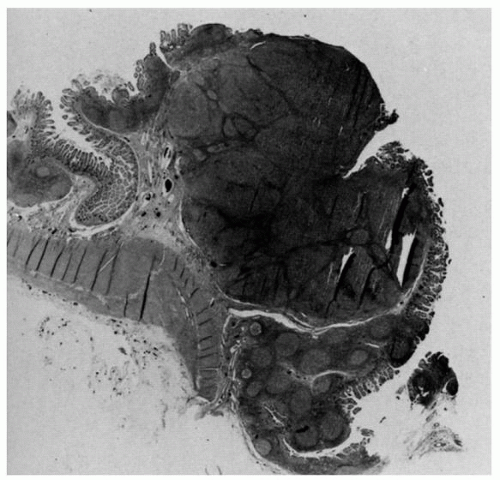

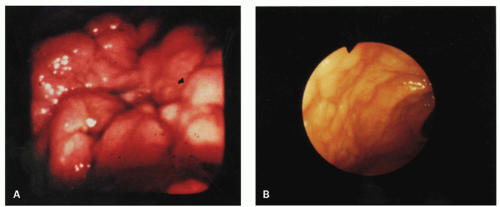

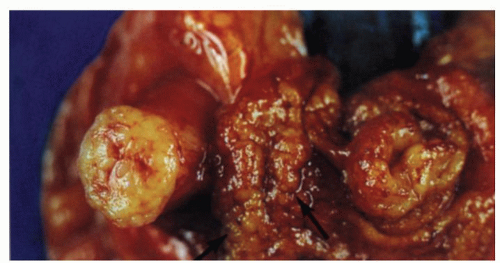

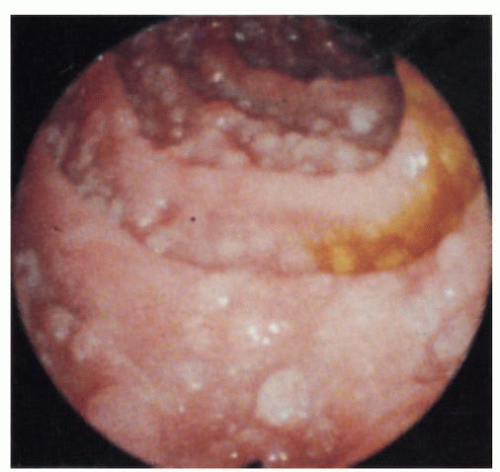

Endoscopically, the tumors often have a varied and nondiagnostic appearance that includes severe thickened folds, superficial erosions, or deep ulcers (

Fig. 4-15). In some instances the mucosa may show only minimal hyperemia or even appear normal. The lesions may be multifocal as shown by the microscopic involvement of apparently normally appearing mucosa in some cases. These findings are also reflected in the imaging studies, either CT scan or ultrasound-based evaluations. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a valuable imaging modality in evaluating the extent of involvement by lymphoma.

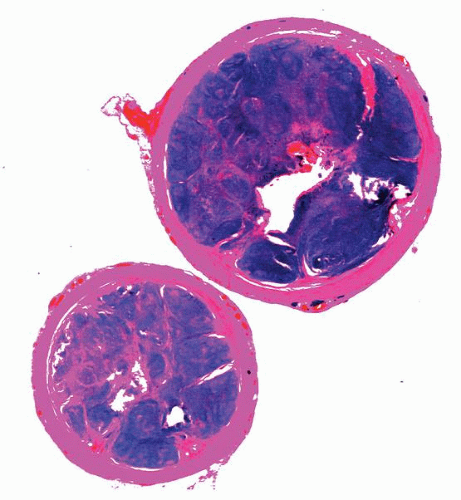

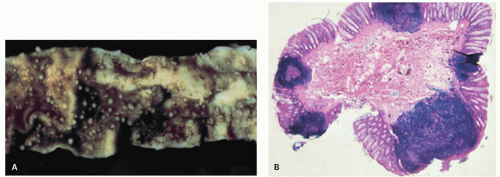

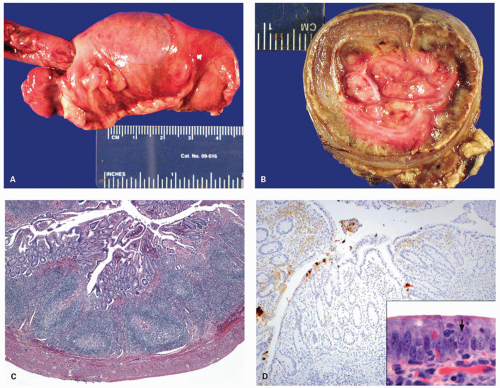

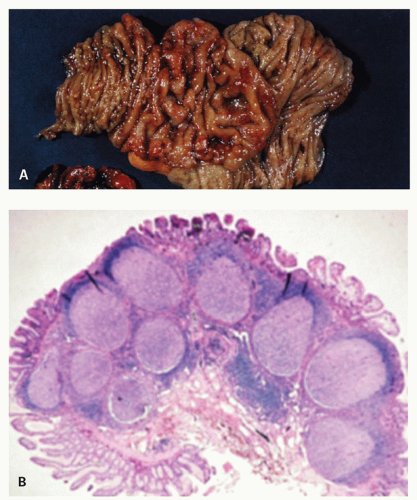

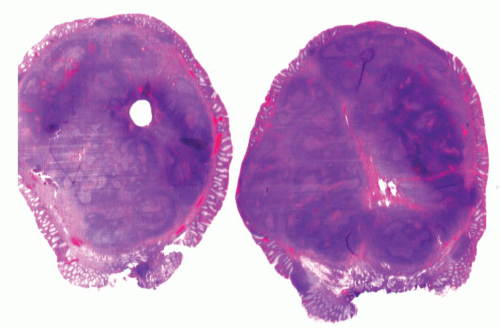

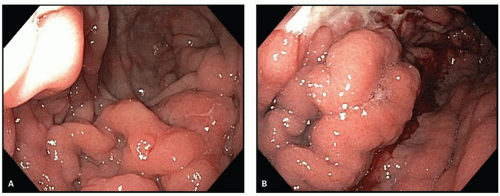

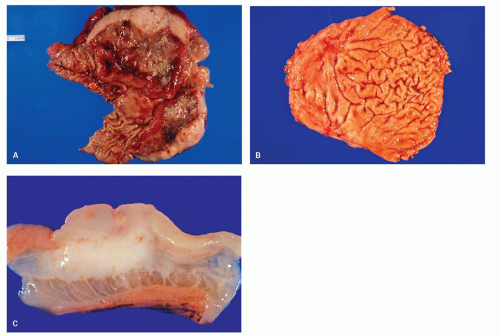

138Pathology. The gross appearance of the tumor is highly varied and includes flat, granular, or nodular mucosa; minimal to mild surface erosions; thickened folds; and ulcers or ill-defined diffusely infiltrative lesions (

Fig. 4-16). However, the most common presentation resembles chronic active gastritis or gastric ulcers. Polypoid masses or ugly ulceroproliferative lesions are most commonly associated with advanced disease or high-grade tumors where the lesions could easily reach 8 cm in diameter. Typically, the lesions are localized to the mucosa and sub-mucosa, and the infiltrative growth results in either uniform or localized thickening of the wall. In some cases tumors are associated with the destruction of the full thickness of the gastric wall without an associated desmoplastic reaction and may lead to perforation. On cut section they have a characteristic white homogeneous fish-flesh appearance. As most of the lymphomas are low grade, detected early, and treated medically, fewer gastric resections with large lesions are encountered in current practice.

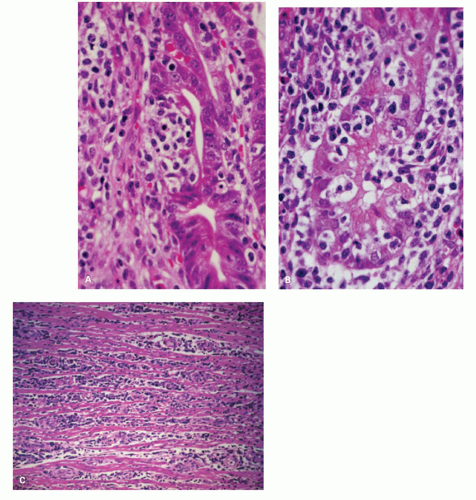

The most common site at presentation is the antrum. However, subsequently the tumor may spread throughout the stomach. Frequently it is multifocal,

although many foci may be microscopic in size. Once the infiltrate extends into the submucosa, it tends to separate the muscle fibers of the muscularis mucosae and either grows in a band-like manner, with a pushing border, or invades with an irregularly infiltrating margin. Eventually, the muscle undergoes atrophy, resulting in the marked weakening of the viscus and a propensity to perforation. The regional lymph node involvement is distinctly uncommon with superficial lesions and is seen once the tumor spreads to the muscularis propria or undergoes transformation to high grade.

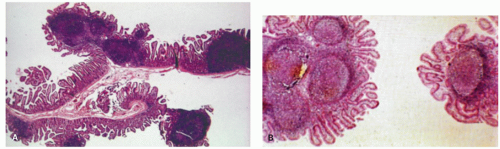

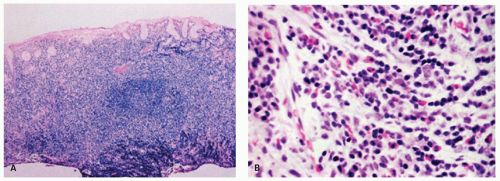

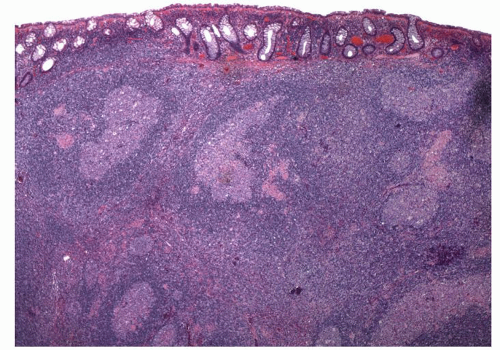

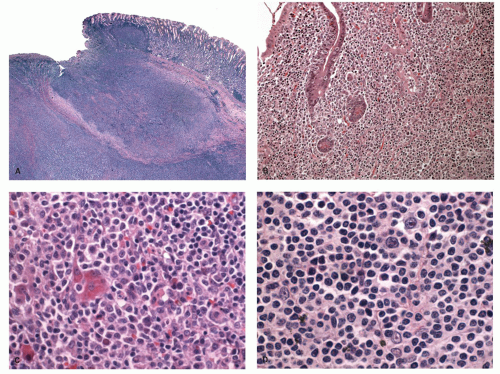

The microscopic findings in MALT lymphomas are also varied and range from chronic active gastritis-like to typical nodal marginal zone lymphomas (

Fig. 4-17). The majority of MALT lymphomas are limited to the mucosa and superficial submucosa, resulting in thickening of the mucosa with separation or gradual replacement of the glandular component. Initially, the crypts or glands are pushed apart from one another and upward from the underlying muscularis mucosae by the lymphoid infiltrate. Morphologically, the MALT lymphomas characteristically have histologic features that mimic normal MALT and are most commonly associated with a background of chronic active gastritis, but in which the monomorphous lymphoma appears to push aside the

Helicobacter gastritis. The tumor cells tend to form monomorphous sheets of lymphocytes and infiltrate into the gastric pits, glands, or surface epithelium. The latter create the lymphoepithelial lesions, which are characterized by clusters of at least three or more atypical B cells infiltrating and destroying the foveolar or glandular epithelium (see

Figs. 4-17 and

4-19). As normal IELs are usually T cells and therefore CD3 immunoreactive, the presence of these cells as B cells also aids with the diagnosis. However, if T-cell stains are carried out, MALT lymphomas appear to be T-cell driven so that the number of T cells is invariably as frequent as B cells to the point that a dearth of T cells should cast doubt on the diagnosis. The damaged epithelial cells often assume an eosinophilic/oncocytic appearance and may not be readily appreciable on H&E sections. In such situations, keratin stains are very useful to highlight the lymphoepithelial lesions. Occasionally, benign-appearing clusters of lymphocytes are found in the surface and crypt epithelium that represent the normal transmigrating lymphocytes. They differ from the lymphoepithelial lesions in that phenotypically they are T cells and they do not destroy the epithelium.

139,

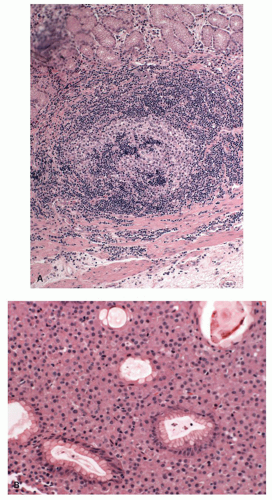

140Lymphoid follicles are almost invariably present in MALT lymphomas and are frequently partially or totally surrounded by a sheath of atypical lymphocytes and plasma cells, which may be reactive or monotypic, occupying the mantle or marginal zones. These cells

tend to spread out from the marginal zone of the follicle to infiltrate the interfollicular zone and destroy the glands. Occasionally, these cells may also infiltrate the center of the follicle (follicular colonization), producing a vague nodular architecture (

Fig. 4-18).

141 This can be easily demonstrated by dendritic cell markers (CD21, CD23, or CD35) that highlight the background of dendritic reticulum cells in the colonized follicle. Another invariable finding in over 90% of these patients is the presence of

H. pylori infection.

Cytologically, the MALT lymphomas frequently consist of an admixture of various lymphocytic cell types, although one cell type may predominate in a given case. The commonly found types of lymphocytes are the following:

1. Small lymphocytes resembling normal mature lymphocytes but differing slightly in that they have somewhat enlarged irregular or wrinkled nuclei with less dense chromatin. MALT lymphomas with predominantly these types of cells may be difficult to distinguish from disseminated nodal small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (SLL/CLL) or occasionally a mantle cell lymphoma.

2. Lymphoplasmacytoid cells often containing intra-cytoplasmic immunoglobulin, commonly of the IgM class, with light chain restriction and Dutcher bodies (intranuclear periodic acid Schiff [PAS] positive inclusions). The presence of lymphoplasmacytoid cells in MALT lymphomas needs to be differentiated from the rare pure “small lymphocytic or plasmacytoid lymphomas” (immunocytomas of the Kiel classification), which are found in lymph nodes, spleen, bone marrow, and less frequently extranodal sites. Some of these cases may be associated with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Some authorities consider this tumor to be distinct from MALT lymphomas.

3. CCLs are lymphocytes intermediate between small lymphocytic and small cleaved cell lymphomas, which have dense nuclei that are irregular in shape but are not as cleaved as the classical cleaved cell lymphoma. Variants of these cells, which have more abundant clear cytoplasm and well-defined cell margins, resembling monocytoid B cells, are frequently found.

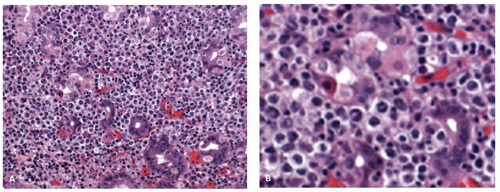

In addition, large noncleaved lymphoblasts or immunoblasts may be scattered in between the small lymphocytes and do not imply high-grade transformation (

Fig. 4-17C). Frequently there are large numbers of interspersed reactive T cells. Mature plasma cells are also frequently present and are most commonly distributed below the surface epithelium. The plasma cell component can be very prominent in some cases and may mimic a primary plasma cell disorder (see

Fig. 4-18B). The cytoplasmic immunoglobulin in the lymphoplasmacytic cells has a perinuclear distribution and may be so abundant that it produces a “signet-ring”-like appearance mimicking a carcinoma.

142 Since the immunoglobulin is preserved in formalin-fixed tissues and is PAS positive, it may cause further confusion with signet-ring cell carcinoma to the unwary, especially in small biopsies. On rare occasions metaplastic goblet cells from the surface or glandular epithelium may become pinched off by the lymphoid infiltrate and appear to lie isolated in the stroma, simulating signet-ring cell carcinoma.

Immunophenotype and molecular genetics. Immunohistochemically, the lymphomatous cells express surface and to a lesser extent cytoplasmic immunoglobulin, primarily IgM, which shows light chain restriction and rarely IgG or IgA. In addition, they are characteristically CD5, CD10, BCL1, and CD23 negative, but positive for the other B-cell markers (CD20, CD21, CD22, CD35, BCL2, CD79a, and CD23) and often CD43.

8 In small biopsies, it may not be possible to perform all the markers, and one has to wisely choose a small panel that helps to differentiate MALT lymphoma from its mimics in a given case (see

Table 4-5).

Many genetic and epigenetic abnormalities have been described in MALT lymphomas. However, most MALT lymphomas (about 70%-85%) do not have a specific translocation, yet there are four translocations that are specifically associated with MALT lymphomas and at the molecular level share a physiological role for BCL10 and MALT1 in antigen receptor-mediated NFkB activation.

143 These include chromosomal translocations: t(11;18)(q21;q21), important because it predicts lack of response to

Helicobacter eradication therapy, and t(1;14)(p22;q32) and t(14;18)(q32;q21) that seem to be specific for MALT lymphomas and have diagnostic and prognostic importance.

144,

145,

146 Another more recently recognized translocation with MALT lymphomas is t(3:14)(p14.1q32) and suggests a role of FOXP-1. The proposed molecular mechanisms and pathogenesis of

H. pylori-associated MALT lymphomas are shown in

Figure 4-14. Other abnormalities include trisomies 3,12,18;

p53 mutation/LOH;

p15 and

p16 promoter methylation; and

fas mutation.

147,

148,

149,

150,

151,

152,

153,

154Translocation t(11;18)(q21;q21) In most of the translocation positive cases, t(11;18)(q21;q21) is the sole chromosomal abnormality.

144,

145 This translocation causes reciprocal fusion of the API2 and MALT1

genes.

155,

156,

157 The API2 is an apoptosis inhibitor, whereas MALT1 is involved in antigen receptor-mediated NFkB activation. The fusion transcript is consistently expressed in these cases and is believed to be oncogenic. Unlike wild-type API2 and MALT1, API2-MALT1 fusion product is a potent activator of NFkB. NFkB activation in turn leads to activation of other cytokine and growth factor genes that are important for cellular activation, proliferation, and survival, thus contributing to tumor development.

158,

159,

160 This translocation is seen in about 15% to 30% of gastric MALT lymphomas.

161 The same translocation has also been described in MALT lymphomas of other sites including skin and lungs. However, it is absent in nodal and splenic marginal zone lymphomas.

162,

163,

164,

165 Cases of

H. pylori gastritis also do not show this translocation. MALT lymphomas with this translocation do

not respond to

H. pylori eradication and more often spread to distant sites including regional lymph nodes.

166 An initial report suggested that despite the association of t(11;18)(q21;q21) with adverse clinical features, the translocation is uncommonly found in cases with DLBCLs or so-called transformed MALT lymphomas, that is, low-grade MALT lymphomas with a large-cell component.

167,

168 A subsequent study however shows that this translocation is seen with almost equal frequency in transformed MALT lymphomas or DLBCLs of the stomach.

169 Even if found,

H. pylori eradication treatment is undertaken together with other lymphoma therapy.

Translocation t(1;14)(p22;q32) The second common MALT lymphoma associated translocation is t(1;14) (p22;q32). Cases positive for this translocation are often

associated with trisomies 3, 12, and 18, unlike t(11;18) (q21;q21).

146 The translocation brings the entire BCL10 gene under the regulatory control of the Ig gene and deregulates its expression.

143,

170 Earlier studies showed that although BCL10 activates NFkB, it is weakly proapoptotic.

171,

172 However, subsequent studies have shown that BCL10 does not have proapoptotic activity in vivo.

173,

174 It is essential for the development of B- and T-cell functions and specifically links the antigen receptor signaling to NFkB pathway.

175,

176,

177 In response to the surface antigen receptor stimulation, BCL10 oligomerizes and binds to MALT1, leading to MALT1 oligomerizartion that in turn activates NFkB. In line with the physiological role of BCL10 in normal B cells, the protein is expressed predominantly in the cytoplasm of germinal center B cells.

178 BCL10 is strongly expressed in the nuclei of MALT lymphomas with t(1;14)(p22;q32) or its variants.

178 However, moderate nuclear BCL10 expression is also seen in about 50% of cases negative for this translocation and in almost all t(11;18)(q21;q21)-positive cases.

161,

165,

179 Studies using BCL10 immunostains and interphase FISH analysis show that t(1;14)(p22;q32) is specifically associated with MALT lymphomas and not with other lymphoma subtypes.

165 This translocation occurs in about 5% of gastric MALT lymphomas and has also been associated with MALT lymphomas of lungs.

165 Gastric MALT lymphomas with this translocation are typically at advanced stages and unlikely to respond to

H. pylori eradication.

Translocation t(14;18)(p32;q21) The third MALT lymphoma associated translocation t(14;18)(p32;q21) is different from the similar translocation seen in follicular lymphomas. In follicular lymphomas this translocation brings BCL2 at 18q21 in proximity to Ig heavy chain (IgH) locus. The same breakpoint in MALT lymphomas involves MALT1 instead of BCL2.

180 It is proposed that IgH-MALT1 fusion results in activation of MALT1 that somehow stabilizes BCL10 in the cytoplasm. BCL10 in turn then leads to aberrant activation of NFkB pathway. This translocation has so far been shown to be associated with MALT lymphomas of the lungs and ocular adenxae, but not stomach.

164,

180,

181

Translocation t(3;14)(p14;1q32) This is the more recently recognized MALT lymphoma-associated translocation that brings FOXP1 gene in proximity to Ig heavy chain gene and results in its deregulation.

182 FOXP1 belongs to the Forkhead box family of winged-helix transcription factors that have diverse function in different cell types and plays an important role in B-cell development. This translocation was detected in a single case (1.7%,

n = 59) of MALT lymphoma studied and seems to correlate with poor outcome and transformation to DLBCL.

182,

183 This translocation has also been reported in isolated cases of gastric DLBCL.

Treatment and prognosis. These are typically slow-growing lesions that remain localized to the stomach for long periods (stage 1E), often more than 7 to 10 years.

138,

184,

185 The majority of gastric MALT lymphomas at the time of presentation are confined to the mucosa and submucosa. There is a low incidence of mesenteric node involvement and extraintestinal dissemination, although in one study bone marrow involvement was found in 10% of the patients.

5 Recurrence of these low-grade tumors occurs primarily in patients with an increased number of transformed lymphocytes (5%-10%) and involves the original site or other parts of the GI tract, mesenteric lymph nodes, or Waldeyer ring, rather than widespread extraintestinal dissemination.

The overall prognosis of these patients is excellent. As has been discussed earlier, remission of the majority of MALT lymphomas (67%-90%) occurs following the treatment of

H. pylori.

186,

187,

188 This is largely applicable to tumors that do not have a high-grade component and are localized to mucosa or superficial submucosa. Advanced tumors or those with a high-grade component have also been reported to respond to

H. pylori eradication, but infrequently. In several large studies, 90% of patients survived for 5 years and 65% to 75% of patients for 10 years. Whether the patients are truly cured still remains to be determined. Relapses have been shown to occur in about 10% of patients.

189 In some patients, the relapses have been associated with reinfection with

H. pylori and successful remission following eradication of the infection again.

It is increasingly becoming clear that molecular genetics has an important role in predicting the behavior of gastric MALT lymphomas. Tumors with t(11;18) (q21;q21) translocation generally do not respond to

H. pylori eradication, even though they are rarely associated with large-cell transformation. Chemotherapy (sometimes with radiation) and occasionally surgery are the options for cases that do not respond to

H. pylori eradication. Surgical resection on its own has been associated with prolonged survival in some studies.

190 Involvement of the resection margin and advanced stage are poor prognostic factors, but not when adjuvant chemotherapy is also used.

191 These tumors invariably express CD20, and resistant cases or those with large-cell component have been successfully treated with rituximab; however, long-term outcome of such cases is still unknown.

192 Irrespective of the treatment modality, the only independent prognostic variables are stage and tumor grade.

191,

193,

194,

195,

196Reporting MALT lymphomas. There is considerable variation in how pathologists report gastric MALT

lymphomas in biopsies. When the biopsies are adequate and the morphology and immunohistochemistry are typical, many are comfortable making the diagnosis, while some always hedge by stating “consistent with”. One of the problems with MALT lymphomas is the lack of a distinct immunohistochemical profile, and stains are largely used to exclude other lymphoma types (mantle, follicular, CLL etc). Presence of one of the MALT associated translocation should certainly help one in making a definitive diagnosis however, these are present only in a small proportion of cases and are still not readily available in all labs. Nevertheless, pathologists should still be comfortable making this diagnosis in the presence of appropriate histology with the knowledge that the first line of therapy is

Helicobacter eradication followed by re-endoscopy and biopsy a few months later. If the morphology and immunohistochemistry are all correct, but

Helicobacter cannot be demonstrated or the biopsies are too small, reporting them as “atypical lymphoid infiltrate” and suggest follow-up biopsies for a full lymphoma work-up with flow-cytometry, molecular assays and serology for

Helicobacter.

Follow-up of patients with treated MALT lymphoma. Follow-up of these patients after therapy involves periodic endoscopic and EUS examinations and biopsies.

197 It should be remembered that where there has been an endoscopically visible lesion associated with

Helicobacter, following its eradication the primary purpose of the endoscopy is to ensure that the lymphoma is regressing or at least not increasing in size. The latter would suggest incomplete eradication of

Helicobacter, a translocation associated with lack of response to

Helicobacter therapy or a large-cell component. Biopsies would therefore be

expected to contain residual MALT lymphoma, and the demonstration that this is the case is unnecessary.

Role of the pathologist. The role of the pathologist is therefore not to just confirm the presence of residual lymphoma, which is a given as these cells are long-lived and may persist for long periods of time following the withdrawal of the antigenic stimulus, but to also

1. Identify the presence of a large-cell component when present.

2. Identify Helicobacter if present (coccoid forms are not acceptable and are much more likely to be oral or enteric in origin). It should also be recalled that patients on long-term PPIs may allow oral organisms to grow in their stomachs. These are usually polymorphous and can include fungi. Helicobacter therefore have to be photographable (stand up in court) but are important to identify as the lymphoma will not regress until eradication is complete.

3. A useful stain is Mib-1 to evaluate the proportion of cells in non-G0 phase of cell cycle, especially if this can be compared with a pretreatment biopsy, as the proliferation usually falls off markedly once the antigenic stimulus is withdrawn. In the absence of a large-cell component, a persistently high Mib-1 rate suggests persistent Helicobacter, but if these are really absent, one needs to carry out translocation studies. Although monoclonal antibodies to one of the translocation products and also BCL10, which has been suggested as a surrogate marker, are helpful, at the time of writing these are not reliable enough to be part of routine practice. However, in some centers it is thought that there is an economic advantage in looking for the translocations, especially the t(11;14), as it can be predicted that these will not respond to Helicobacter eradication, so the patients will need chemotherapy (which does not preclude Helicobacter eradication).

The long-term follow-up biopsies from patients continuing to respond to

Helicobacter eradication therapy ultimately show that the number of biopsies with MALT tend to diminish and disappear over time. At this stage biopsies often show an empty-looking lamina propria with rare B cells or plasma cells.

198 Sometimes small aggregates of normal-appearing small lymphocytic B cells and scattered T cells are also evident and do not imply residual/recurrent lymphoma. Studies using PCR and Ig gene rearrangement have shown that residual clones can be identified in many cases without any histologic evidence of residual disease.

197,

199 It has been shown that histologic remission may take many months or years (median 33, range 0-65 months), while molecular remission takes longer.

198,

200,

201,

202 At present, the significance of the persistent molecular abnormality in the setting of clinical and histologic remission remains unclear. However, current data also do not justify further treatment of persistent monoclonality by molecular assays in the absence of histologic or clinical disease.

Lastly, it should be noted that the patients with MALT lymphomas also seem to have an increased incidence of gastric adenocarcinoma.

203 This often arises in the distal stomach and appears to occur irrespective of the type of therapy for the lymphoma.

Differential diagnosis and practical approach to the difficult diagnosis. Whenever there is dense lymphocytic infiltrate in the gastric mucosal biopsies, the differential diagnosis includes a lymphoma. The problems often one faces in this situation are as follows:

1. When the infiltrate is polymorphous, the issue is to differentiate between H. pylori-associated chronic active gastritis and MALT lymphoma.

2. When only a small focus of B lymphocytes invading a crypt forming an isolated lymphoepithelial lesion is identified (mini-MALT lymphoma).

3. When the lymphocytic infiltrate is clearly neoplastic, the issue is the correct subclassification of the lymphoma.

Chronic Gastritis versus Malt Lymphoma This situation is frequently encountered in routine practice. The lymphocytic infiltrate in lymphoma tends to be more destructive and expansible, with extensive permeation between the glands. The presence of significant numbers of small cleaved cells (CLC or monocytoid B cells) also supports the diagnosis; however, in some cases these features are not readily evident. The presence of convincing lymphoepithelial lesions strongly favors the diagnosis of MALT lymphoma, although one needs to be careful as they can also be seen in florid H. pylori gastritis (usually single, consist of <3 cells and rarely destructive) as well as other types of lymphomas. The presence of Dutcher bodies or intranuclear inclusions in more than a few plasma cells is also suggestive of lymphoma; however, similar to other sites mere presence of these inclusions by itself is not diagnostic. In reactive lymphoid infiltrate the B cells are typically organized in nodules even though the lymphoid follicles may not be easily evident, and the T cells reside in the interfollicular zones. This pattern can be easily appreciated with CD20 and CD3 immunostains. If CD20 stain shows a diffuse densely packed infiltrate of B cells with limited number of interspersed T cells, this pattern supports a diagnosis of lymphoma. Light chain restriction using immunostains for κ and λ light chains may be helpful in demonstrating a monotypic Ig supporting the diagnosis of lymphoma. However, interpretation of these immunostains performed on paraffin sections is not always straightforward unless overtly plasmacytic. In addition, a polyclonal infiltrate of chronic gastritis often coexists in the background, and one needs to carefully interpret the stain in the atypical cells. Coexpression of CD43 by CD20-positive B cells also supports the diagnosis of lymphoma, although a normal immunophenotype does not exclude this possibility. Detection of a clonally rearranged Ig gene by PCR in the presence of atypical infiltrate is diagnostic of lymphoma. However, a diagnosis of lymphoma should never be based solely based on this finding. Demonstration of any of the MALT lymphoma-associated translocations as discussed above using RT-PCR or FISH is also diagnostic of lymphoma. This not only provides an evidence of a clonal B-cell expansion but represents a MALT-specific abnormality that also has a prognostic significance. If the studies are inconclusive or equivocal, and the biopsy shows an evidence of H. pylori gastritis, repeat biopsies can be suggested following the treatment for H. pylori. In such a setting, it would be appropriate to use the designation “atypical lymphocytic infiltrate of uncertain nature or significance.” If in a similar setting H. pylori is negative, repeat biopsy with more sampling should be suggested sooner than later. If biopsies are performed for confirming a diagnosis of lymphoma, it is advantageous to have additional samples for flow cytometry and molecular studies obtained at the outset.

Mini-MALT Lymphomas In Helicobacter-positive patients, one sometimes comes across a focus of monotonous lymphoid cells surrounding one or two pits that contrasts with the plasma cell rich polymorphous infiltrate of the background gastritis. Further, there may be a focus of IELs mimicking a lymphoepithelial lesion, although these are rarely destructive. In our experience, some of them even show B-cell clonality based on immunoglobulin gene rearrangement studies. These likely represent the earliest stages of MALT lymphoma and likely disappear following H. pylori eradication. Since prospective studies looking at the natural history of such lesions are lacking, a cautious approach is warranted. We do not report these as MALT lymphomas but do not ignore them completely either, stating that a lymphoepithelial-like lesion is present associated with the Helicobacter gastritis and that this will likely disappear following Helicobacter eradication therapy. While calling such lesions as outright MALT lymphoma in the absence of any supportive molecular evidence may be an overkill, a suggestion in the report that Helicobacter eradication therapy should be considered to ensure these lesions do not progress is justified. Given the frequency of these lesions if carefully looked for and the rarity of MALT lymphomas, it is likely that progression of these lesions to overt MALT lymphoma is extremely rare.

Subtyping of a Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma In some cases, the lymphomatous nature of the infiltrate is obvious on histology due to the monotonous appearance of the infiltrate, its destructive nature, or cellular anaplasia. However, not all lymphomas of the stomach are MALT lymphomas, and proper subtyping of the lymphoma is essential as the clinical outcome of similar-appearing lesions is vastly different. The difficulties often arise due to small sample size or crush artifacts that obscure the histologic details and pattern. The entities that often come into the differential diagnosis include SLL/CLL, follicular lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma. The presence of lymphoepithelial lesions, though helpful, is not diagnostic in this situation as they have been described with a variety of other primary or secondary lymphomas of the stomach. Immunophenotyping and demonstration of specific translocations are

extremely valuable in this setting. However, if the sample is small and the findings are inconclusive, additional biopsies for diagnostic workup should be requested. CLL/SLLs have often involvement of peripheral blood, and knowledge of the peripheral blood findings could be helpful.

One of the most difficult and controversial issues is the recognition of DLBCL or, as formerly called, “large-cell/high-grade transformation” of MALT lymphomas (also see later). As defined in the WHO classification, the presence of sheets of large B cells is required to make this diagnosis; however, what constitutes a “sheet” is unclear.

29 Scattered centroblasts and immunoblasts intermingled with the infiltrate are not uncommon in MALT lymphomas, and it has been suggested that more than 10% of large cells should prompt a diagnosis of DLBCL. More than 30% staining with Ki67 has also been suggested to support the diagnosis of DLBCL.