Obstructive symptoms

Overactive symptoms

Incontinence symptoms

Hesitancy

Frequency

Urinary incontinence

Decreased force of stream

Nocturia

Stress incontinence

Intermittency

Urgency

Urgency incontinence

Straining

Urgency incontinence

Mixed incontinence

Position-dependent micturition

Increased sensation

Postural incontinence

Incomplete emptying

Dysuria

Nocturnal enuresis

Double voiding

Bladder pain

Continuous incontinence

Post void dribbling

Insensible incontinence

Urinary retention

Coital incontinence

LUTS Suggestive of Obstruction

LUTS suggestive of obstruction occur during the voiding/emptying phase of micturition or immediately following. Patients may experience one or a multitude of urinary symptoms of varying severities. Patients tend to seek care when symptoms become bothersome, interrupt sleep, or lead to embarrassment.

Symptoms suggestive of obstruction are described below [6].

Urinary hesitancy is the complaint of a delay in initiating the urinary stream.

Decreased force of urinary stream or poor flow is the complaint of a slower stream than previously appreciated or a slower stream than their peers.

Intermittency is the complaint of urinary flow that stops and starts one or more times during the voiding phase.

Straining to void is the complaint of needing to exert effort by Valsalva, suprapubic pressure, or other means of increasing abdominal pressure in order to initiate or maintain the urinary stream.

Position-dependent micturition is the complaint of having to contort one’s body into a specific position in order to improve the force of urinary stream or bladder emptying.

Incomplete bladder emptying is the complaint that the bladder is not empty immediately after voiding.

Double voiding or the need to immediately re-void is the complaint that further micturition is needed soon after voiding.

Post void dribbling is the complaint of involuntary urinary leakage immediately after voiding.

Urinary retention is the complaint of the persistent inability to pass urine.

Etiology of Obstructive Symptoms

The etiology of obstructive symptoms may be anatomic, secondary to an enlarged prostate gland in men, bladder neck obstruction, urethral stricture, urethral compression/fibrosis in women, or pelvic organ prolapse in women. The etiology of symptoms may also be functional, secondary to detrusor striated or smooth sphincter dyssynergia, a fixed bladder outlet, Fowler’s syndrome in women, or poor bladder function (impaired bladder contractility). On occasion, LUTS suggestive of obstruction may exist in the absence of any anatomic or functional cause.

Increased outlet resistance is a much more common phenomenon in men than in women, with BPE being the leading cause. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) refers to typical histopathologic findings of glandular and stromal proliferation that occurs in nearly all men if they live long enough. The location of this growth within the prostate gland, surrounding and adjacent to the prostatic urethra (in the transitional and central zones), is what leads to voiding symptoms (Fig. 10.1). In many men however, the presence of BPH is confirmed pathologically in the absence of voiding symptoms. BPE refers to the increased size of the prostate but implies that a benign pathology has been confirmed. Benign prostatic obstruction (BPO) is a form of bladder outlet obstruction and this term is used when the cause of anatomic obstruction is known to be due to BPH. When histologic confirmation has not been made, preferred terminology is “LUTS suggestive of BPO” [7].

Fig. 10.1

Prostatic zonal anatomy (a) schematic, (b) sagittal cross-section, (c) transverse cross-section (adapted from Hanno et al. [5])

The prevalence of BPH on autopsy increases with age with 25% of men 40–50 years, 50% of men 50–60 years, 65% of men 60–70 years, 80% of men 70–80 years, and 90% of men 80–90 years showing histopathologic change [8]. Similarly, the prevalence of bothersome LUTS as measured by validated questionnaire, the American Urologic Association Symptom Score (AUASS), increases with advancing age [9]. However, clinical BPH varies widely with only a small percentage of those with histologic findings presenting for treatment of bothersome LUTS. Importantly, the size of the prostate gland is not linearly correlated to urodynamic evidence of obstruction or to severity of symptoms and therefore cannot be used as an indicator for treatment [10]. Similarly, small changes in prostatic size and tone can greatly improve LUTS thus explaining the large beneficial effects seen from medical management.

A basic evaluation of men presenting with LUTS should include a thorough medical history including the nature and duration of LUTS. Additional history should include any genital or sexual symptoms, prior urinary tract manipulation or surgery, and medication assessment. Physical exam should include a digital rectal exam to assess prostate size, consistency, presence of nodules, and anal sphincter tone. Palpation of the bladder to rule out distension should be performed and a basic neurologic assessment of motor and sensory function in the perineum and lower extremities is warranted. Urinalysis in the form of a dipstick should be carried out, with further evaluation if abnormalities are seen. In the evaluation of patients with LUTS suspected to be due to BPH there is no consensus on routine prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing. Despite a lack of correlation between prostate symptoms, histology, size and even flow rate, an important relationship with PSA does exist. PSA, in men with BPH and no evidence of cancer, correlates with total prostate volume and is a predictor of the risk of acute urinary retention and ultimate need for surgery. Furthermore, it can be useful as a parameter for prognostic value for BPH progression and response to treatment [11–14]. Essentially, men with larger prostate glands and higher PSA values are at greater risk of experiencing further prostatic growth, worsening LUTS, progression to acute urinary retention and surgical intervention for their condition. Inevitably however, the routine use of PSA in this population will lead to several unnecessary prostate needle biopsies with their resultant complications, and diagnosis of clinically relevant and clinically irrelevant prostate cancer. The risks and benefits of PSA testing should be discussed with the patient.

A quantitative assessment of LUTS and degree of bother is recommended at the time of initial evaluation. The AUASS is a noninvasive, valid, reliable, and responsive index that correlates to the magnitude of urinary problems attributed to BPH (Table 10.2). A score of 7 points or less is considered mild LUTS, 8–19 points moderate LUTS, and 20–35 points severe LUTS. An addition quality of life measure allows for assessment of bother on a scale of 0–6 (delighted to terrible). This tool allows monitoring of symptoms over time, either in response to treatment or in the absence of treatment. The AUASS cannot be used as a diagnostic test or screening tool for BPH as it is nonspecific for BPH, in fact, women with OAB often attain very high scores. Neither PSA nor AUASS can replace a thorough history and physical exam in the evaluation of LUTS felt to be secondary to BPH.

Table 10.2

American Urologic Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia (range from 0 to 35 points)

Not at all | Less than 1 time in 5 | Less than half the time | About half the time | More than half the time | Almost always | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1. Over the last month how often have you had a sensation of not emptying your bladder completely after you finished urinating? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

2. Over the last month how often have you had to urinate again less than 2 h after you finished urinating? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

3. Over the last month how often have you found you stopped and started again several times while urinating? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

4. Over the last month how often have you found it difficult to postpone urinating? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

5. Over the last month how often have you had a weak stream while urinating? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

6. Over the last month how often have you had to push or strain to begin urinating? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

7. Over the last month how many times did you most typically get up to urinate from the time you went to bed until the time you got up in the morning? | 0, none | 1 time | 2 times | 3 times | 4 times | 5 or more times | |

AUA symptom index score: 0–7 mild, 8–18 moderate, 19–35 severe symptoms | Total | ||||||

Quality of life due to urinary symptoms | |||||||

Delighted | Pleased | Mostly satisfied | Mixed about equally satisfied and dissatisfied | Mostly dissatisfied | Unhappy | Terrible | |

1. If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary condition just the way it is now, how would you feel about that? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Quality of life assessment index (QOL) = | |||||||

Quality of life assessment recommended by the World Health Organization | |||||||

A voiding diary should be completed by the patient to document the number of daily voids, the distribution of voids during the day and night, the volume voided, and fluid intake. Other parameters when present such as urgency and leakage of urine should also be documented.

The natural history of BPH is such that slow progression of symptoms over time is expected. Approximately 50% of the time patients with significant outlet obstruction develop overactive symptoms producing a combination of symptoms that exist during bladder filling and emptying. There has been a recent interest in initiating treatment to stabilize symptoms, reverse the natural progression of BPH, and avoid undesirable effects. Most men who seek treatment ultimately do so because of the bothersome nature of their symptoms which affects their quality of life. Treatment involves relief of the obstruction either by anatomic removal of the prostatic bulk or pharmacologic reduction in prostatic tone (alpha blockers) or size (5-alpha reductase inhibitors). Generally relief of obstruction results in diminution of OAB symptoms; although, these symptoms may return as the patient ages.

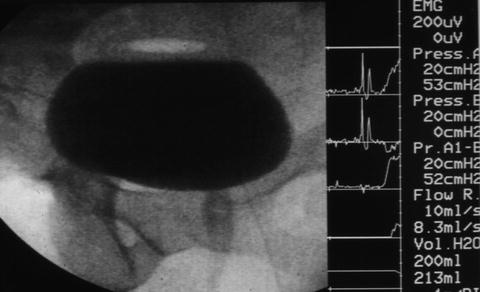

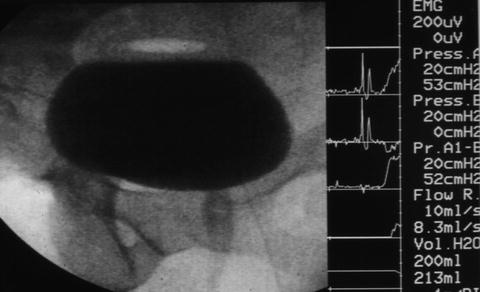

Primary bladder neck obstruction (PBNO) is a condition where the bladder neck fails to open adequately during voiding resulting in poor urinary flow [15, 16]. It is found most commonly in young to middle aged men, but may be seen in women and children as well [17, 18]. Symptoms are similar to those seen from prostatic obstruction, but on examination an enlarged prostate is not appreciated. In many situations patients go undiagnosed for many years and undergo multiple empiric treatments with various medications including antibiotics. The diagnosis is made urodynamically with confirmation of high pressure low flow voiding and fluoroscopic imaging confirming a failure of the bladder neck to relax with voiding (Fig. 10.2). Initial treatment includes a trial of alpha blockers; however, often definitive relief with transurethral incision of bladder neck (TUIBIN) is needed.

Fig. 10.2

Primary bladder neck obstruction documented fluoroscopically with failure of the bladder neck to funnel during voiding. A high pressure (52 cm H2O) low flow (8.3 mL/s) pattern was seen on the urodynamic tracing

Bladder neck contracture (BNC) is generally iatrogenic, occurring after radical prostatectomy, outlet reduction for BPO, transurethral resection of the prostate, or various other alternative strategies for treating BPO. The contracture is composed of scar tissue, preventing appropriate funneling of the bladder neck during voiding. The scar tissue may progress to complete luminal obliteration preventing any flow or urine or passage of instruments through the urethra. BNC rarely responds to medication therapy and commonly requires dilation or more definitive transurethral incision or resection of the bladder neck. Urethral stents have been used with mixed outcomes in attempts to avoid anastamotic urethroplasty, a technically challenging operation. The major risk of these interventions is urinary incontinence often requiring subsequent artificial urinary sphincter placement. This however should be delayed until confirmation of sustained opening of the contracture is confirmed. Recalcitrant contractures require major reconstructive surgery such as appendicovesicostomy, augmentation cystoplasty, and continent catheterizable stomas [19]. Chronic suprapubic tube drainage has been used as a less invasive means of management.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree