Lower urinary tract syndrome is common in children. Incontinence, urinary tract infection, vesicoureteral reflux, and constipation are commonly associated with this syndrome. Examining the clinical history of the afflicted patient plays a major role in the accurate diagnosis and treatment of lower urinary tract disorder. Along with pharmacologic treatment, pelvic floor muscle retraining, biofeedback therapy, and adaptation of a healthy lifestyle are advocated for rapid recovery of patients.

Identification and treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD) of childhood is a common problem facing pediatric urologists. Children with LUTD may present with incontinence, urinary tract infection (UTI), vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), and constipation alone or in combination. About 20% to 30% of children are estimated to experience symptoms related to dysfunctional voiding (DV). Epidemiologic studies have found that the rates of incontinence and enuresis is as high as 20% in school-aged children. These problems alone may account for 30% to 40% of visits to the pediatric urologist.

Proper management of LUTD has evolved with the understanding of the pathophysiological mechanism of DV and the overactive bladder of childhood. Focus has moved from primarily pharmacologic treatment, consisting mainly of anticholinergic and antibiotic prophylaxes, to programs of education, hydration, treatment of constipation, and computer-assisted pelvic floor muscle retraining (PFMR). Current recommendations emphasize conservative management and a less invasive approach. This article discusses the proper evaluation, diagnosis, and management of the neurologically normal child presenting with symptoms of incontinence, based on the current understanding of this common yet under-recognized pediatric problem.

Definitions

The International Continence in Children Society (ICCS) recently updated the standard definitions of commonly used terms to describe abnormalities of lower urinary tract function. “Frequency” can be either increased or decreased. Increased frequency refers to 8 or more voids daily whereas decreased frequency refers to 3 or fewer voids daily in a child older than 5 years. “Incontinence” is uncontrolled leakage of urine and may be categorized as “continuous” or “intermittent”. Continuous refers to constant urine leakage that is seen nearly exclusively in congenital abnormalities whereas intermittent refers to discrete urine leakage in children older than 5 years. “Enuresis” describes intermittent incontinence at night and refers to any discrete leakage of urine at night. The term “Diurnal enuresis” is no longer used and instead “diurnal incontinence” or “daytime incontinence” is used to describe incontinence during wakeful hours. “Nocturia” refers to waking to void separate from waking secondary to enuresis. “Urgency” refers to sudden and unexpected experience of an immediate need to void. “Voiding dysfunction” has been used as a broad term to describe LUTD and is no longer an acceptable term. “Dysfunctional voiding” describes habitual contraction of the urethral sphincter and has been used if a uroflow pattern of staccato voiding is seen or confirmed with urodynamics. Recently, the ICCS published terms describing DV that broaden the definition to include cases of urodynamically proven muscle dysfunction associated with low flow.

Development of bladder control and etiology of LUTD

Mechanism of urinary control in infants is not fully understood; however, it is postulated that micturition is controlled largely by the pontine mesencephalic micturition center. Volitional control starts in children aged around 1 year, when the cortical pathways begin to develop that inhibit the brainstem. This development allows children to achieve full continence at around age 3 to 4 years.

Frequency is considerably different in children when compared with adults due to the latter’s maturation of the bladder and continence mechanism. As children age, the bladder capacity and voluntary control of the external sphincter increases. This change results in a decrease in frequency of voiding from up to 24 times a day in infants to around 4 to 6 times in normal adults. The change to adult voiding patterns occurs around the age of 4. Normal increase in bladder capacity is calculated by the formulas :

Disturbances to normal bladder function in a child without neurologic lesions have been theorized to be largely behavioral in origin. The ability of the central nervous system (CNS) to cause a functional obstruction by volitional contraction of the external sphincter has been well recognized since Hinman and Baumann first described the functional discoordination between detrusor contraction and the external sphincter. Evidence that stressors during or after toilet training can lead to LUTD that may perpetuate infantile voiding patterns supports this theory. Sexual abuse, especially in female patients, has been linked to new onset of DV. In addition, children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have higher rates of DV.

As a result of studies of DV diagnosed in infancy, a congenital or genetic component to the disorder has been postulated recently. Small series of infants with signs and symptoms consistent with nonneurogenic neurogenic bladder (NNNB) syndromes have been reported. Furthermore, DV has been linked to the Ochoa syndrome, a genetic disorder with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. The gene locus at chromosome 10q23-q24 is identified as the defective gene in Ochoa syndrome. It is postulated to be the possible gene locus of the NNNB described by Hinman and Allan. This information casts doubt on the commonly held belief that disturbance of behavior is the sole cause of NNNB because these findings are present at or near the time of birth.

Animal and human studies have supported the evidence of a multifactorial cause of DV that involves complex interplay of the nervous systems and end organs. This has been referred to the neuroplastic model of DV in which adverse neural remodeling of the bowel and bladder occurs due to an unidentified trophic factor released in response to pelvic floor activity. Steers and De Groat demonstrated in a rodent model that obstruction of the urethra leads to an exaggerated spinal reflex contributing to bladder instability and hypertrophy. Yamanishi and colleagues have shown that the modulation of the CNS influences overactive bladder symptoms. Their work on intractable overactive bladder symptoms with biofeedback has shown that the CNS can modulate bladder activity once thought to be largely reflexive in nature. The hypothalamus has been shown to have feedback of neurons from the pelvic nerve that has stimulatory and inhibitory activity on the bladder. Electrostimulation of the anterior hypothalamus stimulates bladder contraction, and electrostimulation of the posterior hypothalamus has been shown to be inhibitory. Modification of the peripheral nervous system through selective dorsal root rhizotomy has led to improvement of urodynamic parameters in patients with spastic cerebral palsy. In addition, stimulation of peripheral afferent neurons leads to an inhibitory effect of detrusor through inhibition of the dorsal horn. Finally, visceral afferent input to the detrusor muscle can be modified through cervical and rectal stimulation. Together, these findings support the theory that LUTD may not be fully explained by disturbances of behavior alone. The complex interplay of pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) that leads to end-organ changes through abnormalities in neural networks is yet to be fully elucidated.

Development of bladder control and etiology of LUTD

Mechanism of urinary control in infants is not fully understood; however, it is postulated that micturition is controlled largely by the pontine mesencephalic micturition center. Volitional control starts in children aged around 1 year, when the cortical pathways begin to develop that inhibit the brainstem. This development allows children to achieve full continence at around age 3 to 4 years.

Frequency is considerably different in children when compared with adults due to the latter’s maturation of the bladder and continence mechanism. As children age, the bladder capacity and voluntary control of the external sphincter increases. This change results in a decrease in frequency of voiding from up to 24 times a day in infants to around 4 to 6 times in normal adults. The change to adult voiding patterns occurs around the age of 4. Normal increase in bladder capacity is calculated by the formulas :

Disturbances to normal bladder function in a child without neurologic lesions have been theorized to be largely behavioral in origin. The ability of the central nervous system (CNS) to cause a functional obstruction by volitional contraction of the external sphincter has been well recognized since Hinman and Baumann first described the functional discoordination between detrusor contraction and the external sphincter. Evidence that stressors during or after toilet training can lead to LUTD that may perpetuate infantile voiding patterns supports this theory. Sexual abuse, especially in female patients, has been linked to new onset of DV. In addition, children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have higher rates of DV.

As a result of studies of DV diagnosed in infancy, a congenital or genetic component to the disorder has been postulated recently. Small series of infants with signs and symptoms consistent with nonneurogenic neurogenic bladder (NNNB) syndromes have been reported. Furthermore, DV has been linked to the Ochoa syndrome, a genetic disorder with an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. The gene locus at chromosome 10q23-q24 is identified as the defective gene in Ochoa syndrome. It is postulated to be the possible gene locus of the NNNB described by Hinman and Allan. This information casts doubt on the commonly held belief that disturbance of behavior is the sole cause of NNNB because these findings are present at or near the time of birth.

Animal and human studies have supported the evidence of a multifactorial cause of DV that involves complex interplay of the nervous systems and end organs. This has been referred to the neuroplastic model of DV in which adverse neural remodeling of the bowel and bladder occurs due to an unidentified trophic factor released in response to pelvic floor activity. Steers and De Groat demonstrated in a rodent model that obstruction of the urethra leads to an exaggerated spinal reflex contributing to bladder instability and hypertrophy. Yamanishi and colleagues have shown that the modulation of the CNS influences overactive bladder symptoms. Their work on intractable overactive bladder symptoms with biofeedback has shown that the CNS can modulate bladder activity once thought to be largely reflexive in nature. The hypothalamus has been shown to have feedback of neurons from the pelvic nerve that has stimulatory and inhibitory activity on the bladder. Electrostimulation of the anterior hypothalamus stimulates bladder contraction, and electrostimulation of the posterior hypothalamus has been shown to be inhibitory. Modification of the peripheral nervous system through selective dorsal root rhizotomy has led to improvement of urodynamic parameters in patients with spastic cerebral palsy. In addition, stimulation of peripheral afferent neurons leads to an inhibitory effect of detrusor through inhibition of the dorsal horn. Finally, visceral afferent input to the detrusor muscle can be modified through cervical and rectal stimulation. Together, these findings support the theory that LUTD may not be fully explained by disturbances of behavior alone. The complex interplay of pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) that leads to end-organ changes through abnormalities in neural networks is yet to be fully elucidated.

Classification of LUTD

Disturbances of the lower urinary tract function in neurologically normal children can be categorized by the bladder cycle. Problems related to the filling phase include overactive bladder syndrome, functional urinary incontinence, and giggle incontinence. Disturbances of the emptying phase include DV, lazy bladder syndrome, Hinman syndrome, and post-void dribbling. Confusion can occur in identifying these syndromes as they may exist as a single entity or in combination and can be progressive.

Overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome includes involuntary detrusor contractions and urethral instability. OAB has replaced “unstable bladder of childhood” in the ICCS definitions. This syndrome is found to coincide in a third of children with VUR and recurrent UTIs. In children, OAB is the result of sudden and overwhelming urge to void that requires immediate urethral compression by the pelvic floor or by external maneuvers such as the Vincent curtsy. This syndrome may also result in constipation from chronic pelvic musculature contraction. The diagnosis of OAB syndrome can be made on examining the history of incontinence related to urgency, and does not require urodynamic evidence of uninhibited detrusor activity.

Functional urinary incontinence is the failure of the sphincteric mechanism to maintain continence in anatomically normal children. True stress urinary incontinence in which there is an anatomic insufficiency of the sphincteric mechanism to hold urine in transmission of abdominal pressures to the bladder is rare in children.

Giggle incontinence is a rare disorder seen almost exclusively in female patients in which large-volume incontinence occurs with laughter. This disorder may represent a type of cataplexy, as methylphenidate has been shown to alleviate some of the symptoms in this disorder. Recently, PFMR has been shown to be a possible treatment method.

Dysfunctional voiding is an abnormal contraction of the voluntary sphincter mechanism during voiding that is thought to be an acquired disorder that may progress to complete loss of bladder function. Staccato and fractionated voiding are seen in these children in uroflow studies. Due to the abnormal contraction of the pelvic floor, constipation is common in these children. Dysfunctional elimination syndrome (DES) is often used to describe this disorder because this term accounts for the link between the difficulty in voiding and defecation caused by the abnormal contraction of the pelvic floor.

Lazy bladder syndrome is the loss of detrusor activity that requires the Valsalva maneuver to fully empty the bladder. Long-term fractionated voiding is thought to be the cause of this syndrome in which long voiding times result in loss of the normal detrusor function. Children often present with a history of infrequent large voids, and urodynamics may reveal large bladder capacity with low detrusor pressures and high abdominal pressures during voiding.

Hinman syndrome is often interchanged with occult neuropathic bladder and represents full decompensation of the voiding mechanism. Children will present with day and nighttime incontinence, chronic UTIs, and chronic constipation. Urodynamic studies will often show uninhibited detrusor activity during filling, high filling pressures, large post-void residual (PVR) volumes, and abnormal activity of the pelvic floor musculature during voiding. Imaging studies results are frequently abnormal with hydroureteronephrosis secondary to VUR being common.

Post – void dribbling is a disorder in which incontinence of urine occurs immediately after micturition. This syndrome is more common in female patients and is thought to be secondary to retained urine in the vagina that leaks after standing. This syndrome is generally thought to be harmless and resolves with age. It is best treated by having the patient sit backward on the toilet, causing the legs to spread widely apart. Once the child is able to void with a clear stream in this position, voiding can occur in a normal position.

Vesicoureteral reflux and UTI in LUTD

VUR in LUTD is theorized to be not the result of a short mucosal tunnel, but of high filling and voiding pressures. Whereas VUR in boys is typically detected prenatally by ultrasonography, VUR in girls is often detected at an older age with UTIs and DV symptoms. Children with PFD are more likely to have recurrent UTIs, have mild bilateral reflux with less spontaneous resolution, and are less likely to have success with surgical management.

VUR and UTI are not independent of DV, as found by Chen and colleagues. Surprisingly, DES was found more often in children with VUR and UTI, but presence of DES was not predictive of VUR. This is in line with the neuroplastic theory that postulates that hypertrophy of the bladder and bowel musculature is caused by trophic factors released during pelvic floor hyperactivity secondary to central nervous disturbances. Hypertrophy can lead to an increase in risk factors that predispose the urinary tract to more UTIs and more severe VUR including anatomic bladder abnormalities, constipation, increased residual urine, higher voiding pressures, and increased urethral bacteria colonization secondary to turbulent flow. Turbulent flow is of particular importance as eddy currents formed by nonlaminar flow leads to reflux of periurethral bacterial to the proximal urethra and bladder, causing recurrent infections.

The pelvic floor musculature is closely related to bowel and bladder. Isolated contraction of the pelvic floor musculature was found to lead to spontaneous contraction of the bladder. The cycle of PFD contributing to recurrent UTIs and VUR can cause worsening bladder and bowel symptoms, and increased PFD with functional obstruction. Eventually this can lead to a hypertrophied, small-capacity bladder with high-pressure voiding that will lead to renal damage. The integral relationship between the pelvic floor activity with UTIs and VUR can be used as a model for developing treatment strategies in affected children to address the cognitive and behavioral aspects of DV and prevent irreversible damage to the upper urinary tract.

Constipation and LUTD

According to the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (NASPGN), constipation is defined as “a delay or difficulty in defecation, present for 2 weeks or more, and sufficient to cause significant distress to the patient.” Constipation is a cofactor in PFD that contributes to voiding symptomatology, and should be factored into management programs. The close link between bladder and bowel function is evident in embryologic development with the formation of the pelvic floor where both organs empty to, and shared innervations of sacral spinal nerves. This link may be under-recognized by clinicians and parents who have children with wetting problems. In one study of children with enuresis, more than one-third of patients had constipation despite only 14% of parents reporting any difficulties with stooling.

Children with constipation may present with DV and suffer from high residual volumes and reflux due to distention of the bowel that inhibits normal contraction. Resolution of constipation has been identified as an independent risk factor in the management of VUR. Upadhyay and colleagues also showed that improvement in bowel-function scores on the Dysfunctional Voiding Symptom Score (DVSS) correlated directly with improvements in VUR. Treatment of constipation also decreases UTIs, most likely through modification of the bowel flora. Constipation and distention of the rectal vault can lead to obstruction of the urethra, which may be one reason why treatment of constipation reduces residual volumes of urine.

Evaluation

Children with DV typically present symptoms that start soon after toilet training. Children will often continue to have daytime or nighttime incontinence, or both. Initial examination of patient history should focus on relevant questions pertaining to frequency, daily patterns of voids, volume of voids, and symptoms of urgency. Fluid intake data including caffeine consumption can be elicited. Developmental history should focus on birth history, developmental milestones, age of toilet training, any troubles with toilet training, and behavioral or mental deficiencies. History of UTI and vesicoureteral reflux is also relevant. Social history should be assessed for any new stressors including recent move, interruption of home life, recent separation from loved ones, or school performance. Relevant questions pertaining to constipation, soiling, and encopresis should be assessed. Parents are often unaware of their child’s bowel habits, including abdominal pain or anxiety associated with defecation. Voiding diaries are useful to accurately record fluid intake, frequency, urgency symptoms, incontinence episodes, voiding patterns, and voiding volumes.

Physical examination should be focused and rule out any signs of neurologic deficits. Inspection of the back should focus on signs of spinal dysraphism or sacral agenesis. A neurologic examination to assess strength and reflexes of the extremities, gait, perineal sensation, rectal tone, and bulbocavernosal reflex is useful to reveal any neurologic deficit. Abdominal examination may reveal impacted stool in the colon. A genitourinary examination should focus on the urethral meatus to ensure patency. Perineal soiling or excoriation of the skin may be present as well as fecal staining of undergarments.

Laboratory assessment should occur at the initial visit and include a urinalysis with cultures and sensitivities. For children presenting with LUTD and recurrent febrile UTIs, ultrasonography of the kidneys and bladder with pre- or post-void volumes should be performed. The ultrasonographic scan can be assessed for thickened bladder wall, obstructive uropathy, or ureterocele. Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) is indicated in patients with documented UTIs. Significant findings include spinning top deformity in girls with DV, keyhole sign in boys with posterior urethral valves, VUR, ureterocele, and bladder trabeculation.

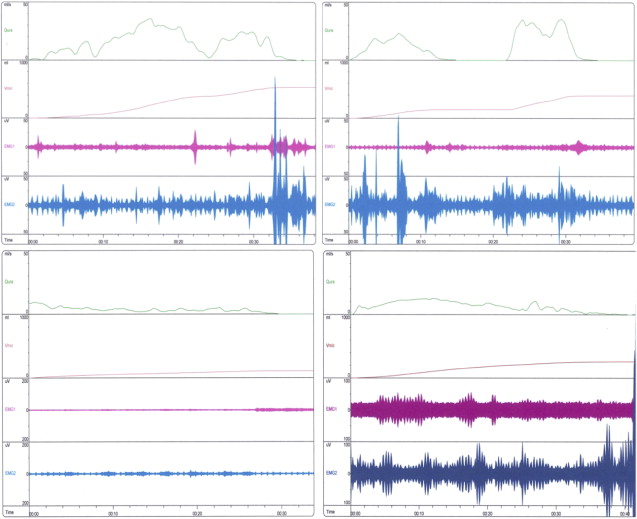

Full urodynamic studies are considered invasive and should be reserved for children with neurogenic bladder dysfunction, severe DV, or symptoms that do not improve with therapy. Less invasive uroflowmetry, perineal electromyography, and PVR comprise the preferred modality at the authors’ institution for screening and monitoring response to treatment. Before flow study, bladder ultrasonography is used to ensure adequate volume and exclude patients with overdistention of the bladder. Overdistention of the bladder can obscure results, causing an artificial increase in PVR volumes in normal children. A typical uroflow pattern in children with DV is a staccato pattern with a low prolonged flow rate. Children with detrusor underactivity will demonstrate low interrupted flows, abdominal straining, and large voided volumes ( Fig. 1 ).

In the evaluation of boys with OAB symptoms, anatomic abnormalities must be considered before the initiation of therapy. In flow studies, male patients may present with symptoms of frequency, urgency, or dysuria, and a flattened curve without pelvic floor activity. In a recent series from the authors’ institution, nearly 50% of these patients will have correctable surgical abnormalities including posterior urethral valves, strictures, or anterior urethral valves. Although the CNS is a major factor in OAB syndrome, these findings discount the theory that a CNS is the sole cause of OAB.

For assessment of constipation abdominal examination may used, but rectal examinations are generally not performed due to emotional distress of the child. Abdominal ultrasonography can be performed to diagnose and quantify constipation. An increased rectal diameter may indicate the diagnosis of impaction in some cases. This method may be useful in the management because a decrease in rectal diameter correlates with successful treatment. Bowel diaries and Bristol stool scales are also used to evaluate and monitor treatment in LUTD and constipation.

Recently, there has been an effort to standardize a scoring system in the evaluation of children with DV. This scoring system would be beneficial in classifying the type and severity of DV to determine necessary treatment modalities. A small prospective cohort was analyzed by Upadhyay and colleagues to determine the validity of the DVSS in children with reflux. A positive correlation between symptom score improvement and resolution of VUR was found. The validity of these scoring systems has not yet been evaluated in large prospective trials.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree