Phase I

Phone interview with transplant coordinator

Phase II

Evaluation by hepatologist, social worker, medical psychologist, and coordinator

Complete medical history and physical examination

Laboratory tests

Phase III

Surgical evaluation of donor

Preoperative anesthesia evaluation

CT/MRI to assess vascular/biliary anatomy

Other tests: based on results of initial testing

Presentation at liver transplant-selection conference

Phase IV

Final meeting with surgeon

Informed consent

The basic components of the evaluation process include

medical,

surgical, including radiologic, and

psychological and social.

Medical Evaluation

The purpose of performing a medical evaluation is twofold. The first is identifying an underlying medical disorder that would jeopardize the potential donor’s health; the second is to determine the suitability of the liver for transplantation, including screening for chronic liver disease and viral pathogens [8]. The initial part of this evaluation is similar to that of any patient undergoing a major abdominal surgery.

The initial screening of this evaluation can be performed by an experienced transplant coordinator, and often a phone interview is adequate. A general questionnaire includes obtaining information on age, height, weight, blood type, and a medical, surgical, and psychosocial history (including a history of alcohol and substance abuse). Potential donors with obesity and significant comorbidities can often be excluded at this stage. Age is an important screening variable at the initial encounter and potential donors falling outside the center’s accepted age criteria are excluded. The lower limit of age for donation is determined by the ability to give legal consent. The upper age limit for donation can vary from center to center but generally is between 55 and 60 years. Screening blood work can be performed at a center that is closest to the potential donor. Based on the results of the screening history and blood work, a potential donor is then brought to the transplant center for a complete evaluation.

The next phase of the evaluation begins with a complete history and physical examination by a physician. Individuals with significant underlying cardiac, respiratory, or renal problems are excluded from donation. Individuals with underlying risk factors for these specific organ systems (e.g., age > 40 and family history of cardiac disease) may require specialist consultation and tests. A more thorough and complete set of blood tests are now obtained assessing organ functions, potential risk factors (including risk of clotting), and potential for viral transmissions (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2

Blood tests obtained from the potential donor

Initial screen |

Complete blood count |

Serum electrolytes |

Renal function tests |

Liver function tests |

Lipid profile |

Blood type |

Viral serologic evaluation |

Hepatitis C |

Hepatitis B |

CMV |

EBV |

HIV |

Screening for thrombophilia disorders |

Protein C/S |

Antithrombin III |

Factor V Leiden mutation |

Prothrombin gene mutation |

Tests to exclude underlying chronic liver disease |

Serum transferrin saturation |

Ferritin |

α-1 Antitrypsin |

Other tests |

EKG |

Chest X-ray |

Special considerations include the following:

Donor obesity: Obese individuals are at an increased risk of surgical complications including bleeding, wound infection, and cardiopulmonary problems. The incidence of hepatic steatosis is greater in obese individuals. One study suggested that 78 % of potential donors with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 28 kg/m2 had over 10 % steatosis on liver biopsy [9]. However, not all studies have shown this degree of correlation. A BMI greater than 35 would exclude living liver donation for most centers. While many centers exclude donors with BMI > 30, a few selectively evaluate these donors and perform a liver biopsy to exclude hepatic steatosis [10].

Hepatitis B Core Antibody (HBcAb) positive donors: The concerns of using HBcAb positive donors are twofold—risk to the donor and risk of transmission to the seronegative recipient [11]. The proportion of donors who are HbcAb positive is variable. In Asia, over half of evaluated donors test positive, and results from these areas have shown that the risk to seropositive donors is not different from HbcAb-negative donors. A liver biopsy is performed in HbcAb-positive donors to exclude hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. The concerns for the recipient are similar to that of a deceased donor who is HbcAb positive. The risk to a seronegative recipient can be nearly eliminated by the use of appropriate hepatitis B virus (HBV) prophylaxis.

Evaluation for thrombophilia: Deep venous thrombosis with subsequent pulmonary embolism is a serious postoperative complication that can be potentially life threatening. Several cases of pulmonary embolism have been reported with at least one or two cases of mortality due to this complication. Known risk factors for thromboembolic complications include obesity, use of oral hormone therapy, older age, smoking, positive family history, and an identified underlying procoagulation disorder. These risk factors should be addressed during the evaluation process, including screening tests to identify a procoagulation disorder. Tests should include testing Factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene mutations.

Surgical and Radiological Evaluation

This component of the evaluation determines the surgical suitability of the potential donor and specifically whether the anatomy and size of the donor liver is suitable for donation.

Anatomy

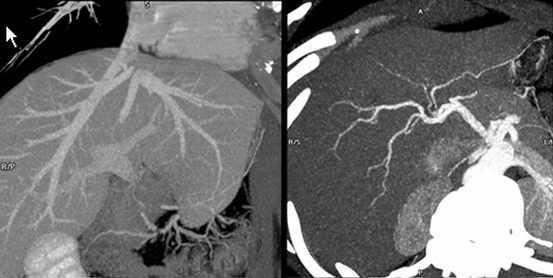

Evaluation of the vascular anatomy includes imaging of the hepatic artery, portal vein, and hepatic veins (Fig. 3.1). Most transplant centers routinely use computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with 3-D reconstructions as a single test [12, 13]. While some vascular variations may preclude donation, most can be handled with vascular reconstruction techniques. However, knowledge of these variations is important for operative planning and dissection. Possible vascular variations include a replaced or accessory left hepatic artery (LHA) or right hepatic artery (RHA), trifurcation of the main portal vein, and accessory hepatic veins. Depending on the planned liver resection, these anatomical variations may either have no impact or significantly complicate surgery.

Fig. 3.1

Vascular anatomy, including the hepatic veins, portal vein, and hepatic artery, can be determined with a single noninvasive test such as a CT scan with contrast

Some centers routinely obtain magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram (ERCP) as part of the evaluation to look at biliary anatomy. A CT cholangiogram may also be performed. These tests do not always provide the detail required, as a result of which many centers routinely perform an intraoperative cholangiogram.

Liver Volume

An accurate assessment of liver volumes is necessary to determine if the size of the transplanted liver graft is of adequate size for the recipient and if the size of the remnant liver is sufficient in the donor to prevent acute liver failure. A CT or MRI provides a reasonable estimate of the liver volume (Fig. 3.2). Most living donor transplants in adults are performed using the right lobe. Most centers prefer a graft weight to recipient weight (GW/RW) ratio greater than 0.8, or an estimate of graft weight as a percentage of standard liver mass exceeding 40 %. Smaller grafts may be associated with small-for-size syndrome and have worse outcomes.

Fig. 3.2

Determination of the volume of liver to be resected is an important component of the preoperative surgical evaluation and usually correlates well with intraoperative findings

The important concern in a pediatric recipient is not usually if the liver volume is too small, but rather too large. A large graft (GW/RW ratio >5 %) can cause difficulty in abdominal closure in the recipient. With regard to residual volume in the donor, an important part of the evaluation process is to ensure that the donor is not left with too small a liver volume. The donor should be left with at least 30 % of the measured total liver volume. The left lateral segment is most commonly used in pediatric recipients, and the adequacy of remnant liver size in the donor is not a concern. However, when a larger portion of the liver is removed (such as the right lobe), liver failure has been reported postdonation. There have been at least three reported cases of living donors in the US requiring an urgent liver transplant for liver failure after donation [14].

Liver Parenchyma

Some centers routinely biopsy all potential donors , while others biopsy only on a selective basis [15, 16]. The benefits of obtaining a liver biopsy are to assess for steatosis, and exclude chronic liver disease. Steatosis is more common in donors with a history of alcohol use, elevated triglyceride levels, higher BMI, or abnormal appearance on CT imaging. Some centers use these criteria to selectively biopsy the donors. Liver biopsy, with its risk for bleeding, remains an invasive test. Additional studies are needed to better define the role for liver biopsy. The presence of fibrosis, inflammatory changes, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and steatosis > 10–20 % (for right lobe liver donors) precludes donation. Steatosis identified on a predonation biopsy can be reversed with a program of dieting and exercise.

Psychological and Social Evaluation

This component of the evaluations assesses the potential donor’s willingness and competence to donate. It also ensures that the decision to donate is voluntary and free from coercion or inducement. It assesses the donor’s coping strategies and support structures. The formal part of this evaluation is multidisciplinary and is performed by a psychiatrist, psychologist or other mental health-care professional, and a social worker [17, 18]. There are several components to this part of the evaluation, which can be broadly divided into:

Mental health assessment: This includes obtaining a history of psychiatric disorders, substance abuse (if any), and assessment of competence to make the decision to donate.

Psychosocial history and assessment: This includes evaluation of life stressors, coping strategies, support structures, stability of living arrangements, finances, and work/school issues.

Motivation: The potential donor’s reasons for donation are determined, including an assessment to ensure that there is no coercion or inducement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree