Psychosocial Evaluation

The psychosocial evaluation is an important initial step in the evaluation of the potential donor (see also

Chapters 17 and

20). It also presents a valuable forum for fulfilling the tenets of informed consent, exploring donor motivation, and excluding coercion. Significant psychiatric problems that would impair the person’s ability to give informed consent or that might be negatively affected by the stress of surgery are considered contraindications to living donation (see

Chapter 17,

Table 17.4). The social support of the potential donor should be deemed adequate. The psychosocial evaluation of so-called nondirected or altruistic donors (see below) and donors who do not have a significant personal relationship with the recipient is particularly important because these donors may not enjoy the psychological gain of seeing the recipient benefit from their altruism (see

Chapter 17,

Table 17.1). Most donors can look forward to stable or improved sense of psychological well-being and can be told of such.

The psychosocial evaluation must consider the possibility of economic or other forms of coercion. The principles by which donors can be reimbursed for legitimate expenses incurred as a result of the donation or preparation for donation are addressed in the Declaration of Istanbul (see

Appendix) and in the National Organ Transplant Act (see

Chapter 18). In the United States, all medical costs directly associated with donation are covered by the health insurance of the recipient. The federal government and other employers provide for salary benefits for a 1-month period after donation, some states offer limited tax deductions for donation-related expenses, and a National Living Donor Assistance Center provides reimbursement of legitimate out-of-pocket expenses for

donors who can document financial need. There is no mechanism however, for routine reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses.

Medical Evaluation

Preliminary Laboratory Evaluation: Donor Typing to Determine the Risk for Acute Transplant Failure

Mandatory preliminary laboratory evaluation of a potential living donor includes determination of ABO blood group compatibility, crossmatching against the potential recipient, and HLA tissue typing. Because of the high costs of HLA laboratory testing and the availability of effective immunosuppressive therapy that minimizes the clinical significance of differences of HLA matching of living donors, some centers elect to perform HLA typing only in sensitized transplant candidates.

Which Donor to Choose?

In cases in which more than one donor is available, selection of the most appropriate donor depends on the degree of HLA matching and donor age. Biologically related donors are generally preferred over unrelated donors. When more than one family member is available, it is logical to commence evaluation of the

best matched relative (i.e., a two-haplotype match versus a one-haplotype match). If the donors have similar match grade (i.e., a one-haplotype-matched parent and a one-haplotype-matched sibling), it may be advisable to choose the older donor with the thought that the younger donor would still be available for donation if the first kidney eventually fails. When more than one one-haplotype-matched sibling is available, it may be worthwhile to check the tissue typing of one parent to determine which siblings shares the noninherited maternal antigens (see

Chapter 3). Such sharing may improve long-term graft survival.

It is often a good prognostic sign when the donor attends the recipient’s pretransplantation evaluation appointments. The initial approach to the potential donor should ideally come from the patient and not the patient’s nephrolo-gist, transplant physician, or surgeon. In cases in which patients hesitate to approach family members, the nephrologist and transplant team should be prepared to facilitate the discussion of donation. Written material explaining the donation process can often help to alleviate the fears and anxiety of potential donors. Excellent educational material is available on the websites of major nephrology and transplant-related organizations. Educational material that is home-based and culturally sensitive may be particularly effective.

Parents often are reluctant to turn to their children as potential donors, yet as those parents age, it becomes less and less likely that a donor from their own generation will be available. It is useful to point out to parents that their grown children are adults who are capable of making independent decisions; that the welfare of the donor will be protected in the evaluation and donation period; and that, if they exclude their children as donors, they may be preventing them from enjoying the psychological gain of helping a beloved parent. Older patients will often insist they would have been prepared to donate to their own parents while simultaneously expressing reluctance to permit their own children to donate to them.

Donor Age

Advanced age can increase the risk for perioperative complications, but there is no mandated upper age limit for living kidney donation. About 25% of programs in the United States exclude donors older than 65 years, and although many programs specify no upper age limit, donation after the age of 70 years is relatively uncommon. There is a trend toward using older donors, and the outcome of these donations, particularly to older recipients, is reported to be excellent.

With respect to younger donor age, most programs regard 18 years to be a firm lower age limit. Donors in their late teens and early 20s must be carefully evaluated for the maturity of their understanding of the donation process and to ensure they are not being subjected to overt or covert pressure. Their long life span and hence exposure to the risk for renal disease must be considered, particularly when there is a potential element of heredity in the etiology of the recipient’s renal disease.

Challenges in the Counseling of Older Transplant Recipients

Nearly 10% of all living donations are to recipients who are older than 65 years. Transplantation of living donor kidneys into recipients older than 70 years of age can be practically and ethically challenging. The elderly transplant candidates may be faced with a difficult dilemma: to wait for many years for a deceased donor kidney with the knowledge that their medical condition may continue to deteriorate, or to resort to a young family member for kidney donation while they are still medically suitable for the surgery and young and robust enough to enjoy the transplant.

When the potential donor is considerably younger than the recipient, the following questions should also be addressed: Is it reasonable to transplant a kidney from a very young donor into an elderly recipient who will only benefit from the kidney for a very limited number of years? Should the anticipated extra years of life gained by the recipient place any limitations to the living donor transplantation? There are no formal guidelines that address the acceptable age disparity between living donors and recipients. In most cases, it is best to leave the decision in the hands of an educated and informed potential donor.

Nonetheless, when an elderly transplant candidate does consider a living donor transplant, it is advisable that the transplant be performed as early as possible to maximize the benefit of the procedure. Furthermore, transplantation within a timely period has been shown to increase overall life expectancy, quality-adjusted life expectancy, and comorbidities for transplant recipients of all ages, whereas prolonged waiting time greatly decreased the clinical and economical benefit of transplantation.

General Assessment

The universal medical goals in the kidney donation evaluation process are to ensure that the potential donor has the following characteristics:

Is sufficiently healthy to undergo the surgical procedure

Has normal kidney function with minimal future risk for kidney disease

Represents no risk to the recipient in terms of communicable disease or malignancy transmission

Is not at increased risk for medical conditions that might require treatments that could endanger his or her residual renal function

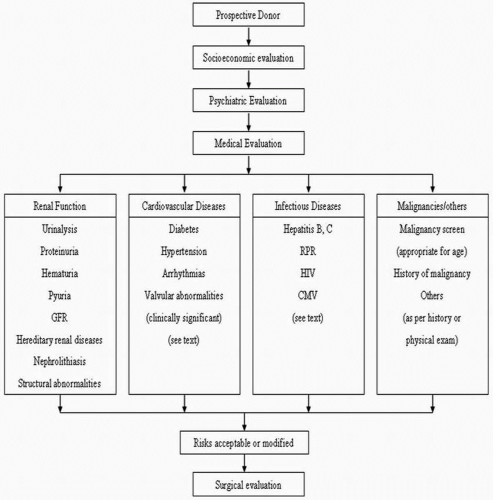

History, Physical Examination, Laboratory Testing, and Imaging

Living donor evaluation requires a thorough history and physical examination supplemented by laboratory testing, age-appropriate medical screening, and renal imaging (

Table 6.3). Donor history or characteristics known to confer significant risk to either the donor or recipient can automatically preclude donation. Obvious contraindications should be determined at the beginning of the donor assessment before subjecting unqualified donors to unnecessary tests (

Table 6.4). Female patients should not be evaluated while pregnant or planning to become pregnant in the immediate future. The appropriate postpartum time when donor evaluation may be resumed has not been determined, but if the donor so desires, it is reasonable to evaluate for donation 6 months postpartum. Desire for future pregnancy does not contraindicate donation. Unilateral donor nephrectomy does not increase obstetrical risks or complications.