ESSENTIAL CONCEPTS

ESSENTIAL CONCEPTS

Hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma are among the leading indications for liver transplantation in the United States.

Thorough medical, psychiatric, and social evaluation is required prior to listing patients for transplantation.

The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score is widely used for prioritizing patients on the transplant waiting list.

Liver biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis of acute rejection, which is common and occurs in up to 60% of patients.

Surgical complications generally occur within days to weeks and medical complications months or years later.

Biliary strictures and leaks occur in 15% of patients after transplantation.

Long-term immunosuppression, with calcineurin inhibitors, is associated with an increased risk of renal failure.

Liver transplantation has radically changed the management of patients with chronic liver disease and acute liver failure. Following the first liver transplant procedure in 1963, numerous medical, surgical, and technical breakthroughs were required before transplantation became a viable therapy in liver disease. The 1-year survival rate remained low at 25% until the introduction of cyclosporine as a long-term immunosuppressant in the 1980s. Improvements in patient selection, further refinements in surgical techniques, additional immunosuppressive agents including mycophenolate mofetil, sirolimus, tacrolimus, azathioprine, and effective anti-infective treatment and prophylaxis, have resulted in 5-year survival rates of up to 85–90%.

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) is a nonprofit scientific organization based in Virginia that is responsible for matching donors to recipients and coordinating the organ transplantation process. UNOS has divided the United States into 11 regions to facilitate organ allocation (Figure 51–1).

INDICATIONS FOR TRANSPLANTATION

There are numerous indications for liver transplantation; common and uncommon indications are listed in Table 51–1.

| Common | Uncommon |

|---|---|

Chronic hepatitis B Chronic hepatitis C Autoimmune hepatitis Alcoholic liver disease Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease Primary biliary cirrhosis Primary sclerosing cholangitis Hepatocellular carcinoma Acute liver failure | Hereditary hemochromatosis Wilson disease α1-Antitrypsin deficiency Glycogen storage disease Tyrosinemia Urea cycle defects Amyloidosis Hyperoxaluria Branched-chain amino acid disorders Cystic fibrosis Alagille syndrome Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis Polycystic liver disease Budd-Chiari syndrome Metastatic neuroendocrine tumor |

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) infects approximately 170 million people worldwide and up to 4 million people (1–1.5%) in the United States. Based on histopathologic studies, it is believed that 5–20% of patients with hepatitis C develop cirrhosis after 20 years of infection. After the occurrence of cirrhosis, decompensation (ie, variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy) occurs in 25–28% of patients in a median of 3–9 years. HCV significantly contributes to the occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Current studies suggest that the 5-year incidence of HCC is 17–30% in HCV-induced cirrhosis per year.

Hepatitis C is one of the leading indications for liver transplantation in most countries, including the United States, accounting for up to 40% of transplant procedures performed each year. It is expected that the proportion of liver transplants resulting from HCV will increase over the next 10–15 years in response to increases in the incidence of cirrhosis and eventual decompensation or occurrence of HCC.

[PubMed: 12425564]

[PubMed: 17400322]

Until approximately 15–20 years ago, transplantation of patients infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) was controversial. The near universal recurrence of hepatitis B generally resulted in early graft loss. A major advance in the field of transplantation was the introduction of hepatitis B immunoglobulin and antiviral therapy with nucleoside and nucleotide analogs. This has resulted in a dramatic improvement in transplant outcomes, and HBV infection is now a well-accepted indication with a good prognosis.

Although less prevalent than HCV in the United States, HBV remains a common cause of decompensated liver disease and HCC globally. Approximately, 350 million people globally and 730,000 people in the United States are infected with HBV. The occurrence of cirrhosis is a significant prognostic indicator, with a 50% 5-year survival among patients with hepatitis B e antigen–positive disease and cirrhosis. Both the incidence of decompensation and HCC rate are slightly lower for HBV than for HCV. Although in the United States the number of transplant procedures performed because of HBV is small, it remains an indication in a large proportion of transplants performed in many Asian and European countries.

Alcoholic liver disease is the most common cause of cirrhosis in the United States and results in an estimated 12,000 deaths annually. Although there is concern that patients with alcoholic liver disease are high-risk candidates for poor outcomes after liver transplantation, graft loss as a result of alcohol abuse is uncommon. In fact, the 7-year graft survival rate is very good, and better than rates reported for many other indications for liver transplantation. Presently, approximately 85% transplant centers recommend a 6-month period of abstinence from alcohol before considering a patient for liver transplantation. This stipulated period of abstinence remains unproven as there are no conclusive data to suggest that any period of abstinence is associated with a decreased risk of relapse after transplantation. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommends careful assessment of such patients by a health care professional experienced in the management of patients with addictive behavior.

Liver transplantation has been used effectively to treat several genetic and metabolic diseases associated with liver involvement (see Table 51–1).

Hemochromatosis is primarily a disease of Caucasians, with a prevalence of 1 in 200–300 persons. Among patients with untreated hemochromatosis, a significant proportion can develop decompensated cirrhosis or HCC. For these patients, liver transplantation is a treatment option. The survival of patients who undergo liver transplantation for hemochromatosis is not comparable to that of patients with other genetic or metabolic liver disease treated with transplantation. This may be attributable to the presence of cardiomyopathy in patients with hemochromatosis. Among genetic and metabolic conditions, hemochromatosis is the most common reason for transplantation.

This autosomal-recessive condition is a common indication for liver transplantation in children. Patients who do not develop liver disease as children can develop cirrhosis, which tends to occur in the sixth and seventh decades. The outcomes for liver transplantation in this setting are very good.

Wilson disease is an autosomal-recessive disease that can cause either acute or chronic liver disease. In patients with fulminant failure or decompensated cirrhosis, liver transplantation is an effective therapy with a good prognosis. Transplantation cures the defect in copper secretion, and long-term antichelating therapy is generally not required.

A significant proportion of patients with autoimmune hepatitis develop decompensated cirrhosis despite immunosuppressant therapy. In patients with decompensated disease, liver transplantation remains a viable option; excellent survival outcomes and 5-year survival of 90% are reported.

Similarly, primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis are excellent indications for liver transplantation, and are associated with good graft survival.

Because of the increased risk of HCC in cirrhosis, most patients undergo some form of screening, which includes radiologic imaging or α-fetoprotein assessment, or both (see Chapter 50). The use of screening has resulted in the earlier detection of tumors. This has improved survival in HCC, especially in patients with small tumors. The AASLD and UNOS endorse liver transplantation as effective treatment for patients with “early HCC,” defined as a solitary tumor less than 5 cm or three tumors less than 3 cm. The 5-year survival rate in this group of patients has been reported to be 70%. In 2005, UNOS also allowed patients who meet either of these criteria to receive a higher MELD score at the time of being placed on the transplant list to increase the chance of receiving a liver transplant sooner.

Patients with HCC tumor burden just outside UNOS criteria have been shown to successfully undergo liver transplantation with careful patient selection. To meet University of California San Francisco (UCSF) or extended criteria, there can be one lesion not greater than 6.5 cm or upto three tumors but none greater than 4.5 cm. The total tumor volume cannot be greater than 8 cm. For patients who successfully undergo downstaging the HCC from UCSF criteria to Milan criteria and then undergo liver transplantation, the 5-year survival is approximately 80%.

[PubMed: 15057740]

Acute liver failure is a rare but life-threatening event that in many cases may result in death without a liver transplant. A detailed review of liver transplantation in acute liver failure is provided in Chapter 39.

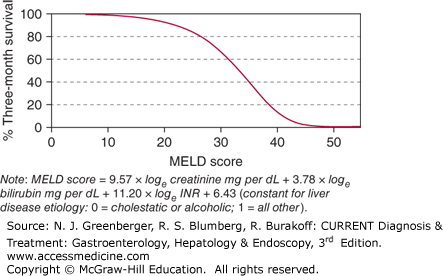

Since 2002, UNOS has used the MELD score to determine the need for liver transplantation in patients with cirrhosis. As shown in Figure 51–2, the 3-month survival of patients decreases with higher MELD scores. Many transplant centers use a MELD score of 15 as a minimal listing threshold. However, there continues to be a role for the Child-Pugh score (Table 51–2). Patients with Child class B or C cirrhosis have poor survival compared with patients who have more compensated Child class A disease. In addition, patients with a history of variceal hemorrhage and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis have decreased 1-year survival and would benefit from liver transplantation.

Figure 51–2.

Estimated 3-month survival as a function of the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. INR, international normalized ratio. (Adapted, with permission, from Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R, et al; for the United Network for Organ Sharing Liver Disease Severity Score Committee. Model for end-stage liver disease [MELD] and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology. 2003 Jan;124(1):91–96.)

[PubMed: 17326206]

One of the major goals of liver transplantation is to improve patients’ quality of life. Studies have shown that prior to transplantation, many patients experience significant impairments because of physical and emotional stress. A number of studies have shown that the quality of life for patients improves after liver transplantation.

PRETRANSPLANT EVALUATION

The evaluation of patients who are candidates for liver transplantation occurs in a multidisciplinary setting and involves hepatologists, transplant surgeons, anesthesiologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and subspecialists as needed.

Several diagnostic tests and procedures are used to evaluate patients; these are listed in Table 51–3 and described later.

Viral hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E serologies HIV testing Serologic testing for cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus immunoglobulin G Chest radiograph Pulmonary function tests with arterial blood gases Electrocardiogram Dobutamine stress echocardiography Magnetic resonance imaging and angiography of the liver Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy Cervical cancer screening Mammogram Prostate-specific antigen assay Dental evaluation Vaccination against hepatitis A and B, Pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, influenza Purified protein derivative skin test for tuberculosis Comprehensive psychiatric and social assessment |

Laboratory evaluation provides information about the underlying liver disease and assessment of liver and renal function (see Table 51–3).

Importantly, evaluation of the risk of developing complications related to immunosuppression is needed. Routine studies include serologic testing for cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Testing for histoplasmosis, schistosomiasis, and strongyloidiasis should be considered in patients from endemic areas. All patients should undergo skin testing for tuberculosis with purified protein derivative (PPD) and, if positive, further imaging of the chest. Further testing and referral to a pulmonologist or infectious disease specialist may be needed if the suspicion of tuberculosis remains.

Cardiac and pulmonary complications of liver transplantation are leading causes of mortality. Meticulous cardiopulmonary evaluation is required in every patient being considered for liver transplantation. The maximum heart rate achieved during dobutamine stress echocardiography and MELD score have been shown to adequately identify patients who would be at increased risk for cardiac mortality up to 4 months after transplantation. A recent study showed a high specificity and negative predictive value for dobutamine stress echocardiography at 98% and 89%, respectively. An added benefit of this test is that it can identify patients with congenital abnormalities of the heart such as a patent foramen ovale. If abnormalities are identified, they can be corrected and patients reconsidered for transplant.

[PubMed: 16555336]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree