CHAPTER 2 LIVER RESECTION

INTRODUCTION

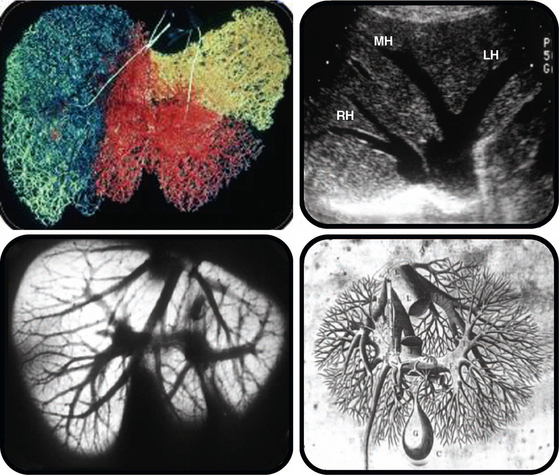

Partial hepatectomy is possible because liver regeneration is rapid (Plate 1) and because the liver is segmental in structure (Plate 2).

Hepatic resection for removal of lesions of the liver may be necessary for a wide variety of conditions (Table 2-1).

TABLE 2-1 Most Common Conditions for Which Liver Resection May Be Used for Therapy

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

PRINCIPAL HAZARDS

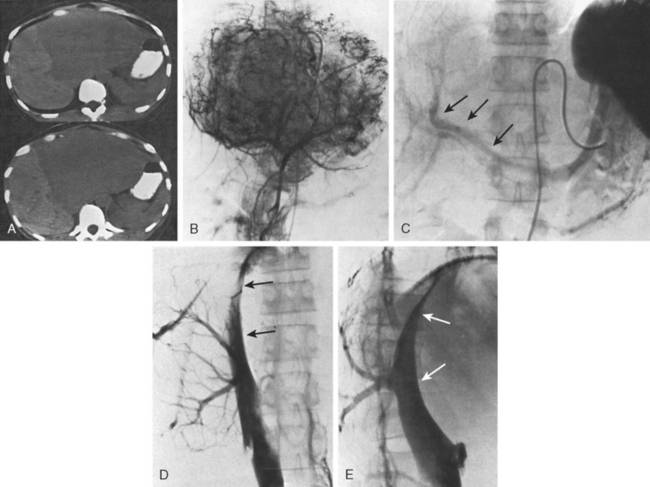

The main hazards of hepatic resection are biliary leakage and bleeding. Biliary leakage is a particular problem with patients in whom biliary reconstruction is necessary. Bleeding from the hepatic veins and the inferior vena cava (IVC) during parenchymal transection is a major concern. Bleeding is especially likely to occur during major resection for high and posteriorly placed tumors (Fig. 2-1).

SUMMARY

BASIC TECHNIQUES

ANATOMY AND CLASSIFICATION

The liver is divided into sectors that are formed from liver segments supplied by branches of the portal triads and drained by hepatic veins (see Chapter 1). Partial hepatectomy involves removal of one or more segments accomplished by isolation of the relevant portal pedicle, severance of the relevant hepatic veins, and removal of the associated liver tissue.

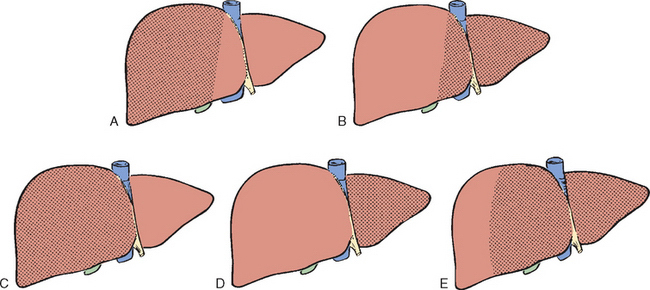

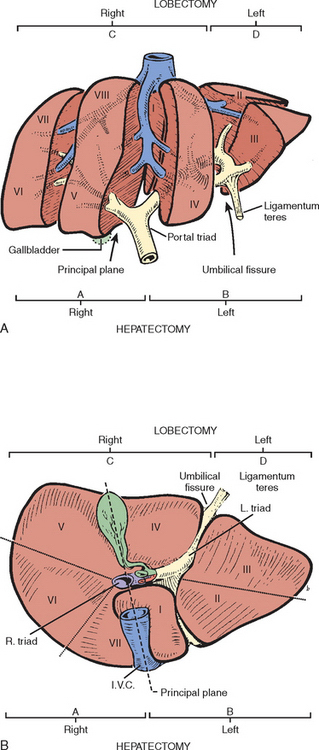

Essentially there are five types of major resection (Figs. 2-2 and 2-3). The nomenclature of these operations is based on the anatomic descriptions of Couinaud (1954, 1957) and Bismuth (1982) (Table 2-2). The alternative, more commonly used terminology of Goldsmith and Woodburne (1957) also is listed. A newer terminology has been proposed by the International Hepato-Pancreatico-Biliary Association (Strasberg et al., 2000), but it is not used in this text or in the narrative supporting the videos.

Figure 2-2 A, Exploded view to show the sectors (separated by the major hepatic veins) and the segmental structure of the liver, each segment supplied by a portal triad. The blood supply to segment IV is recurrent as feedback vessels. B, Inferior surface of the liver. Segment VIII is not seen because it lies superiorly. The anatomic division into right and left lobes by the umbilical fissure and into a right and left liver in the principal plane (along the principal scissura) is evident (see Chapter 1).