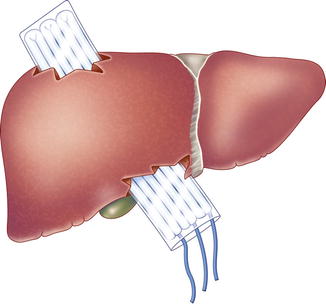

Fig. 12.1

A folded plastic drape is placed between the surface of the liver and the folded dry laparotomy pads used as perihepatic packing (a) anterior view (b) saggital view (Adapted from Feliciano et al. [20]. Used with permission)

Perihepatic packing placed directly over the liver anterior to the suprarenal and retrohepatic inferior vena cava can lead to compression of these structures. This compression can potentially collapse the renal veins and contribute to an abdominal compartment syndrome or be a direct cause of acute kidney injury. The risk of this secondary insult is surely increased in patients with recent hemorrhage and hypovolemic shock. In almost all patients with injuries crossing hepatic segments V, VIII, and IV, every effort should be made to place perihepatic packs either laterally or medially and direct posterior pressure in an oblique fashion. Avoiding direct posterior compression at a pressure greater than 30 mmHg in this location should prevent collapse of the renal veins [36].

Perihepatic compression from packs is lost in patients in whom the abdomen is left open under a silo or vacuum suction device. For this reason, it is appropriate to towel clip the skin edges of the upper 1/3 of the midline abdominal incision in patients in whom the rest of the abdomen will remain open. This will maintain the tamponading effect of the perihepatic packs in such patients and, if performed properly, should still avoid causing an abdominal compartment syndrome.

Other Techniques

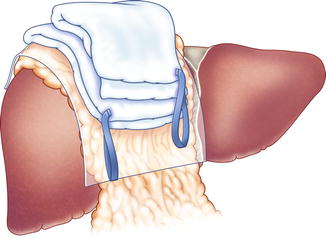

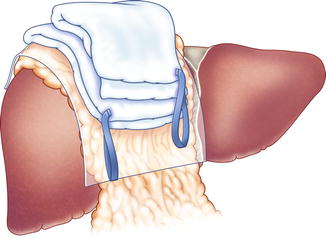

In 1994, McHenry et al. [33] described an approach to packing that combined the use of intrahepatic omental packs and current perihepatic approaches [37]. After selective intrahepatic ligation of major vessels and segmental bile ducts, a mobilized piece of viable omentum is placed into the hepatic defect. This is covered with a nonadherent plastic drape, and perihepatic packs are placed anterior and posterior to the liver (Fig. 12.2). At the time of reoperation, the perihepatic gauze packs and plastic drape are removed. The omentum is left in place in the hepatic defect without suturing, perihepatic drains are inserted, and the midline incision is closed.

Fig. 12.2

Intrahepatic omental packing is covered with a plastic drape and laparotomy pads are placed above this for compression (Adapted from McHenry et al. [33], Copyright 1994, with permission from Elsevier)

Another variation of the old technique of intrahepatic packing was reported by Ong et al. [38] in 2007. In a patient on anticoagulants who sustained a gunshot wound from the “dome of the right lobe” to the inferior surface of “segment IV”, a large “tunnel” was left in the liver. Because of ongoing hemorrhage, a plastic bowel bag was inserted through the “tunnel” in the liver. Three laparotomy pads were then placed into the bag creating intrahepatic tamponade (Fig. 12.3). At the time of relaparotomy, the laparotomy pads were removed from the intrahepatic bag. Bleeding did not recur over a period of 20 min, and the plastic bag was removed.

A “refinement in the technique of perihepatic packing” has been described by Baldoni et al. [34] from Bologna, Italy, in recent years. The right lobe of the injured liver is completely mobilized by division of the right triangular and anterior right coronary ligaments. Laparotomy pads are then packed around the posterior paracaval surface (without compressing the retrohepatic inferior vena cava [36]); the lateral right lobe, anterior to the lobe; and posteroinferior to the lobe. The authors’ comparison of results in patients with grades IV–V injury using an older technique of packing in 23 patients from 1996 to 2004 versus the “refined” technique described above in 12 patients from 2005 to 2008 is in Table 12.1. The authors have continued to analyze their results with this newer approach [39].

Table 12.1

Comparison of the results in two groups of patients treated with the old and “refined” perihepatic packing

Old technique 1996–2004 | “Refined” technique 2005–2008 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

# Patients | 23 | 12 | – |

Grade IV/V | 16/7 | 9/3 | .260 |

Base deficit on arrival | −10.7 | −8 | .200 |

Liver-related complications | 41.7 % | 18.2 % | 0.97 |

Intra-abdominal sepsis | 41.7 % | 9.1 % | 0.076 |

Death within 24 h | 52.2 % | 8.3 % | 0.01 |

Overall survival | 30.4 % | 75 % | 0.015 |

Removal of Perihepatic Packing

In the past, there was a technique of bringing long gauze perihepatic packing out of a hole in the lateral abdominal wall at the first operation. The intent was to allow for subsequent removal of the packing without a relaparotomy. This technique has been slowly abandoned over the past 35 years as rebleeding was common, missed injuries could not be searched for, and the abdomen could not be irrigated.

The need for a relaparotomy, however, has its own “side effects.” It mandates a return trip to the operating room, a second general anesthetic, and a further manipulation of the injured liver and edematous midgut, and it may cause a “second hit” phenomenon [40]. Therefore, the timing of a relaparotomy would appear to be a critical decision for the trauma surgeon. Unfortunately, little scientific evidence exists to support any postsurgery day as being ideal for all patients.

In the 1981 review of ten patients by Feliciano et al. [17], perihepatic packing was removed from 8 h to 10 days (mean 5.2 days). The patient with the longest delay till pack removal developed severe respiratory failure and anuric renal failure after the first trauma laparotomy. A second review of 49 patients from the same group in 1986 described the timing of removal as being based on the patient’s condition: “Patients without evidence of further bleeding are returned to the operating room for pack removal when the cardiovascular system is stable, coagulopathies have been corrected, and only the respiratory system is being supported” [20]. The authors noted that the timing of pack removal depended on the timing of insertion of the packing, as well. In 22 patients who survived after perihepatic packing was inserted at the first trauma laparotomy, removal of the packing was performed at a mean of 3.3 days. The six patients who survived after perihepatic packing was inserted at a reoperation (continuing hemorrhage; ruptured subcapsular hematoma) had removal of the packing performed at a mean of 5.5 days. Of interest, later postoperative intra-abdominal fluid collections, hematomas, or abscesses occurred in 9 of the 47 patients (18.4 %) surviving the first trauma laparotomy in this review. Five of the ten drained collections in these nine patients were purulent for a 10.2 % incidence of perihepatic abscess.

Another approach was used by Carmona et al. [19] in the early 1980s. In a review of 17 patients who underwent temporary perihepatic packing: “The average time between the first and second operation was 17 h (range of 10–28 h) to remove the packs and reexplore the liver.” No rationale for such early removal of the packing was presented in the manuscript.

In the later review of patients with perihepatic packing by Krige et al. [41] from Cape Town, South Africa, the authors noted that “six of the 16 survivors in this series developed sepsis and one patient died of septicaemia; five of these seven patients had an associated bowel or biliary injury.” The authors recommended that patients with isolated hepatic injuries have removal of packing at 48 h “after correction of coagulation and metabolic abnormalities…in the liver injuries with gross bowel contamination or bile leaks…packs should be retrieved at relaparotomy within 24 h.”

One of the most helpful reviews with regard to timing of pack removal was by Caruso et al. [42] from the University of California, Davis, in 1999. In this interesting report, outcomes were compared between 39 patients who had perihepatic packing removed within 36 h of insertion and 24 patients who had packing removed 36–72 h after insertion. While rebleeding requiring repacking was significantly more common in the early pack removal group (early 21 % vs. late 4 %, p < 0.001), liver-related complications (early 33 % vs. late 29 %) and mortality (early 18 % vs. late 29 %) were similar.

Similar findings were noted in the review by Nicol et al. [43] from Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa, in 2007. Perihepatic packing was inserted in 17 % of all patients with hepatic injuries noted at laparotomy, and the mean duration of packing was 2.4 days. Early removal of packs at 24 h led to a higher rate of rebleeding when compared to the group of patients with removal at 48 h (p = 0.006). As in the review by Caruso et al. [42], the total duration of perihepatic packing (1 vs. 2 vs. 3 or longer days) had no impact on postoperative liver-related complications or the development of intra-abdominal collections.

In essence, “damage control” principles apply when considering the timing of removal of perihepatic packing. Hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathies should be corrected, and the patients should be in the “diuretic phase” of recovery from resuscitated hemorrhagic shock. Consideration should be given to an earlier return to the operating room (48 h) in patients with extensive gastrointestinal contamination noted at the first trauma laparotomy.

Complications

Complications related to perihepatic packing are difficult to distinguish from those due to the hepatic injury itself. For example, the earliest complication that might be attributed to perihepatic packing would be failure to control hepatic hemorrhage. This could be due, however, to failure of the surgeon to control intrahepatic arterial hemorrhage or delaying the insertion of packs till an intraoperative coagulopathy is well established. The former is the most likely cause of persistent post-packing hemorrhage in the modern era. For this reason, immediate postoperative hepatic arteriography with therapeutic embolization is indicated whenever the surgeon is aware that hepatic hemorrhage has not been fully controlled by the perihepatic packing. In the intensive care unit, continued hepatic hemorrhage is suggested by the need for continuing transfusion of two units of packed red blood cells per hour.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree