INTRODUCTION

The increased use of imaging modalities—ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—over the past few decades has led to an increase in the detection of hepatic masses. In patients without cirrhosis or a history of extrahepatic malignancies, most of these lesions are benign. Diagnosis is generally made on the basis of radiographic appearance, and only in rare equivocal cases histologic analysis is required. In patients with cirrhosis or those with chronic hepatitis B infections, the detection of a hepatic mass often raises suspicion of a hepatocellular cancer, and frequently additional diagnostic (including histologic) and therapeutic interventions may be necessary.

Liver lesions are often classified on the basis of appearance (cystic or solid) and histologic composition (hepatocellular or biliary). They can also be classified based on malignant potential (benign or malignant), and when, malignant, they can be classified based on origin of the cancerous cells (primary or metastatic). In adults, malignant tumors are more common than benign tumors and metastatic lesions account for most forms of liver neoplasms. The differential diagnosis of liver lesions includes benign lesions (eg, hemangioma, focal nodular hyperplasia, adenoma, focal regenerative hyperplasia, simple hepatic cysts, polycystic liver disease, bile ductular cystadenoma, and bile ductular hamartomas) and malignant lesions (eg, primary hepatocellular cancer, cholangiocarcinoma, metastatic tumors, lymphoma).

[PubMed: 19442914]

BENIGN LIVER TUMORS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Cavernous hemangiomas, focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatic adenomas, and nodular regenerative hyperplasia are the most common benign tumors of the liver.

Cavernous hemangiomas are usually asymptomatic and can be identified by their classic appearance on CT and MRI.

Focal nodular hyperplasia is common in young women and can be identified by the presence of a central stellate scar on CT or MRI.

Hepatic adenomas are common in women of childbearing age, especially after prolonged oral contraceptive use. Because necrosis, hemorrhage, or rupture can occur, they should be surgically excised when identified.

Nodular regenerative hyperplasia is associated with many systemic illnesses. Patients present with signs of portal hypertension. Radiographic characteristics are nonspecific, and histologic evaluation shows no fibrosis.

In clinical practice the most commonly encountered lesions are cavernous hemangiomas, focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), hepatic adenoma, and nodular regenerative hyperplasia.

[PubMed: 11933585]

This is the most common benign lesion of the liver, with a prevalence that ranges from 1% to 20% of the general population. Approximately two-thirds of all cavernous hemangiomas are found in the right lobe of the liver, and more than 90% are solitary. More than 80% occur in women. Although lesions can be small (often ≤1 cm), larger lesions, especially those greater than 4 cm (giant hemangiomas), also occur; some can be as large as 25 cm (Figure 50–1).

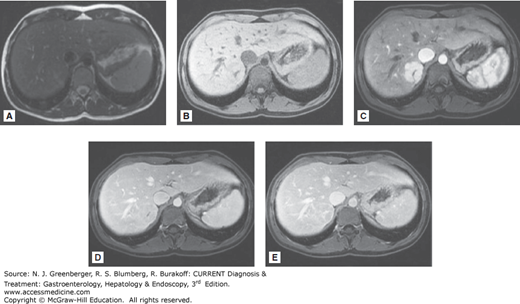

Figure 50–1.

Magnetic resonance images of a 25-cm giant hemangioma of the left hepatic lobe. The lesion is very bright on the T2-weighted image (A) but dark on the T1 precontrast image (B). Dynamic postgadolinium images show gradual nodular enhancement from the periphery to the center of the lesion on early arterial (C), late arterial (D), and delayed phase views (E). Arrows in B indicate the area of the hemangioma. (Used with permission of Dr Cheryl Sadow, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.)

Findings on laboratory evaluation are usually normal, but signs of portal hypertension such as thrombocytopenia may be noted in patients with very large hemangiomas. The diagnostic modalities available include ultrasound, CT, and MRI. Ultrasound has sensitivity of 60–70% and specificity of 60–80% for detection of hemangiomas. Because of nonspecific findings on ultrasound, contrast-enhanced CT or MRI is often necessary for diagnosis of cavernous hemangiomas.

On CT scan, the lesions are characterized by progressive enhancement during the arterial phase that begins at the periphery of the lesion and progresses inward. The intensity of enhancement during this arterial phase resembles that of the aorta. Small hemangiomas are difficult to diagnose on contrast-enhanced CT because of inability to detect the stepwise enhancement seen in larger lesions. Because of this apparent homogenous enhancement, they may resemble hypervascular liver masses. Overall, the sensitivity of contrast-enhanced CT for diagnosis of cavernous hemangiomas is estimated at around 90%, with specificity of around 90%.

On MRI, cavernous hemangiomas appear hypodense on T1-weighted images, hyperdense on T2, and with gadolinium they show the classic peripheral enhancement with progressive inward enhancement (see Figure 50–1).

Most cavernous hemangiomas are asymptomatic. They are usually discovered during abdominal imaging for unrelated symptoms. Treatment is usually not necessary, and there is often no need for continued surveillance. In the few instances where lesions are very large (>10 cm), symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and early satiety can occur. In these cases, surgical resection can be performed to alleviate symptoms.

A common benign lesion of the liver, FNH is seen in 0.9% of the population. It is the second most common hepatic lesion after cavernous hemangiomas. FNH is more common in women, occurring with a frequency of 8:1. Lesions are most often solitary, but approximately 20% of patients have multiple lesions.

The mechanisms underlying development of FNH are not well understood. It has been suggested that proliferation of hepatocytes secondary to vascular malformation or vascular injury may lead to FNH. Given the higher incidence in women, a correlative link has been made to the use of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). However, data suggesting a causative link or even the influence of OCPs on the growth of FNH are controversial. Indeed, many clinicians believe there is no link.

In more than 70% of patients with FNH, lesions are detected incidentally. In the remaining patients, symptoms (especially right upper quadrant discomfort) prompt evaluation. FNH can be classified into two broad categories: the more prevalent classic FNH, and the nonclassic FNH. Classic lesions are nodular, vascular lesions with bile duct proliferation. Radiographically, the lesions are often identified by the presence of a central scar; however, 95% of nonclassic lesions lack this feature. Histologically, the lesions are well circumscribed with proliferating hepatocytes and Kupffer cells. A central vascular scar is invariably present in the classic form of FNH.

Ultrasound can be used for the diagnosis of FNH. The central scar is seen on only 20% of ultrasounds. Doppler imaging shows increased blood flow with a pattern of abnormal blood vessels that emanate radially from a central feeding artery (“spoke-wheeling”). Because ultrasound is not considered the preferred diagnostic modality to rule out FNH, additional imaging with CT or MRI is usually the norm.

On contrast-enhanced CT, the lesion is isodense with the liver on precontrast and postcontrast images but shows homogenous enhancement during the arterial phase, along with the central scar (Figure 50–2). Figure 50–3 shows the typical MRI features of FNH. The lesion is isointense in T2-weighted images with a bright central scar (see Figure 50–3A). It is isointense or hypointense with a central dark scar on T1-weighted images (see Figure 50–3B), homogenously vascular except for the central scar in the arterial phase (see Figure 50–3C), isointense in the portal phase (see Figure 50–3D), and shows subsequent delayed enhancement of the central scar (see Figure 50–3E).

Figure 50–2.

Computed tomographic scans of focal nodular hyperplasia. The lesions are barely visible in the early arterial phase image (A) and not visible in the postvenous phase (C) but can be detected as two homogenous hypervascular images in the late arterial phase with contrast (B, arrows). A central scar is present. (Used with permission of Dr Cheryl Sadow, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.)

Figure 50–3.

Magnetic resonance images of focal nodular hyperplasia. The lesion is isointense with the liver on the T2-weighted image, but a bright scar is visible (A). On the T1-weighted precontrast image, the lesion remains isointense to slightly hypointense with liver, but a dark central scar is visible (B). Dynamic postgadolinium T1 image shows a homogenous hypervascular lesion except for a dark central scar (C). The lesion becomes isointense in the portovenous phase (D), with delayed enhancement of the central scar (E). Arrows indicate the location of the lesion. (Used with permission of Dr Cheryl Sadow, Department of Radiology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital.)

There is no indication to treat a patient with asymptomatic FNH because malignant transformation is not felt to occur with typical FNH lesions. Symptoms caused by FNH are present in 30% of patients. These patients often present with right upper quadrant pain. Surgical resection is indicated if patients have pain that is felt to be secondary to the FNH lesions, or if there is doubt about the diagnosis of FNH.

[PubMed: 10702207]

[PubMed: 10584697]

[PubMed: 10831693]

This rare liver tumor is most commonly diagnosed in women aged 20–40. The major risk factors are OCP use, glycogen storage diseases, diabetes, and androgen use. Among patients who use OCPs there is a 30-fold increase in prevalence of hepatic adenomas. Obese patients may be more likely to show progression in the neoplasms. The tumors are usually solitary and increase in size during states of enhanced estrogen levels, such as pregnancy and OCP use (see Figure 9–28). Of note, hepatic adenomatosis is a distinct entity from hepatic adenomas. Although the former syndrome is characterized by the presence of multiple hepatic adenomas, there is no association with OCP use, and it occurs equally in men and women. In addition, laboratory data usually show an elevated alkaline phosphatase level.

In approximately 20% of cases, hepatic adenomas are detected during radiographic imaging for unrelated issues in asymptomatic patients. However, many patients present with abdominal pain resulting from encroachment on neighboring tissue or overt hemorrhage of the tumor. Laboratory evaluation is usually normal in patients without hemorrhage. Histologic evaluation of hepatic adenomas often shows a circumscribed capsular tumor containing hepatocytes that appear normal but are architecturally distorted, in that bile ducts, portal venous tracts, and terminal hepatic veins are absent. The lesion often has a high fat and glycogen content, and necrosis and frank hemorrhage may be present.

Ultrasonographic evaluation can show a hyperechoic mass due to the intracellular fat, with areas that are hypoechoic as a result of hemorrhage. In the absence of contrast, CT usually shows a lesion hypodense to the liver parenchyma if there is no intramural blood. With contrast there is brisk, early enhancement as a result of the vascular nature of the tumor followed by an equally brisk washout due to arteriovenous shunting. On MRI, hepatic adenomas appear as hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted images (Figure 50–4A). On postgadolinium images, they show early arterial enhancement that rapidly washes out (Figure 50–4B and C).

Figure 50–4.

Magnetic resonance images of hepatic adenoma: T2-weighted images (A) show three heterogenous masses (arrows). Dynamic postgadolinium T1 images show early arterial enhancement (B and C) with washout in the delayed image (D). (Used with permission of Dr Koenraad Mortele, Department of Radiology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.)

Unlike the other benign hepatic lesions, hepatic adenomas produce significant associated morbidity. The lesion can lead to life-threatening hemorrhage resulting from tumor necrosis and rupture. In addition, hepatic adenomas have the potential for malignant transformation. Men are more likely to have a malignancy associated with hepatic adenoma possibly due to the presence of the metabolic syndrome. Although adenomas may be discovered incidentally, right upper pain resulting from encroachment on neighboring tissues or from necrosis can also occur. Shock from hemorrhage resulting from rupture is a life-threatening emergency that requires emergent resuscitation and surgical therapy. For symptomatic patients, surgical resection of the adenoma is the therapy of choice. OCPs can be stopped and lesions followed expectantly; however, such an approach is best in patients in whom surgical excision is not a valid option. Radiofrequency ablation has also be shown to a treatment option for hepatic adenomas in patients who are not surgical resection candidates.