(1)

Department of Endoscopy, Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital, Fukuoka, Chikushino, Japan

Summary

Light Blue Crest (LBC)

1.

Phenomenon that can only be visualized using NBI

2.

Fine light blue (light cyan colored) linear reflections located on the epithelial margins, visualized using M-NBI

3.

Indicator of the brush border of intestinal metaplasia

White Opaque Substance (WOS)

1.

Phenomenon that can be visualized using both WLI and NBI

2.

White opaque substance visualized by reflections/strong scattering of whole projected lights located in the surface epithelium of the IP.

3.

Nature is still unknown

Keywords

Intestinal metaplasia (IM)Light blue crest (LBC)Magnifying endoscopyStomachWhite opaque substance (WOS)10.1 Light Blue Crests (LBCs)

10.1.1 What Are LBCs?

The LBC is a specific phenomenon that can only be visualized using NBI. It was discovered by Uedo et al. and reported by them in 2005 [1]. The LBC is defined as “a fine, blue, white line on the crests of the epithelial surface/gyri” [2].

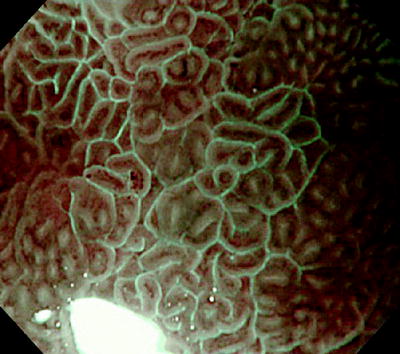

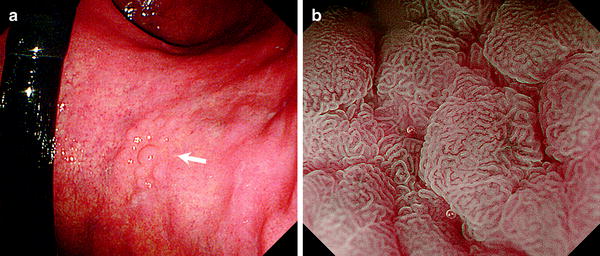

When we examine gastric mucosa with H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis using non-magnifying endoscopy with NBI, we sometimes see flat light blue mucosal areas. Examination of these areas using M-NBI reveals reflected light from light blue lines on the epithelial margins. This is the LBC phenomenon (Fig. 10.1). LBCs are reported to be useful indicators for the endoscopic diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia of the gastric mucosa.

Fig. 10.1

Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (M-NBI): image of intestinal metaplasia. We can see light blue (light cyan colored) linear reflections located on the epithelial margins (photograph kindly provided by Dr Noriya Uedo, of the Department of Gastrointestinal Medicine, Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases)

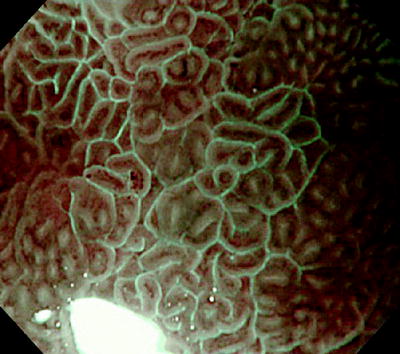

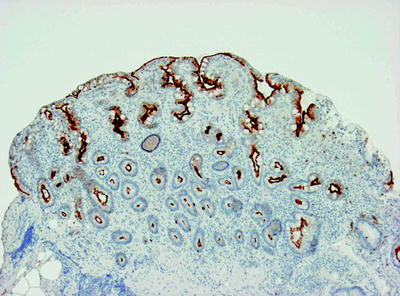

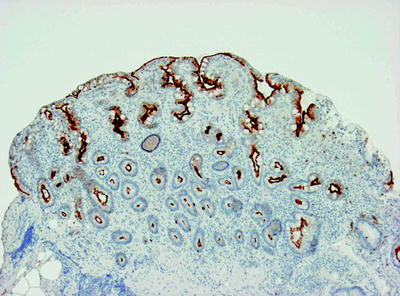

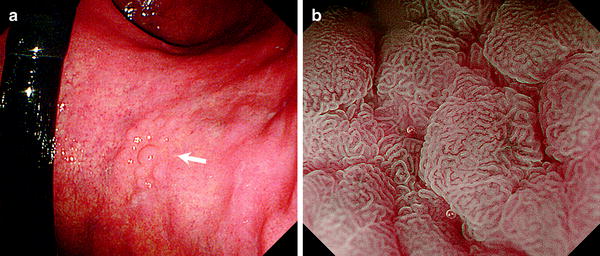

According to Uedo et al. [1], the frequency of LBCs correlates strongly with Alcian blue stained epithelium and the expression of immune staining CD 10. This confirms the LBC as an indicator of the presence of histological intestinal metaplasia with high accuracy and reproducibility (Fig. 10.2). Bio-optically, this phenomenon involves strong reflection of short wavelength narrow-band blue light (400–430 nm), with a central wavelength of 415 nm. We can infer that the short wavelength narrow-band light is reflected by the microvilli of the brush borders of the areas of intestinal metaplasia.

Fig. 10.2

Histological findings of biopsy specimen taken from the site shown in Fig. 10.1 (immune staining for CD 10). CD 10 (brush border) is strongly expressed in the surface layers of this intestinal metaplastic epithelium. We can understand that although the histological findings are of uniform CD 10 positivity of the intervening part epithelial surface, with magnifying endoscopy with NBI LBCs are lines located only on the margins of the crypts, visualized as lining the crypts. In other words, I believe that LBCs are short wavelength light reflected by microvilli aligned perpendicularly (photograph kindly provided by Dr Noriya Uedo, of the Department of Gastrointestinal Medicine, Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases)

The fact that a similar phenomenon is seen in the epithelial margins of the duodenal mucosa indicates that the above inference is reasonable.

10.1.2 Clinical Significance of LBCs

Although the clinical significance of LBCs has not yet been fully confirmed, there have been reports that demonstration of the presence of intestinal metaplasia in the gastric mucosa is useful in predicting coexistent atrophic gastritis and the risk of developing a differentiated carcinoma.

Tahara et al. [3] reported that when LBCs, particularly LBCs on the greater curvature of the gastric body, are observed using M-NBI, coexistent atrophic gastritis is also likely, and the risk of differentiated carcinoma is high. However, Uedo [4] stresses the importance of intestinal metaplasia of the gastric body, but the lesser curvature instead, as a risk factor for differentiated carcinoma. We await the results of further studies.

Clinically, LBCs lining the margins of intestinal epithelium associated with chronic gastritis are useful in evaluating the regular epithelial morphology. As will be shown in Chap. 12, the presence of regular LBCs is an extremely useful indicator that the microsurface pattern (S) is benign.

On the other hand, our studies have shown that LBCs are rarely seen in cancers and are more often seen in the noncancerous background mucosa [5]. Accordingly, the disappearance of regular LBCs is a useful marker in identifying the demarcation line (DL), the border between cancer and noncancer [6].

Furthermore, although LBCs are rarely detected in the tumor epithelium, their presence in LBC-positive tumors may be a useful indicator of the small intestinal type of intestinal metaplasia. We await the results of further systematic studies.

10.2 White Opaque Substance (WOS)

10.2.1 What Is WOS?

I have previously reported that the mucosal subepithelial microvascular pattern (V), as visualized using magnifying endoscopy, is a useful marker in distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions, and I use it in clinical practice. At the same time, I became aware that a WOS is present on the mucosal surface of some epithelial tumors, in particular superficial elevated lesions, decreasing the transparency of the mucosa and interfering with visualization of the mucosal subepithelial V. In these cases, magnified endoscopic evaluation of the V component is impossible, and according to the VS classification it is defined as an “absent MV pattern” and the interpretation is based on the S component alone.

10.2.2 Prevalence and Morphological Characteristics According to Histological Type of WOS in Superficial Elevated Epithelial Tumors

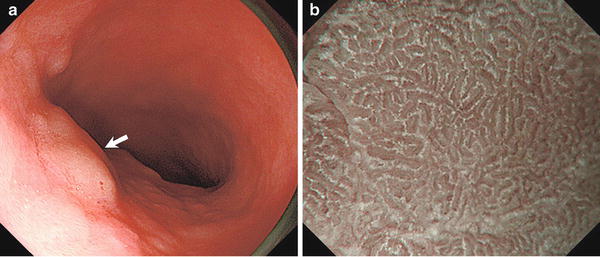

First, I analyzed the prevalence and type of WOS according to histological type in 46 superficial elevated epithelial tumors (Figs. 10.3–10.6). WOS was seen in both adenomas and carcinomas, with a prevalence of 78% and 43%, respectively, significantly more common in the former (p < 0.05) (Table 10.1). Furthermore, the WOS morphological characteristics were different in adenomas and carcinomas (Table 10.2).

Fig. 10.3

WOS (−). Non-magnifying endoscopy (a) and magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (NBI) images (b) of superficial elevated epithelial tumors. a Adenoma on the lesser curvature of the mid-gastric body (low-grade dysplasia: LGD). Arrow indicates lesions. b M-NBI clearly shows a regular MV pattern typical of an adenoma (reprinted from [8] by permission of Gastrointest Endosc)

Table 10.1

Presence of WOS according to histological type (adenoma vs carcinoma)

n | Present | Absent | |

|---|---|---|---|

Adenoma | 18 | 14 (78%) | 4 (22%) |

Carcinoma | 28 | 12 (43%) | 16 (57%) |

Table 10.2

Morphology of detected WOS according to histological type (adenoma vs carcinoma)

n | Regular | Irregular | |

|---|---|---|---|

Adenoma | 14 | 14 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

Carcinoma | 12 | 2 (17%) | 10 (83%) |

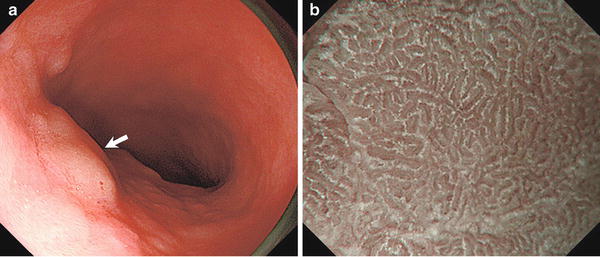

In effect, WOS was more prevalent in adenomas, and the morphology was generally coarse and more dense with a predominantly reticular, mazelike, or speckled morphology; a regular arrangement; and symmetrical distribution (regular WOS). On the other hand, in carcinomas, WOS was generally finer and less dense, with a reticular or speckled morphology, an irregular arrangement, and asymmetrical distribution (irregular WOS). I concluded that these morphological characteristics of WOS are useful in distinguishing between adenomas and carcinomas (Table 10.3).

Fig. 10.4

WOS (+). Regular WOS with mazelike pattern. Non-magnifying endoscopy (a) and magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (NBI) images (b) of superficial elevated epithelial tumors. a Adenoma on the lesser curvature of the gastric antrum (LGD). Arrow indicates lesions. b In contrast to Fig. 10.3b, the presence of WOS makes it impossible to discern the subepithelial V in intervening part (IP). Analysis of the WOS morphology shows it to be regular WOS with a mazelike pattern (reprinted from [8] by permission of Gastrointest Endosc)

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree