Fig. 16.1

Ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract. Reprinted with permission [3]. (a) Introduction of fistula probe through the tract. (b) Dissection of intersphincteric groove and identification of fibrotic fistula tract. (c) Suture ligation of fistula tract proximally and distally. (d) Additional ligature reinforcing tract closure. (e) Division of fistula tract; if tract is quite long, a segment of the tract is excised. (f) LIFT wound is closed loosely, and external opening of the tract is enlarged to facilitate drainage. LIFT ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract. Drawings courtesy of Russell K. Pearl, M.D. With permission from: Abcarian AM, Estrada JJ, Park J, et al. Ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract: early results of a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012 Jul;55(7):778–782 © Wolters Kluwer

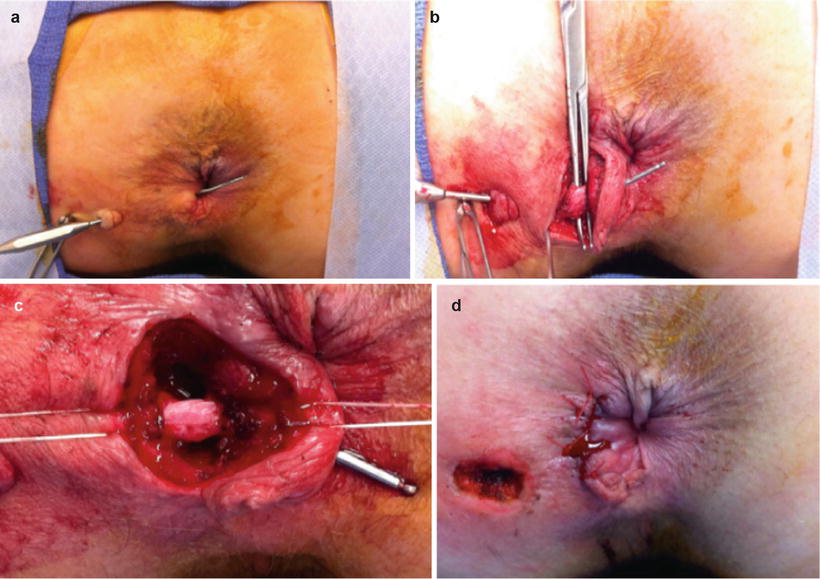

Fig. 16.2

Intraoperative photos of the original LIFT procedure, including our variation. (a) Passage of fistula probe through the transsphincteric tract. (b) Dissection to fibrotic fistula tract from surrounding muscle fibers. (c) Suture ligation of fistula tract proximally and distally. Probe should be removed prior to suture ligation. (d) LIFT wound closed loosely; external opening enlarged to facilitate drainage

Subtle variations of the original technique are described. We prefer to remove a portion of the tract if the length allows it [3]. The closure of the tract after suture ligation may be tested, either with direct probing or with injection of hydrogen peroxide or saline [2, 4, 5]. Postoperative admission for observation is not necessary. Several series report discharging patients with a week of oral antibiotics [2, 4, 5]. There is no consensus on the use of seton preoperatively. As a standard, at our institution, setons are used to drain all infection prior to undertaking definitive surgical repair of the fistula and many of the other series do so as well. There is anecdotal evidence that when the seton is left in place 8–12 weeks prior to LIFT, the tract fibroses nicely, making it easily identifiable and, in many cases, easier to dissect free from the surrounding tissues ensuring a successful ligation [3, 6]. Routine diagnostic imaging preoperatively or postoperatively with either MRI or endorectal ultrasound is not necessary. Diagnosis of fistula and treatment failures can be decided clinically.

This operation may be performed in prone jackknife or lithotomy position, under either regional or general anesthesia. Some surgeons use lithotomy or prone jackknife position depending on the location of the fistula [7]. Bowel preparation consists of two phospho soda enemas the day before surgery. Patients are administered only a single dose of appropriate peri-operative antibiotics intravenously, usually cefoxitin, or ciprofloxacin/metronidazole if the patient is penicillin-allergic. At the end of the procedure, a dibucaine-coated piece of gelfoam is rolled and gently inserted into the anal canal for analgesia. The patients are not admitted for observation and are sent home directly from the recovery unit on oral analgesics and stool softeners [3].

Results/Discussion

Rojanasakul’s initial LIFT series in 2007 was a prospective observational study of 18 patients with fistula in ano [1]. He reported 94.4 % (17/18) healing, and one non-healing at 4 weeks of follow-up. There was no reported incontinence [1]. These impressive results set the mark for LIFT to become a promising option in treating fistula in ano, particularly since the other available sphincter sparing options have variable success rates of 31–80 % at best [8–11]. Utilizing a new procedure that could offer >90 % success rate was exciting and many centers began to learn and perform the procedure, observing their results along the way.

The next published series came from Shanwani et al. [4], Bleier et al. [12], and Ooi et al. [13] which were collected prospectively as observational studies, and a retrospective review from Aboulian et al. [5]. These early reports suggested a healing rate of 57–82 % at 9–24 weeks follow-up, suggesting, as Rojanasakul had proposed, that larger series with longer term follow-up were needed to fully assess the success and limitations of the LIFT as a new surgical tool [4, 5, 12, 13]. In our series we reported overall healing of 74 % at 18 weeks with some preliminary data suggesting success rate of 90 % could be possible when LIFT was used as the first fistula procedure after seton placement [3]. Sileri et al. published a prospective study on 18 patients with complex fistulas. Following their LIFT procedure, they reported 83 % healing at median follow-up of 4 months [14].

Aboulian et al. recently published a longer follow-up of their initial cohort. Overall primary healing was reported at 61 %. They found that 80 % of failures were early, i.e., in the first 6 months following LIFT, and 20 % occurred after the first 6 months. One failure was reported at 12 months post-LIFT. No subjective incontinence was reported [15].

Wallin et al. published 93 patients and with an overall success rate of 40 % after initial LIFT at median of 19 months follow-up [16]. When including patients who underwent repeat (salvage) LIFT and/or intersphincteric fistulotomy, the success rates were 47 % and 57 %, respectively. Incontinence was observed and tracked using Wexner incontinence scores and patients with successful fistula healing were found to have a CCFFI score of 1.0 [16]. This study illustrates the desirable points of any novel sphincter sparing technique, i.e., reasonable success rates with good functional outcome and minimal risk of incontinence. Table 16.1 summarizes the published LIFT series to date.

Table 16.1

Summary of published LIFT series

Authors | Number of patients | Healing rate (success), % | Follow-up time | Measured continence scores Y/N | Type of study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rojanasakul et al. [1] | 18 | 94 | 4 weeks | N | Prospective |

Shanwani et al. [4] | 45 | 82 | 9 months | N | Prospective |

Bleier et al. [12] | 39 | 57 | 20 weeks | N | Prospective |

Aboulian et al. [5] | 25 | 68 | 24 weeks | N | Retrospective |

Sileri et al. [14] | 18 | 83 | 4 months | N | Prospective |

Ooi et al. [13] | 25 | 68 | 22 weeks | Y | Prospective |

Abcarian et al. [3] | 39 | 74 | 18 weeks | N | Prospective |

van Onkelen et al. [20]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|