Mature metacompartment

Building blocks

Primitive metacompartment

Developmental domains with fixed topological relations to each other

Mature ontogenetic compartments

Endopelvis

Endoderm

Cloaca and allantois

Primitive bladder

Bladder

Splanchnopleuric mesoderm

Internal UGS

Internal UGS compartmenta

Hindgut

Rectum and mesorectum

Ectopelvis

Ectoderm

Primitive pelvic walls and tail with sacral and coccygeal somites

Pelvic integumental primordium

Pelvic integument

Somatopleuric mesoderm

Paraxial mesoderm

Pelvic fascia, muscles and bones

Caudal eminence mesoderm

Pelvic fascio-musculo-skeletal blastema

Pelvic parietal peritoneum

Intermediate mesoderm

Pelvic coelom

Mesopelvis

Urogenital ridges with mesonephroi

Primordial gonads

Ovaries and mesovars

Paramesonephric-mesonephric complex

Müllerian compartmentb

Splanchnopleuric mesoderm

Pelvic ureters

Metanephric complex

Definitive UGMc

Somatopleuric mesoderm

Primordial UGM

Pelvic orifice

Ectoderm

Cloacal membrane and folds

External UGS

External UGS compartmentd

Endoderm

Extraembryonic mesoderm

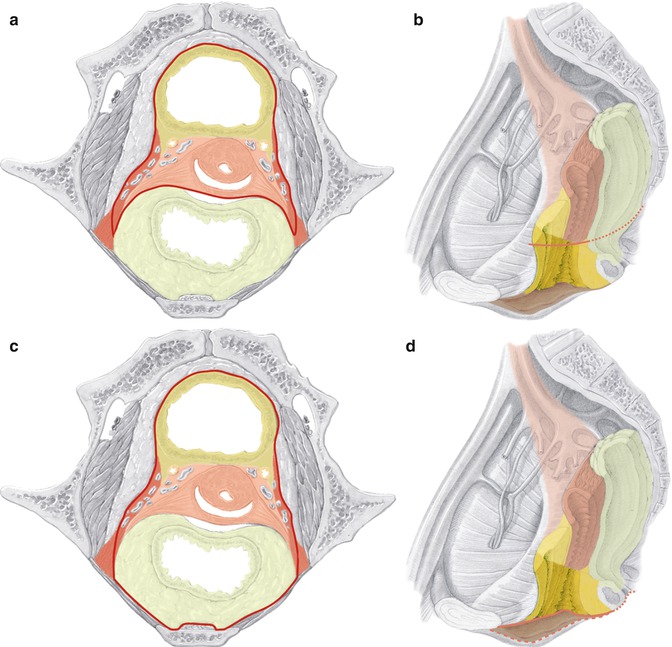

Fig. 37.1

Ontogenetic anatomic mapping of the adult female pelvis indicating developmental compartments. (a) Transverse section at the level indicated by the inset. (b) Midsagittal section with hollow organs transected transversely, visceral branches of the internal iliac vessels and lymph fatty tissue removed. Uncolored, ectopelvis; yellow, endopelvis; red, mesopelvis; brown, pelvic orifice (Modified from Höckel et al. [12])

The pelvic ground plan is laid down in the fourth developmental week through migration, proliferation and specific interaction of cell lineages from the three germ layers—endoderm, mesoderm, ectoderm—establishing four primitive pelvic metacompartments for which I suggest the terms endopelvis, mesopelvis, ectopelvis and pelvic orifice. Interaction of cell populations from different primitive metacompartments during the following embryonic development (weeks 5–8) results in the formation of distinct epithelial-mesenchyme complexes that finally occupy domains with invariable topographical relations to each other. These epithelial-mesenchyme complexes are spatially defined by robust boundaries which prevent the mixing with cells of adjacent domains during further differentiation and maturation. They represent developmental (ontogenetic) compartments with fixed determination acting as modules of development independent from each other. Generally, within each compartment various subcompartments are formed during later development.

Synchronous with the formation of the pelvic developmental compartments three networks for their support are established from central primordia: the pelvic vascular system from the dorsal aorta, the pelvic lymphatic system from the posterior cardinal veins and the pelvic nervous system from the spinal neural tube, the spinal neural crest and the neural cord derived from the caudal eminence. Each support system can be regarded as a metacompartment in itself, and support compartments can be defined as mature differentiation products of the corresponding regional primordia. As an example, the lymphatic system of the pelvis can be divided into distal mesenteric, iliac and inguinal lymph compartments [18]. The distal parts of the support system, e.g. the lymph capillaries, interact with their recipient compartments and adopt features specific for that particular tissue. The proximal parts are conduction structures which transit other compartments within defined corridors.

Differentiation of the pelvic compartments during the fetal period is gender specific.

The female endopelvic compartments, hindgut, bladder primordium and internal urogenital sinus (UGS), develop into the rectum with its mesorectum, the bladder, and the internal UGS compartment. The latter forms the urethra, distal vagina and distal rectovaginal septum as described in detail elsewhere [19]. Dorsally, the internal UGS compartment is attached to the anterior rectum and merges caudally with the external UGS compartment (see below).

The mesopelvic compartments bridge the ectopelvis and the endopelvis. The gonadal primordia, paramesonephric-mesonephric complex and the metanephric complex are bilaterally connected to the ectopelvis by the primitive urogenital mesentery. These primordia differentiate in the female pelvis into the ovaries with mesovars, Müllerian compartment, pelvic ureters and the definitive pelvic urogenital mesentery. The structurally complex Müllerian compartment is described in detail elsewhere [7, 8]. The ureters sprout from the distal mesonephric ducts at the site of the junction with the primitive bladder. The resulting short common nephric duct is then incorporated into the bladder primordium undergoing apoptosis and fusing the ureter orifice to the bladder epithelium. Further differentiation and growth of this bladder region produce the trigone and shift the ureterovesical junction ventralward [20]. The ureter tip interacts with the metanephric blastema forming the early kidney which ascends outside of the pelvis. Thus, in the mature pelvis only the pelvic ureter is left from the metanephric system. The mature pelvic urogenital mesentery derived from its primitive precursor consists of fibrofatty tissue providing the corridors for the ureter, the visceral branches of the internal iliac vessel system, the lymph collectors and eventually intercalated lymph nodes from the Müllerian, bladder and UGS compartments [18]. The urogenital mesentery also fixes these compartments to the ectopelvis with a “mesopelvic fascia” anteriorly and a structurally complex “mesopelvic suspensorium” posteriorly. Using the ureter as landmark the pelvic urogenital mesentery can be formally divided into a supraureteral peritoneal part and an infraureteral retroperitoneal part. Below the level of the obliterated umbilical artery the retroperitoneal part proceeds into the subperitoneal part. Inferolaterally, the subperitoneal urogenital mesentery is attached to the pubo- and iliococcygeus muscles anteriorly at the site of the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis and to the coccygeus muscles/sacrospinous ligament close to the sciatic spine posteriorly. Superolaterally, the subperitoneal urogenital mesentery abuts the internal iliac vessel system, the proximal sciatic nerve and sacral plexus. Medially, it is separated by the plexus hypogastricus inferior from the ligamentous mesometria and mesocolpia which are parts of the Müllerian and internal UGS compartments. The peritoneal part of the pelvic urogenital mesentery corresponds to the distal broad ligament.

The ectopelvic compartments are represented by the pelvic epidermis, dermis, hypodermis, fasciae and musculoskeletal structures as well as the parietal peritoneum. Of particular relevance is the ectopelvic origin of the dorsolateral perineal complex which differentiates into the “Dartos fat pads” and overlying dermis providing the bulk of the labia majora and into the striated muscles of the superficial and deep perineum. The dorsolateral perineal complex has to be distinguished from the external UGS compartment derived from the pelvic orifice metacompartment which provides all other morphological structures of the vulva as well as the gynecologic perineum and the ventral anal segment [21].

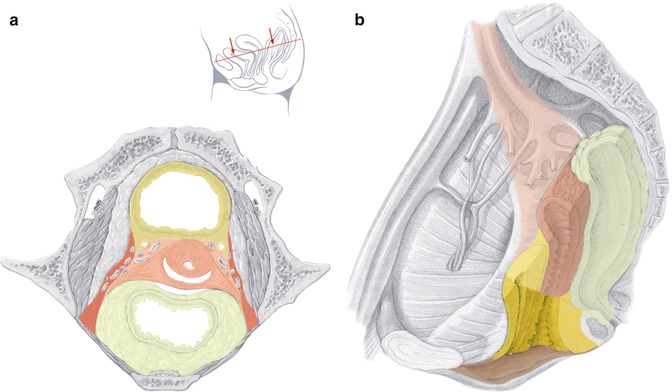

(Laterally) Extended Endopelvic Resection

Extended Endopelvic Resection based on ontogenetic anatomy aims to resect multiple pelvic developmental (ontogenetic) compartments instead of tissues related to functions, i.e. multiple pelvic viscera. The Müllerian compartment is resected en bloc with the bladder compartment and eventually with the hindgut compartment. Integrated into these multicompartment resections is the proximal part of the pelvic urogenital mesentery. The resection can be caudally expanded by including the internal and external UGS compartments. In the latter case the procedure has to be performed both from the abdominal and perineal routes, whereas otherwise solely the abdominal approach is adequate (Fig. 37.2).