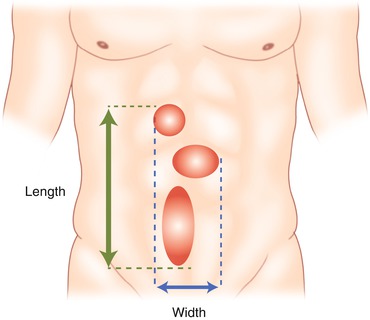

Fig. 9.1

EHS classification for primary abdominal wall hernias (Reproduced with permission from Muysoms et al. [5])

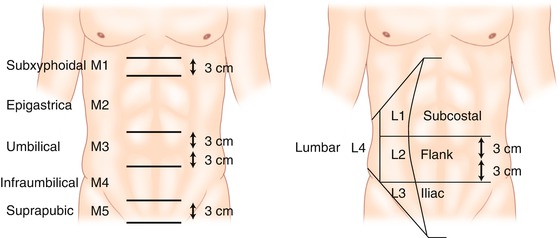

Fig. 9.2

Classification according to the location of incisional ventral hernias (Adapted with permission from Muysoms et al. [5])

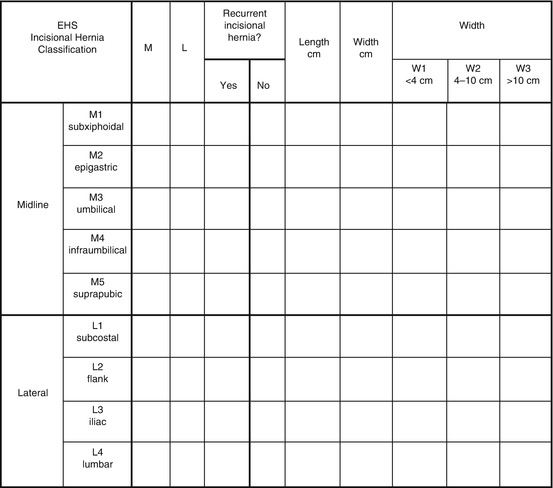

Fig. 9.3

EHS classification for incisional hernia classification (Reproduced with permission from Muysoms et al. [5])

In this chapter, we will focus only on midline ventral hernias.

Indications

The risk of developing, at any time during the hernia evolution, strangulation of the hernia content [6], damage of the skin that covers the hernia, or loss of home of the herniated intestine always makes it necessary to repair ventral hernia in adults by open or laparoscopic approach [7], avoided only in cases of absolute contraindications to the surgical procedure. There is no hernia measure that indicates or dismisses the laparoscopic approach to ventral hernia.

It is accepted that hernias under 3–4 cm can be repaired using conventional surgery and local anesthesia in an ambulatory setting [8]. Some authors establish 10 cm as the longest size in transversal diameter for laparoscopic repair, while others set this limit at 15 cm.

It seems to be reasonable that limits depend on the technical difficulties of handling the instruments and the mesh in the abdominal cavity [8, 9].

Surgical Technique

Technical variability between different surgical groups is essentially based on the mesh choice and the fixation method to the abdominal wall.

The common steps in the ventral hernia repair using a laparoscopic approach are as follows: patient positioning, pneumoperitoneum procedure, port placement, adhesiolysis, hernia content replaced inside the abdomen, and fixation of the mesh overlapping the hernia hole.

Patient Positioning

The patient is placed in a supine decubitus position, usually with arms fixed to the body. In obese patients, very often both arms are separated in order to allow better maneuverability of the instruments.

Pneumoperitoneum

Pneumoperitoneum technique will depend on the previous surgery performed on the patient and the surgeon’s suspicion of intraperitoneal adhesions to the abdominal wall. A Veress needle in the left hypochondrium is commonly used; previously a nasogastric tube was used in order to avoid a stomach puncture. In case of relevant adhesions, a port of vision is recommended.

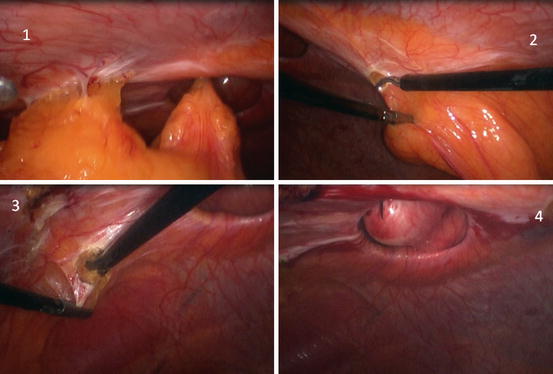

Adhesiolysis and Replacing Hernia Content (Fig. 9.5)

Fig. 9.5

Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. 1 ventral hernia, 2 section of round ligament, 3 section of umbilical ligament, 4 measure of the diameter of the hernia using a needle

Adhesions must be carefully managed with gentle traction maneuvers, using careful dissection whenever possible. Sharp dissection can be performed using an endoscopic scissor; avoid electric scalpels unless you are absolutely sure that there is not a hidden loop of intestine behind the adhesion.

Replacement of the hernia content is managed in a similar way. Exceptionally, external pressure maneuvers are needed to more easily replace the content into the abdominal cavity.

Placement and Fixation of Mesh (Fig. 9.6)

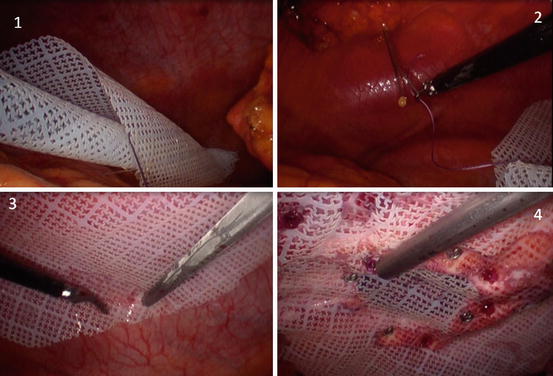

Fig. 9.6

Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. 1 rolled PTFE-c (Omira) mesh into the abdominal cavity, 2 cardinal points using a Reverdin (proxy) needle, 3 tackers in the outer crown, 4 tackers in the inner crown (absorbable tackers and nonabsorbable tackers, aiming for a lesser rate of pain and adherences)

A real measure of the hernia edge is needed, using an intramuscular needle inserted into the skin, in the four cardinal points of the hole. Mesh must exceed the size of the hernia hole by at least 3 cm; many authors today recommend a 5 cm mesh overlap.

In the next step, the mesh is rolled on its axis and introduced into the abdominal cavity through a 11 or 12 mm port or wrapped in sterile plastic to avoid contamination.

Double crown technique is generally used to place the mesh in the abdominal wall [12], fixed by absorbable or nonabsorbable tackers, preserving a distance of 1 cm between them, in both fixation lines, internal (edge) and external. Details and controversies will be discussed later in this chapter.

Complications

Complications can arise during the procedure or once it has been completed. In the sections that follow, we will describe the most common complications related to this procedure.

Intraoperative

These are usually related to the Veress needle puncture and the laparoscopic port placement. Adhesiolysis and hernia content replacement maneuvers may produce bowel perforation, hemorrhage, and visceral injuries [13].

Hemorrhage management includes, in addition to traditional methods, energy sources, sutures, clips, and hemostatic substances involving human thrombin.

Intestine perforation secondary to the treatment of ventral hernia is an added risk, both in open and laparoscopic surgery, with similar consequences [14]. One out of six of these patients will suffer this complication secondary to maneuvering dissection of adhesions, hernia content replacement, or first port placement. It can occasionally occur during the placement of the Veress needle.

An unnoticed intestinal perforation could become a serious threat to the life of the patient.

Postoperative

Postoperative complications related to surgical technique can be divided into minor complications (wound infection, seroma, hematoma, paralytic ileus, pain) and major complications (hemorrhage, prosthesis infection, sepsis, intestinal perforation, recurrence, and mortality).

A recent meta-analysis reported that wound infection in laparoscopic repair is lower compared to open surgery.

Seroma is the most prevalent complication of this surgery, and this still presents in almost 80 % of the cases, although it usually does not cause problems or any inconvenience to the patient. Recently, a classification of five types of seromas was developed (Table 9.1), ranging from the nonobvious clinical seroma to the seroma that needs treatment [15].

Table 9.1

Classification of seromas after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair

Type 0 | No clinical seroma | No clinical seroma | |

0a | Neither clinical nor radiological seroma | ||

0b | No clinical seroma, but it can be detected by radiological exams | ||

Type I | Clinical seroma lasting less than 1 month | Incident | |

Type II | Clinical seroma lasting more than 1 month: seromas with excessive duration | ||

IIa | Between 1 and 3 months | ||

IIb | Between 3 and 6 months | ||

Type III | Minor seroma related-complications: symptomatic seromas that may need medical treatment | Complication | |

IIIa | Clinical seroma lasting more than 6 months | ||

IIIb | Esthetic complaints of the patient due to seroma | ||

IIIc | Important discomfort which does not allow normal activity | ||

IIId | Pain | ||

IIIe | Superfitial infection with cellulitis | ||

Type IV | Mayor seroma related-complication: seromas that need to be treated | ||

IVa | Need to puncture the seroma to decrease symptoms | ||

IVb | Seroma drained spontaneously (applicable to open approach) | ||

IVc | Deep infection | ||

IVd | Recurrence related to seroma | ||

IVe

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |||