Laparoscopic Truncal Vagotomy with Antrectomy and Billroth I Reconstruction

Aurora D. Pryor

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Surgical management of peptic ulcer disease has metamorphosed with the advent of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy and elucidation of the role of Helicobacter pylori in gastric pathology. While gastric resections for ulcer disease were formerly a mainstay in the practice of general surgery, such procedures are now rare. Most patients are treated with 6 weeks of PPI therapy and eradication of H. pylori. This combination of therapies is effective in treating the majority of ulcers. However, indications do remain for surgical therapy for ulcer disease. The major indication is failure of medical management presenting as either intractable ulceration after a 3-month medical trial or issues such as perforation or bleeding while on therapy. Ulcers can also present acutely as a complication of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. Long-term complications of ulcers, such as gastric outlet obstruction or malignancy, remain reasons for surgery as well. An additional relative indication for surgery is a patient with complicated ulcer disease and poor access to care or unlikely follow-up.

The choice of surgical procedure is based on the indication. Simple Graham (omental) patch closure can be performed for pyloric channel or duodenal perforation. Vagotomy and pyloroplasty offers a definitive approach to a bleeding pyloric channel or duodenal ulcer. Wedge gastrectomy results in excision of perforated gastric ulcers, while providing adequate tissue to evaluate for underlying malignancy. Antrectomy, usually in conjunction with vagotomy, is most commonly used for patients with gastric outlet obstruction from chronic ulcer disease. Vagotomy and antrectomy can also be used for definitive management of a perforated pyloric channel ulcer in a stable patient with minimal soilage.

Vagotomy is performed to minimize acid production in patients undergoing surgery for peptic ulcer disease. It works by blocking acetylcholine-mediated acid release as well as preventing antral interneuron release of gastrin-releasing peptide which in turn stimulates antral G-cell gastric release. However, histamine and nonvagal-mediated gastrin release still occur following vagotomy. Truncal vagotomy gained popularity in the 1940s in the management of gastric acid production to limit ulcer formation. It was performed in conjunction with a drainage procedure to minimize complications of delayed gastric emptying that were witnessed in up to one-third of patients following vagotomy alone. Selective and highly selective vagotomy came into favor to maximize the benefits of diminished acid production without causing gastric dysmotility. With the success of PPI therapy, even these selective procedures have fallen out of favor. Most patients requiring surgery for ulcer disease today require either antrectomy for obstruction or duodenal access and therefore pyloroplasty closure. In these patients, concomitant truncal vagotomy can obviate the need for and expense of postoperative PPI with minimal added risk.

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are mesenchymal neoplasms originating from the cells of Cajal. Sixty percent of these tumors are found in the stomach. The diagnosis is suspected with any submucosal mass and confirmed in most cases with reactivity to KIT (CD117) and/or DOG1. Many GISTs are incidentally found, but some present as a source of bleeding due to rupture. The malignant potential increases with both size and mitotic index, with tumors <2 cm in diameter and with ≤5 mitoses per 50 HPF considered very low risk. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for localized GISTs amenable to resection.

Surgical resection for GISTs involves complete margin-negative resection with an intact pseudocapsule. Lymphadenectomy is not required. Although most of these lesions may be treated with wedge resection, occasionally antrectomy is required.

Pancreatic rests and adenomas may present preoperatively as suspected GISTs. Although they have low malignant potential, they are usually managed as if GISTs unless a benign diagnosis can be confirmed.

Carcinoids

Gastric neuroendocrine tumors are an unusual cause of gastric pathology. These lesions can be benign carcinoid tumors or neuroendocrine carcinomas. This determination can usually be made on the basis of hematoxylin- and eosin-stained biopsies. Some carcinoid lesions may be associated with atrophic gastritis, pernicious anemia, or elevated gastrin levels. Most small lesions confirmed to be benign can be removed with endoscopic or laparoscopic wedge techniques. Some advocate surveillance for benign lesions 10 to 20 mm or smaller. Many suggest that multifocal carcinoids should be resected with antrectomy. Neuroendocrine carcinomas should be managed with more radical resection, often total gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy.

Adenocarcinoma

Gastric adenocarcinoma is rarely confined to just the distal stomach in Europe or the Americas. The surgical approach is geared at obtaining an R0 resection, with negative margins and no evidence of residual disease whenever possible. In the United States and Europe, D1 lymphadenectomy involving just the perigastric nodes is standard. More extensive D2 lymphadenectomy adding nodal tissue surrounding the left gastric, splenic, and hepatic arteries as well as the celiac axis, although beneficial in Japan, has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality in Western trials. Removal of at least 15 lymph nodes is important for staging information.

Outcomes after laparoscopic versus open gastric resection are oncologically equivalent based on several studies in the setting of experienced laparoscopic surgeons and low-risk patients (ASA < 3). There are benefits with length of stay, resumption of oral intake, blood loss, and analgesia use as well.

On the basis of results of a landmark 2006 study by Cunningham and colleagues, patients with gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma should receive preoperative chemotherapy to improve progression-free and overall survival.

For patients with advanced disease, palliative resection, even involving total gastrectomy, has improved outcomes compared with surgical bypass. This includes both quality of life and possibly survival benefits.

Chronic ulcer disease patients require a trial of medical therapy prior to surgery. Most patients are expected to complete two 6-week courses of PPI therapy as well as eradication of H. pylori with proven failure. No specific bowel prep is required.

For patients with acute complications of ulcer disease, such as bleeding or perforation, preoperative resuscitation is important. These patients should have a urinary catheter placed. Blood or fluids should be given as necessary to assure adequate perfusion. In the setting of perforation, broad-spectrum antibiotics are also advised. A nasogastric tube may be placed to facilitate gastric decompression, but it should be removed before stapling.

Positioning

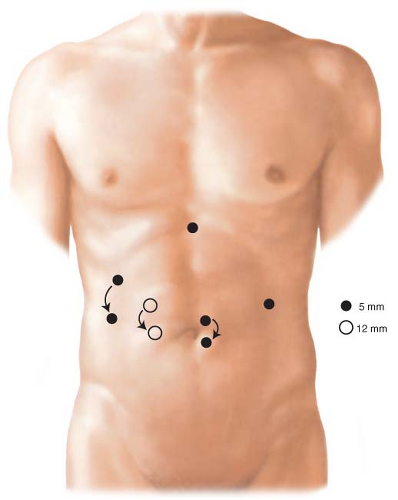

The setup for laparoscopic antrectomy in our practice has the patient placed supine with the arms extended out at the sides (Fig. 4.1). The surgeon stands at the patient’s right, with the assistant on the left. Monitors are placed over the patient’s shoulders.

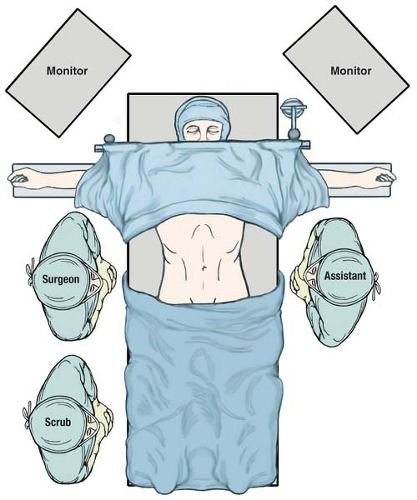

An endoscope should be readily available to help with identification of pathology or to test for leak at the completion of the procedure. Ports are placed to allow good access to the hiatus and distal stomach (Fig. 4.2). The procedure is performed in reverse Trendelenburg position. A liver retractor is helpful for proximal gastric and hiatal exposure. This is placed through a subxiphoid port.

An endoscope should be readily available to help with identification of pathology or to test for leak at the completion of the procedure. Ports are placed to allow good access to the hiatus and distal stomach (Fig. 4.2). The procedure is performed in reverse Trendelenburg position. A liver retractor is helpful for proximal gastric and hiatal exposure. This is placed through a subxiphoid port.

Figure 4.1 OR setup for laparoscopic gastrectomy. The patient is placed supine on the table with arms extended. The surgeon stands to the patient’s right and the assistant is on the left. |

Distal Gastrectomy

Distal gastrectomy may be performed for ulcer disease, benign lesions as well as cancer. If the resection is being performed for adenocarcinoma, the resection should include the greater omentum, duodenal bulb, and surrounding nodal tissue. The technical ease of antrectomy is greatly improved with modern vessel sealing technology. These devices can divide vessels up to 7 mm in diameter without requiring skeletonization or clips.

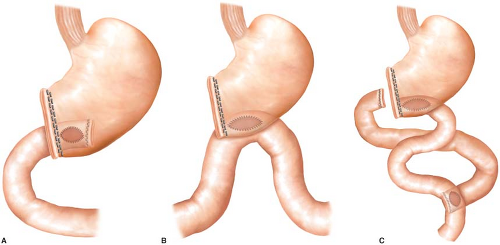

The variability of distal gastrectomy is greatly dependent on the planned reconstruction. The procedure can be completed with a gastroduodenostomy (Billroth I anastomosis), loop gastrojejunostomy (Billroth II anastomosis), or with Roux-en-Y reconstruction (Fig. 4.3). Billroth I reconstruction is the most anatomic and is preferred in our practice when technically possible. It also minimizes postoperative complications such as duodenal stump leak, afferent loop syndrome, and marginal ulceration. This approach will be the focus of this chapter. The anastomosis may be placed in a

variety of locations, but the distal posterior gastric wall is usually preferred to facilitate gastric emptying.

variety of locations, but the distal posterior gastric wall is usually preferred to facilitate gastric emptying.