Laparoscopic Total Gastrectomy and Esophagojejunostomy

Brant K. Oelschlager

Rebecca P. Petersen

Introduction

Over the past decade, minimally invasive surgery is being performed more frequently for the treatment of gastric cancer. As with other laparoscopic procedures, the intent of this approach is to reduce surgical morbidity while achieving similar cancer-free and overall survival rates as with conventional open surgical resection. The majority of studies comparing open and laparoscopic approaches for gastric cancer in regards to morbidity and oncologic efficacy have been for subtotal gastrectomies, mostly because it is technically easier to perform. More recently, however, laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) has become a more feasible approach for many surgeons. This is due to improvements in technology as well as advancing expertise with laparoscopic surgical technique. However, LTG is considerably more complex than partial gastrectomy and requires careful patient evaluation and planning to ensure that efficacy and safety are not being compromised compared to a standard open approach.

Background

Laparoscopic gastrectomy for the treatment of gastric cancer was initially described in the early 1990s, and early experiences were limited to partial gastrectomy. To date, the majority of studies have evaluated the outcomes of laparoscopic distal gastrectomies, and in general this has become an established approach for the treatment of limited gastric cancer. Early experiences with LTG were limited by technical difficulty in performing the esophagojejunostomy anastomosis and prolonged operative times compared with the open approach. As a result, LTG was not favored by even the most experienced minimally invasive surgeons. However, advances in stapling technology have enabled totally laparoscopic intracorporeal esophagojejunostomy anastomosis to be performed.

The first LTG was reported by Umaya and colleagues in 1999, where they performed a laparoscopy-assisted total gastrectomy with a distal pancreatosplenectomy and a D2

lymphadenectomy. In the same year, Azagra and colleagues also reported performing a minimally invasive total gastrectomy in 12 patients, but in the majority of these patients a laparoscopy-assisted approach was used. Now, there are several case studies which have demonstrated the feasibility of a “totally” LTG in experienced hands. While there has not been a controlled trial comparing LTG to open gastrectomy and it is not clear whether or to what degree there is a benefit over open resection, the benefit of a laparoscopic approach has appeal due to the broader experience with laparoscopic techniques. Importantly, LTG is a technically challenging operation; thus the surgeon must carefully and thoughtfully consider patient-specific details before performing these operations and be facile with laparoscopic techniques.

lymphadenectomy. In the same year, Azagra and colleagues also reported performing a minimally invasive total gastrectomy in 12 patients, but in the majority of these patients a laparoscopy-assisted approach was used. Now, there are several case studies which have demonstrated the feasibility of a “totally” LTG in experienced hands. While there has not been a controlled trial comparing LTG to open gastrectomy and it is not clear whether or to what degree there is a benefit over open resection, the benefit of a laparoscopic approach has appeal due to the broader experience with laparoscopic techniques. Importantly, LTG is a technically challenging operation; thus the surgeon must carefully and thoughtfully consider patient-specific details before performing these operations and be facile with laparoscopic techniques.

Patient Selection

Patient-specific selection criteria for LTG are not well established as there are very few studies and the majority of these are small case series evaluating only the technical feasibility of LTG. Therefore, until larger long-term outcome comparative trials are performed, patient selection criteria should be focused on general principles of minimally invasive surgery and should consider the technical challenges of the operation. As with any laparoscopic procedure, eligible patients should be without significant cardiac, pulmonary, or renal disease where prolonged pneumoperitoneum with carbon dioxide will not result in increased perioperative morbidity and/or mortality. Patients who have musculoskeletal or neurodegenerative disease and/or injuries which would preclude them from being placed in a modified lithotomy position in reverse Trendelenburg required to perform a LTG should be excluded as well. Multiple prior fore- or midgut operations is a relative contraindication to LTG and this is mainly practical since taking down adhesions from prior surgery can be time consuming and potentially risky (depending on the surgeon’s experience). Obesity is not necessarily a contraindication to TLG as these patients are likely to benefit in regard with decreased wound complications from a laparoscopic as compared to an open approach, but it is another factor that increases the technical difficulty of the procedure. LTG should only be attempted in conjunction with or by an experienced minimally invasive surgeon at a high-volume hospital given its overall technical complexity (Table 20.1).

Preoperative Evaluation, Treatment, and Procedure Selection

All gastric cancer patients should undergo a comprehensive preoperative evaluation which includes upper endoscopy, physical examination focusing on the abdomen and lymph nodes, appropriate noninvasive imaging to stage the tumor, assess size, and evaluate response to chemotherapy, and appropriate nutritional and cardiac screening (Table 20.2).

Table 20.1 Patient Selection Criteria | |

|---|---|

|

Table 20.2 Preoperative Assessment | |

|---|---|

|

The majority of patients with gastric cancer in the United States present with locally advanced disease, and as a result, the majority undergo multimodality therapy as outcomes have been shown to be superior to surgery alone for patients with stage II or III disease. In our center the most common regimen is perioperative chemotherapy before and after surgery as described in the MAGIC trial.

The type of gastric resection for the treatment of gastric cancer should be selected based on the anatomic site of the tumor, stage, histology, and prognostic factors. Therefore, all patients should undergo appropriate staging studies prior to considering surgical treatment. The first step is to perform an upper endoscopy with gastric biopsy to establish the diagnosis. Subsequently, a staging evaluation may include endoscopic ultrasound and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with or without a FDG–PET to determine the clinical stage. Some centers routinely perform staging laparoscopy as approximately 20% of patients with locally advanced tumors have peritoneal carcinomatosis.

The type of surgery should be based on the ability to achieve 5 cm gross surgical margins, clinical stage, and histology type. For patients with distal tumors, we recommend a subtotal gastrectomy. For patients with tumors located in the middle third of the stomach or in patients with infiltrative disease such as linitis plastica, we recommend a total gastrectomy and consider LTG. We also consider LTG for Siewert III gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) tumors when good esophageal margins are possible. However, most GEJ tumors (Siewert I-II) require esophagogastrectomy. Finally, the laparoscopic approach must not in any way compromise the type of gastric resection or lymph node dissection that is required.

The following is the approach used at the University of Washington.

Set-up and Patient Positioning

Operating Room Set-up

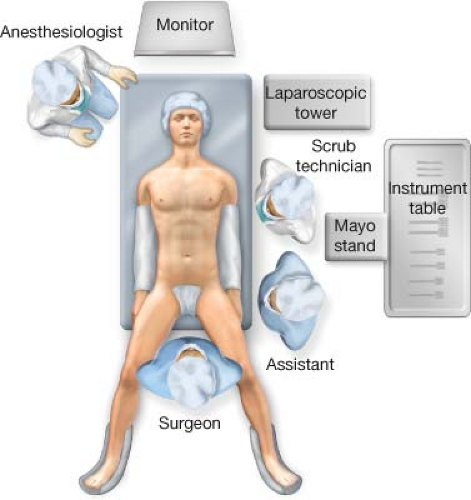

The laparoscopic tower is placed at the patient’s left shoulder or wherever facilitates placing the monitor over the head of the bed. At the beginning of the case, the surgeon operates by standing between the patients legs with an assistant at the left side of the operating room table (surgeon preference), as this facilitates the greater curve and esophageal mobilization. The scrub technician and Mayo stand are positioned above the assistant on the left side (Fig. 20.1). The patient is placed in a supine position prior to performing the Roux-en-Y reconstruction; at this point the surgeon and assistant move to the right and left side of the operating room table, respectively.

Patient Positioning

Following induction of general anesthesia after prophylactic antibiotics and heparin has been administered, the patient is initially placed in a low-lithotomy position on a bean bag which has been secured to the operating table to prevent the patient from slipping when placed in steep reverse Trendelenburg for the beginning of the operation. An alternative is a split leg table. This position allows the surgeon to comfortably stand facing the hiatus and use a left upper quadrant port for mobilizing the greater curve and especially the esophagus. Bilateral sequential compression devices are placed on the lower extremities and a Foley catheter with a temperature probe is placed for monitoring. Prior to the Roux-en-Y reconstruction, the patient is repositioned into a supine position (if desired) on the operating room table and taken out of steep reverse Trendelenburg to avoid nerve compression from long periods of time in stirrups.

Technique