Laparoscopic Resection of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors

R. Matthew Walsh

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) represent 1% of all primary gastrointestinal tumors and are the most common gastrointestinal tumor of mesenchymal origin. This group of neoplasms represents an interesting aspect of cell biology as an early example of a single gene mutation-induced neoplasm. The specific mutation occurs in the intracellular domain of the c-KIT proto-oncogene which is present in 80% to 95% of these neoplasms. This allows the neoplasms to be distinguished from leiomyomas of the stomach which are positive for desmin and negative for KIT.

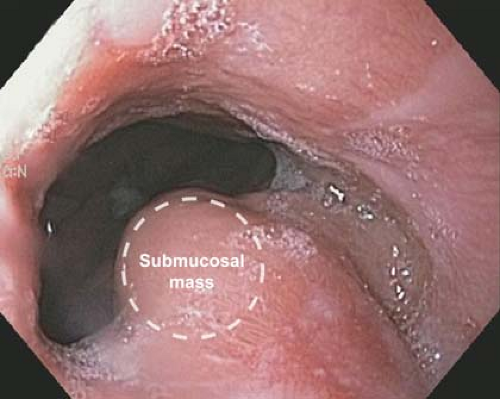

GISTs occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract but are most common in the stomach (50%) and small bowel (25%). They account for half of the submucosal lesions seen on upper endoscopy because they arise from the muscular layer of the intestine (Figs. 22.1 and 22.2). The median size at presentation is 5 cm and symptomatic patients in general present a decade earlier than asymptomatic patients with an overall median age of 66 to 69 years. The most common presenting symptom is gastrointestinal bleeding which occurs in one-third of patients and could be occult or overt bleeding. The next most common symptom is abdominal pain in 20% of patients. Additional presentations include an abdominal mass or incidental gastric mass on radiologic imaging or endoscopy. The presence of multiple GISTs can suggest familial GIST. The endoscopic view can include a well circumscribed submucosal mass that may include a deep ulceration for those presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding. And while this endoscopic finding is sufficient in symptomatic patients to proceed with resection, it is not specific.

Surgical resection is indicated for symptomatic GISTs, and biopsy is not required when tumor dissemination may be a risk. One tenet of treatment centers around the knowledge that all GISTs have malignant potential. Risk stratification is important to consider both for the indication for resection and for adjuvant therapy. Risk stratification for resection centers on size. Autopsy series demonstrate a high prevalence (22%) of small GISTs (<10 mm) in individuals over 50 years. Most of these small GISTs do not progress rapidly into large macroscopic tumors despite the presence of a KIT mutation. It is currently recommended that in acceptable risk patients, any GIST >2 cm should be resected. Contraindications to resection from a tumor biology perspective

include patients with known metastatic disease or unresectable tumor due to size or extended organ involvement that would lead to unacceptable morbidity or functional deficit. This latter group is amendable to neoadjuvant imatinib mesylate to downsize the tumor. This therapy typically lasts for 6 to 12 months with maximal response defined as no further improvement between two successive CT scans.

include patients with known metastatic disease or unresectable tumor due to size or extended organ involvement that would lead to unacceptable morbidity or functional deficit. This latter group is amendable to neoadjuvant imatinib mesylate to downsize the tumor. This therapy typically lasts for 6 to 12 months with maximal response defined as no further improvement between two successive CT scans.

A component of preoperative planning involves a consideration of the accuracy of the preoperative diagnosis for GIST. The differential diagnosis includes other submucosal masses such as lipoma, carcinoids, and leiomyomas or sarcomas, and nongastric masses which originate from the liver, pancreas, or spleen, as well as lymphoma or germ cell tumors. The diagnostic yield of endoscopy with biopsy is 35%, endoscopic ultrasound with fine needle aspiration (FNA) 84%, abdominal computed tomography 74%, and magnetic resonance imaging 91%. Endoscopic ultrasound is valuable in assessing the gastric layer from which the lesion arises as well as providing access for biopsy if that is required.

Once an accurate diagnosis of GIST has been determined, preoperative planning will be guided by size, location, and relative intra/extra gastric configuration. The interplay of all of these factors will determine the ultimate operative approach. A large lesion that is very exophytic or pedunculated on the anterior wall of the gastric body

is a straight-forward laparoscopic resection and would be an entirely different operative approach from the same size lesion of the posterior antrum with an appreciable intragastric component which may require a standard distal gastrectomy. A posterior location may extend into the retroperitoneum requiring a pancreatic resection for complete removal. Transgastric or intragastric procedures should be considered for posterior wall or gastroesophageal junction tumors with an intragastric component. A wide variety of minimally invasive techniques are appropriate for GIST tumors which defies the concept of a single best approach for all patients. The integration and assessment of intraoperative endoscopy by the surgeon and diagnostic laparoscopy should guide operative decisions regardless of the preoperative plan.

is a straight-forward laparoscopic resection and would be an entirely different operative approach from the same size lesion of the posterior antrum with an appreciable intragastric component which may require a standard distal gastrectomy. A posterior location may extend into the retroperitoneum requiring a pancreatic resection for complete removal. Transgastric or intragastric procedures should be considered for posterior wall or gastroesophageal junction tumors with an intragastric component. A wide variety of minimally invasive techniques are appropriate for GIST tumors which defies the concept of a single best approach for all patients. The integration and assessment of intraoperative endoscopy by the surgeon and diagnostic laparoscopy should guide operative decisions regardless of the preoperative plan.

Figure 22.2 Image obtained from endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). These tumors arise from the muscularis propria as demonstrated. They can have a dumbbell configuration which is not always evident on EUS. |

Preoperative planning does require consideration of special equipment for many laparoscopic resections. A video endoscope, angled laparoscope, specimen retrieval bags, and endoscopic linear staplers are standard fare. Intragastric procedures where the operation occurs in an insufflated stomach with intragastric ports is a special operation which should be planned. It behooves the surgeon to be prepared with the following equipment if an intragastric approach is being contemplated.

Endoscopy Equipment

Diluted epinephrine

Sclerotherapy needle

Over-tube

Biopsy forceps

Endo-snare

Roth-net

Laparoscopic Equipment

Balloon stabilized 5-mm trocars

Needle drivers

Ultrasonic shears

Hook cautery

Dual channel inputs for picture-in-picture

Robotic-assisted laparoscopy can also be performed for all manner of laparoscopic resections of GISTs including intragastric procedures. Use of robotic techniques will be determined by equipment availability and expertise.

Regardless of the specific operative approach, laparoscopic versus open, intragastric versus transgastric, formal resection versus wedge resection, the same surgical objective should be obtained: complete resection without tumor disruption. The principle goal of resection is obtaining macroscopically negative margins. The need to achieve microscopically negative margins is uncertain, since outcomes are likely determined by biologic tumor behavior and not the microscopic margin. The presence of a positive margin may be falsely interpreted based on specimen retraction, and re-excision is not advised for a microscopically positive only (R1) resection. Radical resection that would include lymphadenectomy is not required to ensure good outcomes, but a formal resection may be required based on size and location to achieve the best functional outcome. Extended resection should be done for contiguous organ involvement only to the degree that an RO or R1 resection is accomplished. A laparoscopic approach to resection is feasible, providing the same principles of traditional surgery are upheld: complete resection without tumor disruption. It was due to concern for tumor disruption by manipulation of the tumor that laparoscopy was initially discouraged, but its utility has been borne out in many series.

Positioning

Routine supine positioning is employed with video monitors at the head of the bed. Rarely will the monitors be at the feet if an intragastric resection is entertained for an antral lesion. Access to the mouth should be available for intraoperative endoscopy. Use of a split-leg bed is purely based on surgeon preference.

Technique

There are multiple techniques used for laparoscopic resection of gastric GISTs due to the varied locations of the lesions. It also points to the ingenuity of techniques fostered by minimal access surgery. General approaches will be discussed that are adaptable to specific situations.

Laparoscopic Wedge Resections

In this general scenario, wide access to the abdominal cavity is required with trocars positioned in a lazy “U” as used for most upper abdominal surgery (Fig. 22.3). This involves typically five trocars, all 5-mm except for a 12-mm at the umbilicus for endo-GIA stapler and extraction site. This approach is acceptable for all anterior wall masses of any location and many posterior wall lesions accessible via transgastric approach or via the lesser sac. There is a common misconception that a wedge resection requires elevating the lesion and its gastric wall attachment using a stapler to transect both walls of the stomach in a single firing (Fig. 22.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree