Chapter 15 Laparoscopic Radical Cholecystectomy

Operative indications

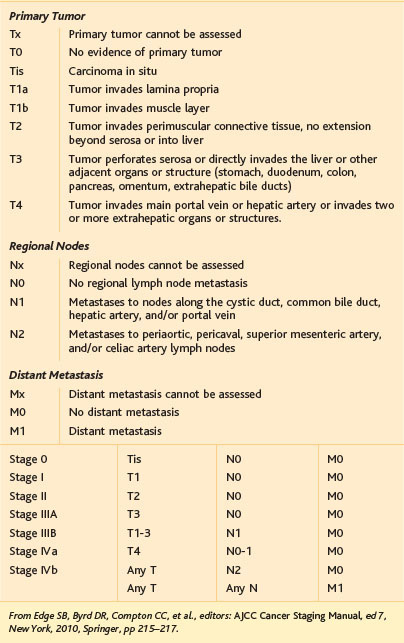

Operability in gallbladder cancer relies heavily on preoperative staging and considerations of findings during the initial laparoscopy or as part of a preoperative staging workup. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) in its seventh edition has established subcategories for stage IV gallbladder cancer. Stage IVA is defined by tumor invasion into the main portal vein, the hepatic artery, or two or more extrahepatic structures. The presence of metastases to the periaortic, pericaval, or superior mesenteric artery or celiac nodes or of distant metastases further defines stage IVB (Table 15-1). As mentioned previously, the extent of liver resection needs strong consideration and is controversial, with differing opinions regarding the suitability of nonanatomic resections of the gallbladder bed versus complete resection of segments IVB and V and even extended right hepatectomy (segments IV to VIII). We consider major hepatectomy or even extended hepatectomy only when this is necessary to achieve an R0 resection because there has been no conclusive difference noted in overall survival between minor and major hepatectomy.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>