Chapter 32 Laparoscopic Partial Nephrectomy

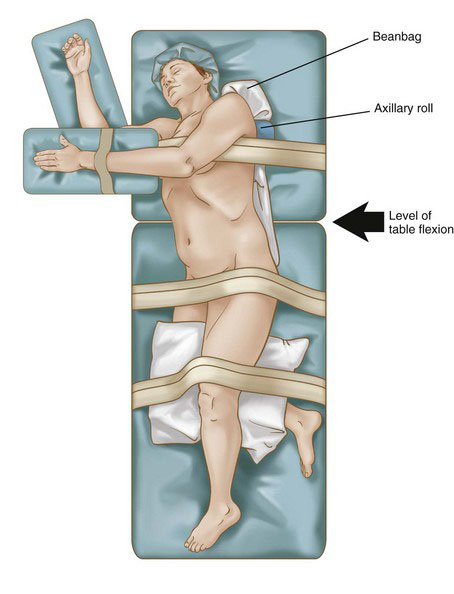

Patient positioning in the operating suite

The patient is placed in a modified lateral decubitus position using an underlying beanbag, with the thorax rotated back slightly at 30 degrees (Fig. 32-1). The lower hand is padded and placed on an armrest. The lower leg is flexed at the knee 90 degrees, and the upper leg is left extended. Pillows are placed between the legs for adequate support. Padding is placed under the lower ankle to relieve pressure in this area. An axillary roll then is placed 5 cm caudal to the axilla to protect the brachial plexus from a stretch injury. Additional padding is placed under the lower elbow to prevent ulnar nerve compression. The beanbag then is placed on vacuum to secure the final position. The umbilicus and spine should be visible to ensure adequate exposure in the rare need for an emergent open conversion. Surgical towels are placed over the skin at the hip and knee levels, and 3-inch silk tape is wrapped circumferentially at these levels to completely secure the patient to the table. Finally, an armrest is fastened to the table and secured to support the padded ipsilateral arm. Careful attention to final position and pressure padding is essential because bed rotation during surgery is often required to optimize exposure and assist with gravity bowel retraction. Care is taken not to obstruct any intravenous line.

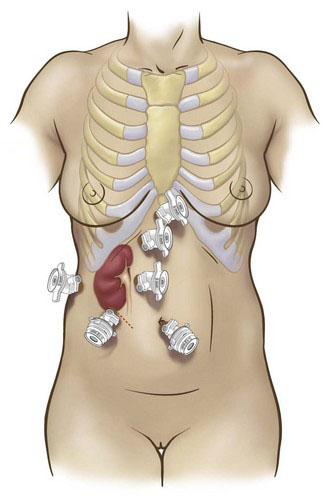

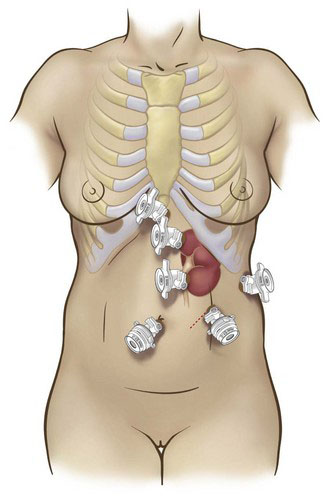

Positioning and placement of trocars

Transperitoneal access is our preferred approach to LPN, given the larger working space, familiar landmarks, greater versatility of instrument angles, and improved ease of suturing that this approach affords. The important anatomic landmarks for initial access are the subcostal margin, the umbilicus, and the rectus abdominis muscle. Standard port placements for right- and left-sided procedures are summarized in Figures 32-2 and 32-3 (four ports for left and five for right), respectively.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree